Unit 9: Using Source Text: Quoting, Paraphrasing, and Summarizing

Learning Objectives

After studying this unit, you will be able to

-

-

- quote source text directly with accuracy and correct punctuation

- paraphrase, summarize and reformat information collected from written materials

-

Introduction

Once you have a collection of credible sources as part of a formal secondary research project such as a report, your next step is to build that report using those sources as evidence. When you incorporate outside research into your writing, you must cite that information to ensure the reader knows what information is based on research sources. As with other areas of business writing, incorporate information from print or digital research into usable evidence takes skill and practice.

You essentially have four ways of using research material:

- Quoting text: copying the source’s exact words and marking them off with quotation marks

- Paraphrasing text: representing the source’s ideas in your own words (without quotation marks)

- Summarizing text: representing the source’s main ideas in your own words (without quotation marks)

- Reproducing media: embedding pictures, videos, audio, graphic elements, etc. into your document

In each case, acknowledging your source with a citation at the point of use and following-up with bibliographical reference at the end of your document is essential to avoid a charge of plagiarism. The following video provides a few tips on the why, where, and when of good citation practice.

Let’s now look at each of these research strategies in turn.

Research Strategies

Quoting Sources

Quoting is the easiest way to use sources in a research document, but it also requires care in using it properly so that you don’t accidentally plagiarize, misquote, or overquote. At its simplest, quoting takes word-for-word information from an original source, puts quotation marks (“ ”) around that information, and embeds it into your writing. The following points represent conventions and best practices when quoting:

- Use double quotation marks: In North America, we set off quoted words from our own words with double quotation marks (“ ”).

- Use a signal phrase to integrate a quotation: Frame a quotation with a “signal phrase” that identifies the source author or speaker by name and/or role, along with a verb relating to how the quotation was delivered. The signal phrase can precede, follow, or even split the quotation, and you can choose from a variety of available signal phrase expressions suitable for your purposes (Hacker, 2006, p. 603):

- According to researchers Tblisky and Darion (2003), “. . .”

- As Vice President of Operations Rhonda Rendell has noted, “. . .”

- John Rucker, the first responder who pulled Mr. Warren from the wreckage, said that “. . .”

- Spokespersons Gloria and Tom Grady clarified the new regulations: “. . .”

- “. . . ,” confirmed the minister responsible for the initiative.

- “. . . ,” writes Eva Hess, “. . .”

- Quote purposefully: Quote only when the original wording is important. When we quote famous thinkers like Albert Einstein or Marshall McLuhan, we use their exact words because no one could say it better or more interesting than they did. Also, quote when you want your audience to see wording exactly as it appeared in the source text or as it was said in speech so that they can be sure that you’re not distorting the words as you might if you paraphrased instead. But if there’s nothing special about the original wording, then you’re better to paraphrase properly (see paraphrasing sources below) than to quote and to source that paraphrase.

- Block-quote sparingly if at all: In rare circumstances, you may want to quote a few sentences or even a paragraph at length if it’s important to represent every single word. If so, the convention is to tab the passage in on the left margin, not use quotation marks, set up the quotation with a signal phrase or sentence ending with a colon, and place the in-text citation following the final period of the block quotation.

- Don’t overquote: As the above source says, a good rule of thumb is that your completed document should contain no more than 10% quoted material. Using more quotes will suggest that you’re using quotations to write your document. Quote no more than a sentence or two at a time if you quote at all.

- Quote accurately: Don’t misquote by editing the source text on purpose or fouling up a transcription accidentally. Quotation requires the exact transcription of the source text, which means writing the same words in the same order in your document as you found them in the original.

- Use brackets and ellipses to indicate edits to quotations: If you need to edit a quotation to be grammatically consistent with your own sentences framing the quotation (e.g., so that the tense is consistently past-tense if it is present-tense in the source text), add clarifying words, or delete words, do so using brackets for changed words and ellipses for deleted words. For more on quotations, consult How to Use Quotation Marks page and complete the online quiz.

Paraphrasing Sources

Paraphrasing or “indirect quotation” is putting research information in your own words. Paraphrasing is the preferred way of using a source when the original wording isn’t important. This way, you can incorporate the ideas and tailor the wording so it is consistent with your writing style and your audience’s needs. Also, paraphrasing a source into your own words proves your advanced understanding of the research information.

Only paraphrase short passages and ensure the paraphrase faithfully represent the source text by containing the same meaning as in the original source in about the same length. Remember, a paraphrase is as much a fact as a direct quotation. Therefore, your paraphrase must accurately reflect the information in the original text. As a matter of good writing, you should try to streamline your paraphrase so that it tallies fewer words than the original passage while still preserving the original meaning. In addition, a paraphrase must always be introduced. Since a paraphrase does not have visual cues to separate it from your writing, the reader must know when the paraphrase begins, for example with the phrase, “according to the author” and where the paraphrase ends, for example with a citation of the source.

For example: According to the author, paraphrasing can be challenging (author, year).

