Module 3: A Willingness to Change

Module Overview

At the end of Module 2, you completed Planning Sheet 1 in which you chose a behavior you want to change. The success of any treatment plan hinges upon our dedication and strong desire to make the change. Without this, we will either fail at the plan or complete it and relapse in the future. To help us figure out how willing we are to make the change we will discuss the pros and cons of not changing the problem behavior or making the change, and self-efficacy. This will lead us to Planning Sheet 2.

Module Outline

- 3.1. Thinking About Changing

- 3.2. Pros and Cons of Making Change

- 3.3. Self-Efficacy

- 3.4. Planning Sheet 2: Pros and Cons of Changing or Not Changing the Behavior

Module Learning Outcomes

- Clarify stages people go through when deciding to bring about behavior change.

- State the utility of a pros and cons analysis.

- Clarify the role of self-efficacy in behavior change.

3.1. Thinking About Changing

Section Learning Objectives

- Outline the steps of change.

Prochaska, Norcross, and DiClemente (1995), in their book, Changing for Good, state that “Change is unavoidable, part of life. Few changes are under our control. But some things we can intentionally change.” How so? We must initiate change to help modify thoughts, feelings, or behaviors. They also say, “In change, timing is everything” and nine processes are involved. A few of interest are countering in which we substitute healthy responses for unhealthy ones, helping relationships or asking for help from your loved ones so you don’t have to go it alone, rewards or giving yourself a special prize when you achieve your goal and minimizing the use of punishment, commitment or accepting responsibility for the change on a personal level and then “announcing to others your firm commitment to change,” and conscious awareness or bringing unconscious motivations to a conscious level.

Knowing when to change is key as if you are not ready, you will inevitably fail. Likewise, if you spend too much time trying to understand your problem you might put off change indefinitely. Change unfolds through a series of six stages and successful self-changers follow the same road for each problem they desire to modify. These stages include: precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, maintenance, and termination. Let’s look closely at each.

3.1.1. Precontemplation Stage

This is when the person is not considering making a change and even resists the idea. Control of the problem is shifted to outside the person and he/she does not want to be nagged about the problem from family and friends. The individual even denies responsibility for the problem and justifies the behavior.

Prochaska, Norcross, and DiClemente (1995) suggest the individual answer the following questions to help them see the difference between problem behaviors and lifestyle choices:

- Do you discuss your behavior pattern?

- Are you well informed about your behavior?

- Are you willing to take responsibility for the consequence of your behavior?

Individuals move out of the precontemplative stage when they realize that their environment no longer supports their unhealthy lifestyle, when there is social pressure to make the change, or they receive direct requests from others such as employers.

3.1.2. Contemplation Stage

This is when change is seriously considered, but within the next six months. Many people stay stuck in this stage for a long period of time due to a fear of failure and so postpone and procrastinate. We have made the decision to change, but when the time is right. Of course, we all know there is no such time. We also engage in wishful thinking and desire to live as we always have but with different consequences such as eating what we want and not gaining any additional weight.

The authors state that you know you are ready to move on when your focus is on the solution and not the problem. We need to engage in consciousness-raising by asking the right questions such as understanding how many calories we really need to consume each day or what the effects of smoking are on the body and how long it will take to recover from them, if we can at all. We might also set goals, collect data, and do a functional assessment. In any case, it is critical to engage in this task during the contemplation stage as it helps us to be more aware of our problem behavior, “gain insight into how your thinking and feeling maintain the problem, and begin to develop a personal conviction of the value of change” (Prochaska, Norcross, and DiClemente, 1995).

You can even engage in a process of self-reevaluation, which if successful, will show that your fundamental values are in conflict with the problem behavior. We might assess how unhappy we are with the habit or behavior in the present, and then engage in an appraisal of our happier, healthier changed selves in the future. We could also think before we act especially with problems involving overeating, smoking, or drinking; create a new image of a changed you; and evaluate the pros and cons of changing, which we will discuss in Section 3.2.

