3 Essential Initial Research

Learning Objectives

After completing this chapter, you will be able to

- Apply analytical skills to assess how the nature of the entrepreneurial environment can influence entrepreneurial outcomes

- Apply the right tools to do impactful analyses at each of the societal, industry, market, and firm levels to evaluate entrepreneurial and other business opportunities

Overview

This chapter introduces the distinct levels of analyses that must be considered while stressing the importance of applying the appropriate tools to conduct the analyses at each level.

Support Information

It is important to conduct the essential initial research. All information and items in the plan should be backed with facts from valid primary or secondary sources. Alternatively, some entrepreneurs can make valid claims based on experience and expertise. As such, their background and experiences should be delineated to support the claims made in their business plan.

| Evidence-based claims make the business plan stronger. |

Levels of Analyses

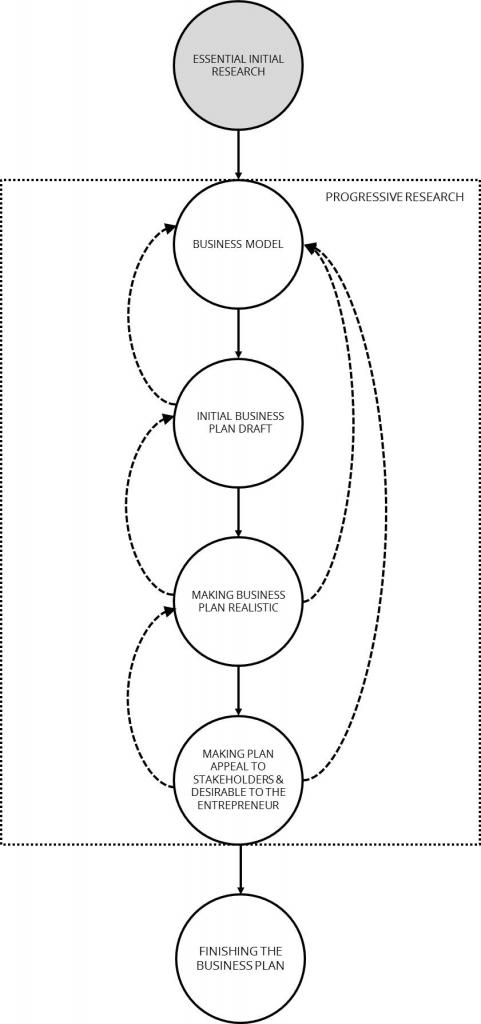

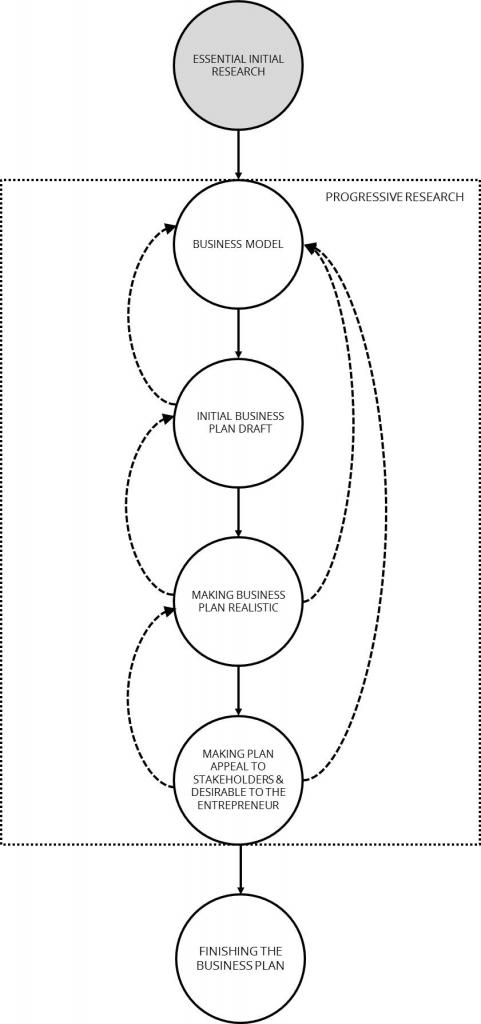

When evaluating entrepreneurial opportunities—sometimes called idea screening—an effective process involves assessing the various venture ideas being considered by applying different levels and types of analyses. Entrepreneurs starting ventures and running existing businesses should also regularly analyze their operating environments at the societal, industry, market, and firm levels. The right tools, though, must be applied at each level of analysis (see Figure 3). It is critical to complete the essential initial research at all four levels (societal, industry, market, and firm). The initial scan should be high-level, designed to assist in making key decisions (i.e. determining if there is a viable market opportunity for the venture). Secondary scans should be continuously conducted to support each part of the business plan (i.e. operations, marketing, and finance). However, information should only be included if it is research-based, relevant, and adds value to the business plan. The results from such research (i.e. the Bank of Canada indicates that interest rates will be increasing in the next two years) should support business strategies within the plan (i.e. debt financing may be less favourable than equity financing). Often, obtaining support data (i.e. construction quotes) is not immediate, so plant a flag and move forward. Valid useful resources may include information from Statistics Canada, Bank of Canada, IBIS World Report, etc.

Societal Level

At a societal level, it is important to understand each of the political, economic, social, technological, environmental, and legal (PESTEL) factors—and, more specifically, the trends affecting those factors—that will affect a venture based on a particular idea. Some venture ideas might be screened out and others might be worth pursuing at a particular time because of the trends occurring with those PESTEL factors. When including this research in your business plan, avoid using technical jargon or informal language that may distract readers (i.e. rivalry among firms) and use simpler language (i.e. competitive environment).

