6. Ethics and Social Responsibility

Learning Objectives

By the end of the chapter, you should be able to:

- Define business ethics and explain what it means to act ethically in business.

- Explain why we study business ethics.

- Identify ethical issues that you might face in business, such as insider trading, conflicts of interest, and bribery, and explain rationalizations for unethical behaviour.

- Identify steps you can take to maintain your honesty and integrity in a business environment.

- Define corporate social responsibility and explain how organizations are responsible to their stakeholders, including owners, employees, customers, and the community.

- Discuss how you can identify an ethical organization, and how organizations can prevent behaviour like sexual harassment.

- Recognize how to avoid an ethical lapse, and why you should not rationalize when making decisions.

Show What You Know

Canada’s Leader: Passing or Failing the “Smell Test”?

Ethics is not always black and white; the ethical decision is not always obvious to all. Even leaders can fail to act ethically all the time. Recent decisions impacted two leaders.

CBC News’s reporter, E. Thompson, filed the following story on December 21, 2017. It provides a detailed account of the ethical issues surrounding Prime Minister Trudeau’s trip to Aga Khan’s private island.

CBC NEWS – Aga Khan could face lobbying probe for Trudeau trip[1]

CBC NEWS – Aga Khan could face lobbying probe for Trudeau trip[1]Democracy Watch (http://democracywatch.ca/) files complaint, saying Bahamas vacation violated lobbying law.

The Aga Khan could face an investigation into allegations he violated Canada’s Lobbying Act by giving Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and his family free vacations on his private island in the Bahamas at the same time as he was discussing funding for projects.

Democracy Watch sent a letter to the Commissioner of Lobbying late Wednesday, urging her to investigate whether Prince Shah Karim Al Hussaini Aga Khan IV “violated the Lobbyists Code by giving Prime Minister Trudeau and Liberal MP Seamus O’Regan the gifts of trips to his island home”.

In the letter, Democracy Watch co-founder Duff Conacher says the Aga Khan’s actions have put Trudeau and O’Regan in a conflict of interest. It is also against the law to give a public office holder a gift that could create a sense of obligation.

“Your position must be that anyone working for or associated with a company that is registered to lobby a public office holder who gives to or does anything for that office holder… that is more than an average voter does… puts that office holder in an apparent conflict of interest,” he wrote.

The Aga Khan is the spiritual leader of millions of Ismaili Muslims and is listed as a member of the board of directors of the Aga Khan Foundation Canada. The foundation, which has received millions of dollars in federal government development aid over the years, is registered to lobby several federal government departments including the Prime Minister’s Office, although the Aga Khan is not listed among those registered to lobby on its behalf.

A search of the lobbyist registry shows the foundation has filed 132 reports since 2011 outlining its meetings with government decision makers. However, none of those reports list any meetings with Trudeau.

Representatives of the Aga Khan Foundation of Canada contacted by CBC News have yet to comment.

The call for a lobbying investigation comes in the wake of a scathing report by Ethics Commissioner Mary Dawson on Wednesday.

Dawson found that Trudeau violated four sections of the Conflict of Interest Act when he accepted a vacation on the island in the Bahamas and a ride in the Aga Khan’s personal helicopter.

While Trudeau and his family got a tropical vacation, Canadian taxpayers got a bill for more than $215,000 in transportation and staffing costs — far more than the government initially disclosed to Parliament.

Dawson also revealed that Trudeau’s trip during last year’s Christmas holidays was one of three that Trudeau or members of his family had made to the island. Dawson disclosed that Sophie Grégoire-Trudeau stayed on the island in March 2016 with a friend and their children.

Neither the Aga Khan, nor any member of his family, was on the island during their stay.

Dawson said the Aga Khan was on the island during the Trudeaus’ Christmas-time visit last year as was a “senior American official of a previous administration,” who she did not name.

In her report, Dawson describes the relationship between Trudeau and the Aga Khan, the times they met and the questions they discussed.

Among them was a bilateral meeting on May 17, 2016 that was arranged by “representatives” of the Aga Khan. After a 15-minute chat between the two men about “personal matters, the Ismaili community in general and geopolitics,” they were joined by three of the Aga Khan’s representatives, Heritage Minister Mélanie Joly, staff members from the Prime Minister’s Office and senior officials of the Privy Council Office.

Dawson’s report says the government had found a funding mechanism to allow it to contribute to the Global Centre for Pluralism’s endowment fund and Trudeau reaffirmed the government’s $15 million commitment during the meeting.

The Aga Khan’s pitch for government funding for a $200 million riverfront renewal plan in Ottawa was also discussed.

Dawson ruled that Trudeau should have recused himself from two discussions in May 2016 involving the $15 million grant.

“Two months prior to the May 2016 occasions, Mr. Trudeau’s family accepted a gift from the Aga Khan that might reasonably be seen to have been given to influence Mr. Trudeau in the exercise of an official power, duty or function as Prime Minister,” she wrote.

“For this reason, the discussions with the Privy Council Office and later with the Aga Khan about the outstanding $15 million grant to the endowment fund provided an opportunity to improperly further the private interests of the Global Centre for Pluralism.”

While the Aga Khan is not paid to lobby government (one of the criteria under the law) Conacher said he believes the Aga Khan violated the lobbying rules. Otherwise, it would create a giant loophole, he said.

