14.5 Transport of Gases in Human Bodily Fluids

Mary Ann Clark; Jung Choi; and Matthew Douglas

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to do the following:

- Describe how oxygen is bound to hemoglobin and transported to body tissues

- Explain how carbon dioxide is transported from body tissues to the lungs

Once the oxygen diffuses across the alveoli, it enters the bloodstream and is transported to the tissues where it is unloaded, and carbon dioxide diffuses out of the blood and into the alveoli to be expelled from the body. Although gas exchange is a continuous process, the oxygen and carbon dioxide are transported by different mechanisms.

Transport of Oxygen in the Blood

Although oxygen dissolves in blood, only a small amount of oxygen is transported this way. Only 1.5 percent of oxygen in the blood is dissolved directly into the blood itself. Most oxygen—98.5 percent—is bound to a protein called hemoglobin and carried to the tissues.

Hemoglobin

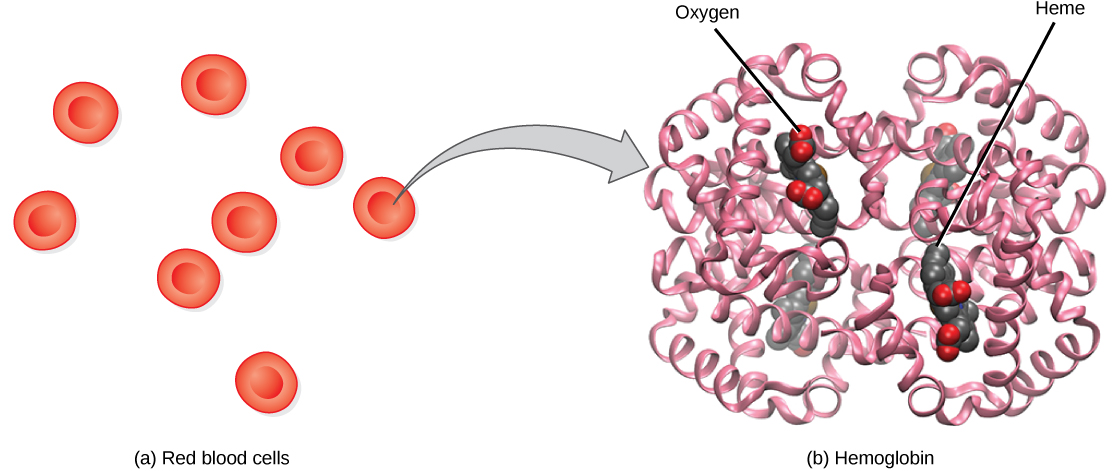

Hemoglobin, or Hb, is a protein molecule found in red blood cells (erythrocytes) made of four subunits: two alpha subunits and two beta subunits (Figure 14.19). Each subunit surrounds a central heme group that contains iron and binds one oxygen molecule, allowing each hemoglobin molecule to bind four oxygen molecules. Molecules with more oxygen bound to the heme groups are brighter red. As a result, oxygenated arterial blood where the Hb is carrying four oxygen molecules is bright red, while venous blood that is deoxygenated is darker red.

