3.5 Passive Transport

Charles Molnar and Jane Gair

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain why and how passive transport occurs

- Understand the processes of osmosis and diffusion

- Define tonicity and describe its relevance to passive transport

Plasma membranes must allow certain substances to enter and leave a cell, while preventing harmful material from entering and essential material from leaving. In other words, plasma membranes are selectively permeable—they allow some substances through but not others. If they were to lose this selectivity, the cell would no longer be able to sustain itself, and it would be destroyed. Some cells require larger amounts of specific substances than do other cells; they must have a way of obtaining these materials from the extracellular fluids. This may happen passively, as certain materials move back and forth, or the cell may have special mechanisms that ensure transport. Most cells expend most of their energy, in the form of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), to create and maintain an uneven distribution of ions on the opposite sides of their membranes. The structure of the plasma membrane contributes to these functions, but it also presents some problems.

The most direct forms of membrane transport are passive. Passive transport is a naturally occurring phenomenon and does not require the cell to expend energy to accomplish the movement. In passive transport, substances move from an area of higher concentration to an area of lower concentration in a process called diffusion. A physical space in which there is a different concentration of a single substance is said to have a concentration gradient.

Selective Permeability

Plasma membranes are asymmetric, meaning that despite the mirror image formed by the phospholipids, the interior of the membrane is not identical to the exterior of the membrane. Integral proteins that act as channels or pumps work in one direction. Carbohydrates, attached to lipids or proteins, are also found on the exterior surface of the plasma membrane. These carbohydrate complexes help the cell bind substances that the cell needs in the extracellular fluid. This adds considerably to the selective nature of plasma membranes.

Recall that plasma membranes have hydrophilic and hydrophobic regions. This characteristic helps the movement of certain materials through the membrane and hinders the movement of others. Lipid-soluble material can easily slip through the hydrophobic lipid core of the membrane. Substances such as the fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E, and K readily pass through the plasma membranes in the digestive tract and other tissues. Fat-soluble drugs also gain easy entry into cells and are readily transported into the body’s tissues and organs. Molecules of oxygen and carbon dioxide have no charge and pass through by simple diffusion.

Polar substances, with the exception of water, present problems for the membrane. While some polar molecules connect easily with the outside of a cell, they cannot readily pass through the lipid core of the plasma membrane. Additionally, whereas small ions could easily slip through the spaces in the mosaic of the membrane, their charge prevents them from doing so. Ions such as sodium, potassium, calcium, and chloride must have a special means of penetrating plasma membranes. Simple sugars and amino acids also need help with transport across plasma membranes.

Diffusion

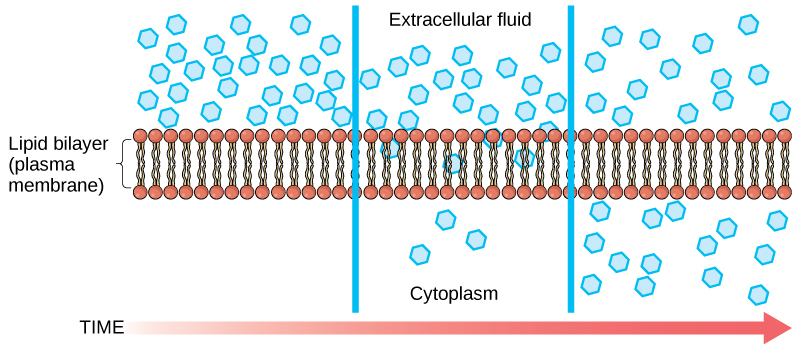

Diffusion is a passive process of transport. A single substance tends to move from an area of high concentration to an area of low concentration until the concentration is equal across the space. You are familiar with diffusion of substances through the air. For example, think about someone opening a bottle of perfume in a room filled with people. The perfume is at its highest concentration in the bottle and is at its lowest at the edges of the room. The perfume vapor will diffuse, or spread away, from the bottle, and gradually, more and more people will smell the perfume as it spreads. Materials move within the cell’s cytosol by diffusion, and certain materials move through the plasma membrane by diffusion (Figure 3.24). Diffusion expends no energy. Rather the different concentrations of materials in different areas are a form of potential energy, and diffusion is the dissipation of that potential energy as materials move down their concentration gradients, from high to low.

