Unit 24: Information Shares, Action Requests, and Replies

Learning Objectives

After reading this unit, you will be able to

After reading this unit, you will be able to

-

-

- understand the difference between different types of routine messages

- understand how to components of different types of routine message messages

-

Introduction

Ask any professional what kinds of messages they spend the majority of their time at a computer writing and responding to. They will likely tell you that they’re writing an email, memo or letter requesting information or action and replying to those with answers or acknowledgments. To write these types of documents you may need to polish your style, grammar and organization to meet a professional standard. After all, the quality of the responses you get or can give crucially depends on the quality of the questions you ask or are asked. Before looking specifically at each document type, let’s take a minute to watch a video introduction to routine business correspondence.

Information Shares

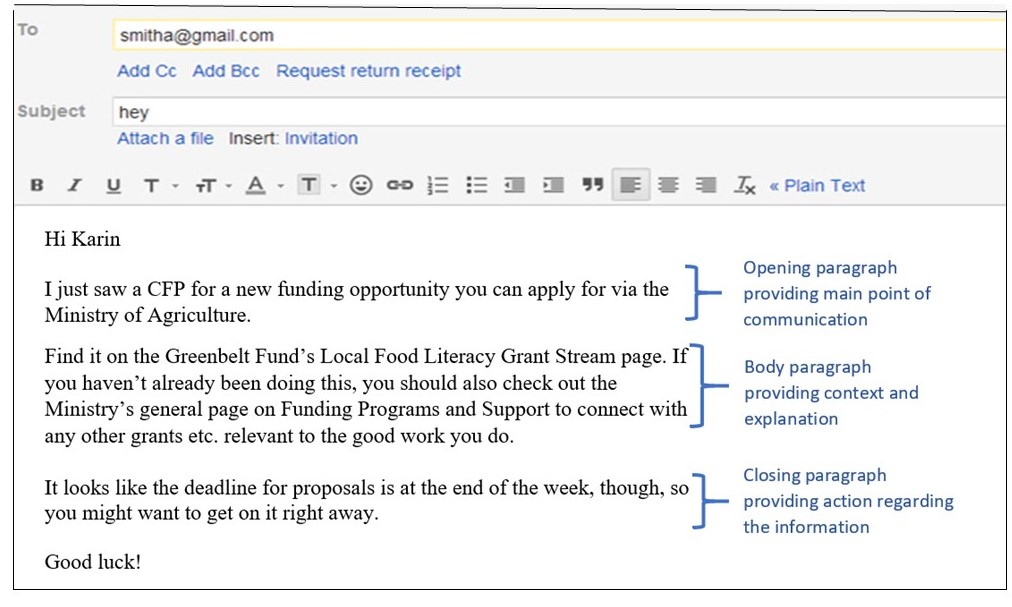

Perhaps the simplest and most common routine message type is where the sender offers up information that helps the receiver. These may not be official memos, but they follow the same structure, as shown in Figure 24.1 below.

Notice here how the writer made the reader’s job especially easy by providing links to the recommended webpages using the hyperlinking feature (Ctrl. + K) in their email.

Replies to such information shares involve either a quick and concise thank-you message (see unit 28) or carry the conversation on if it’s part of an ongoing project, initiative, or conversation. Recall that you should change the email subject line as the topic evolves (see unit 17). Information shares to a large group, such as a departmental memo to 60 employees, don’t usually require acknowledgment and would be slightly more formal in tone. If everyone wrote the sender just to say thanks, the barrage of reply notifications would frustrate them as they try to carry on their work while sorting out replies with valuable information from mere acknowledgments. Only respond if you have valuable information to share with all the recipients or just the sender.

