2. Recognizing the Power of the Early Years

“There’s been a revolution in our scientific understanding of babies and young children. We used to think that babies and young children were irrational, egocentric, and amoral. Their thinking and experiences were concrete, immediate, and limited. In fact, psychologists and neuroscientists have discovered that babies not only learn more, but imagine more, care more, and experience more than we would ever have thought possible. In some ways, young children are actually smarter, more imaginative, more caring, and even more conscious than adults are.”

-Gopnik, 2009, p. 5

2.2 What We Know About the Brain

2.3 The Role of Adults in Children’s Brain Development

Opening Vignette: Harrison’s Glove

2.1 Introduction

We know a great deal about what happens during the first five years of life and how critical development during this window is to future success (Center on the Developing Child, 2007; National Research Council & Institute of Medicine, 2000). This knowledge also has key implications for literacy development and early childhood educators’ practices. For these reasons, we are opening this textbook with a broader discussion about some of the key scientific discoveries about the brain. We hope this information and the subsequent resources help frame the discussion about literacy learning and give early childhood educators the tools to advocate for young children. This chapter will answer the following questions:

What do we know about brain development and how it impacts children’s vision, hearing, language, cognition, motor skills, and social/emotional competence?

What do we know about brain development and how it impacts children’s vision, hearing, language, cognition, motor skills, and social/emotional competence?

How do the adults in children’s lives play key roles in fostering brain architecture?

How do the adults in children’s lives play key roles in fostering brain architecture?

Why are early childhood educators, in specific, such a dynamic factor in overall brain development and laying the foundation for literacy learning?

Why are early childhood educators, in specific, such a dynamic factor in overall brain development and laying the foundation for literacy learning?