3.1.3. Preparation Stage

This is when the person gets ready to change within the next month. Make your intention to change public and develop a firm, detailed plan for action. In terms of the plan, be specific about what steps you will take to solve the problem. Commitment involves a willingness to act and a “belief/faith in your ability to change” which we will discuss in Section 3.3. Engage in social support also at this time, even if you decide not to make your plan for change public.

3.1.4. Action Stage

Now fully committed to change, we enter the action stage. This requires a great deal of time, energy, and sacrifice; and we must be aware that the action stage is “not the first or last stop in the cycle of change.” The action stage lasts for months and involves being aware of potential pitfalls we may encounter. We discuss this in Module 11 in relation to temptations and mistakes.

It is during this stage we engage in the process of change called countering, or substituting a problem behavior with a healthy behavior. Of course, all we may do is substitute one problem behavior for another but to minimize that possibility, we could engage in active diversion by keeping busy or refocusing energy into an enjoyable, healthy, and incompatible activity. We might exercise, relax, counterthink by replacing troubling thoughts with more positive ones, or be assertive especially if others in your life are triggering the problem behavior. Though resisting temptation is an accomplishment, it is not reward enough, and so we need to be rewarded when we counter, exercise, relax, counterthink, or be assertive. Helping relationships are also important to make our success more likely. We will cover many strategies in Modules 6-9 so keep this discussion in the back of your mind until then.

3.1.5. Maintenance Stage

This is when change continues after the first goals have been achieved. To be successful, your change must last more than just a few days or months. It should last a lifetime. To be successful at maintenance Prochaska, Norcross, and DiClemente (1995) state that you should have long-term effort and a revised lifestyle. Relapse is a possibility if you are not strongly committed to your change.

How do you maintain your positive gains? Stay away from situations or environments that are tempting. Our former problems will still be attractive to us, especially in the case of addictive behaviors. What threatens us most are “social pressures, internal challenges, and special situations.” In terms of internal challenges, the authors state that these include overconfidence, daily temptation, and self-blame. Creating a new lifestyle is key too. If we are under a great deal of stress, exercise or practice relaxation techniques instead of engaging in our former behavior of comfort eating or drinking alcohol.

3.1.6. Termination Stage

This is when the ultimate goal has been achieved but relapse is still possible. Actually, Prochaska, Norcross, and DiClemente (1995) note that, “Recycle is probably a more accurate and compassionate term than relapses. Recycling gives us opportunities to learn.” How so? They note that people pass through the stages not in a linear fashion but more in a spiral. It may seem like we are not making progress, but the spiral is ever pushing upward. Also, few changers ever terminate the first time around unless they have professional help or a clear understanding of the process of change. The authors have several other key recommendations for avoiding relapse/recovery which we will cover in detail in Module 16.

See also: McConnaughy, DiClemente, Prochaska, and Velicer (1989) and Prochaska and DiClemente (1992)

So how do you know which stage you are in? Prochaska, Norcross, and DiClemente (1995) say to answer ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to the following four questions:

- I solved my problem more than six months ago.

- I have taken action on my problem within the past six months.

- I am intending to take action in the next month.

- I am intending to take action in the next six months.

Scoring:

- If you answered ‘No’ to all four questions – Precontemplation stage

- You answered ‘Yes’ to #4 and ‘No’ to 1-3 – Contemplation stage

- You answered ‘Yes’ to 3 and 4 and ‘No” to 1 and 2 – Preparation stage

- You answered ‘Yes’ to #2 and ‘No’ to #1 – Action stage

- You answered ‘Yes’ to #1 – Maintenance stage

What were your results? Is this surprising to you?

You will report this finding on Planning Sheet 2 under Question 6.

Now let’s discuss the stages of change Prochaska, Norcross, and DiClemente (1995) refer to on a deeper level. Of course, a slightly different framework will be used in this book, but as you will come to see, it largely reflects the process of change model these authors proposed over two decades ago.

3.2. Pros and Cons of Making Change

Section Learning Objectives

- Clarify the importance of weighing the pros and cons against one another.

- Apply pros and cons to your own attempt at behavior modification.

Thinking may come with the best of intentions but doing is what really counts. We know this as the cliché, ‘Action speaks louder than words.’ So how might you get to the action period? One technique is to weigh the pros and cons of any decisions involving the target behavior.