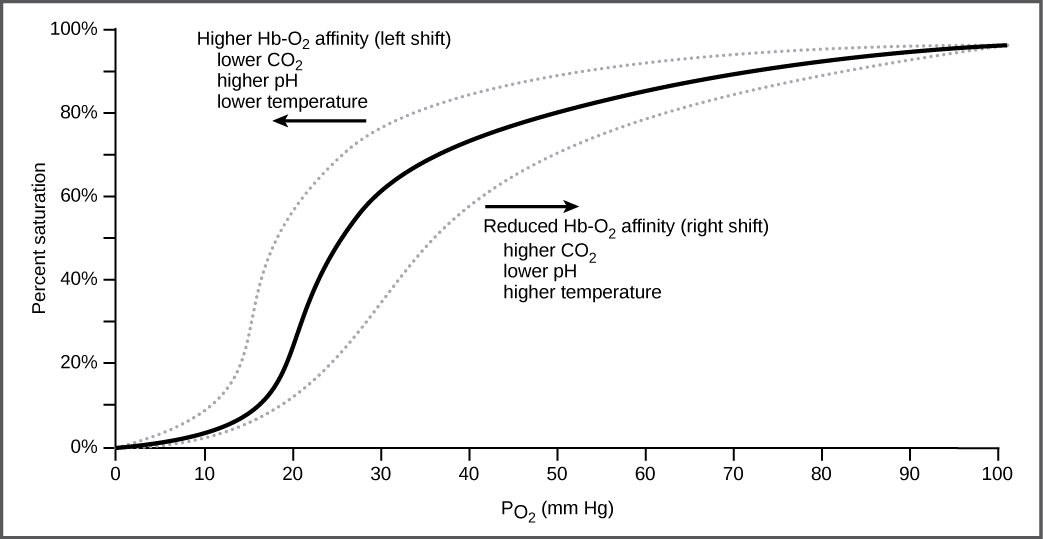

It is easier to bind a second and third oxygen molecule to Hb than the first molecule. This is because the hemoglobin molecule changes its shape, or conformation, as oxygen binds. The fourth oxygen is then more difficult to bind. The binding of oxygen to hemoglobin can be plotted as a function of the partial pressure of oxygen in the blood (x-axis) versus the relative Hb-oxygen saturation (y-axis). The resulting graph—an oxygen dissociation curve—is sigmoidal, or S-shaped (Figure 14.20). As the partial pressure of oxygen increases, the hemoglobin becomes increasingly saturated with oxygen.

Visual Connection

The kidneys are responsible for removing excess H+ ions from the blood. If the kidneys fail, what would happen to blood pH and to hemoglobin affinity for oxygen?

Factors That Affect Oxygen Binding

The oxygen-carrying capacity of hemoglobin determines how much oxygen is carried in the blood. In addition to ![]() , other environmental factors and diseases can affect oxygen carrying capacity and delivery.

, other environmental factors and diseases can affect oxygen carrying capacity and delivery.

Carbon dioxide levels, blood pH, and body temperature affect oxygen-carrying capacity (Figure 14.20). When carbon dioxide is in the blood, it reacts with water to form bicarbonate ![]()

and hydrogen ions (H+). As the level of carbon dioxide in the blood increases, more H+ is produced and the pH decreases. This increase in carbon dioxide and subsequent decrease in pH reduce the affinity of hemoglobin for oxygen. The oxygen dissociates from the Hb molecule, shifting the oxygen dissociation curve to the right. Therefore, more oxygen is needed to reach the same hemoglobin saturation level as when the pH was higher. A similar shift in the curve also results from an increase in body temperature. Increased temperature, such as from increased activity of skeletal muscle, causes the affinity of hemoglobin for oxygen to be reduced.

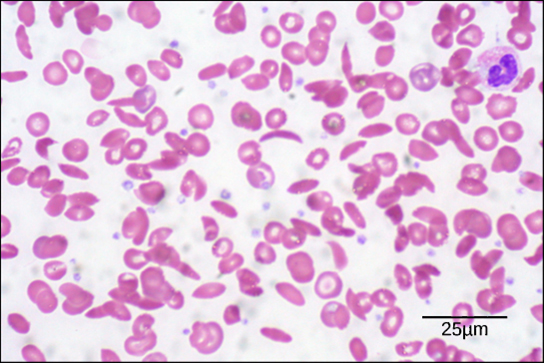

Diseases like sickle cell anemia and thalassemia decrease the blood’s ability to deliver oxygen to tissues and its oxygen-carrying capacity. In sickle cell anemia, the shape of the red blood cell is crescent-shaped, elongated, and stiffened, reducing its ability to deliver oxygen (Figure 14.21). In this form, red blood cells cannot pass through the capillaries. This is painful when it occurs. Thalassemia is a rare genetic disease caused by a defect in either the alpha or the beta subunit of Hb. Patients with thalassemia produce a high number of red blood cells, but these cells have lower-than-normal levels of hemoglobin. Therefore, the oxygen-carrying capacity is diminished.

Transport of Carbon Dioxide in the Blood

Carbon dioxide molecules are transported in the blood from body tissues to the lungs by one of three methods: dissolution directly into the blood, binding to hemoglobin, or carried as a bicarbonate ion. Several properties of carbon dioxide in the blood affect its transport. First, carbon dioxide is more soluble in blood than oxygen. About 5 to 7 percent of all carbon dioxide is dissolved in the plasma. Second, carbon dioxide can bind to plasma proteins or can enter red blood cells and bind to hemoglobin. This form transports about 10 percent of the carbon dioxide. When carbon dioxide binds to hemoglobin, a molecule called carbaminohemoglobin is formed. Binding of carbon dioxide to hemoglobin is reversible. Therefore, when it reaches the lungs, the carbon dioxide can freely dissociate from the hemoglobin and be expelled from the body.

