1. Building Connections that Support Emergent Literacy

“Children are born with wings. Teachers help them to fly.”

-Shelby Stollery

1.2 Empowering Approaches to Literacy Development

1.3 What is Emergent Literacy?

Opening Vignette: Climbing Together

1.1 Introduction

Young children such as Marvin, Maria, and John have diverse abilities and experiences with language. They are each at different places in terms of their physical stage of development, previous experiences, and expectations of what they think they can do. They use language in different ways. At times, they speak, beckon, or make other gestures. They laugh and smile to signal pleasure and cry out in pain, anger or frustration. They use language for enjoyment and for resolution of problems. They are listening and speaking, communicating non-verbally, and developing concepts that support their comprehension and vocabulary. They can share meaning by expressing themselves and understanding language. Young children are beginning to demonstrate that they can communicate a message through writing.

This textbook, Early Childhood Literacy: Engaging and Empowering Emergent Readers and Writers Birth-Age 5, outlines the connection between different areas of language and literacy and describes strategies for supporting development and promoting instruction. Early literacy includes reading, writing, and language development. Writing includes any early writing attempts and pre-writing behaviors just as reading includes any early reading attempts and recognition of symbols and sounds. Language also includes listening and speaking (oral language) and the use of gestures and signs to communicate. The term oral language is commonly used to describe early language development separately from reading and writing. This text assumes oral language is a component of language and embraces the broader term to underscore the communication practices outside of listening and speaking. For example, some children use sign language or a picture board. For these reasons, the textbook will focus on language development in its totality, including oral language. This textbook is focused on birth to age 5 because early literacy development is crucial for future learning and development. This introductory chapter will explore the following questions:

- Why do we use a strengths-based approach when we consider what literacy development is?

- What is emergent literacy?

- What is the nested model of literacy?

- What definitions and terms of common literacy are important to know?

1.2 Empowering Approaches to Literacy Development

Each child has unique strengths and uses strategies they learn are successful to foster literacy development. It is crucial to start with an approach that emphasizes what children can do instead of what they cannot yet achieve. An approach that begins with examining deficits often over-emphasizes what children lack instead of their capacities. Children’s literacy experiences are housed within relationships and opportunities. An integrated approach acknowledges that reading, writing, and language development are connected and contextualized by children’s experiences. Language development, and later reading and writing, are vehicles for comprehension, even as our increasing comprehension helps us to form each of these three areas. The components of literacy develop incrementally and they all foster the development of the other components. Literacy development requires a holistic approach, focusing on understanding the whole child across contexts and time with a strengths-based focus.

This textbook acknowledges the importance of collaboration in a strengths-based focus as it fosters cultural responsiveness and an integrated approach to learning. By starting with the expectation that there are multiple perspectives to be heard and valued, educators are better equipped to embrace and respond to the needs of children and families. Strong communication among all of the adults that make up the context of the child’s life promotes the opportunities for children and families to have input and influence in the environment. This, in turn, fosters positive outcomes for children’s literacy development.

1.3 What is Emergent Literacy?

Emergent literacy is based on the notion that children acquire knowledge about reading, writing, and language before they have begun any formal education (Clay, 1966, 2001; Sulzby & Teale, 1982; Whitehurst & Lonigan, 1998, 2001). This conceptualization of literacy as a developmental process that begins at birth counters previous early literacy theories that believed readiness for learning to read began with formal schooling (Whitehurst & Lonigan, 1998). Many researchers have contributed to our understanding of literacy development in the earliest years. According to Marie Clay (1966), literacy development begins early in life and is ongoing. Teale (1987) explained that children not only have particular experiences before they start school, but they also have developed interests. Emergent literacy is the result of children’s involvement in reading activities facilitated by literate adults (Teale, 1982). Sulzby and Teale (1991) define emergent literacy as the reading and writing behaviors that precede and develop into conventional literacy. These early literacy behaviors indicate a child’s stage of reading and are particularly revealing in determining the approaches a child will use as they engage in the task of reading. Similarly, Whitehurst and Lonigan (1998) define emergent literacy as a “developmental continuum between prereading and reading involving skills, knowledge and attitudes that are the developmental precursors to reading and writing” (1998, p. 484). This underscores that we expect children to acquire skills over time. Additionally, Whitehurst and Lonigan (2001) have clarified that emergent reading develops in an interactive process of skills and context, rather than individual components developing in a linear fashion.