First, start by discussing the pros and cons of not changing the behavior. If we continue doing things exactly as we have so far, what would happen? Consider that we have engaged in the problem behavior (i.e. smoking, playing video games instead of studying, acting out) because it gives us some benefit. We will learn in Module 6 that these are called reinforcers and they continue the behavior. For our purposes now, they are the pros of not changing. But because they are a problem, they cause bad things to happen too. These are the cons. This discussion focuses on problem behaviors which are behavioral excesses. What about deficits? We do not engage in the desirable behavior because some other behavior is more attractive or we just have not motivated ourselves enough to do so. There are also cons for leaving the behavior as is and pros of changing it.

Once we have dealt with not changing the behavior, we need to move to the pros and cons of changing the behavior. This discussion should be addressed in a short-term, long-term fashion. In either case, good things (pros) will come from making the change but there are negatives ramifications as well (cons). Some of these will happen right away or in a very short term while others may take years to occur.

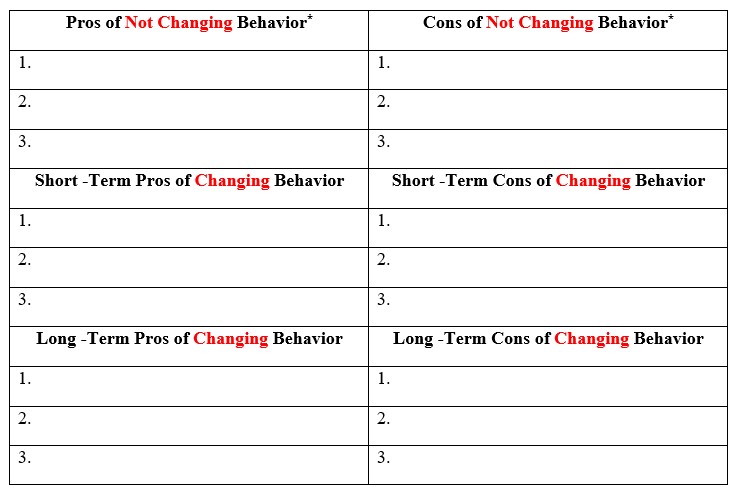

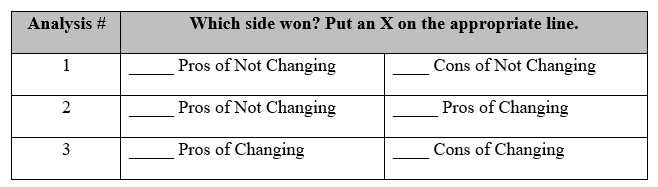

Use the following table when addressing your pros and cons. Notice that there are three spots under each category to list the pros or cons. You could conceivably list far more than three for some, but also less than three for others. It all depends on your target behavior. Do research. There is nothing wrong with finding reasons you might not be aware of for changing your behavior or the consequences of not changing. Type or write them into Planning Sheet 2 (found in Appendix 1) and add rows as needed.

Table 3.1. Pros and Cons of Not Changing and Changing Behavior

* To be clear, for not changing, you are asking yourself the following:

- Pros – What is good about keeping things as they are now?

- Cons – What is bad about keeping things as they are now?

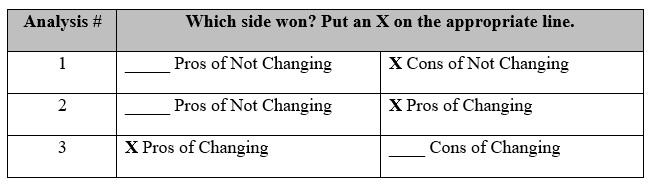

Changing our behavior benefits us, but likely comes at a cost. The key question is whether the benefits outweigh the costs. So, it is a good idea to not only make your list, but to analyze it too. To do this, use the following three analyses:

