14.3 Gas Exchange across Respiratory Surfaces

Mary Ann Clark; Jung Choi; and Matthew Douglas

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to do the following:

- Name and describe lung volumes and capacities

- Understand how gas pressure influences how gases move into and out of the body

The structure of the lung maximizes its surface area to increase gas diffusion. Because of the enormous number of alveoli (approximately 300 million in each human lung), the surface area of the lung is very large (75 m2). Having such a large surface area increases the amount of gas that can diffuse into and out of the lungs.

Basic Principles of Gas Exchange

Gas exchange during respiration occurs primarily through diffusion. Diffusion is a process in which transport is driven by a concentration gradient. Gas molecules move from a region of high concentration to a region of low concentration. Blood that is low in oxygen concentration and high in carbon dioxide concentration undergoes gas exchange with air in the lungs. The air in the lungs has a higher concentration of oxygen than that of oxygen-depleted blood and a lower concentration of carbon dioxide. This concentration gradient allows for gas exchange during respiration.

Partial pressure is a measure of the concentration of the individual components in a mixture of gases. The total pressure exerted by the mixture is the sum of the partial pressures of the components in the mixture. The rate of diffusion of a gas is proportional to its partial pressure within the total gas mixture. This concept is discussed further in detail below.

Lung Volumes and Capacities

Different animals have different lung capacities based on their activities. Cheetahs have evolved a much higher lung capacity than humans; it helps provide oxygen to all the muscles in the body and allows them to run very fast. Elephants also have a high lung capacity. In this case, it is not because they run fast but because they have a large body and must be able to take up oxygen in accordance with their body size.

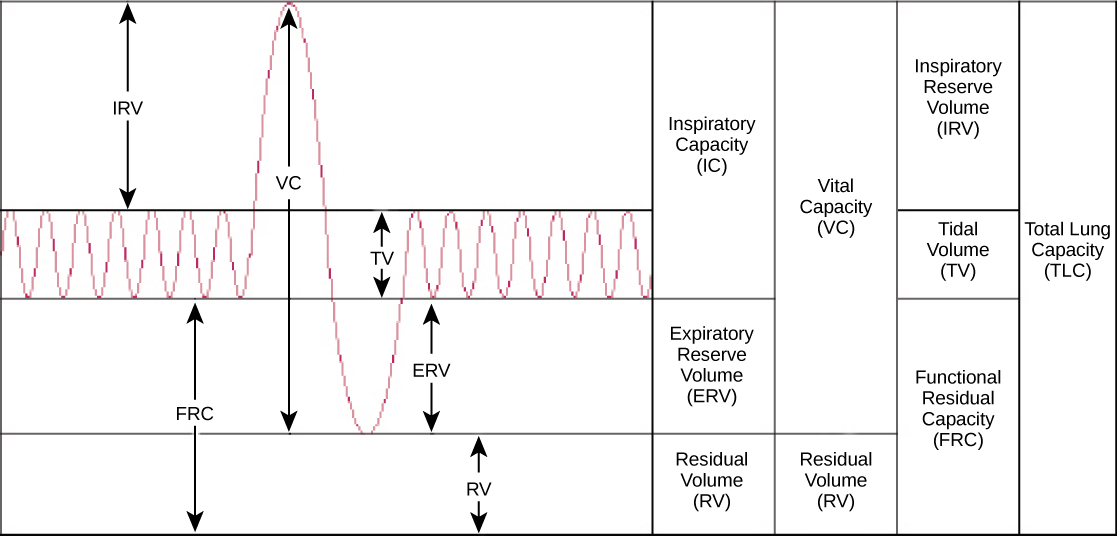

Human lung size is determined by genetics, sex, and height. At maximal capacity, an average lung can hold almost six liters of air, but lungs do not usually operate at maximal capacity. Air in the lungs is measured in terms of lung volumes and lung capacities (Figure 14.12) and (Figure 14.1). Volume measures the amount of air for one function (such as inhalation or exhalation). Capacity is any two or more volumes (for example, how much can be inhaled from the end of a maximal exhalation).