“Every single corporation, business, union, non-profit organization would start using board members to give gifts to politicians if this loophole were opened up by the lobbying commissioner.”

Conacher is also calling for outgoing lobbying commissioner Karen Shepherd and incoming lobbying commissioner Nancy Bélanger to recuse themselves from ruling on the investigation because of the way Shepherd’s contract was renewed and the way Bélanger was chosen in “a secretive, PMO-controlled process.”

Manon Dion, spokeswoman for the lobbying commissioner’s office, said she cannot reveal whether they are already looking into the issue.

Point to Ponder

Could the Prime Minister and family have taken an ethical version of this vacation? If yes, how? If not, why not?

The Prime Minister’s Response: http://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/trudeau-ethics-aga-khan-1.4458220

The Ethics Commissioner’s Report: https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/4334047-The-Trudeau-Report.html

Moving Ethics To the Business World

Perhaps you have heard of Bernie Madoff, founder of Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities and former chairman of the NASDAQ stock exchange.[2] Madoff is alleged to have run a giant Ponzi scheme[3] that cheated investors of up to $65 billion. His wrongdoings won him a spot at the top of Time Magazine’s Top 10 Crooked CEOs. According to the SEC charges, Madoff convinced investors to give him large sums of money. In return, he gave them an impressive 8 percent to 12 percent return a year. But Madoff never really invested their money. Instead, he kept it for himself. He got funds to pay the first investors their return (or their money back if they asked for it) by bringing in new investors. Everything was going smoothly until the fall of 2008, when the stock market plummeted and many of his investors asked for their money. As he no longer had it, the game was over and he had to admit that the whole thing was just one big lie. Thousands of investors, including many of his wealthy friends, not-so-rich retirees who trusted him with their life savings, and charitable foundations, were financially ruined. Those harmed by Madoff either directly or indirectly were likely pleased when he was sentenced to jail for one-hundred and fifty years.

What is Business Ethics?

The Idea of Business Ethics

It’s in the best interest of a company to operate ethically. Trustworthy companies are better at attracting and keeping customers, talented employees, and capital. Those tainted by questionable ethics suffer from dwindling customer bases, employee turnover, and investor mistrust.

Let’s begin this section by addressing this question: What can individuals, organizations, and government agencies do to foster an environment of ethical behaviour in business? First, of course, we need to define the term.

What Is Ethics?

You probably already know what it means to be ethical: to know right from wrong and to know when you’re practising one instead of the other. Business ethics is the application of ethical behaviour in a business context. Acting ethically in business means more than simply obeying applicable laws and regulations. It also means being honest, doing no harm to others, competing fairly, and declining to put your own interests above those of your company, its owners, and its workers. If you’re in business you obviously need a strong sense of what’s right and wrong. You need the personal conviction to do what’s right, even if it means doing something that’s difficult or personally disadvantageous.

Why Study Ethics?

Ideally, prison terms, heavy fines, and civil suits would discourage corporate misconduct, but, unfortunately, many experts suspect that this assumption is a bit optimistic. Whatever the condition of the ethical environment in the near future, one thing seems clear: the next generation entering business—which includes most of you—will find a world much different than the one that waited for the previous generation. Recent history tells us in no uncertain terms that today’s business students, many of whom are tomorrow’s business leaders, need a much sharper understanding of the difference between what is and isn’t ethically acceptable. As a business student, one of your key tasks is learning how to recognize and deal with the ethical challenges that will confront you. Asked what he looked for in a new hire, Warren Buffet, the world’s most successful investor, replied: “I look for three things. The first is personal integrity, the second is intelligence, and the third is a high energy level.” He paused and then added: “But if you don’t have the first, the second two don’t matter”.[4]

Identifying Ethical Issues and Dilemmas

Ethical issues are the difficult social questions that involve some level of controversy over what is the right thing to do. Environmental protection is an example of a commonly discussed ethical issue, because there can be trade-offs between environmental and economic factors.

Tips to maintain honesty and integrity

- Follow your own code of personal conduct; act according to your own convictions rather than doing what’s convenient (or profitable) at the time.

- While at work, focus on your job, not on non-work related activities, such as emails and personal phone calls.

- Don’t appropriate office supplies or products or other company resources for your own use.

- Be honest with customer, management, coworkers, competitors, and the public.

- Remember that it’s the small seemingly trivial, day-to-day activities and gestures that build your character.

Make no mistake about it: when you enter the business world, you’ll find yourself in situations in which you’ll have to choose the appropriate behaviour. How, for example, would you answer questions like the following?

- Is it OK to accept a pair of sports tickets from a supplier?

- Can I buy office supplies from my brother-in-law?

- Is it appropriate to donate company funds to a local charity?

- If I find out that a friend is about to be fired, can I warn her?

Obviously, the types of situations are numerous and varied. Fortunately, we can break them down into a few basic categories: issues of honesty and integrity, conflicts of interest and loyalty, bribes versus gifts, and whistle-blowing. Let’s look a little more closely at each of these categories.

Issues of Honesty and Integrity

Master investor Warren Buffet once told a group of business students the following: “I cannot tell you that honesty is the best policy. I can’t tell you that if you behave with perfect honesty and integrity somebody somewhere won’t behave the other way and make more money. But honesty is a good policy. You’ll do fine, you’ll sleep well at night and you’ll feel good about the example you are setting for your coworkers and the other people who care about you”.[5]

If you work for a company that settles for its employees’ merely obeying the law and following a few internal regulations, you might think about moving on. If you’re being asked to deceive customers about the quality or value of your product, you’re in an ethically unhealthy environment.