All of these definitions of emergent reading help us understand that long before children are reading books word for word, they are acquiring important literacy knowledge and skills. For example, many young children can point out commonly visited store logos with no prompting. Any adult who has ever heard a toddler in the backseat point to the fast food restaurant and scream, “fry-fries!” has witnessed emergent reading. It is not simply about the quantity of skills a child develops before appearing to be a fluent reader. Rather a child’s literacy develops over a long period of time, with early skills supporting the growth or emergence of new skills.

Emergent literacy and early literacy are often used interchangeably, but this textbook will use the term emergent literacy, encompassing everything a child knows about reading and writing before they become proficient. Emergent literacy can be thought of as the totality of the language capacities, knowledge, and skills a child possesses even before developing the ability to turn that knowledge into reading in ways that are measured as conventional skills. Children are developing reading, writing, and language concurrently during their earliest years. All of the key concepts in emergent literacy occur on a developmental continuum and involve stages of learning.

1.4 Emergent Literacy Areas

The National Literacy Panel (2010) defined literacy by identifying and defining skills, both in the earliest stages as precursor skills and later stages as conventional skills. We can examine behaviors evident in emergent literacy, including three broad areas of literacy skills: language development, reading, and writing, which can be further broken down into specific indicators.

Vignette: What’s on the Menu?

This interaction displays many of the characteristics of emergent literacy behaviors. Marvin and Maria are engaging in conversation and connecting stories to their experiences. They pretend to read and pretend to write as well as use oral language to communicate their ideas. These types of social exchanges provide an opportunity to practice the behaviors that will help prepare children to proficiently read and write.

1.4a Language Development

Language development tends to be conceptualized as receptive language, expressive language, and the interaction between communicators. Receptive language involves receiving, interpreting, comprehending and decoding. Expressive language is the production or encoding of information. Speaking, listening, and non-verbal communication allow children the opportunity to use words and gestures to express ideas and feelings. Language requires an understanding of vocabulary (choice of words), context (how and when words are used), and language conventions (rules for using words in meaningful ways). For example, a child may use different vocabulary or tone of voice with a sibling than they might with a stranger or a grandparent. Language may also be non-verbal through the use of sign language, gestures, and non-verbal cues (facial expressions and body language). Language development is pivotal to the growth of a child’s reading and writing development. In the vignette above, we see that Marvin and Maria are using language to express and receive information as they debate whether or not ketchup is on the menu.

Pause and Consider: Attunement

1.4b Reading

Reading is a complex process. It requires readers to continually decode and comprehend a written message. Decoding requires the reader to connect letter symbols and sounds, while comprehension involves understanding the meaning of written text. The report of the National Reading Panel (NICHD, 2000) identified five key components of reading. These five areas are (a) phonemic awareness, (b) phonics, (c) fluency, (d) vocabulary, and (e) comprehension. While these five components are important, the original report did not address emergent reading practices in birth to five-year-old children. A more expansive definition of reading would include a variety of observable behaviors and skills exhibited before a child is able to connect sound-symbol relationships or become fluent readers. Children are engaging in many prereading tasks and preparing for conventional reading in their earliest years. The report of the National Early Literacy Panel indicated that preconventional reading skills include print concepts, alphabet knowledge, print knowledge, phonological awareness, vocabulary, and oral language (National Institute for Literacy, 2008). When Marvin picks up the menu to “read it,” he is engaging in emergent reading behaviors.

1.4c Writing

Writing progresses in stages and in a bidirectional fashion with reading. While reading is a manner of receiving communication, writing offers a way to visually represent and produce communication. Sulzby and Teale (1991) indicate that scribbling as intentional writing can be observed in children as young as 18 months. They go on to say that scribbling represents the beginnings of writing for most children. Eventually children will move from scribbling to increasingly sophisticated markings in order to communicate meaning to themselves or others. In the example with Marvin and Maria above, Marvin acts out this expectation of shared meaning when he hands the teddy bear a bill. These emergent writing behaviors help prepare children for conventional writing later.