Each separate substance in a medium, such as the extracellular fluid, has its own concentration gradient, independent of the concentration gradients of other materials. Additionally, each substance will diffuse according to that gradient.

Several factors affect the rate of diffusion.

- Extent of the concentration gradient: The greater the difference in concentration, the more rapid the diffusion. The closer the distribution of the material gets to equilibrium, the slower the rate of diffusion becomes.

- Mass of the molecules diffusing: More massive molecules move more slowly, because it is more difficult for them to move between the molecules of the substance they are moving through; therefore, they diffuse more slowly.

- Temperature: Higher temperatures increase the energy and therefore the movement of the molecules, increasing the rate of diffusion.

- Solvent density: As the density of the solvent increases, the rate of diffusion decreases. The molecules slow down because they have a more difficult time getting through the denser medium.

Concept in Action

For an animation of the diffusion process in action, view this short video on cell membrane transport.

Facilitated transport

In facilitated transport, also called facilitated diffusion, material moves across the plasma membrane with the assistance of transmembrane proteins down a concentration gradient (from high to low concentration) without the expenditure of cellular energy. However, the substances that undergo facilitated transport would otherwise not diffuse easily or quickly across the plasma membrane. The solution to moving polar substances and other substances across the plasma membrane rests in the proteins that span its surface. The material being transported is first attached to protein or glycoprotein receptors on the exterior surface of the plasma membrane. This allows the material that is needed by the cell to be removed from the extracellular fluid. The substances are then passed to specific integral proteins that facilitate their passage, because they form channels or pores that allow certain substances to pass through the membrane. The integral proteins involved in facilitated transport are collectively referred to as transport proteins, and they function as either channels for the material or carriers.

Osmosis

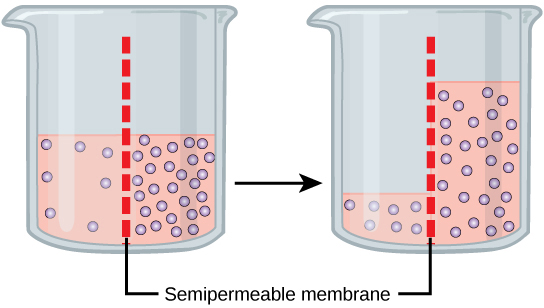

Osmosis is the diffusion of water through a semipermeable membrane according to the concentration gradient of water across the membrane. Whereas diffusion transports material across membranes and within cells, osmosis transports only water across a membrane and the membrane limits the diffusion of solutes in the water. Osmosis is a special case of diffusion. Water, like other substances, moves from an area of higher concentration to one of lower concentration. Imagine a beaker with a semipermeable membrane, separating the two sides or halves (Figure 3.25). On both sides of the membrane, the water level is the same, but there are different concentrations on each side of a dissolved substance, or solute, that cannot cross the membrane. If the volume of the water is the same, but the concentrations of solute are different, then there are also different concentrations of water, the solvent, on either side of the membrane.

A principle of diffusion is that the molecules move around and will spread evenly throughout the medium if they can. However, only the material capable of getting through the membrane will diffuse through it. In this example, the solute cannot diffuse through the membrane, but the water can. Water has a concentration gradient in this system. Therefore, water will diffuse down its concentration gradient, crossing the membrane to the side where it is less concentrated. This diffusion of water through the membrane—osmosis—will continue until the concentration gradient of water goes to zero. Osmosis proceeds constantly in living systems.

Tonicity

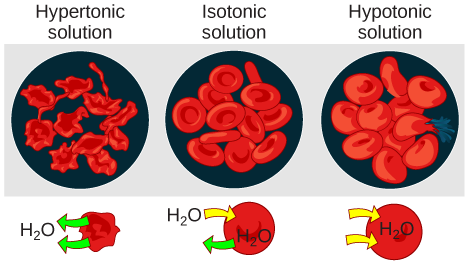

Tonicity describes the amount of solute in a solution. The measure of the tonicity of a solution, or the total amount of solutes dissolved in a specific amount of solution, is called its osmolarity. Three terms—hypotonic, isotonic, and hypertonic—are used to relate the osmolarity of a cell to the osmolarity of the extracellular fluid that contains the cells. In a hypotonic solution, such as tap water, the extracellular fluid has a lower concentration of solutes than the fluid inside the cell, and water enters the cell. (In living systems, the point of reference is always the cytoplasm, so the prefix hypo– means that the extracellular fluid has a lower concentration of solutes, or a lower osmolarity, than the cell cytoplasm.) It also means that the extracellular fluid has a higher concentration of water than does the cell. In this situation, water will follow its concentration gradient and enter the cell. This may cause an animal cell to burst, or lyse.