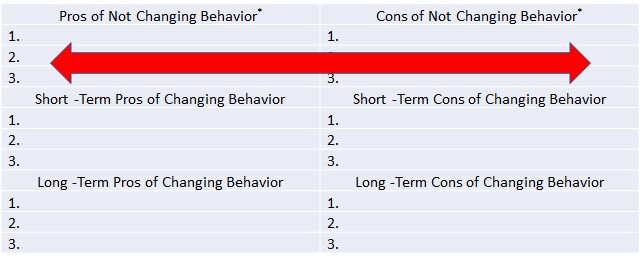

- Weigh the pros of not changing against the cons of not changing. Ideally, the cons outweigh the pros opening the door for change. Be clear that you understand what this means. Consider the target behavior of adding exercise to your daily routine which means you do not work out now, or do so very little. The pros of not changing have you consider what the benefits of not working out are for you. The cons consider what is bad about not working out for you. The direction of analysis will look like the following:

Figure 3.1. Analysis 1 – Pros of Not Changing vs. the Cons of Not Changing Behavior

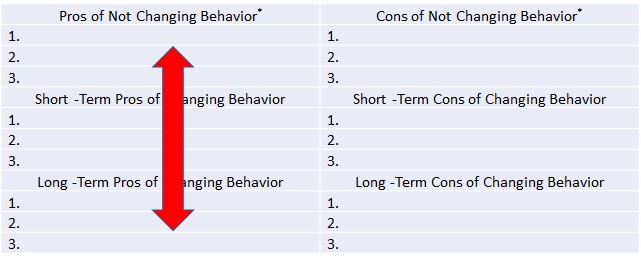

- Weigh the pros of not changing against the short and long-term pros of changing the behavior. Ideally, the pros of change win out. In our example, compare what is good about not working out versus what is good about working out. The direction of analysis will look like the following:

Figure 3.2. Analysis 2 – Pros of Not Changing vs. Pros of Changing Behavior

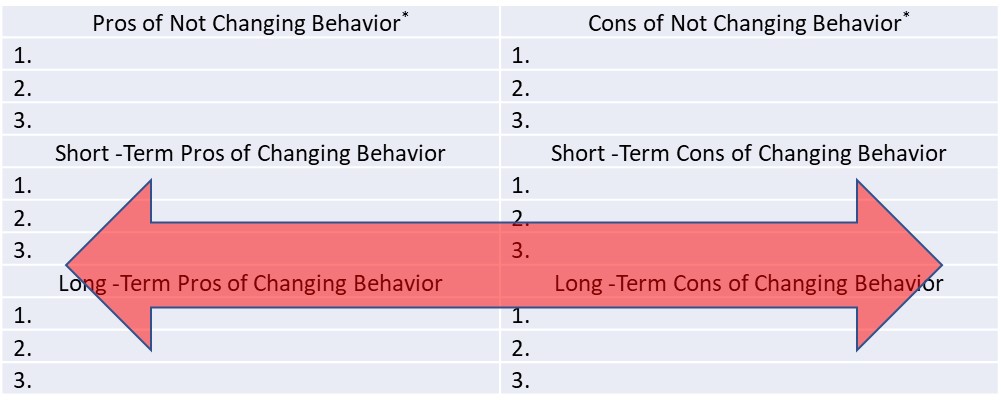

- Weigh the short and long-term pros of changing against the cons of changing. Again, the pros will hopefully win out. With our example, we are concerned about the benefits of working out versus the drawbacks of working out. The direction of analysis will look like the following:

Figure 3.3. Analysis 3 – Pros for Changing vs. Cons of Changing Behavior

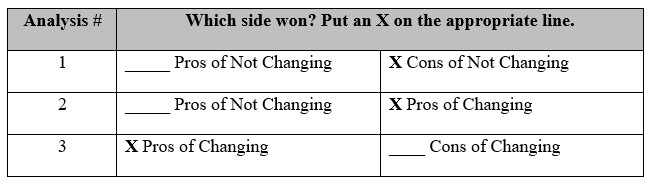

When doing the total analysis, one of three outcomes will occur. Use Table 3.2 to help you figure out which outcome is the correct one.