1.5 Nested Literacy

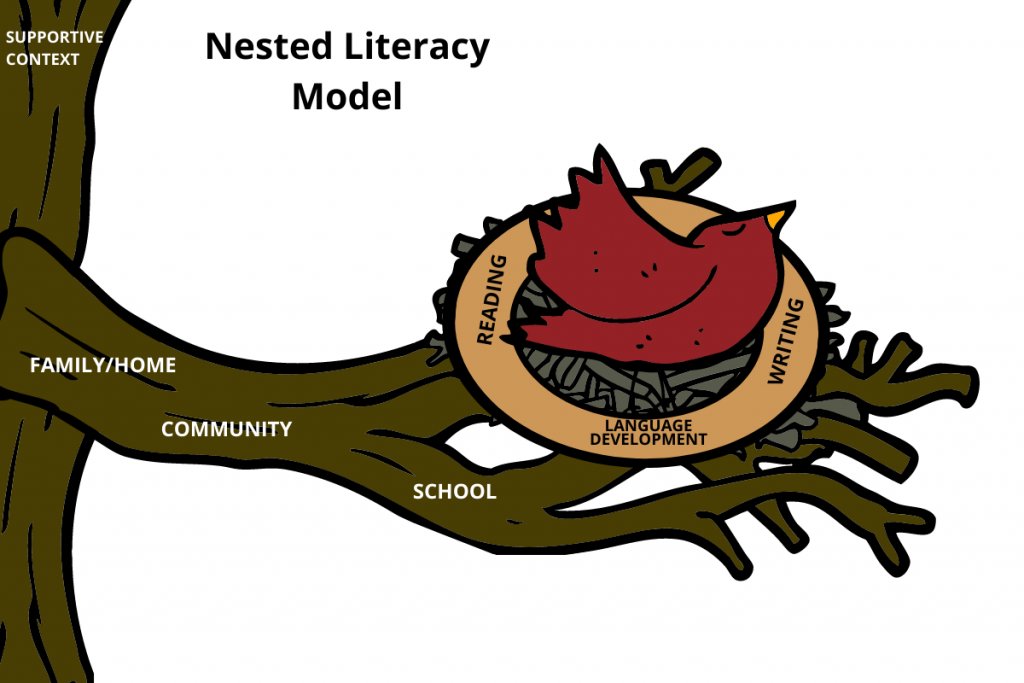

Literacy includes language, reading, and writing, which are interrelated concepts that reflect and support a child’s overall thinking. Within these concepts are discrete areas that support the development of the broader concepts listed above. Literacy development is contextual, occurring within the supportive environments of the home and school, where family members and teachers support the development of the child through interactions, location specific opportunities, and relationships. We have developed a model to illustrate how this learning occurs, and we have chosen to organize the book around these central concepts (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Nested Literacy Model

1.5a The Nest

The overarching literacy concepts frame the nest and surround the bird. The three concepts, language development, writing, and reading are interconnected and collectively support the child’s literacy development. A child’s capacity for developing their reading, writing, and language skills is continuous. In other words, as the child continues to engage in meaningful interactions with others, reading, and writing, they will expand and enhance their proficiencies within each literacy concept. While the overarching literacy concepts are continuous, children bolster their literacy knowledge when they acquire discrete literacy skills as well. Discrete skills (e.g., directionality of text, phonemic awareness, alphabet and word awareness,) support children’s literacy progression. In contrast to continuous literacy concept development, once a child acquires a discrete skill, that knowledge is then used by the child to engage in subsequent literacy experiences.

1.5b The Bird

In the nested literacy model, the child is in the center, represented in our model by the bird. Children bring with them into their learning environments prior knowledge, language experiences, and print knowledge. Their experiences bring opportunities for the child to strengthen the literacy concepts (i.e., language development, reading, and writing) and acquire new knowledge. As the child interacts with their environment and is provided with literacy-rich opportunities, the child’s emergent literacy abilities develop and grow. The child uses these abilities to engage family members, classmates, and others, establishing a continuous and iterative cycle of literacy learning.