Properly paraphrasing without distorting, slanting, adding to, or deleting ideas from the source passage takes skill. The stylistic versatility required to paraphrase can be especially challenging to students whose general writing skills are still developing. A common mistake that students make when paraphrasing is to go only partway towards paraphrasing by substituting major words (nouns, verbs, and adjectives) here and there while leaving the source passage’s basic sentence structure intact. This inevitably leaves strings of words from the original untouched in the “paraphrased” version, which is considered plagiarism. Consider, for instance, the following botched attempt at a paraphrase of the Lester (1976) passage that substitutes words selectively (lazily):

Students often overuse quotations when taking notes, and thus overuse them in research reports. About 10% of your final paper should be a direct quotation. You should thus attempt to reduce the exact copying of source materials while note-taking (pp. 46-47).

Let’s look at the same attempt, but colour the unchanged words red to see how unsuccessful the paraphraser was in rephrasing the original in their own words (given in black):

Students often overuse quotations when taking notes, and thus overuse them in research reports. About 10% of your final paper should be direct quotation. You should thus attempt to reduce the exact copying of source materials while note taking (pp. 46-47).

As you can see, several strings of words from the original are left untouched because the writer didn’t change the sentence structure of the original. The Originality Report from plagiarism-catching software such as Turnitin would indicate that the passage is 64% plagiarized because it retains 25 of the original words (out of 39 in this “paraphrase”) but without quotation marks around them. Correcting this by simply adding quotation marks around passages like “when taking notes, and” would be unacceptable because those words aren’t important enough on their own to warrant direct quotation. The fix would just be to paraphrase more thoroughly by altering the words and the sentence structure, as shown in the paraphrase a few paragraphs above. But how do you go about doing this?

Paraphrase easily by breaking down the task into these seven steps:

- Read and re-read the source-text passage so that you thoroughly understand each point it makes. If it’s a long passage, you might want to break it up into digestible chunks. If you’re unsure of the meaning of any of the words, look them up in a dictionary; you can even just type the word into the Google search bar, hit Enter, and a definition will appear, along with results of other online dictionary pages that define the same word.

- Look away and get your mind off the target passage.

- Without looking back at the source text, repeat its main points as you understood them—not from memorizing the exact words, but as you would explain the same ideas in different words out loud to a friend.

- Still, without looking back at the source text, jot down that spoken wording and tailor the language so that it’s stylistically appropriate for your audience; edit and proofread your written version to make it grammatically correct in a way that perhaps your spoken-word version wasn’t.

- Now compare your written paraphrase version to the original to ensure that:

- You’ve accurately represented the meaning of the original without:

- Deleting any of the original points

- Adding any points of your own

- Distorting any of the ideas so they mean something substantially different from those in the original, or even take on a different character because you use words that, say, put a positive spin on something neutral or negative in the original

- You haven’t repeated any two identical words from the original in a row

- If any two words from the original remain, go further in changing those expressions by using a thesaurus in combination with a dictionary. When you enter a word into a thesaurus, it gives you a list of synonyms, which are different words that mean the same thing as the word you enter into it.

- Be careful, however; many of those words will mean the same thing as the word you enter into the thesaurus in certain contexts but not in others, especially if you enter a homonym, which is a word that has different meanings in different parts of speech.

- For instance, the noun party can mean a group that is involved in something serious (e.g., a third-party software company in a data-collection process), but the verb party means something you do on a wild Saturday night out with friends; it can also function as an adjective related to the verb (e.g., party trick, meaning a trick performed at a party).

- Whenever you see synonymous words listed in a thesaurus and they look like something you want to use but you don’t know what they mean exactly, always look them up to ensure that they mean what you hope they mean; if not, move on to the next synonym until you find one that captures the meaning you intend. Doing this can save your reader the confusion and you the embarrassment of obvious thesaurus-driven diction problems (poor word choices).

- Cite your source. Just because you didn’t put quotation marks around the words doesn’t mean that you don’t have to cite your source.