Think about this story:

“A chef put two frogs in a pot of warm soup water. The first frog smelled the onions, recognized the danger, and immediately jumped out. The second frog hesitated: The water felt good, and he decided to stay and relax for a minute. After all, he could always jump out when things got too hot (so to speak). As the water got hotter, however, the frog adapted to it, hardly noticing the change. Before long, of course, he was the main ingredient in frog-leg soup.”[6]

So, what’s the moral of the story? Don’t sit around in an ethically toxic environment and lose your integrity a little at a time; get out before the water gets too hot and your options have evaporated.

Conflicts of Interest

Conflicts of interest occur when individuals must choose between taking actions that promote their personal interests over the interests of others or taking actions that don’t. A conflict can exist, for example, when an employee’s own interests interfere with, or have the potential to interfere with, the best interests of the company’s stakeholders (management, customers, and owners). Let’s say that you work for a company with a contract to cater events at your college and that your uncle owns a local bakery. Obviously, this situation could create a conflict of interest (or at least give the appearance of one—which is a problem in itself). When you’re called on to furnish desserts for a luncheon, you might be tempted to send some business your uncle’s way even if it’s not in the best interest of your employer. What should you do? You should disclose the connection to your boss, who can then arrange things so that your personal interests don’t conflict with the company’s.

The same principle holds that an employee shouldn’t use private information about an employer for personal financial benefit. Say that you learn from a coworker at your pharmaceutical company that one of its most profitable drugs will be pulled off the market because of dangerous side effects. The recall will severely hurt the company’s financial performance and cause its stock price to plummet. Before the news becomes public, you sell all the stock you own in the company. What you’ve done is called insider trading – acting on information that is not available to the general public, either by trading on it or providing it to others who trade on it. Insider trading is illegal, and you could go to jail for it.

Conflicts of Loyalty

You may one day find yourself in a bind between being loyal either to your employer or to a friend or family member. Perhaps you just learned that a coworker, a friend of yours, is about to be downsized out of his job. You also happen to know that he and his wife are getting ready to make a deposit on a house near the company headquarters. From a work standpoint, you know that you shouldn’t divulge the information. From a friendship standpoint, though, you feel it’s your duty to tell your friend. Wouldn’t he tell you if the situation were reversed? So what do you do? As tempting as it is to be loyal to your friend, you shouldn’t tell. As an employee, your primary responsibility is to your employer. You might be able to soften your dilemma by convincing a manager with the appropriate authority to tell your friend the bad news before he puts down his deposit.

Bribes Versus Gifts

It’s not uncommon in business to give and receive small gifts of appreciation, but when is a gift unacceptable? When is it really a bribe?

There’s often a fine line between a gift and a bribe. The following information may help in drawing it, because it raises key issues in determining how a gesture should be interpreted: the cost of the item, the timing of the gift, the type of gift, and the connection between the giver and the receiver. If you’re on the receiving end, it’s a good idea to refuse any item that’s overly generous or given for the purpose of influencing a decision. Because accepting even small gifts may violate company rules, always check on company policy.