| Table 14.1 Lung Volumes and Capacities (Avg Adult Male) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Volume/Capacity | Definition | Volume (liters) | Equations |

| Tidal volume (TV) | Amount of air inhaled during a normal breath | 0.5 | – |

| Expiratory reserve volume (ERV) | Amount of air that can be exhaled after a normal exhalation | 1.2 | – |

| Inspiratory reserve volume (IRV) | Amount of air that can be further inhaled after a normal inhalation | 3.1 | – |

| Residual volume (RV) | Air left in the lungs after a forced exhalation | 1.2 | – |

| Vital capacity (VC) | Maximum amount of air that can be moved in or out of the lungs in a single respiratory cycle | 4.8 | ERV TV IRV |

| Inspiratory capacity (IC) | Volume of air that can be inhaled in addition to a normal exhalation | 3.6 | TV IRV |

| Functional residual capacity (FRC) | Volume of air remaining after a normal exhalation | 2.4 | ERV RV |

| Total lung capacity (TLC) | Total volume of air in the lungs after a maximal inspiration | 6.0 | RV ERV TV IRV |

| Forced expiratory volume (FEV1) | How much air can be forced out of the lungs over a specific time period, usually one second | ~4.1 to 5.5 | – |

The volume in the lung can be divided into four units: tidal volume, expiratory reserve volume, inspiratory reserve volume, and residual volume. Tidal volume (TV) measures the amount of air that is inspired and expired during a normal breath. On average, this volume is around one-half liter, which is a little less than the capacity of a 20-ounce drink bottle. The expiratory reserve volume (ERV) is the additional amount of air that can be exhaled after a normal exhalation. It is the reserve amount that can be exhaled beyond what is normal. Conversely, the inspiratory reserve volume (IRV) is the additional amount of air that can be inhaled after a normal inhalation. The residual volume (RV) is the amount of air that is left after expiratory reserve volume is exhaled. The lungs are never completely empty: There is always some air left in the lungs after a maximal exhalation. If this residual volume did not exist and the lungs emptied completely, the lung tissues would stick together and the energy necessary to reinflate the lung could be too great to overcome. Therefore, there is always some air remaining in the lungs. Residual volume is also important for preventing large fluctuations in respiratory gases (O2 and CO2). The residual volume is the only lung volume that cannot be measured directly because it is impossible to completely empty the lung of air. This volume can only be calculated rather than measured.

Capacities are measurements of two or more volumes. The vital capacity (VC) measures the maximum amount of air that can be inhaled or exhaled during a respiratory cycle. It is the sum of the expiratory reserve volume, tidal volume, and inspiratory reserve volume. The inspiratory capacity (IC) is the amount of air that can be inhaled after the end of a normal expiration. It is, therefore, the sum of the tidal volume and inspiratory reserve volume. The functional residual capacity (FRC) includes the expiratory reserve volume and the residual volume. The FRC measures the amount of additional air that can be exhaled after a normal exhalation. Lastly, the total lung capacity (TLC) is a measurement of the total amount of air that the lung can hold. It is the sum of the residual volume, expiratory reserve volume, tidal volume, and inspiratory reserve volume.

Lung volumes are measured by a technique called spirometry. An important measurement taken during spirometry is the forced expiratory volume (FEV), which measures how much air can be forced out of the lung over a specific period, usually one second (FEV1). In addition, the forced vital capacity (FVC), which is the total amount of air that can be forcibly exhaled, is measured. The ratio of these values (FEV1/FVC ratio) is used to diagnose lung diseases including asthma, emphysema, and fibrosis. If the FEV1/FVC ratio is high, the lungs are not compliant (meaning they are stiff and unable to bend properly), and the patient most likely has lung fibrosis. Patients exhale most of the lung volume very quickly. Conversely, when the FEV1/FVC ratio is low, there is resistance in the lung that is characteristic of asthma. In this instance, it is hard for the patient to get the air out of his or her lungs, and it takes a long time to reach the maximal exhalation volume. In either case, breathing is difficult and complications arise.