Industry Level

Analysis of the industry level will focus on the sector of the economy in which you intend to operate. Because the right analysis tool must be used for the assessment to be effective, apply Porter’s Five Forces Model, or a similar tool, to assess industry-level factors.[1] Again, avoid technical jargon (i.e. threat of new entrants) and use simpler wording (i.e. difficulty of entering the market) or flip to an analysis of the threat (i.e. strategies to establish and maintain market share).

Market Level

At the market level, you need to use a tool to generate information about the part of the industry in which your business will compete. This tool might be a set of questions designed to uncover information that you need to know to help develop plans to improve your proposed venture’s success.

Firm Level

At a firm level, both the internal organizational trends and the external market profile trends should be analyzed. There are several tools for conducting an internal organizational analysis, and you should normally apply many of them.

Analyzing the Trends at Each Level

Analyze Societal-Level Trends

Use an appropriate tool like the PESTEL Model to assess both the current situation and the likely changes that may affect your venture in the future:

- Political factors – federal & provincial & municipal government policy, nature of political decisions, potential political changes, infrastructure plans, etc.

- Economic factors – interest rates, inflation rates, exchange rates, tax rates, GDP growth, health of the economy, etc.

- Social factors – population characteristics like age distribution and education levels, changes in demand for types of products and services, etc.

- Technological factors – new processes, new products, infrastructure, etc.

- Environmental factors – effects of climate / weather, water availability, smog and pollution issues, etc.

- Legal factors – labour laws, minimum wage rates, liability issues, etc.

After assessing these factors, analyze the impact these trends have upon the venture:

- Do the trends uncover opportunities and threats?

- Can opportunities be capitalized on?

- Can problems be mitigated?

- Can the venture be sustained?

Analyze Industry-Level Trends

Use an appropriate tool like the Five Forces Model to analyze the industry in which you expect to operate:

- Horizontal relationships – threat of substitutes, rivalry among existing competitors, threat of new entrants, etc.

- Vertical Relationships – bargaining power of buyers, bargaining power of suppliers, etc.

Analyze Market-Level Trends

Use an appropriate method like a market profile analysis to assess the position within the industry in which you expect to operate. To do so, determine the answers to questions like the following:

- How attractive is the market?