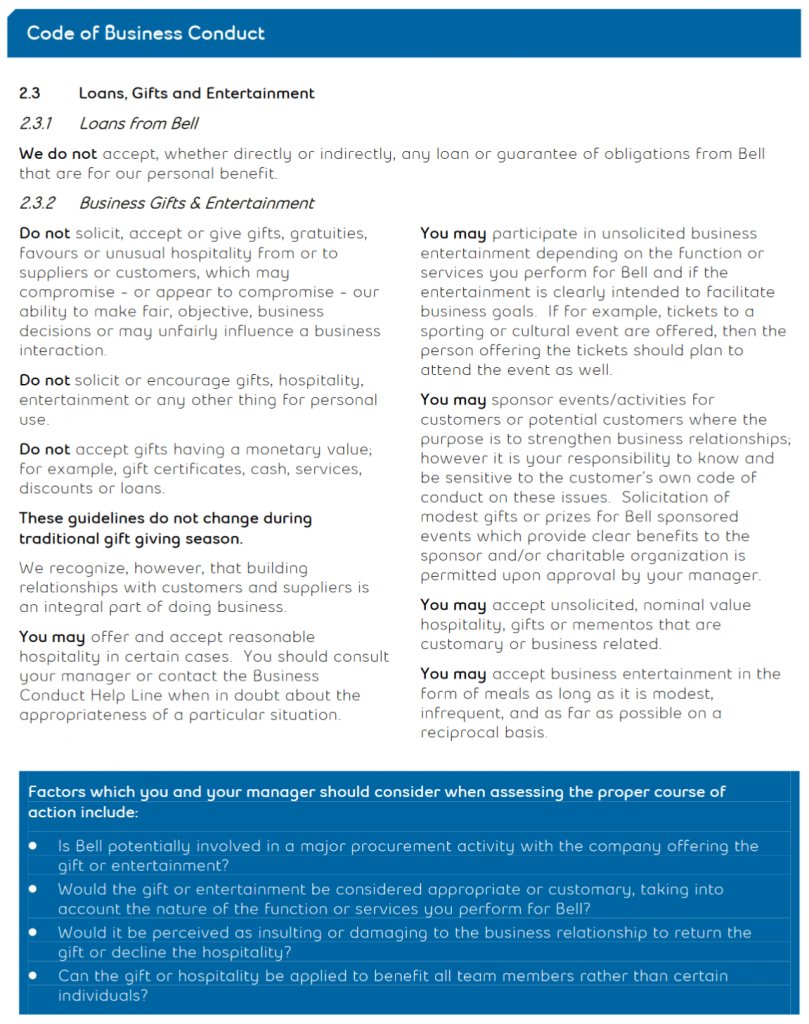

Read through Figure 6.2, Bell Canada’s Code of Business Conduct detailing its recommendations for gifts. If you cannot access Figure 6.2, find it on page 10 of the document (http://www.bce.ca/governance/code-of-business-conduct/2017-august-code-of-business-conduct.pdf).

Whistleblowing

Whistleblowing was defined in 1972 by Ralph Nader as “an act of a man or a woman who, believing in the public interest overrides the interest of the organization he serves, publicly blows the whistle if the organization is involved in corrupt, illegal, fraudulent or harmful activity”.

While there are increasing incentives from governments and regulators for whistleblowers to go public about corporate misconduct, protections for whistleblowers are still very limited. Few Canadian laws pertain directly to whistleblowing and therefore whistleblowers are mostly unprotected by statute.

There is, however, a patchwork of protection provisions for whistleblowers under the Canadian Criminal Code, Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act (PSDPA), the Public Service of Ontario Act, 2006 as well as the Securities Act.

Section 425.1 (http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/C-46/page-90.html#h-113) of the Criminal Code, for example, states that employers may not threaten or take disciplinary action against, demote or terminate an employee in order to deter her/him from reporting information regarding an offence s/he believes has or is being committed by her/his employer to the relevant law enforcement authorities.

An employer cannot threaten an employee with negative repercussions to deter them from contacting law enforcement with information about the employer’s offence. Punishment for employers who make such threats or reprisals can include up to five years imprisonment and/or fines.

In early 2018, a Canadian whistleblower received worldwide recognition for disclosing the amount and kinds of data harvested by Cambridge Analytica through personal Facebook accounts. However, there are other, prominent Canadian whistleblowers (https://www.cfe.ryerson.ca/key-resources/lists/prominent-canadian-whistleblowers).

Corporate Social Responsibility

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) refers to the approach that an organization takes in balancing its responsibilities toward different stakeholders when making legal, economical, ethical, and social decisions. Remember that we previously define stakeholders as those with a legitimate interest in the success or failure of the business and the policies it adopts. The term social responsibility refers to the approach that an organization takes in balancing its responsibilities toward their various stakeholders.

What motivates companies to be “socially responsible”? We hope it’s because they want to do the right thing, and for many companies , “doing the right thing” is a key motivator. The fact is, it’s often hard to figure out what the “right thing” is: what’s “right” for one group of stakeholders isn’t necessarily “right” for another. One thing, however, is certain: companies today are held to higher standards than ever before. Consumers and other groups consider not only the quality and price of a company’s products but also its character. If too many groups see a company as a poor corporate citizen, it will have a harder time attracting qualified employees, finding investors, and selling its products. Good corporate citizens, by contrast, are more successful in all these areas.

Another Lens[8]

Carroll’s Pyramid is a well-respected resource for situating corporate social responsibility. Another view of corporate social responsibility is from the perspective of a company’s relationships with its stakeholders. In this model, the focus is on managers—not owners—as the principals involved in these relationships. Owners are the stakeholders who invest risk capital in the firm in expectation of a financial return. Other stakeholders include employees, suppliers, and the communities in which the firm does business. Proponents of this model hold that customers, who provide the firm with revenue, have a special claim on managers’ attention. The arrows in Figure 6.3 indicate the two-way nature of corporation-stakeholder relationships. All stakeholders have some claim on the firm’s resources and returns, and management’s job is to make decisions that balance these claims.[9]

Let’s look at some of the ways in which companies can be “socially responsible” in considering the claims of various stakeholders.

Owners

Owners invest money in companies. In return, the people who run a company have a responsibility to increase the value of owners’ investments through profitable operations. Managers also have a responsibility to provide owners (as well as other stakeholders having financial interests, such as creditors and suppliers) with accurate, reliable information about the performance of the business. Clearly, this is one of the areas in which WorldCom managers fell down on the job. Upper-level management purposely deceived shareholders by presenting them with fraudulent financial statements

Managers

Managers have what is known as a fiduciary responsibility to owners: they’re responsible for safeguarding the company’s assets and handling its funds in a trustworthy manner. Yet managers experience what is called the agency problem; a situation in which their best interests do not align with those of the owners who employ them. To enforce managers’ fiduciary responsibilities for a firm’s financial statements and accounting records, Ontario’s Keeping the Promise for a Strong Economy Act (Budget Measures) 2002, also known as Bill 198, (Canadian equivalent to Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 in the United States) requires CEOs and CFOs to attest to their accuracy. The law also imposes penalties on corporate officers, auditors, board members, and any others who commit fraud. You’ll learn more about this law in your accounting and business law courses.