In a hypertonic solution (the prefix hyper– refers to the extracellular fluid having a higher concentration of solutes than the cell’s cytoplasm), the fluid contains less water than the cell does, such as seawater. Because the cell has a lower concentration of solutes, the water will leave the cell. In effect, the solute is drawing the water out of the cell. This may cause an animal cell to shrivel, or crenate.

In an isotonic solution, the extracellular fluid has the same osmolarity as the cell. If the concentration of solutes of the cell matches that of the extracellular fluid, there will be no net movement of water into or out of the cell. Blood cells in hypertonic, isotonic, and hypotonic solutions take on characteristic appearances (Figure 3.26).

A doctor injects a patient with what the doctor thinks is isotonic saline solution. The patient dies, and autopsy reveals that many red blood cells have been destroyed. Do you think the solution the doctor injected was really isotonic?

<!– No, it must have been hypotonic, as a hypotonic solution would cause water to enter the cells, thereby making them burst. –>

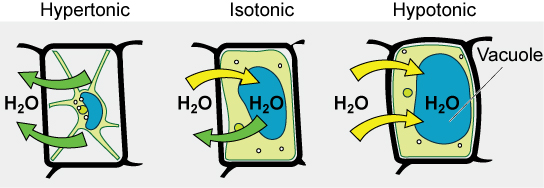

Some organisms, such as plants, fungi, bacteria, and some protists, have cell walls that surround the plasma membrane and prevent cell lysis. The plasma membrane can only expand to the limit of the cell wall, so the cell will not lyse. In fact, the cytoplasm in plants is always slightly hypertonic compared to the cellular environment, and water will always enter a cell if water is available. This influx of water produces turgor pressure, which stiffens the cell walls of the plant (Figure 3.27). In nonwoody plants, turgor pressure supports the plant. If the plant cells become hypertonic, as occurs in drought or if a plant is not watered adequately, water will leave the cell. Plants lose turgor pressure in this condition and wilt.

Section Summary

The passive forms of transport, diffusion and osmosis, move material of small molecular weight. Substances diffuse from areas of high concentration to areas of low concentration, and this process continues until the substance is evenly distributed in a system. In solutions of more than one substance, each type of molecule diffuses according to its own concentration gradient. Many factors can affect the rate of diffusion, including concentration gradient, the sizes of the particles that are diffusing, and the temperature of the system.

In living systems, diffusion of substances into and out of cells is mediated by the plasma membrane. Some materials diffuse readily through the membrane, but others are hindered, and their passage is only made possible by protein channels and carriers. The chemistry of living things occurs in aqueous solutions, and balancing the concentrations of those solutions is an ongoing problem. In living systems, diffusion of some substances would be slow or difficult without membrane proteins.

Exercises

Glossary

concentration gradient: an area of high concentration across from an area of low concentration

diffusion: a passive process of transport of low-molecular weight material down its concentration gradient

facilitated transport: a process by which material moves down a concentration gradient (from high to low concentration) using integral membrane proteins

hypertonic: describes a solution in which extracellular fluid has higher osmolarity than the fluid inside the cell

hypotonic: describes a solution in which extracellular fluid has lower osmolarity than the fluid inside the cell

isotonic: describes a solution in which the extracellular fluid has the same osmolarity as the fluid inside the cell

osmolarity: the total amount of substances dissolved in a specific amount of solution

osmosis: the transport of water through a semipermeable membrane from an area of high water concentration to an area of low water concentration across a membrane

passive transport: a method of transporting material that does not require energy

selectively permeable: the characteristic of a membrane that allows some substances through but not others

solute: a substance dissolved in another to form a solution

tonicity: the amount of solute in a solution.

Media Attributions

- Figure 3.24: modification of work by Mariana Ruiz Villarreal

- Figure 3.26: modification of work by Mariana Ruiz Villarreal

- Figure 3.27: modification of work by Mariana Ruiz Villarreal