- In what way are competitors expected to respond if you enter the market?

- What is the current size of the market and how large is it expected to become?

- What are the current and projected growth rates?

- At what stage of the development cycle is the market?

- What level of profits can be expected in the market?

- What proportion of the market can be captured? What will be the cost to capture this proportion and what is the cost to capture the proportion required for business sustainability?

Prior to a new business start-up, the customers that the new business wishes to attract either already purchase the product or service from a competitor to the new business—or do not yet purchase the product or service at all. A new venture’s customers, therefore, must come from one of two sources. They must be attracted away from existing (direct) competitors or be convinced to make different choices about where they spend their money so they purchase the new venture’s product or service instead of spending their money in other ways (with indirect competitors). This means an entrepreneur must decide from which source they will attract their customers, and how they will do so. They must understand the competitive environment.

According to Porter, strategy is about doing different things than competitors or doing similar things but in different ways.[2] In order to develop an effective strategy, an entrepreneur must understand the competition.

To understanding the competitive environment, entrepreneurs must do the following:

- Determine who their current direct and indirect competitors are and who the future competitors may be

- Understand the similarities and differences in quality, price, competitive advantages, and other factors that exist between their proposed business and the existing competitors

- Establish whether they can offer different products or services—or the same products or services in different ways—to attract enough customers to meet their goals

- Anticipate how the competitors will react in response to the new venture’s entry into the market

Analyze Firm-Level Trends (organizational analysis)

There are several tools available for firm-level analysis, and usually several of them should be applied because they serve different purposes.

Tools like a SWOT Analysis or TOWS Matrix can formulate and evaluate potential strategies to leverage organizational strengths, overcome/minimize weaknesses, take advantage of opportunities, and overcome/minimize threats. You will also need to do a financial analysis and consider the founder fit and the competencies a venture should possess.

- SWOT Analysis – identify organizational strengths and weaknesses and external opportunities and threats

- TOWS Matrix – develop strategies to

- Leverage strengths to take advantage of opportunities

- Leverage strengths to overcome threats

- Mitigate weaknesses by taking advantage of opportunities

- Mitigate weaknesses while minimizing the potential threats or the potential outcomes from threats

To analyze a firm’s strategy, apply a VRIO Framework analysis, as Barney and Barney and Hesterly outline.[3][4] While conceptualizing the resource-based view (RBV) of a firm, they identified the following four considerations regarding resources and their ability to help a firm gain a competitive advantage. Together, the following four questions make up the VRIO Framework, which can assess a firm’s capacity and determine what competencies a venture should have. To use this tool, you need to determine whether competencies are valuable, rare, inimitable, and organized in a way that they can be exploited:

- Value – Is a particular resource (financial, physical, technological, organizational, human, reputational, innovative) valuable to a firm because it helps it take advantage of opportunities or eliminate threats?

- Rarity – Is a particular resource rare in that it is controlled by or available to relatively few others?

- Imitability – Is a particular resource difficult to imitate so that those who have it can retain cost advantages over those who might try to obtain or duplicate it?

- Organization – Are the resources available to a firm useful to it because it is organized and ready to exploit them?

To assess the financial attractiveness of the venture, analyze

- Similar firms in industry

- Comparative ratio and financial analysis can help determine industry norm returns, turnover ratios, working capital, operating efficiency, and other measures of firm success.[5]

- Projected market share

- Analyzes the key industry players’ relative market share, and make judgments about how the proposed venture would fare within the industry.

- Uses information from market profile analysis and key industry player analysis.

- Margin analysis

- Involves projecting expected margins from venture

- Useful information might come from financial analysis, market profile analysis, and NAICS (North American Industry Classification System) codes (six digit codes used to identify an industry—first five digits are standardized in Canada, the United States, and Mexico—is gradually replacing the four digit SIC [Standard Industrial Classification] codes)

- Break-even analysis

- Involves using information from margin analysis to determine break-even volume and break even sales in dollars

- Is there sufficient volume to sustain the venture?