Employees

Companies are responsible for providing employees with safe, healthy places to work—as well as environments that are free from sexual harassment and all types of discrimination. They should also offer appropriate wages and benefits. In the following sections, we’ll take a closer look at these areas of corporate responsibility.

Wages and Benefits

At the very least, employers must obey laws governing minimum wage and overtime pay. A minimum wage is set by the provincial government. As of January 1, 2018, the Ontario rate is $14.00 with another increase to $15.00 set for January 1, 2019. By law, employers must also provide certain benefits—Canadian Pension Plan (CPP -retirement funds), unemployment insurance (protects against loss of income in case of job loss), and depending on the industry, workers’ compensation (covers lost wages and medical costs in case of on-the-job injury). Most large companies pay most of their workers more than minimum wage and offer broader benefits, including medical, dental, and vision care, as well as savings programs, in order to compete for talent.

Safety and Health

Though it seems obvious that companies should guard workers’ safety and health, some simply don’t. For over four decades, for example, executives at Johns Manville suppressed evidence that one of its products, asbestos, was responsible for the deadly lung disease developed by many of its workers.[10] The company concealed chest X- rays from stricken workers, and executives decided that it was simply cheaper to pay workers’ compensation claims than to create a safer work environment. A New Jersey court was quite blunt in its judgment: Johns Manville, it held, had made a deliberate, cold-blooded decision to do nothing to protect at-risk workers, in blatant disregard of their rights.[11]

In The Globe and Mail’s 2017 article, “Statistics Canada looks to close data gap on workplace death, injuries” examines the different, Canadian landscape on safety and health.

Currently, responsibility for workers’ compensation and occupational health and safety issues falls largely to provinces or territories – and each jurisdiction has different approaches in capturing data. As a result, there’s an “uneven landscape” of health and safety research capacity, said Barbara Neis, co-founder and senior research associate at the SafetyNet Centre for Occupational Health and Safety Research at Memorial University.

The last time Statistics Canada produced a national analysis was in 1996.

Responsibility for fatality and injury counts, which are based on accepted workers’ compensation claims, shifted over to the Association of Workers’ Compensation Boards at that time. Detailed data must be purchased, and researchers say these counts don’t represent the whole workforce, partly because not all sectors or types of workers are included in the workers’ compensation system.

Available workers’ compensation numbers show about 350 Canadians die each year from an on-the-job injury at work. If longer-term work-related illnesses (such as mesothelioma from asbestos exposures, or lung cancers from silica dust) are factored in, this number climbs to about 1,000 deaths a year.

Customers

The purpose of any business is to satisfy customers, who reward businesses by buying their products. Sellers are also responsible—both ethically and legally—for treating customers fairly. This means customers have:

- The right to safe products. A company should sell no product that it suspects of being unsafe for buyers. Thus, producers have an obligation to safety-test products before releasing them for public consumption. The automobile industry, for example, conducts extensive safety testing before introducing new models (though recalls remain common).

- The right to be informed about a product. Sellers should furnish consumers with the product information that they need to make an informed purchase decision. That’s why pillows have labels identifying the materials used to make them, for instance.

- The right to choose what to buy. Consumers have a right to decide which products to purchase, and sellers should let them know what their options are. Pharmacists, for example, should tell patients when a prescription can be filled with a cheaper brand-name or generic drug. Telephone companies should explain alternative calling plans.

- The right to be heard. Companies must tell customers how to contact them with complaints or concerns. They should also listen and respond.

Companies share the responsibility for the legal and ethical treatment of consumers with several government agencies.

In Canada, consumer complaints are regulated by different levels of government, as well as non-government organizations. Finding the right place to direct your complaint is not always easy, but understanding your rights as a consumer is an important part of the complaint filing process.

Provincial and territorial consumer protection legislation

Many consumer complaints fall under provincial and territorial jurisdiction, including issues related to:

- buying goods and services;

- contracts;

- the purchase, maintenance or repair of motor vehicles;

- credit reporting agencies and the practices of collection agencies.

Federal consumer protection legislation

The Government of Canada has an important role in consumer awareness and protection.

Federal agencies and departments are responsible for enforcing legislation related to various issues, including:

- consumer product safety;

- food safety;

- consumer product packaging and labelling;

- anti-competitive practices, such as price fixing and misleading advertising;

- privacy complaints.

Reproduced from the Federal Office of Consumer Affairs

Government of Canada. (2018). Consumer protection legislation in Canada. Office of Consumer Affairs. https://www.ic.gc.ca/eic/site/Oca-bc.nsf/eng/ca02965.html?Open=1&

Communities

For obvious reasons, most communities see getting a new business as an asset and view losing one—especially a large employer—as a detriment. After all, the economic impact of business activities on local communities is substantial: they provide jobs, pay taxes, and support local education, health, and recreation programs. Both big and small businesses donate funds to community projects, encourage employees to volunteer their time, and donate equipment and products for a variety of activities. Larger companies can make greater financial contributions. Let’s start by taking a quick look at the philanthropic activities of a few U.S. corporations.