2.2 What We Know About the Brain

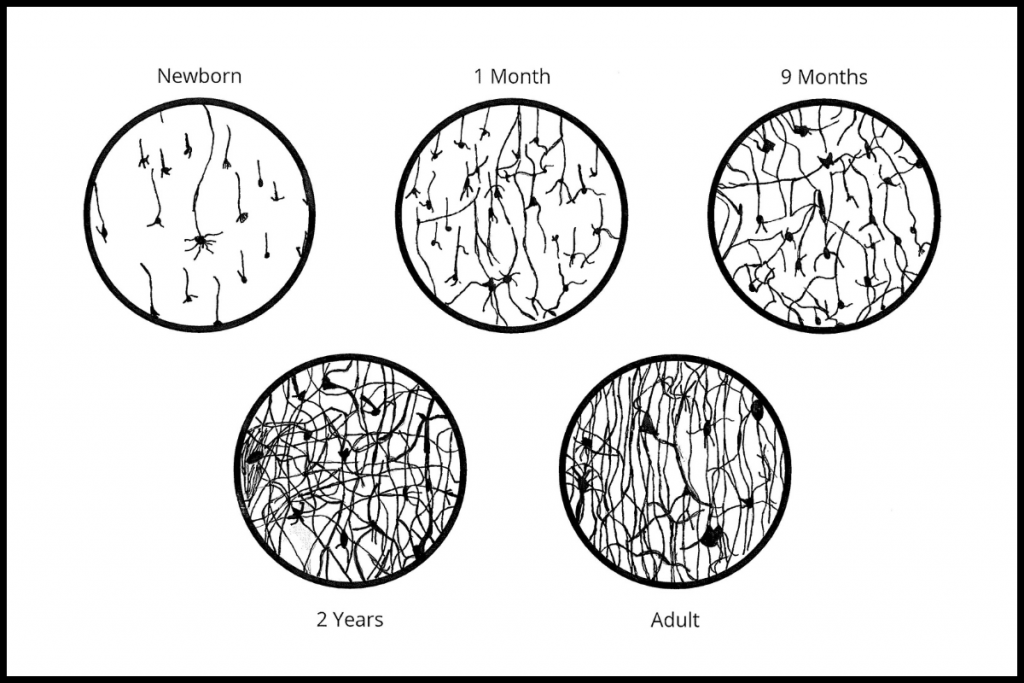

There is little argument that brain science has elevated the discussion about the importance of development from birth to age five (National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2007; IOM & NRC, 2015). These years are fundamental in brain growth in a way that is unique from other time periods. What we do in these years matters–the risks are more pronounced and the opportunities for enrichment more impactful. Babies’ brains are roughly one quarter the size of an adult brain; however, at birth a baby has 100 billion neurons (UNICEF ECARO & ISSA, 2016). Neurons are cells designed to carry messages from one part of the brain to another part. All of these billions of neurons are present in the brain at birth, but most are not connected. The brain continues to develop throughout the lifespan; however, more than a million neural connections, or synapses, are made each second in the first few years of life (Center on the Developing Child, 2007). Graham & Forstadt (2011) explain,

Each individual neuron may be connected to as many as 15,000 other neurons, forming a network of neural pathways that is immensely complex. This elaborate network is sometimes referred to as the brain’s ‘wiring’ or ‘circuitry.’ As the neurons mature, more and more synapses are made. At birth, the number of synapses per neuron is 2,500, but by age two or three, it’s about 15,000 synapses per neuron. This is like going from 100 to 600 friends on Facebook, and each of those friends in turn, is connected to 600 more people! The neural network expands exponentially.

Because of the extensive neural connections during early childhood (see Figure 2.1 below), this age range is considered one of the “sensitive periods” when the brain is naturally geared toward learning. Brain researchers tell us that the brain is more malleable or has more “plasticity” in early childhood. This means that during the first few years of childhood the brain is more susceptible, and this susceptibility can have two inverse impacts. Ideally, early experiences prepare young children for the future by establishing capabilities when development is most responsive to stimulation. However, it is also possible that in a less than ideal setting, the young child is more vulnerable to the absence of these essential experiences resulting in the risk of future brain dysfunction (National Research Council & Institute of Medicine, 2000).

Essentially, the simple circuits that are built during early childhood enable complex circuits to more easily build onto the initial pathways (Center on the Developing Child, 2007). A literacy example of how these pathways work is how verbally labeling an object depends upon the earlier ability to differentiate and create the sounds required for that word in the child’s language. Additionally, the ability to verbally label an object then leads to the skill of grouping words into phrases and using this language to read or write words and phrases. If these circuits are used over and over again, they become more efficient, but those that are not used fade away or are “pruned.”