- Pro forma analysis

- Forecasts income and assets required to generate profits

- Sensitivity analysis

- What will be the likely impact if some assumed variable values change?

- Return on investment (ROI) projections

- Projects the ROI from undertaking the venture

- What is the opportunity cost of undertaking the venture?

Founder fit is an important consideration for entrepreneurs screening venture opportunities. While there are plenty of examples of entrepreneurs successfully starting all types of businesses, “technical capability can be an important if not all-important factor in pursuing ventures success”.[6] Factors such as the experience, training, credentials, reputation, and social capital an entrepreneur has can play an important role in their success or failure in starting a new venture. Even when an entrepreneur can recruit expert help through business partners or employees, it might be important that he or she also possess technical skills required in that particular kind of business.

- A common and useful way to help screen venture options is to seek input from experts, peers, mentors, business associates, and perhaps other stakeholders like potential customers and direct family members.

| Completing a TOWS Matrix develops strategies from the SWOT Analysis and strengthens your business plan.

Reference your technical skill, as this is a major factor in your venture’s success. |

Lean Startup[7]

Ries defines a lean start-up as “a human institution designed to create a new product or service under conditions of extreme uncertainty”. The lean-start-up approach involves releasing a minimal viable product to customers with the expectation that this early prototype will change and evolve frequently and quickly in response to customer feedback. This is meant to be a relatively easy and inexpensive way to develop a product or service by relying on customer feedback to guide the pivots in new directions that will ultimately—and relatively quickly—lead to a product or service with the appeal required for business success. It is only then that the actual business will truly emerge. As such, entrepreneurs that apply the lean-start-up approach—because their business idea allows for it—actually forgo developing a business plan, at least until they might need one later to get financing, because introducing a minimum viable product helps “entrepreneurs start the process of learning as quickly as possible”. This is followed by ever improving versions of their products or services. However, all entrepreneurs must directly consult with their potential target purchasers and end users to assess if and how the market might respond to their proposed venture. The Essential Initial Research and Progressive Research stages should include purposeful and meaningful interactions between the entrepreneur and the target purchasers and end users.

Ries’s five lean-start-up principles start with the idea that entrepreneurs are everywhere and that anyone working in an environment where they seek to create new products or services “under conditions of extreme uncertainty” can use the lean-start-up approach. Second, a start-up is more than the product or service: it is an institution that must be managed in a new way that promotes growth through innovation. Third, start-ups are about learning “how to build a sustainable business” by validating product or service design through frequent prototyping that allows entrepreneurs to test the concepts. Forth, start-ups must follow this process or feedback loop: create products and services; measure how the market reacts to them; and learn from that to determine whether to pivot or to persevere with an outcome the market accepts. Finally, Ries suggested that entrepreneurial outcomes and innovation initiatives need to be measured through innovative accounting.

Chapter Summary

By applying the right tools to analyze the operating environment at each of the societal, industry, market, and firm levels, entrepreneurs screen venture ideas, plan new venture development, and potentially detect factors that might affect their business operations. The lean start-up is an alternative that can be used to circumvent the usual planning steps in favour of continuous innovation. See Figure 4 for other resources on business models and lean start-ups.

- Porter, M. E. (1985). Competitive advantage: Creating and sustaining superior performance. Free Press. ↵

- Porter, M. E. (1996). What is strategy? Harvard Business Review, 74(6), 61-78. ↵

- Barney, J. B. (1997). Gaining and sustaining competitive advantage. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. ↵

- Barney, J. B., & Hesterly, W. S. (2006). Strategic management and competitive advantage: Concepts and cases. Pearson/Prentice Hall. ↵

- Vesper, K. H. (1996). New venture experience (revised ed.). Vector Books. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ries, E. (2011). The lean startup: How today’s entrepreneurs use continuous innovation to create radically successful businesses. Crown Business. ↵