Third, the majority of carbon dioxide molecules (85 percent) are carried as part of the bicarbonate buffer system. In this system, carbon dioxide diffuses into the red blood cells. Carbonic anhydrase (CA) within the red blood cells quickly converts the carbon dioxide into carbonic acid (H2CO3). Carbonic acid is an unstable intermediate molecule that immediately dissociates into bicarbonate ions ![]() and hydrogen (H+) ions. Since carbon dioxide is quickly converted into bicarbonate ions, this reaction allows for the continued uptake of carbon dioxide into the blood down its concentration gradient. It also results in the production of H+ ions. If too much H+ is produced, it can alter blood pH. However, hemoglobin binds to the free H+ ions and thus limits shifts in pH. The newly synthesized bicarbonate ion is transported out of the red blood cell into the liquid component of the blood in exchange for a chloride ion (Cl–); this is called the chloride shift. When the blood reaches the lungs, the bicarbonate ion is transported back into the red blood cell in exchange for the chloride ion. The H+ ion dissociates from the hemoglobin and binds to the bicarbonate ion. This produces the carbonic acid intermediate, which is converted back into carbon dioxide through the enzymatic action of CA. The carbon dioxide produced is expelled through the lungs during exhalation.

and hydrogen (H+) ions. Since carbon dioxide is quickly converted into bicarbonate ions, this reaction allows for the continued uptake of carbon dioxide into the blood down its concentration gradient. It also results in the production of H+ ions. If too much H+ is produced, it can alter blood pH. However, hemoglobin binds to the free H+ ions and thus limits shifts in pH. The newly synthesized bicarbonate ion is transported out of the red blood cell into the liquid component of the blood in exchange for a chloride ion (Cl–); this is called the chloride shift. When the blood reaches the lungs, the bicarbonate ion is transported back into the red blood cell in exchange for the chloride ion. The H+ ion dissociates from the hemoglobin and binds to the bicarbonate ion. This produces the carbonic acid intermediate, which is converted back into carbon dioxide through the enzymatic action of CA. The carbon dioxide produced is expelled through the lungs during exhalation.

The benefit of the bicarbonate buffer system is that carbon dioxide is “soaked up” into the blood with little change to the pH of the system. This is important because it takes only a small change in the overall pH of the body for severe injury or death to result. The presence of this bicarbonate buffer system also allows for people to travel and live at high altitudes: When the partial pressure of oxygen and carbon dioxide change at high altitudes, the bicarbonate buffer system adjusts to regulate carbon dioxide while maintaining the correct pH in the body.

Carbon Monoxide Poisoning

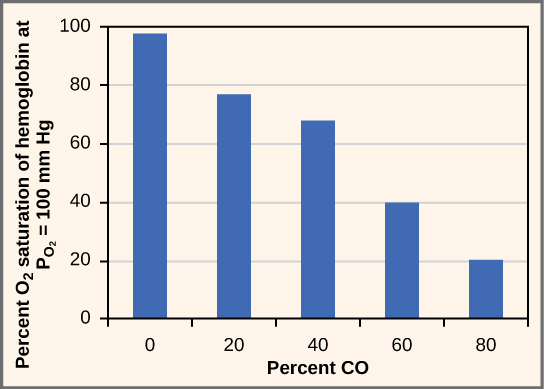

While carbon dioxide can readily associate and dissociate from hemoglobin, other molecules such as carbon monoxide (CO) cannot. Carbon monoxide has a greater affinity for hemoglobin than oxygen. Therefore, when carbon monoxide is present, it binds to hemoglobin preferentially over oxygen. As a result, oxygen cannot bind to hemoglobin, so very little oxygen is transported through the body (Figure 14.22). Carbon monoxide is a colorless, odorless gas and is therefore difficult to detect. It is produced by gas-powered vehicles and tools. Carbon monoxide can cause headaches, confusion, and nausea; long-term exposure can cause brain damage or death. Administering 100 percent (pure) oxygen is the usual treatment for carbon monoxide poisoning. Administration of pure oxygen speeds up the separation of carbon monoxide from hemoglobin.