Philanthropy

Many large corporations support various charities, an activity called philanthropy. Some donate a percentage of sales or profits to worthwhile causes. Retailer Target, for example, donates 5 percent of its profits—about $2 million per week—to schools, neighborhoods, and local projects across the country; its store-based grants underwrite programs in early childhood education, the arts, and family-violence prevention.[12] The late actor Paul Newman donated 100 percent of the profits from “Newman’s Own” foods (salad dressing, pasta sauce, popcorn, and other products sold in eight countries). His company continues his legacy of donating all profits and distributing them to thousands of organizations, including the Hole in the Wall Gang camps for seriously ill children.[13]

Across the border, Canadian companies also show their philanthropic side. Tim Horton’s Children’s Foundation sends 19,000 kids to camp each summer, who would otherwise not have the resources to attend.[14] Its Timbits Minor Sports Program supports the participation of 300 000 kids in their pursuit of hockey, soccer, lacrosse, softball, baseball, and ringette[15]. In 2017, Loblaw Companies and its President’s Choice Children’s Charity pledged $150 million over the next decade to address childhood hunger in Canada.[16] These are just two examples of Canadian companies giving back at the local and national levels.

Ethical Organizations

How Can You Recognize an Ethical Organization?

One goal of anyone engaged in business should be to foster ethical behaviour in the organizational environment. How do we know when an organization is behaving ethically? Most lists of ethical organizational activities include the following criteria:

- Treating employees, customers, investors, and the public fairly

- Holding every member personally accountable for his or her action

- Communicating core values and principles to all members

- Demanding and rewarding integrity from all members in all situations[17]

Employees at companies that consistently make Business Ethics magazine’s list of the “100 Best Corporate Citizens” regard the items on the previous list as business as usual in the workplace. Companies at the top of the 2016 list include Microsoft, Hasbro, Ecolab, Bristol-Myers-Squibb, and Lockheed Martin.[18]

By contrast, employees with the following attitudes tend to suspect that their employers aren’t as ethical as they should be:

- They consistently feel uneasy about the work they do.

- They object to the way they’re treated.

- They’re uncomfortable about the way coworkers are treated.

- They question the appropriateness of management directives and policies.[19]

Sexual Harassment

Sexual harassment occurs when an employee makes “unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favours, and other verbal or physical conduct of a sexual nature” to another employee. It’s also considered sexual harassment when “submission to or rejection of this conduct explicitly or implicitly affects an individual’s employment, unreasonably interferes with an individual’s work performance or creates an intimidating, hostile or offensive work environment.”[20]

Sexual harassment rocketed to the top of news reports and social media when on October 5, 2017, The New York Times broke the story of Harvey Weinstein’s decades of harassment in Hollywood. In March of 2018, CBC News collated the allegations of sexual harassment against prominent Canadians (http://www.cbc.ca/radio/day6/here-s-a-list-of-well-known-men-in-canada-called-out-for-alleged-sexual-misconduct-since-weinstein-1.4428132). The list, including only those allegations reported by CBC, highlight the prevalence of this issue.

To prevent sexual harassment—or at least minimize its likelihood—a company should adopt a formal anti-harassment policy describing prohibited conduct, asserting its objections to the behaviour, and detailing penalties for violating the policy. Employers also have an obligation to investigate harassment complaints. Failure to enforce anti-harassment policies can be very costly. At the end of 2017, 353 women had submitted and finalized sexual harassment, discrimination or intimidation claims against the RCMP with as many as another 650 expected to file. To settle these claims, the government of Canada has set aside $100 million.

Workforce Diversity | Inclusive Workplaces

In addition to complying with equal employment opportunity laws, many companies make special efforts to recruit employees who are underrepresented in the workforce according to sex, race, or some other characteristic. In helping to build more inclusive workforces, such initiatives contribute to competitive advantage for two reasons:

- People from diverse backgrounds bring new talents and fresh perspectives to an organization, typically enhancing creativity in the development of new products.

- By more accurately reflecting the demographics of the marketplace, a diverse workforce improves a company’s ability to serve an ethnically diverse population.

Each year The Globe and Mail, reports on Canada’s Top 100 Employers (http://www.canadastop100.com/diversity/). Peruse the list of industry winners and follow through to highlights detailing why the company topped the list.

Please note the selection process:

To determine this year’s winners of the Canada’s Best Diversity Employers competition, Mediacorp editors reviewed diversity and inclusiveness initiatives at employers that applied for the Canada’s Top 100 Employers project. From this applicant pool, a smaller short-list of employers with noteworthy and unique diversity initiatives was developed. The short-listed candidates’ programs were compared to those of other employers in the same field. The finalists chosen represent the diversity leaders in their industry and region of Canada.

The Individual Approach to Ethics

How can you make sure that you do the right thing in the business world? How should you respond to the kinds of challenges that you’ll be facing? Because your actions in the business world will be strongly influenced by your moral character, let’s begin by assessing your current moral condition. Which of the following best applies to you (select one)?

- I’m always ethical.

- I’m mostly ethical.

- I’m somewhat ethical.

- I’m seldom ethical.

- I’m never ethical.

Now that you’ve placed yourself in one of these categories, here are some general observations. Few people put themselves below the second category. Most of us are ethical most of the time, and most people assign themselves to category number two— “I’m mostly ethical.” Why don’t more people claim that they’re always ethical?