Career Connection

Respiratory Therapist

Respiratory therapists or respiratory practitioners evaluate and treat patients with lung and cardiovascular diseases. They work as part of a medical team to develop treatment plans for patients. Respiratory therapists may treat premature babies with underdeveloped lungs, patients with chronic conditions such as asthma, or older patients suffering from lung disease such as emphysema and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). They may operate advanced equipment such as compressed gas delivery systems, ventilators, blood gas analyzers, and resuscitators. Specialized programs to become a respiratory therapist generally lead to a bachelor’s degree with a respiratory therapist specialty. Because of a growing aging population, career opportunities as a respiratory therapist are expected to remain strong.

Gas Pressure and Respiration

The respiratory process can be better understood by examining the properties of gases. Gases move freely, but gas particles are constantly hitting the walls of their vessel, thereby producing gas pressure.

Air is a mixture of gases, primarily nitrogen (N2; 78.6 percent), oxygen (O2; 20.9 percent), water vapor (H2O; 0.5 percent), and carbon dioxide (CO2; 0.04 percent). Each gas component of that mixture exerts a pressure. The pressure for an individual gas in the mixture is the partial pressure of that gas. Approximately 21 percent of atmospheric gas is oxygen. Carbon dioxide, however, is found in relatively small amounts, 0.04 percent. The partial pressure for oxygen is much greater than that of carbon dioxide. The partial pressure of any gas can be calculated by:

[latex]{\text{P = (P}}_{\text{atm}}\text{) }×\text{ (percent content in mixture)}\text{.}[/latex]

Patm, the atmospheric pressure, is the sum of all of the partial pressures of the atmospheric gases added together,

[latex]{\text{P}}_{\text{atm}}{\text{ = P}}_{{\text{N}}_{\text{2}}}{\text{ P}}_{{\text{O}}_{\text{2}}}{\text{ P}}_{{\text{H}}_{\text{2}}\text{O}}{\text{ P}}_{{\text{CO}}_{\text{2}}}\text{= 760 mm Hg}[/latex]

× (percent content in mixture).

The pressure of the atmosphere at sea level is 760 mm Hg. Therefore, the partial pressure of oxygen is:

[latex]{\text{P}}_{{\text{O}}_{\text{2}}}\text{= (760 mm Hg) (0}\text{.21) = 160 mm Hg}[/latex]

and for carbon dioxide:

At high altitudes, Patm decreases but concentration does not change; the partial pressure decrease is due to the reduction in Patm.

When the air mixture reaches the lung, it has been humidified. The pressure of the water vapor in the lung does not change the pressure of the air, but it must be included in the partial pressure equation. For this calculation, the water pressure (47 mm Hg) is subtracted from the atmospheric pressure:

and the partial pressure of oxygen is:

These pressures determine the gas exchange, or the flow of gas, in the system. Oxygen and carbon dioxide will flow according to their pressure gradient from high to low. Therefore, understanding the partial pressure of each gas will aid in understanding how gases move in the respiratory system.

Gas Exchange across the Alveoli

In the body, oxygen is used by cells of the body’s tissues and carbon dioxide is produced as a waste product. The ratio of carbon dioxide production to oxygen consumption is the respiratory quotient (RQ). RQ varies between 0.7 and 1.0. If just glucose were used to fuel the body, the RQ would equal one. One mole of carbon dioxide would be produced for every mole of oxygen consumed. Glucose, however, is not the only fuel for the body. Protein and fat are also used as fuels for the body. Because of this, less carbon dioxide is produced than oxygen is consumed and the RQ is, on average, about 0.7 for fat and about 0.8 for protein.