For more on paraphrasing, consult

- the Purdue OWL Paraphrasing learning module and Exercise

- NSCC Writing Centre

- NSCC Research Process Guide

- NSCC Academic Integrity Guide

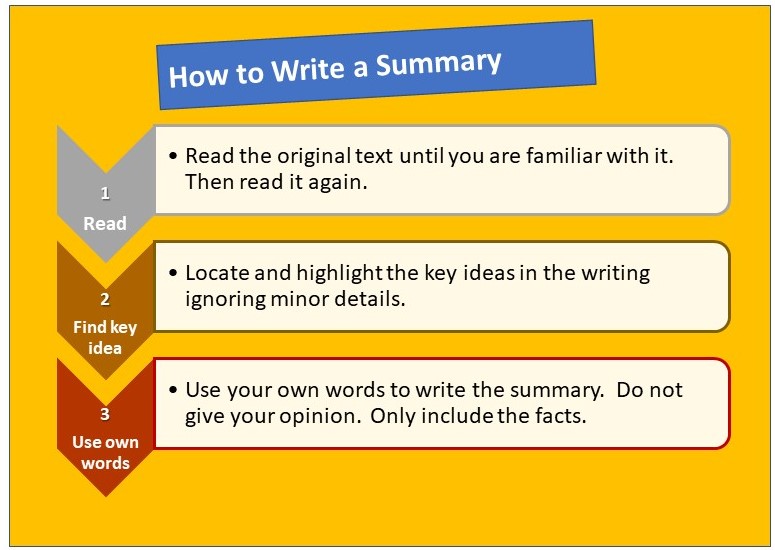

Summarizing Sources

Summarizing is one of the most important skills in communications because professionals of every kind must explain to non-expert customers, managers, and even co-workers complex concepts in a way non-experts can understand. Adapting the message to such audiences requires brevity and the ability to translate jargon-heavy technical details into plain, accessible language.

Summarizing is thus paraphrasing only the highlights of the original source. Like paraphrasing, a summary re-casts the original information in your own words and must be introduced; unlike a paraphrase, a summary is significantly shorter than the original text. A summary can reduce a whole novel, article, or film to a single-sentence.

The procedure for summarizing is much like that of paraphrasing except that it involves the extra step of pulling out highlights from the source. Altogether, this can be done in six steps, one of which includes the seven steps of paraphrasing, making this a twelve-step procedure:

- Determine how big your summary should be (according to your audience’s needs) so that you have a sense of how much material you should collect from the source.

- Read and re-read the source text so that you thoroughly understand it.

- Pull out the main points, which usually come first at any level of direct-approach organization (i.e., the prologue or introduction at the beginning of a book, the abstract at the beginning of an article, or the topic sentence at the beginning of a paragraph); review collecting sources above on reading for main points and below on organizational patterns.

- Disregard detail such as supporting evidence and examples.

- If you have an electronic copy of the source, copy and paste the main points into your notes; for a print source that you can mark up, use a highlighter then transcribe those main points into your electronic notes.

- How many points you collect depends on how big your summary should be (according to audience needs).

- Paraphrase those main points following the seven-step procedure for paraphrasing outlined in paraphrasing sources above.

- Edit your draft to make it coherent, clear, and especially concise.

- Ensure that your summary meets the needs of your audience and that your source is cited. Again, not having quotation marks around words doesn’t mean that you are off the hook for documenting your source(s).

Once you have a stable of summarized, paraphrased, and quoted passages from research sources, building your document around them requires good organizational skills. We’ll focus more on this next step of the drafting process in the following chapter, but basically, it involves arranging your integrated research material in a coherent fashion, with main points upfront and supporting points below proceeding in a logical sequence towards a convincing conclusion. Throughout this chapter, however, we’ve frequently encountered the requirement to document sources by citing and referencing, as in the last steps of both summarizing and paraphrasing indicated above. After reinforcing our quoting, paraphrasing, and summarizing skills, we can turn our focus on how to document sources.

Key Takeaway

Including research in your work typically involves properly quoting, paraphrasing, and/or summarizing source text, as well as citing it.

Including research in your work typically involves properly quoting, paraphrasing, and/or summarizing source text, as well as citing it.

Exercises

Find an example of professional writing in your field of study, perhaps from a textbook, trade journal, or industry website that you collected as part of the previous section’s informal annotated bibliography exercise.

Find an example of professional writing in your field of study, perhaps from a textbook, trade journal, or industry website that you collected as part of the previous section’s informal annotated bibliography exercise.

- If you’ve already pulled out the main points as part of the previous exercise, practice including them as properly punctuated quotations in your document with smooth signal phrases introducing them.

- Paraphrase those same main-point sentences following the seven-step procedure outlined in paraphrasing sources above. In other words, if Exercise 1 above was a direct quotation, now try indirect quotation for each passage.

- Following the six-step procedure outlined in summarizing sources above, summarize the entire source article, webpage, or whatever document you chose by reducing it to a single coherent paragraph of no more than 10 lines on your page.

References

Cimasko, T. (2013, March 22). Paraphrasing. Purdue OWL. Retrieved from https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/976/02/

Conrey, S. M., Pepper, M., & Brizee, A. (2013, April 3). Quotation mark exercise and answers. Purdue OWL. Retrieved from https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/577/05/

Conrey, S. M., Pepper, M., & Brizee, A. (2017, July 25). How to use quotation marks. Purdue OWL. Retrieved from https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/577/01/

Fairfieldulib. (2015). How to paraphrase [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iJ9DOE91oiw.

Hacker, Diana. (2006). The Bedford handbook (7th ed.). New York: St. Martin’s. Retrieved from https://department.monm.edu/english/mew/signal_phrases.htm

Lester, J. D. (1976). Writing research papers: A complete guide (2nd ed.). Glenview, Illinois: Scott, Foresman.

PPCC Writing Center elearning Series. (2016). Part 2 Quoting [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=do921cAEL6o&t=51s