Chapter 5: Introduction to Reproduction at the Cellular Level

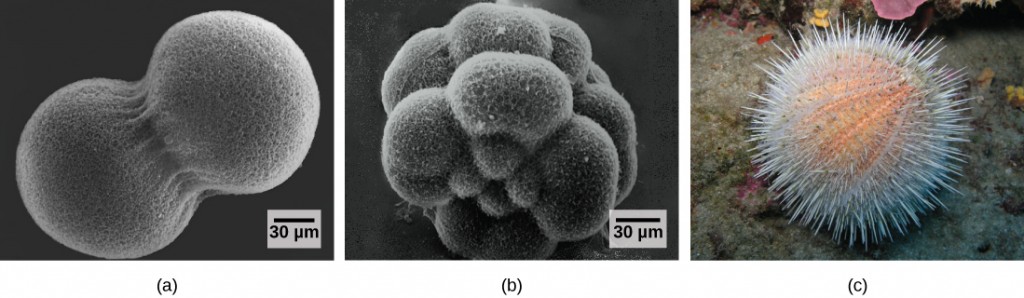

The individual sexually reproducing organism—including humans—begins life as a fertilized egg, or zygote. Trillions of cell divisions subsequently occur in a controlled manner to produce a complex, multicellular human. In other words, that original single cell was the ancestor of every other cell in the body. Once a human individual is fully grown, cell reproduction is still necessary to repair or regenerate tissues. For example, new blood and skin cells are constantly being produced. All multicellular organisms use cell division for growth, and in most cases, the maintenance and repair of cells and tissues. Single-celled organisms use cell division as their method of reproduction.