Table 3.2. Determining the Outcome of Your Total Analysis

- The cons of changing outweigh the pros of changing (Analysis 3) and/or the pros of not changing are greater than the pros of changing (Analysis 2) – In this case, you will remain in the precontemplative stage and not consider making any change.

- The pros and cons are even (for both not changing and changing; Analyses 1 and 3). In this case, you will likely stay in the precontemplative or contemplative stages. You might even flirt with the preparation stage.

- The pros of changing outweigh the cons of changing (Analysis 3) or the pros of not changing (Analysis 2) – In this case you might move to the action stage, and later maintenance and termination.

NOTE: It is important that you understand that this is not a mere numbers game. Having three items under pros and three under cons does not mean that the outcome of a particular analysis yields what is described in #2 above. Also, having 10 cons and 2 pros does not mean that cons win out. You are asked to do the analyses and then in your planning sheet, to interpret these analyses so that you can weigh each of the pros and cons you come up with. It may be that the cons, though greater in number, are really minor points, and the smaller number of pros have much more merit and weight. As such, pros win out and cons lose (or cons win out over pros for the not changing analysis). Make sure you understand this before going on.

Let’s tackle a few examples.

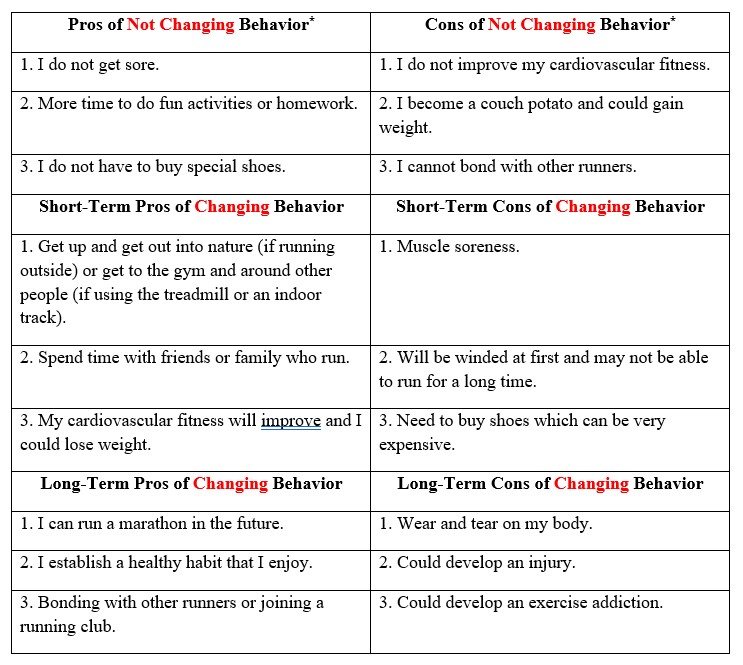

Example 1: Target Behavior – Running (Behavioral Deficit)

Exercise and its benefits seem obvious. Right? Exercise helps us with weight management, boosts energy, combats some diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease, builds our self-esteem, improves body image, makes our skin look better, and helps us recover from a major illness. But did you know that it also improves our mood, helps us manage stress, helps us sleep better, lifts depression, may make us age slower, can spark our sex life, and can be fun and help us to socialize with friends? Of course, exercise is not cheap if you choose to go to a gym or athletic club, but you can also exercise for free by just walking outside every day. So let’s examine the pros and cons of exercising more closely.

Table 3.3. Pros and Cons of Not Changing and Changing Running Behavior

Analyses:

- 1 – Pros of not changing against the cons of not changing – I can save money on shoes and can stay limber, but of course, I am not getting in shape and losing unnecessary weight.

- 2 – Pros of not changing against the short and long-term pros of changing – Though I am not sore I will never be in shape and cannot take finishing a marathon off my bucket list. The time I spend running, which does take away from homework (or video games) is well-spent.

- 3 – Short and long-term pros of changing against the cons of changing – Though shoes do cost a lot, they will help me with correct posture and protect my feet and back when running. I also get to spend time with my significant other who loves to run. And my bestie does too. I just need to protect against injury and addictive behavior.

- Total – All-in-all, running is better than not running. How do we know this? Take a look at the table below and compare it to the outcome descriptions above.