Apparently, most people realize that being ethical all the time takes a great deal of moral energy. If you placed yourself in category number two, ask yourself this question: How can I change my behaviour so that I can move up a notch? The answer to this question may be simple. Just ask yourself an easier question: How would I like to be treated in a given situation?[21]

Unfortunately, practising this philosophy might be easier in your personal life than in the business world. Ethical challenges arise in business because companies, especially large ones, have multiple stakeholders who sometimes make competing demands. Making decisions that affect multiple stakeholders isn’t easy even for seasoned managers; and for new entrants to the business world, the task can be extremely daunting. You can, however, get a head start in learning how to make ethical decisions by looking at two types of challenges that you’ll encounter in the business world: ethical dilemmas and ethical decisions.

Case Study: How a Bottle Cap Restored a Reputation (Temporarily)

Case Study: How a Bottle Cap Restored a Reputation (Temporarily)

Addressing Ethical Dilemmas

An ethical dilemma is a morally problematic situation: you must choose between two or more acceptable but often opposing alternatives that are important to different groups. Experts often frame this type of situation as a “right-versus-right” decision. It’s the sort of decision that Johnson & Johnson (known as J&J) CEO James Burke had to make in 1982.[22] On September 30, twelve-year-old Mary Kellerman of Chicago died after her parents gave her Extra-Strength Tylenol. That same morning, twenty-seven-year-old Adam Janus, also of Chicago, died after taking Tylenol for minor chest pain. That night, when family members came to console his parents, Adam’s brother and his wife took Tylenol from the same bottle and died within forty-eight hours. Over the next two weeks, four more people in Chicago died after taking Tylenol. The actual connection between Tylenol and the series of deaths wasn’t made until an off-duty fireman realized from news reports that every victim had taken Tylenol. As consumers panicked, J&J pulled Tylenol off Chicago-area retail shelves. Researchers discovered Tylenol capsules containing large amounts of deadly cyanide. Because the poisoned bottles came from batches originating at different J&J plants, investigators determined that the tampering had occurred after the product had been shipped.[23]

So J&J wasn’t at fault. But CEO Burke was still faced with an extremely serious dilemma: Was it possible to respond to the tampering cases without destroying the reputation of a highly profitable brand?

Burke had two options:

- He could recall only the lots of Extra-Strength Tylenol that were found to be tainted with cyanide. In 1991, Perrier executives recalled only tainted product when they discovered that cases of their bottled water had been poisoned with benzine. This option favoured J&J financially but possibly put more people at risk.

- Burke could order a nationwide recall—of all bottles of Extra-Strength Tylenol. This option would reverse the priority of the stakeholders, putting the safety of the public above stakeholders’ financial interests.

Burke opted to recall all 31 million bottles of Extra-Strength Tylenol on the market. The cost to J&J was $100 million, but public reaction was quite positive. Less than six weeks after the crisis began, Tylenol capsules were reintroduced in new tamper-resistant bottles, and by responding quickly and appropriately, J&J was eventually able to restore the Tylenol brand to its previous market position. When Burke was applauded for moral courage, he replied that he’d simply adhered to the long-standing J&J credo that put the interests of customers above those of other stakeholders. His only regret was that the perpetrator was never caught.[24]

If you’re wondering what your thought process should be if you’re confronted with an ethical dilemma, you might wish to remember the mental steps listed here—which happen to be the steps that James Burke took in addressing the Tylenol crisis:

- Define the problem: How to respond to the tampering case without destroying the reputation of the Tylenol brand.

- Identify feasible options: (1) Recall only the lots of Tylenol that were found to be tainted or (2) order a nationwide recall of all bottles of Extra-Strength Tylenol.

- Assess the effect of each option on stakeholders: Option 1 (recalling only the tainted lots of Tylenol) is cheaper but puts more people at risk. Option 2 (recalling all bottles of Extra-Strength Tylenol) puts the safety of the public above stakeholders’ financial interests.

- Establish criteria for determining the most appropriate action: Adhere to the J&J credo, which puts the interests of customers above those of other stakeholders.

- Select the best option based on the established criteria: In 1982, Option 2 was selected, and a nationwide recall of all bottles of Extra-Strength Tylenol was conducted.

Making Ethical Decisions

In contrast to the “right-versus-right” problem posed by an ethical dilemma, an ethical decision entails a “right-versus-wrong” decision—one in which there is clearly a right (ethical) choice and a wrong (unethical or illegal) choice. When you make a decision that’s unmistakably unethical or illegal, you’ve committed an ethical lapse. If you’re presented with this type of choice, asking yourself the following questions and increase your odds of making an ethical decision.

- Is the action illegal?

- Is it unfair to some stakeholders?

- If I do it, will I feel badly about it?

- Will I be ashamed to tell my family friends, coworkers, or boss?

- Will I be embarrassed if my action is written up in the newspaper?

To test the validity of this approach, consider a point-by-point look at Trudeau’s decisions.

Here use the five-question process for ethical decision-making in Chapter 3 to determine if Trudeau made an ethical choice in his decision to vacation on the Aga Khan’s private island. You response is anonymous and will be added to responses from other institutions using this textbook chapter.

If you answer yes to any one of these five questions when considering an ethical dilemma, odds are that you’re about to do something you shouldn’t.