Figure 2.1 Neural Connections in Early Childhood

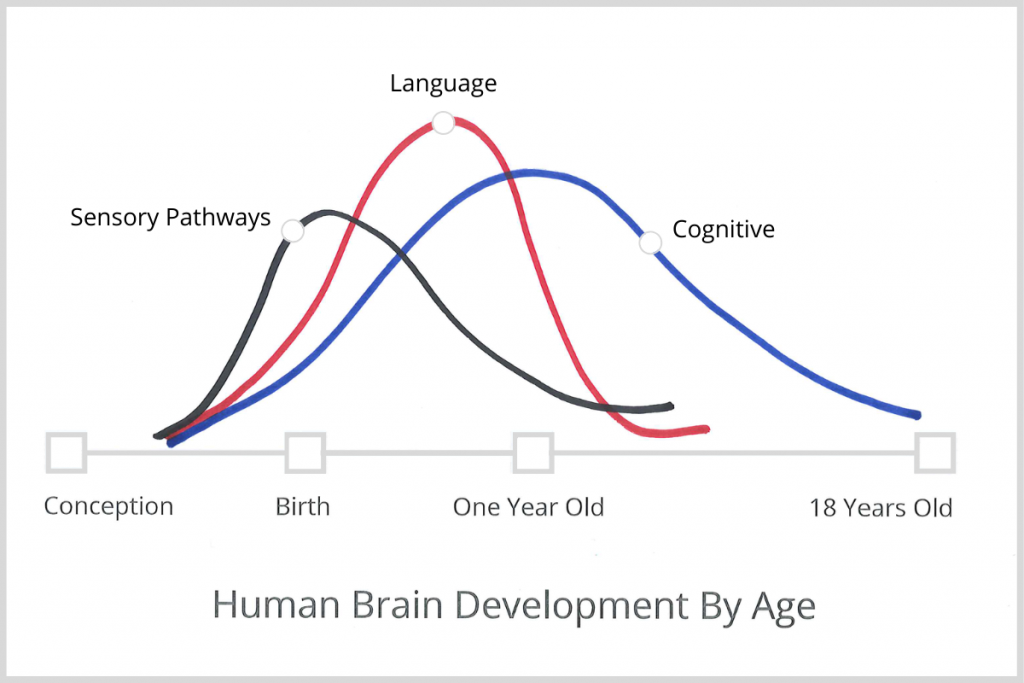

There are a number of ways that brain architecture is impacted during the birth-to-five window. The development and strengthening of circuits forms the foundation of, among other things, emotional regulation, motor control, cognition, language development, and more. Figure 2.2 shows three different brain functions that develop sequentially. You will notice that all three functions expand significantly in the first five years and are directly connected to children’s literacy development. The first, sensory pathways, are important for initial communication and support the development of language. We will spend an entire chapter in this textbook (see Chapter 7) on language, the second function. Language plays a critical role in building foundational literacy competencies and develops in distinct but overlapping stages; however, the quality of language that children hear impacts development. The last function displayed in Figure 2.2 is cognition. This includes memory, sustained attention, mental flexibility, the ability to make a plan, among other skills. Researchers also know that gross motor skills, such as crawling, walking, and balance, are predictive of cognitive function and impacted by brain development. It is clear from the brain research that these functions are critical for overall development and impact children’s literacy foundation.

Figure 2.2 Human Brain Development by Age

Another function of the brain not shown in the figure is social competence. Research has shown that children’s ability to identify and express emotions, cope with strong feelings, engage in self-regulation, and develop empathy in early childhood are all key markers to forming successful relationships later in life and becoming a productive member of society (Levitt & Eagleson, 2018; National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2004). A number of studies have shown that children who have acquired these skills by kindergarten have an increased rate of graduating from high school, attending and completing college, and finding and maintaining employment in adulthood (Jones, Greenberg, & Crowley, 2015).

This research also showed an inverse relationship between low levels of social skills and increased predictability of substance abuse behavior, involvement in the justice system (e.g. being arrested), and needing public assistance. It is clear that supporting children’s emotional foundation by the end of preschool is vitally important. An emotional foundation is important for social competence and also impacts children’s success in school.