Table 3.4. Determining the Outcome of Your Total Analysis – Running Behavior

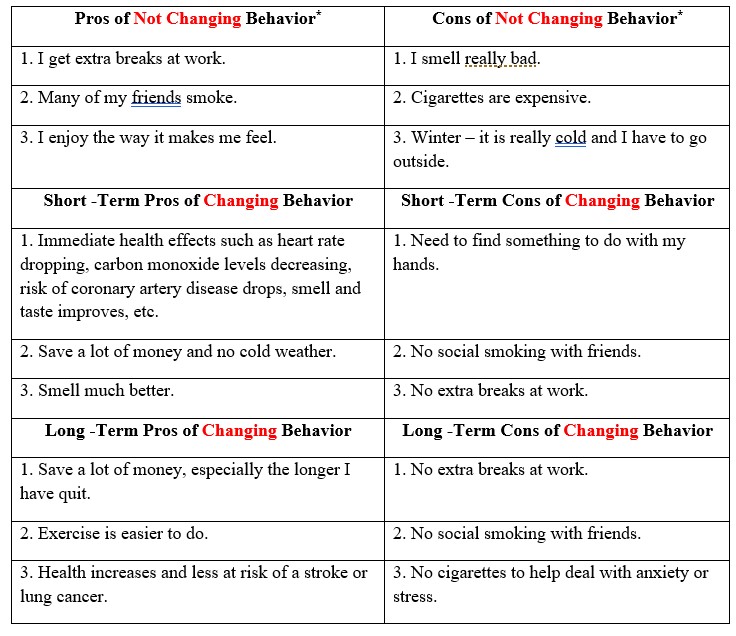

Example 2: Target Behavior – Quitting Smoking (Behavioral Excess)

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in 2011, nearly 7 in 10 adult cigarette smokers wanted to quit smoking. Four in 10 or 42.7% made an attempt within the past year. The CDC also points out that in fiscal year 2017, states will collect an astounding $26.6 billion from tobacco taxes and legal settlements. Of this only $491.6 million, or less than 2%, will be spent on prevention and cessation programs. Only Alaska and North Dakota fund these programs at the CDC’s recommended level while Oklahoma provides only half the recommended funding. Connecticut and New Jersey provide no funding. They write, “Spending less than 13% (i.e., $3.3 billion) of the $26.6 billion would fund every state tobacco control program at CDC-recommended levels.” Each day, an estimated 3,200 minors (under the age of 18) smoke their first cigarette and 2,100 occasional youth and young adult smokers become daily smokers. What’s at risk? Smoking leads to cancer, heart disease, emphysema, tuberculosis, rheumatoid arthritis, lung diseases, diabetes, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). (Source: https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/fast_facts/). So there is a definite need for smokers to kick the habit. Let’s examine the pros and cons more closely.

Table 3.5. Pros and Cons of Not Changing and Changing Smoking Behavior

Analyses:

- 1 – Pros of not changing against the cons of not changing – The extra breaks and support from my friends is good, but my significant other does not like the way I smell and I always have to try and hide the scent with perfumes or body sprays. The cost of cigarettes is really tough since I am a college student.

- 2 – Pros of not changing against the pros of changing – Though I get some social benefits, I prefer to live a full life. And the treadmill kills me.

- 3 –Pros of changing against the cons of changing – Saving money, living longer, and smelling better definitely outweigh the trivial social benefits. And hey, there is always gum and stress balls to keep my mouth and hand busy.

- Total – All in all, quitting smoking is better than continuing to smoke. How do we know this? Take a look at the table below and compare it to the outcome descriptions above.

Table 3.6. Determining the Outcome of Your Total Analysis – Cigarette Smoking Behavior

Bear in mind, that even with all the right reasons, a person may still not engage in change. They might stay in the contemplation or preparation periods and not move to the action period. Also, the road to change is long and hard and the person will likely relapse along the way before making lasting change (Prochaska and DiClemente, 1992). This is why patience truly is a virtue and persistence is needed.