Section Summary

Hemoglobin is a protein found in red blood cells that is comprised of two alpha and two beta subunits that surround an iron-containing heme group. Oxygen readily binds this heme group. The ability of oxygen to bind increases as more oxygen molecules are bound to heme. Disease states and altered conditions in the body can affect the binding ability of oxygen, and increase or decrease its ability to dissociate from hemoglobin.

Carbon dioxide can be transported through the blood via three methods. It is dissolved directly in the blood, bound to plasma proteins or hemoglobin, or converted into bicarbonate. The majority of carbon dioxide is transported as part of the bicarbonate system. Carbon dioxide diffuses into red blood cells. Inside, carbonic anhydrase converts carbon dioxide into carbonic acid (H2CO3), which is subsequently hydrolyzed into bicarbonate ![]() and H+. The H+ ion binds to hemoglobin in red blood cells, and bicarbonate is transported out of the red blood cells in exchange for a chloride ion. This is called the chloride shift. Bicarbonate leaves the red blood cells and enters the blood plasma. In the lungs, bicarbonate is transported back into the red blood cells in exchange for chloride. The H+ dissociates from hemoglobin and combines with bicarbonate to form carbonic acid with the help of carbonic anhydrase, which further catalyzes the reaction to convert carbonic acid back into carbon dioxide and water. The carbon dioxide is then expelled from the lungs.

and H+. The H+ ion binds to hemoglobin in red blood cells, and bicarbonate is transported out of the red blood cells in exchange for a chloride ion. This is called the chloride shift. Bicarbonate leaves the red blood cells and enters the blood plasma. In the lungs, bicarbonate is transported back into the red blood cells in exchange for chloride. The H+ dissociates from hemoglobin and combines with bicarbonate to form carbonic acid with the help of carbonic anhydrase, which further catalyzes the reaction to convert carbonic acid back into carbon dioxide and water. The carbon dioxide is then expelled from the lungs.

Exercises

Visual Connection Questions

Figure 39.20: The kidneys are responsible for removing excess H+ ions from the blood. If the kidneys fail, what would happen to blood pH and to hemoglobin affinity for oxygen?

Review Questions

Which of the following will NOT facilitate the transfer of oxygen to tissues?

- decreased body temperature

- decreased pH of the blood

- increased carbon dioxide

- increased exercise

The majority of carbon dioxide in the blood is transported by ________.

- binding to hemoglobin

- dissolution in the blood

- conversion to bicarbonate

- binding to plasma proteins

The majority of oxygen in the blood is transported by ________.

- dissolution in the blood

- being carried as bicarbonate ions

- binding to blood plasma

- binding to hemoglobin

Critical Thinking Questions

- What would happen if no carbonic anhydrase were present in red blood cells?

- How does the administration of 100 percent oxygen save a patient from carbon monoxide poisoning? Why wouldn’t giving carbon dioxide work?

Glossary

- bicarbonate buffer system

- system in the blood that absorbs carbon dioxide and regulates pH levels

- bicarbonate

ion

ion - ion created when carbonic acid dissociates into H+ and

- carbaminohemoglobin

- molecule that forms when carbon dioxide binds to hemoglobin

- carbonic anhydrase (CA)

- enzyme that catalyzes carbon dioxide and water into carbonic acid

- chloride shift

- exchange of chloride for bicarbonate into or out of the red blood cell

- heme group

- centralized iron-containing group that is surrounded by the alpha and beta subunits of hemoglobin

- hemoglobin

- molecule in red blood cells that can bind oxygen, carbon dioxide, and carbon monoxide

- oxygen-carrying capacity

- amount of oxygen that can be transported in the blood

- oxygen dissociation curve

- curve depicting the affinity of oxygen for hemoglobin

- sickle cell anemia

- genetic disorder that affects the shape of red blood cells, and their ability to transport oxygen and move through capillaries

- thalassemia

- rare genetic disorder that results in mutation of the alpha or beta subunits of hemoglobin, creating smaller red blood cells with less hemoglobin

Chapter 39 in OpenStax Concepts of Biology 2e