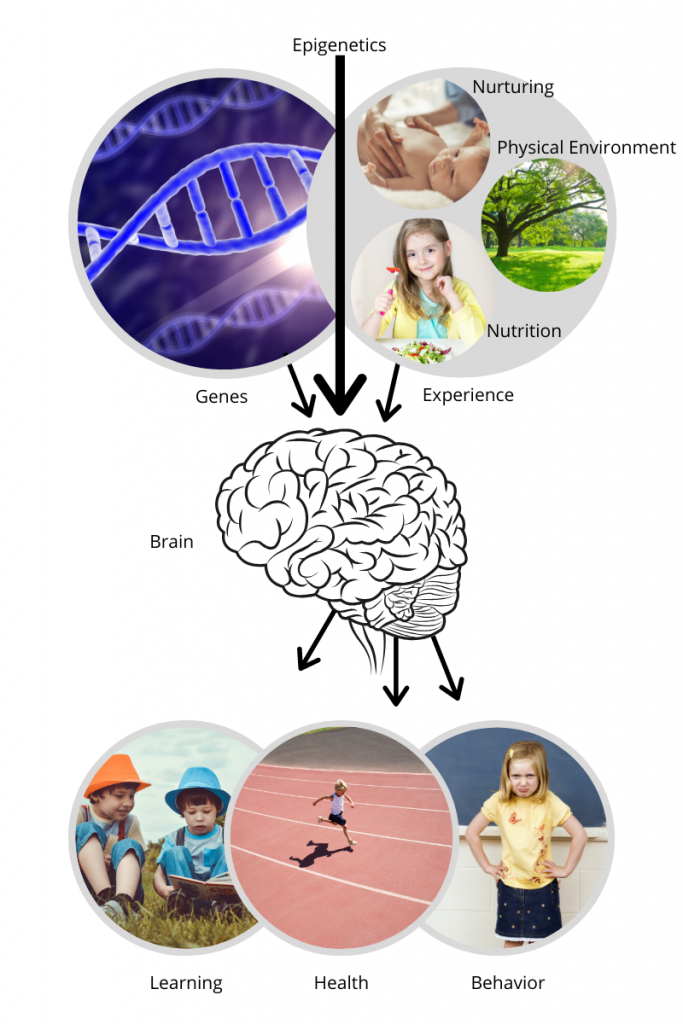

Brain development is impacted by many factors including genes, relationships, environments, and experiences. The quality of the environment and experiences impact how genes are expressed and how the brain architecture is structured. These elements are also often tied to the type of relationships that children establish with adults and collectively build the foundation of the brain’s structure. The figure below (McCain, M., Mustard, J.F. & McCuaig, K., 2011, p. 39) shows how these factors interact with brain development.

Figure 2.3 Factors Influencing Brain Development

The brain changes in many amazing ways during the early childhood window, but precisely for this reason, there are also factors that can have a negative impact on development. It is important for early childhood educators to understand the impact that trauma and adversity can have on the developing brain. The vast promise of early brain development is a tremendous opportunity to impact children’s entire school experience as well as future life trajectory. But with this opportunity also comes significant challenges if children are experiencing trauma. Stress creates a physiological response in the body, which is healthy in small doses, but toxic stress from traumatic events negatively impacts brain development. Continually elevated cortisol levels can be toxic for the developing brain and have serious implications for learning and behavior (Center on the Developing Child, 2007). As important as these implications are, it is also critical to know that this is not necessarily the end of the story. The impact of toxic stress can be mitigated by developing resilience through relationships.

2.3 The Role of Adults in Children’s Brain Development

2.3 The Role of Adults in Children’s Brain Development

The rapid growth of the brain during birth to age five puts an increased emphasis on the importance of the adults in the child’s life during this timeframe. As we discussed in the previous section, brain development is impacted by various factors and adults influence the vast majority of these factors. For instance, adults determine what types and the variety of environments and experiences children are exposed to, including in the home, community, and school. Adults also play a vital role in the quality of interactions and relationships that are developed with the child. These interactions and relationships play a key role in children’s brain development.