The RQ is used to calculate the partial pressure of oxygen in the alveolar spaces within the lung, the alveolar [latex]{\text{P}}_{{\text{O}}_{\text{2}}}[/latex]

. Above, the partial pressure of oxygen in the lungs was calculated to be 150 mm Hg. However, lungs never fully deflate with an exhalation; therefore, the inspired air mixes with this residual air and lowers the partial pressure of oxygen within the alveoli. This means that there is a lower concentration of oxygen in the lungs than is found in the air outside the body. Knowing the RQ, the partial pressure of oxygen in the alveoli can be calculated:

[latex]{\text{alveolar P}}_{{\text{O}}_{\text{2}}}{\text{= inspired P}}_{{\text{O}}_{\text{2}}}\text{− (}\frac{{\text{alveolar P}}_{{\text{O}}_{\text{2}}}}{\text{RQ}}\text{)}[/latex]

With an RQ of 0.8 and a [latex]{\text{P}}_{{\text{CO}}_{\text{2}}}[/latex]

in the alveoli of 40 mm Hg, the alveolar [latex]{\text{P}}_{{\text{O}}_{\text{2}}}[/latex]

is equal to:

[latex]{\text{alveolar P}}_{{\text{O}}_{\text{2}}}\text{ = 150 mm Hg − (}\frac{\text{40 mm Hg}}{\text{0}\text{.8}}\text{) = 100 mm Hg}\text{.}[/latex]

Notice that this pressure is less than the external air. Therefore, the oxygen will flow from the inspired air in the lung ([latex]{\text{P}}_{{\text{O}}_{\text{2}}}[/latex] = 150 mm Hg) into the bloodstream ([latex]{\text{P}}_{{\text{O}}_{\text{2}}}[/latex] = 100 mm Hg)