Information or Action Requests

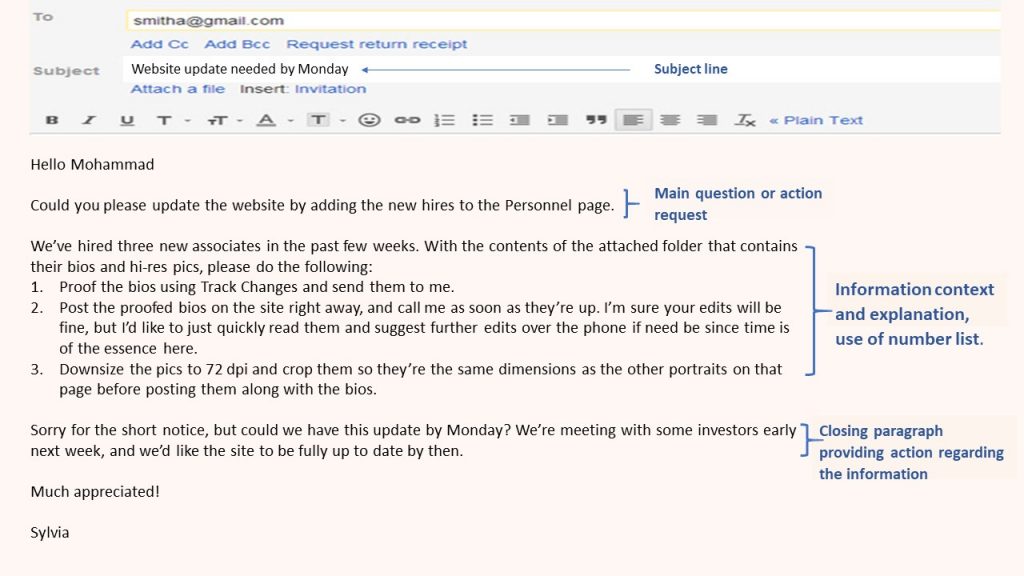

Managers, clients, and coworkers alike send and receive requests for information and action all day. Because these provide the recipient with direction on what to do, the information that comes back or action that results from such requests can only be as good as the instructions given. Such messages must therefore be well organized and clear about expectations, opening directly with a clearly stated general request (see unit 11 on direct-approach messages)—unless you anticipate resistance to the request (see unit 11 on indirect-approach messages)—and proceeding with background and more detailed instruction if necessary as we see in Figure 24.2 below.

Note that, because you’re expecting action to come of the request rather than a yes or no answer, the opening question doesn’t require a question mark. Never forget, however, the importance of saying “please” when asking someone to do something (see unit 13 for more on courteous language). Notice also that lists in the message body help break up dense detail so that request messages are more reader-friendly (see unit 14). All of the efforts that the writer of the above message made to deliver a reader-friendly message will pay off when the recipient performs the requested procedure exactly according to these clearly worded expectations.

Instructional Messages

Effective organization and style are critical in requests for action that contain detailed instructions. Whether you’re explaining how to operate equipment, apply for funding, renew a membership, or submit a payment, the recipient’s success depends on the quality of the instruction. Vagueness and a lack of detail can result in confusion, mistakes, and requests for clarification. Too much detail can result in frustration, skimming, and possibly missing key information. Profiling the audience and gauging their level of knowledge is key (see unit 5 on analyzing your audience) to providing the appropriate level of detail for the desired results.