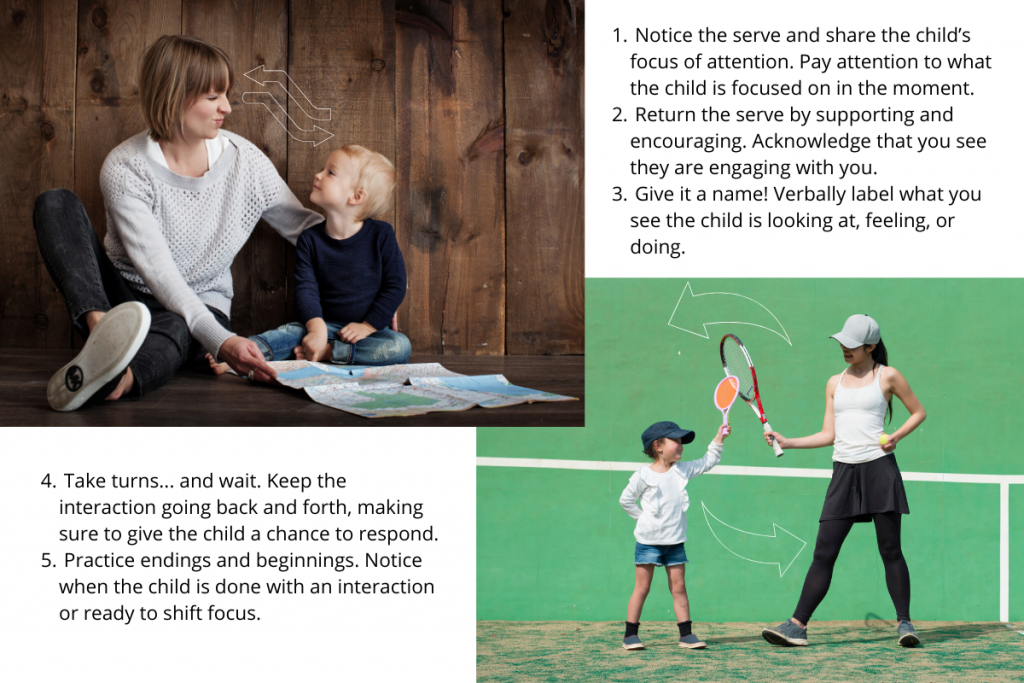

2.3a Promoting Interactions with Children

There has been a great deal of research done on the importance of interactions between adults and children. Brain researchers refer to this interaction as the “serve and return” response (Center on the Developing Child, 2007). If you watch a young child carefully, they are regularly reaching out for interaction with adults. Think of this as the “serve” in a tennis match. The adult then has the opportunity to “return” the ball by responding to the child in some way. These serve and return interactions are vital for brain development and are one key way that adults support young children’s development. Filming Interactions to Nurture Development (FIND) delineates five steps to practice serve and return interactions with young children (see Figure 2.4 below).

Figure 2.4 Serve and Return

Additional Resources

Pause and Consider: Serve and Return with Harrison’s Glove

2.3b Nurturing Relationships with Children

While relationships are important to children’s development for many reasons, the impact on brain development in many ways hinges on the quality of the relationship. Relationships play a key role in the serve and return process (or interactions) because brain researchers have found that this format works best when a caring relationship has been established with the child (National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2007). Researchers have found that “mutually rewarding relationships” are key to further brain development.

The presence of caring relationships with adults that result in quality interactions lays the groundwork for continued brain development. These types of relationships also create secure attachments, which have been shown to positively impact children’s emotional regulation and cognitive functioning (Center on the Developing Child, 2007). As with the impact of trauma, it is important to note what the absence of secure relationships does to children’s brain development. National Scientific Council on the Developing Child (2012) notes,

When decreased responsiveness persists, the lost opportunities associated with diminished interaction can be compounded by the adverse impacts of excessive stress activation, the physiological effects of which can have lifelong consequences. This multidimensional assault on the developing brain underscores why significant deprivation is so harmful in the earliest years of life and why effective interventions are likely to pay significant dividends in better long-term outcomes in learning, health, and parenting of the next generation.

It is clear that children without secure adult attachments will have difficulty engaging with other adults and children in the classroom, directly impacting their further brain development. Early maladaptive relationships can create a cyclical problem; few secure relationships in early childhood can create difficulty developing secure attachments in the future.

2.4 Importance of Early Childhood Educators in the Equation (BRANCH)

2.4 Importance of Early Childhood Educators in the Equation (BRANCH)

As adults who play an important role in the lives of children, early childhood educators play a critical role in brain development. However, the level of importance of this workforce has in many ways historically been undervalued. For instance, early childhood educators are typically the lowest paid in the field, compared to their peers in the K-12 system. On average, early childhood educators make merely $10-$13 per hour (Loewneberg, 2018). Also, standards and competencies have varied widely in this workforce, due in large part to an uninformed perspective that working with young children requires less skill. Knowing what we do now about the critical nature of brain development, it is clear that this workforce is at least as important if not more important than other educators and that there are different, but equally important competencies required (IOM & NRC, 2015).