Revisiting Johnson & Johnson

As discussed earlier, Johnson & Johnson received tremendous praise for the actions taken by its CEO, James Burke, in response to the 1982 Tylenol catastrophe. However, things change. To learn how a company can destroy its good reputation, let’s fast forward to 2008 and revisit J&J and its credo, which states, “We believe our first responsibility is to the doctors, nurses and patients, to mothers and fathers and all others who use our products and services. In meeting their needs everything we do must be of high quality.”[25] How could a company whose employees believed so strongly in its credo find itself under criminal and congressional investigation for a series of recalls due to defective products?[26] In a three-year period, the company recalled twenty-four products, including Children’s, Infants’ and Adults’ Tylenol, Motrin, and Benadryl;[27] 1-Day Acuvue TruEye contact lenses sold outside the U.S.;[28] and hip replacements.[29]

Unlike the Tylenol recall, no one had died from the defective products, but customers were certainly upset to find they had purchased over-the-counter medicines for themselves and their children that were potentially contaminated with dark particles or tiny specks of metal;[30] contact lenses that contained a type of acid that caused stinging or pain when inserted in the eye;[31] and defective hip implants that required patients to undergo a second hip replacement.[32]

Who bears the responsibility for these image-damaging blunders? Two individuals who were at least partially responsible were William Weldon, CEO, and Colleen Goggins, Worldwide Chairman of J&J’s Consumer Group. Weldon has been criticized for being largely invisible and publicly absent during the recalls.[33] Additionally, he admitted that he did not understand the consumer division where many of the quality control problems originated.[34] Goggins was in charge of the factories that produced many of the recalled products. She was heavily criticized by fellow employees for her excessive cost-cutting measures and her propensity to replace experienced scientists with new hires.[35] In addition, she was implicated in scheme to avoid publicly disclosing another J&J recall of a defective product.

After learning that J&J had released packets of Motrin that did not dissolve correctly, the company hired contractors to go into convenience stores and secretly buy up every pack of Motrin on the shelves. The instructions given to the contractors were the following: “You should simply ‘act’ like a regular customer while making these purchases. THERE MUST BE NO MENTION OF THIS BEING A RECALL OF THE PRODUCT!”[36] In May 2010, when Goggins appeared before a congressional committee investigating the “phantom recall,” she testified that she was not aware of the behaviour of the contractors[37] and that she had “no knowledge of instructions to contractors involved in the phantom recall to not tell store employees what they were doing.” In her September 2010 testimony to the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, she acknowledged that the company in fact wrote those very instructions.

Refusing to Rationalize

Despite all the good arguments in favour of doing the right thing, why do many reasonable people act unethically (at least at times)? Why do good people make bad choices? According to one study, there are four common rationalizations (excuses) for justifying misconduct:[38]

- My behaviour isn’t really illegal or immoral. Rationalizers try to convince themselves that an action is OK if it isn’t downright illegal or blatantly immoral. They tend to operate in a gray area where there’s no clear evidence that the action is wrong.

- My action is in everyone’s best interests. Some rationalizers tell themselves: “I know I lied to make the deal, but it’ll bring in a lot of business and pay a lot of bills.” They convince themselves that they’re expected to act in a certain way.[39]

- No one will find out what I’ve done. Here, the self-questioning comes down to “If I didn’t get caught, did I really do it?” The answer is yes. There’s a simple way to avoid succumbing to this rationalization: always act as if you’re being watched.

- The company will condone my action and protect me. This justification rests on a fallacy.

If you find yourself having to rationalize a decision, it’s probably a bad one.

What to Do When the Light Turns Yellow

Like our five questions, some ethical problems are fairly straightforward. Others, unfortunately, are more complicated, but it will help to think of our five-question test as a set of signals that will warn you that you’re facing a particularly tough decision— that you should think carefully about it and perhaps consult someone else. The situation is like approaching a traffic light. Red and green lights are easy; you know what they mean and exactly what to do. Yellow lights are trickier. Before you decide which pedal to hit, try posing our five questions. If you get a single yes, you’ll almost surely be better off hitting the brake.[40]

Key Takeaways / Important Terms and Concepts

- Business ethics is the application of ethical behaviour in a business context. Ethical (trustworthy) companies are better able to attract and keep customers, talented employees, and capital.

- Acting ethically in business means more than just obeying laws and regulations. It also means being honest, doing no harm to others, competing fairly, and declining to put your own interests above those of your employer and coworkers.

- In the business world, you’ll encounter conflicts of interest: situations in which you’ll have to choose between taking action that promotes your personal interest and action that favors the interest of others.

- Corporate social responsibility refers to the approach that an organization takes in balancing its responsibilities toward different stakeholders (owners, employees, customers, and the communities in which they conduct business) when making legal, economic, ethical, and social decisions.

- Managers have several responsibilities: to increase the value of owners’ investments through profitable operations, to provide owners and other stakeholders with accurate, reliable financial information, to safeguard the company’s assets, and to handle its funds in a trustworthy manner.

- Companies have a responsibility to pay appropriate wages and benefits, treat all workers fairly, and provide equal opportunities for all employees. In addition, they must guard workers’ safety and health and to provide them with a work environment that’s free from sexual harassment.

- Consumers have certain legal rights: to use safe products, to be informed about products, to choose what to buy, and to be heard. Sellers must comply with these requirements.

- Business people face two types of ethical challenges: ethical dilemmas and ethical decisions.

- An ethical dilemma is a morally problematic situation in which you must choose competing and often conflicting options which do not satisfy all stakeholders.

- An ethical decision is one in which there’s a right (ethical) choice and a wrong (unethical or downright illegal) choice.