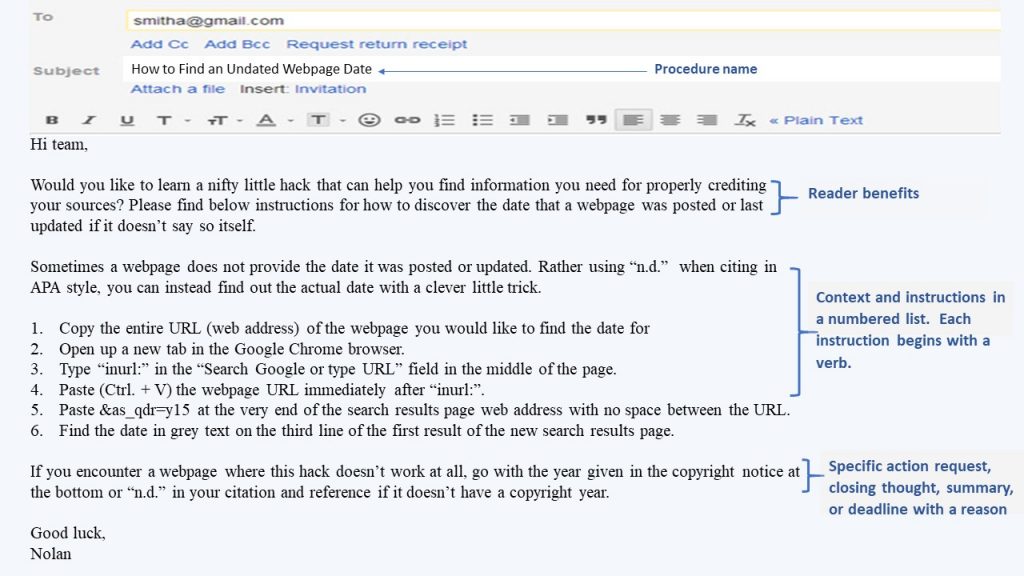

Look at any procedures document and you’ll see that the quality of its readability depends on the instructions being organized in a numbered list of parallel imperative sentences. As opposed to the indicative sentences that have a grammatical subject and predicate (like most sentences you see here), imperative sentences drop the subject (the doer of the action, which is assumed to be the reader in the case of instructions). This omission leaves just the predicate, which means that the sentence starts with a verb. In Table 24.3 below, for instance, the reader can easily follow the directions by seeing each of the six main steps open with a simple verb describing a common computer operation: Copy, Open, Type, Paste (twice), and Find.

If you begin any imperative sentence with a prepositional (or other) phrase to establish some context for the action first (such as this imperative sentence does), move the adverb after the verb and the phrase to the end of the sentence. (If the previous sentence followed its own advice, it would look like this: Move the adverb after the verb and the phrase to the end of the imperative sentence if you begin it with a prepositional (or other) phrase to establish some context for the action first.) Finally, surround the list with a proper introduction and closing as shown in Figure 24.4 below.

Though helpful on its own, the above message would be much improved if it included illustrative screenshots at each step. Making a short video of the procedure, posting it to YouTube, and adding the link to the message would be even more effective.

Combining DOs and DON’Ts is an effective way to help your audience complete the instructed task without making common rookie mistakes. Always begin with the DOs after explaining the benefits or rewards of following a procedure, not with threats and heavy-handed ‘Thou shalt nots”. You can certainly follow up with helpful DON’Ts and consequences if necessary, but phrased in courteous language, such as “please remember to exercise caution in construction areas.”

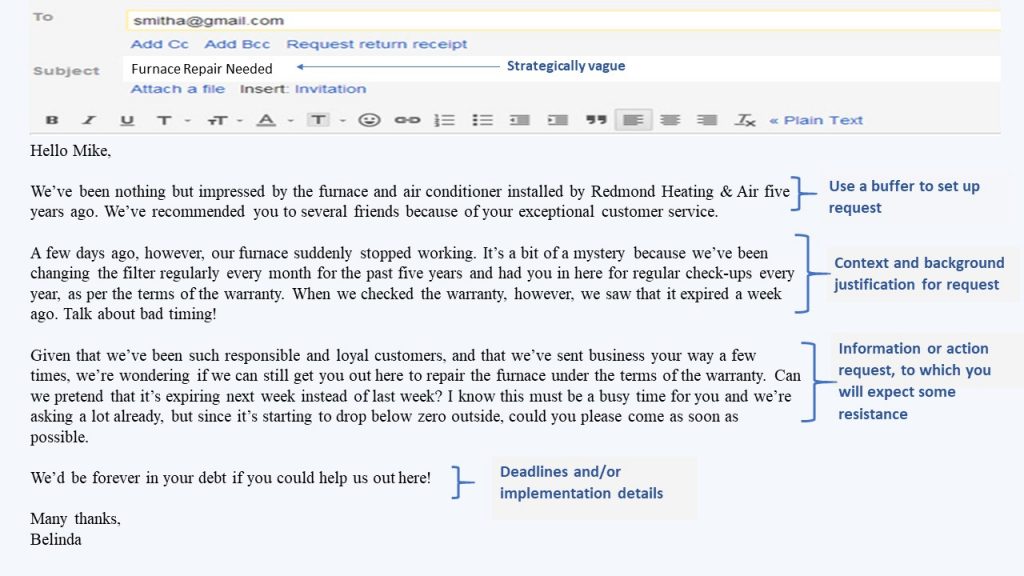

Indirect Information or Action Requests

If you expect resistance to your request, an indirect approach is more effective (see unit 11 on indirect message organization). Ideally, you’ll make such persuasive pitches in person or on the phone so that you can use a full range of verbal and non-verbal cues (see unit 27 on persuasive messages). When it’s important to have present your argument in writing, however, such requests should be clear and easy to spot, but buffered by goodwill statements and reasonable justifications, as shown in Figure 24.5 below.