Prochaska, Norcross, and DiClemente (1995) state, “Preparation for change lies in the balance between your perception of the pros and cons of changing. In the precontemplation stage, you are likely to perceive the cons of changing as outweighing the pros. You will need to increase your pros of changing twice as much as you need to decrease the cons. The Processes of Change applied in the early stages have the greatest impact on the pros. The Processes of Change applied in the preparation and action stages have the greatest impact on the cons.” Think about what these last two sentences mean before moving on. Take a look at the information on the six states again if you need to.

3.3. Self-Efficacy

Section Learning Objectives

- Define self-efficacy.

- Contrast those high and low in self-efficacy.

- Clarify how self-efficacy affects the success of a behavior modification plan.

Change is not easy and the more change we have to make, the more difficult or stressful. This is where Albert Bandura’s concept of self-efficacy (Bandura, 1982, 1986, 1991a, 199b) comes in.

Self-efficacy is our sense of self-esteem and competence and feeling like we can deal with life’s problems.

Self-efficacy includes our beliefs about our ability to complete a task and affects how we think, feel, and motivate ourselves. When our self-efficacy is high, we feel like we can cope with life events and overcome obstacles. Difficult tasks are seen as challenges and we set challenging goals. In contrast, if it is low, we feel hopeless, helpless, and that we cannot handle what life throws at us. We avoid difficult tasks and throw in the towel quickly when things get tough. These individuals are easily depressed and stressed.

Consider this in relation to how successful we might be with achieving our goal of changing an unwanted behavior or establishing a positive behavior. The pros and cons of changing the behavior, if weighing heavier on the side of making a change, give us the motivation or desire to make a change. But having the desire does not mean that change will occur. We have to have the ability also and possibly more important, we have to believe we can make the change. The change itself is the obstacle to overcome and is challenging for us. If it was not, we would have made the change already. Those high in self-efficacy will be more likely to move from the action stage to maintenance and termination of the treatment plan compared to those low in self-efficacy.

An example will hopefully help you to understand the relationship between willingness and ability. In terms of losing weight, many people genuinely desire to shed unwanted pounds. So they have engaged in a pros and cons analysis and the pros won out. But many do not understand how to lose weight in terms of making sense of caloric intake, the impact of specific foods they eat, consumption of sugars and protein, the role of sleep and water intake, etc. Armed with this knowledge they can be successful. Their ability would match their desire to make change. But many do not know these important facts and so lose some weight early on but then stagnate and give up. Losing the pounds is motivational or reinforces the weight reduction behaviors being used, leading to continued commitment to the plan. But when weight loss stagnates, we become frustrated and return to the behaviors that caused the problem in the first place.

On Planning Sheet 2, Question 7, you will rate your self-efficacy on a scale of 1-10 with 10 being the highest and 1 being the lowest. Answer honestly and really think about what your number means. How might you alter your self-efficacy if low? Maybe you can implement specific strategies to raise your motivation and likelihood of success. More on this later when we start to develop our treatment plan.

3.4. Planning Sheet 2: Pros and Cons of Changing or Not Changing the Behavior

Section Learning Objectives

- Complete and submit Planning Sheet 2.

Okay, so it’s time to apply what you learned to your self-modification project. Question 1 will ask you to list the pros and cons of not changing the behavior (keeping things the same) and then do the same for changing the behavior but looking at the short and long term effects. Then analyze these pros and cons and address your self-efficacy. Be sure you have read and understand the content before proceeding with this activity.

Planning Sheet 2 can be found in Appendix 1: Self-Management Plan Documents, at the back of this book.

Module Recap

In Module 3, we discussed a willingness to change from the perspective of DiClimente’s process of change and an analysis of the pros and cons of changing or staying the same. We also discussed self-efficacy and how believing in ourselves will make success more likely. Of course, success is never guaranteed, and everyone makes mistakes or gives in to temptation. These lost battles do not mean the war is lost though.

In Module 4, we will continue our discussion of planning for change by taking our target behavior and giving it a precise definition. We will also discuss the importance of goal setting and challenges with doing so.

STOP – Complete and submit Planning Sheet 2 –

See Appendix 1 to obtain it.