1.5c The Branch

The home/family, community, and school environments are the wider contexts in which the child is quite literally nested. As a child interacts with the environment, they develop expressive and receptive language, reading, and writing skills. The tree branch supports the nest and the child as they continue to grow and construct meaning while engaging in social interactions. The tree branch literally provides a scaffold for the child and highlights the importance of a supportive environment. Rich literacy interactions and cognitive growth are enhanced when the environmental factors and contexts (e.g., school, community, family, health, economic) provide a positive and healthy space for children to explore, interact, and engage. All of these elements will be explored in detail in subsequent chapters and continue to demonstrate the interactions among the child, the emergent literacy components, and the broader environmental factors that enhance children’s emerging literacies.

1.6 Textbook Organization

We hope that this text will help you understand the wider picture of how emergent literacy develops and provide concrete strategies for incorporating literacy rich opportunities for young children into your classroom. Part I (Chapters 1-3) illustrates development in the early years and the theories that inform best practices for literacy. Part II (Chapters 4-6) addresses contexts for learning, environmental supports, and assessment. Part III (Chapters 7-10) addresses language development, reading, and writing, and presents the progression of literacy development.

To enhance readers’ engagement with the book, we include a number of features to promote educators’ visualizations of a variety of literacy concepts and practices. Each chapter uses vignettes to illustrate children’s literacy experiences. The vignettes are drawn from our collective experiences working with young children and families over the years. Throughout the chapters, we also integrate Pause and Consider boxes to provide places for readers to stop and reflect on essential concepts as they are presented. At the end of each chapter, we provide a Key Take-Aways box followed by a Resource box with links to complementary materials for educators to consider. Embedded within each chapter, icons representing the bird, nest, or branch are also included to support the reader’s attention back to the Nested Literacy Model. Finally, to provide readers with windows into early childhood classrooms, the book also includes photographs of young children immersed in literacy experiences. Readers will notice that many photos include children and educators wearing masks. Rather than remove these images, we intentionally retain the photos to serve as historical reminders of the essential role early educators played in supporting our youngest children and their families throughout the global pandemic. We value the work early educators do to nurture every child, and we hope this text extends the literature available to early educators in meaningful and personally relevant ways. We hope you enjoy the journey.

Pause and Consider

Key Take-Aways

Additional Resources

National Association for Education of Young Children: https://www.naeyc.org/

Virginia’s Early Learning & Development Standards (ELDS): Birth-Five Learning Guidelines. https://www.doe.virginia.gov/early-childhood/curriculum/va-elds-birth-5.pdf

Zero to Three: https://www.zerotothree.org/

References

Bloom, L., & Lahey, M. (1978). Language development and language disorders. Wiley.

Clay, M. M. (2001). Change over time in children’s literacy development. Heinemann.

Clay, M. M. (1966). Emergent reading behaviour. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. University of Auckland, New Zealand.

Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, NIH, DHHS. (2010). Developing early literacy: Report of the National Early Literacy Panel (NA). U.S. Government Printing Office.

National Reading Panel (U.S.), & National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (U.S.). (2000). Report of the National Reading Panel: Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction: Reports of the subgroups. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Saracho, O. N. (2002). Young children’s literacy development. In O. N. Saracho & B. Spodek (Eds.), Contemporary perspectives on early childhood curriculum (Vol. 1, pp. 111–130). Information Age Publishing.

Sulzby, E., & Teale, W. (1985). Writing development in early childhood. Education Horizons, 64, 8–12.

Sulzby, E., & Teale, W. H. (1991). Emergent literacy. In R. Barr, M. L. Kamil, P. Mosenthal, & P. D. Pearson (Eds.), Handbook of reading research (Vol. 2, pp. 727–757). Longman.

Teale, W. H. (1982). Toward a theory of how children learn to read and write naturally. Language Arts, 59, 555–570.

Whitehurst, G. J., & Lonigan, C. J. (1998). Child development and emergent literacy. Child Development, 69, 848–872.

Whitehurst, G. J., & Lonigan, C. J. (2001). Emergent literacy: Development of prereaders to readers. In S. B. Neuman & D. K. Dickinson (Eds.), Handbook of early literacy research (Vol.1, pp.11–29). Guilford.

Image Credits

Figure 1.1: Kalyca Schultz and Christine Schull. “Nested Literacy Model.” CC-BY 2.0.

Additional Images

Image, Section 1.2: Longwood University. [Children Working] CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.