Replies to Information or Action Requests

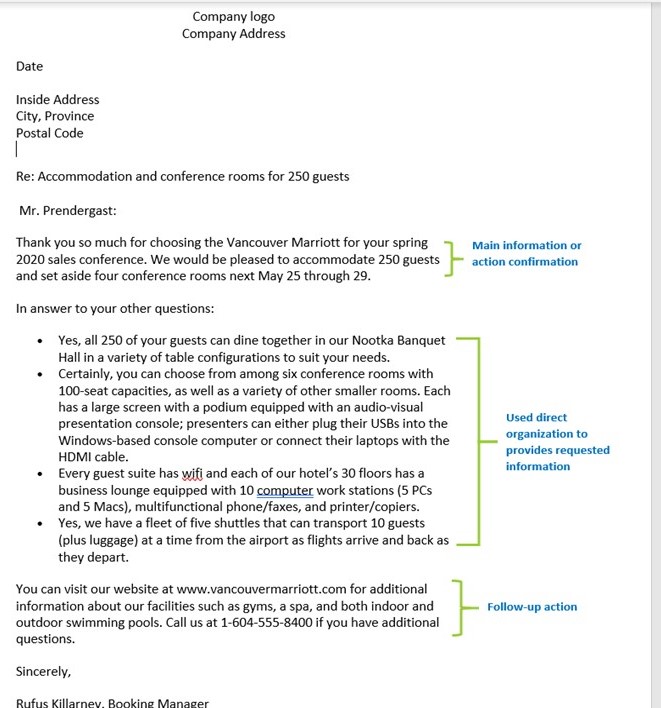

When responding to information or action requests, simply deliver the needed information or confirm that the action has been or will be completed unless you have good reasons for refusing (see unit 26 on negative messages). Stylistically, such responses should follow the 6 Cs of effective business style (see unit 13 ), especially courtesies such as prioritizing the “you” view (unit 13), audience benefits (unit 13), and saying “please” for follow-up action requests (unit 13). Such messages are opportunities to promote your company’s products and services. Ensure the accuracy of all details, however, because courts will consider them legally binding, even in an email, if disputes arise—as the Vancouver Canucks organization discovered in a battle with Canon (Smith, 2015). Manager approval may be necessary before sending. Organizationally, a positive response to an information request delivers the main answer in the opening, proceeds to give more detail in the body if necessary, and ends politely with appreciation and goodwill statements, as shown in Figure 24.6 below.

Key Takeaway

Follow best practices when sharing information, requesting information or action, and replying to such messages.

Follow best practices when sharing information, requesting information or action, and replying to such messages.

Exercises

Pick a partner and email them a set of instructions following the message outline template and example given in Table 24.3. It must be a procedure with at least five steps and is familiar to you but unfamiliar to them. Can they follow your procedure and get the results you desire?

Pick a partner and email them a set of instructions following the message outline template and example given in Table 24.3. It must be a procedure with at least five steps and is familiar to you but unfamiliar to them. Can they follow your procedure and get the results you desire?

References

Gatbondon, G. (2019). Chapter 8: Writing routine and positive messages (MG206) [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uFUsqgqIMXY

Gregg Learning. (2019). How to write instructions for business [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kIiQcQVr9H0

Smith, C. L. (2015, May 8). Canada: When does an email form a legally binding agreement? Ask the Canucks. Retrieved from http://www.mondaq.com/canada/x/395584/Contract+Law/When+Does+An+Email+Form+A+LegallyBinding+Agreement+Ask+The+Canucks

A meaningful but neutral statement that cushions the impact of bad news.