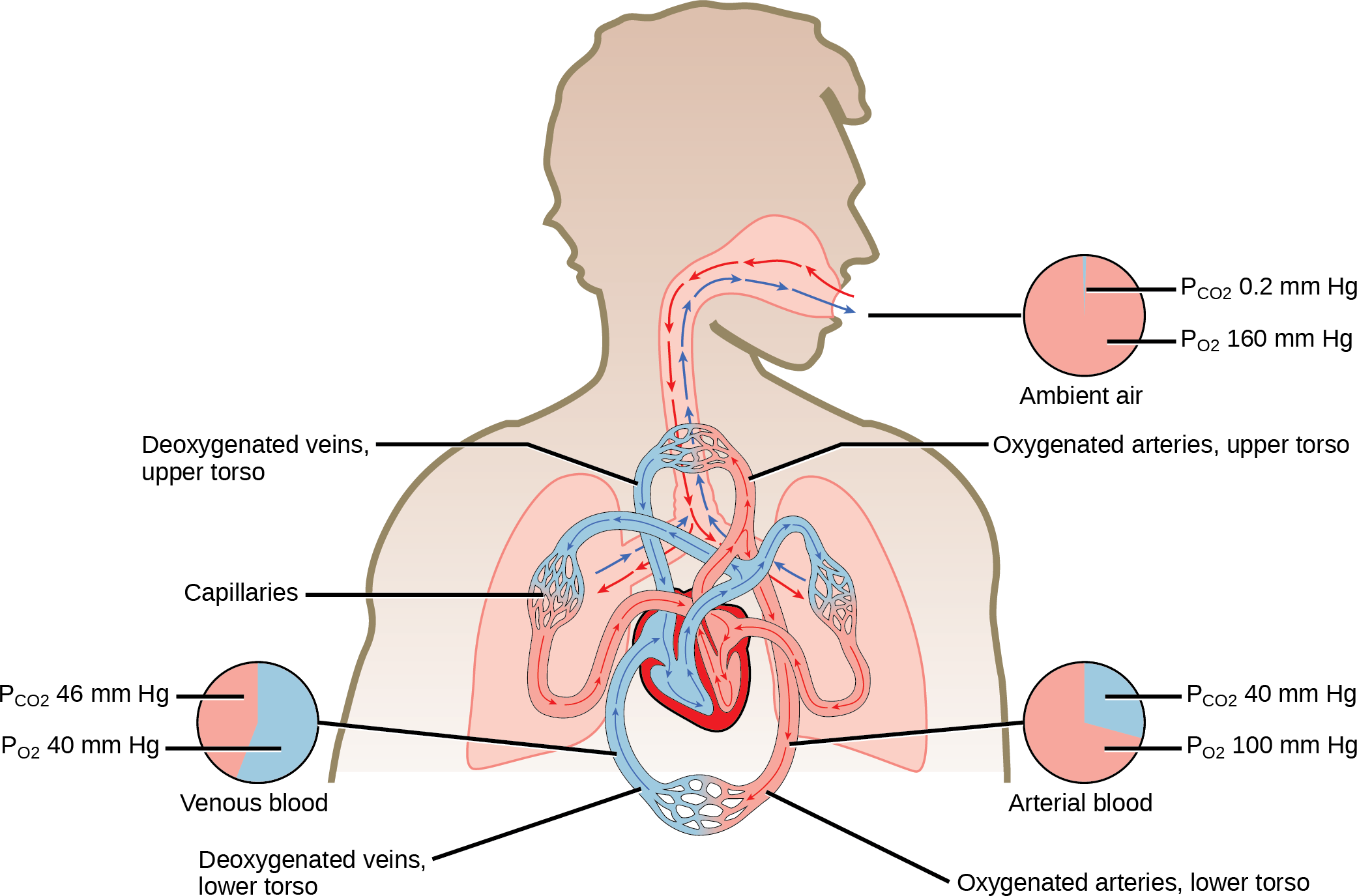

In the lungs, oxygen diffuses out of the alveoli and into the capillaries surrounding the alveoli. Oxygen (about 98 percent) binds reversibly to the respiratory pigment hemoglobin found in red blood cells (RBCs). RBCs carry oxygen to the tissues where oxygen dissociates from the hemoglobin and diffuses into the cells of the tissues. More specifically, alveolar [latex]{\text{P}}_{{\text{O}}_{\text{2}}}[/latex]

is higher in the alveoli ([latex]{\text{P}}_{{\text{ALVO}}_{\text{2}}}[/latex] = 100 mm Hg)

than blood [latex]{\text{P}}_{{\text{O}}_{\text{2}}}[/latex] (40 mm Hg) in the capillaries. Because this pressure gradient exists, oxygen diffuses down its pressure gradient, moving out of the alveoli and entering the blood of the capillaries where O2 binds to hemoglobin. At the same time, alveolar [latex]{\text{P}}_{{\text{CO}}_{\text{2}}}[/latex]

is lower [latex]{\text{P}}_{{\text{ALVO}}_{\text{2}}}[/latex] = 40 mm Hg

than blood [latex]{\text{P}}_{{\text{CO}}_{\text{2}}}[/latex] = (45 mm Hg). CO2 diffuses down its pressure gradient, moving out of the capillaries and entering the alveoli.

Oxygen and carbon dioxide move independently of each other; they diffuse down their own pressure gradients. As blood leaves the lungs through the pulmonary veins, the venous [latex]{\text{P}}_{{\text{O}}_{\text{2}}}[/latex]= 100 mm Hg, whereas the venous [latex]{\text{P}}_{{\text{CO}}_{\text{2}}}[/latex] = 40 mm Hg. As blood enters the systemic capillaries, the blood will lose oxygen and gain carbon dioxide because of the pressure difference of the tissues and blood. In systemic capillaries, [latex]{\text{P}}_{{\text{O}}_{\text{2}}}[/latex]= 100 mm Hg, but in the tissue cells, [latex]{\text{P}}_{{\text{O}}_{\text{2}}}[/latex]= 40 mm Hg. This pressure gradient drives the diffusion of oxygen out of the capillaries and into the tissue cells. At the same time, blood [latex]{\text{P}}_{{\text{CO}}_{\text{2}}}[/latex]= 40 mm Hg and systemic tissue [latex]{\text{P}}_{{\text{CO}}_{\text{2}}}[/latex]= 45 mm Hg. The pressure gradient drives CO2 out of tissue cells and into the capillaries. The blood returning to the lungs through the pulmonary arteries has a venous [latex]{\text{P}}_{{\text{O}}_{\text{2}}}[/latex]= 40 mm Hg and a [latex]{\text{P}}_{{\text{CO}}_{\text{2}}}[/latex]= 45 mm Hg. The blood enters the lung capillaries where the process of exchanging gases between the capillaries and alveoli begins again ((Figure 14.13)).

Visual Connection

In short, the change in partial pressure from the alveoli to the capillaries drives the oxygen into the tissues and the carbon dioxide into the blood from the tissues. The blood is then transported to the lungs where differences in pressure in the alveoli result in the movement of carbon dioxide out of the blood into the lungs, and oxygen into the blood.

Link to Learning

Watch this video to learn how to carry out spirometry.

Section Summary

The lungs can hold a large volume of air, but they are not usually filled to maximal capacity. Lung volume measurements include tidal volume, expiratory reserve volume, inspiratory reserve volume, and residual volume. The sum of these equals the total lung capacity. Gas movement into or out of the lungs is dependent on the pressure of the gas. Air is a mixture of gases; therefore, the partial pressure of each gas can be calculated to determine how the gas will flow in the lung. The difference between the partial pressure of the gas in the air drives oxygen into the tissues and carbon dioxide out of the body.

Review Questions

Glossary

- alveolar [latex]{\text{P}}_{{\text{O}}_{\text{2}}}[/latex]

- partial pressure of oxygen in the alveoli (usually around 100 mmHg)

- expiratory reserve volume (ERV)

- amount of additional air that can be exhaled after a normal exhalation

- FEV1/FVC ratio

- ratio of how much air can be forced out of the lung in one second to the total amount that is forced out of the lung; a measurement of lung function that can be used to detect disease states

- forced expiratory volume (FEV)

- (also, forced vital capacity) measure of how much air can be forced out of the lung from maximal inspiration over a specific amount of time

- functional residual capacity (FRC)

- expiratory reserve volume plus residual volume

- inspiratory capacity (IC)

- tidal volume plus inspiratory reserve volume

- inspiratory reserve volume (IRV)

- amount of additional air that can be inspired after a normal inhalation

- lung capacity

- measurement of two or more lung volumes (how much air can be inhaled from the end of an expiration to maximal capacity)

- lung volume

- measurement of air for one lung function (normal inhalation or exhalation)

- partial pressure

- amount of pressure exerted by one gas within a mixture of gases

- residual volume (RV)

- amount of air remaining in the lung after a maximal expiration

- respiratory quotient (RQ)

- ratio of carbon dioxide production to each oxygen molecule consumed

- spirometry

- method to measure lung volumes and to diagnose lung diseases

- tidal volume (TV)

- amount of air that is inspired and expired during normal breathing

- total lung capacity (TLC)

- sum of the residual volume, expiratory reserve volume, tidal volume, and inspiratory reserve volume

- venous [latex]{\text{P}}_{{\text{CO}}_{\text{2}}}[/latex]

- partial pressure of carbon dioxide in the veins (40 mm Hg in the pulmonary veins)

- venous [latex]{\text{P}}_{{\text{O}}_{\text{2}}}[/latex]

- partial pressure of oxygen in the veins (100 mm Hg in the pulmonary veins)

- vital capacity (VC)

- sum of the expiratory reserve volume, tidal volume, and inspiratory reserve volume

Chapter 39 in OpenStax Concepts of Biology 2e