Looking at the importance of early childhood educators from a numerical perspective, the number of children throughout the United States in care and education settings from birth through age five is over 60% of the population (Childstats.gov, 2018). With well over half of children in the U.S. being cared for and educated by someone in addition to the support they receive in the home, it becomes clear that the work of these educators has a significant impact on children’s development. Having a highly skilled workforce is vital to ensure that we capitalize on children’s learning potential.

As discussed in the last section, secure attachments are vitally important. Early childhood educators have the capacity to build these interactions and relationships as well as develop the environment and experiences to foster deep learning and lasting brain connections. These connections encourage development through authentic instructional programming that considers the context of the child and their construction of knowledge. Through scaffolding, the effective educator guides this development and the abilities of the child emerge.

Although educators often cannot change the trauma children may be experiencing, it is important for early childhood educators to recognize and understand the signs of trauma. Educators can connect families to services that can help alleviate the effects of trauma as well as address and minimize its impacts in the classroom. Because trauma can have long-term impacts on brain functioning, trauma-informed practices have become a hallmark of publicly funded prekindergarten programs. These programs focus heavily on the socio-emotional development of children in recognition of its profound impact on learning and well-being. Often, traumas from a child’s or family’s past may manifest as behavioral or learning difficulties in the classroom. A safe and healthy learning environment is paramount to successfully guiding the development of children experiencing the effects of trauma. The good news for early childhood educators is that many of the factors that build the foundation of the brain can be positively impacted by our work. Because the brain functions in an integrated fashion, learning and development are also integrated and can impact each other. In short, when we are exposing children to a new word, material, or experience, we are also building their brains. We know that learning is an active process and occurs within the context of social interactions (Levitt & Eagleson, 2018). The choices that educators make in the classroom to actively engage children through play can have a lasting impact on children’s lifelong learning trajectory.

Key Take-Aways

Additional Resources

Brain Development in Young Children: http://changingbrains.org/

Center on the Developing Child: https://developingchild.harvard.edu/science/key-concepts/brain-architecture/

CDC Act Early Checklists: https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/actearly/pdf/checklists/all_checklists.pdf

Trauma and the Developing Brain: https://developingchild.harvard.edu/guide/a-guide-to-toxic-stress/

Virginia’s Early Learning & Development Standards (ELDS): Birth-Five Learning Guidelines. https://www.doe.virginia.gov/early-childhood/curriculum/va-elds-birth-5.pdf

Zero to Three: https://www.zerotothree.org/

References

Center on the Developing Child. (2011). Building the brain’s “air traffic control” system: How early experiences shape the development of executive function. https://developingchild.harvard.edu/

Center on the Developing Child. (2007). The science of early childhood development. www.developingchild.harvard.edu

Gopnik, A. (2009). The philosophical baby. Picador.

Childstats.gov. (2018). America’s children in brief: Key national indicators of well-being. https://www.childstats.gov/americaschildren/fam_fig.asp

Graham, J & Forstadt, L.A. (2011). Bulletin #4356, Children and brain development: What we know about how children learn. Cooperative Extension Publications – University of Maine Cooperative Extension. https://extension.umaine.edu/publications/4356e/

Institute of Medicine (IOM), & National Research Council (NRC). (2015). Transforming the workforce for children birth through age 8: A unifying foundation. http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Reports/2015/Birth-To-Eight.aspx

Jones, D. E., Greenberg, M., & Crowley, M. (2015). Early social-emotional functioning and public health: The relationship between kindergarten social competence and future wellness. American Journal of Public Health, 105(11), 2283–2290. https://doi: 10.2105/ajph.2015.302630

Levitt, P., & Eagleson, K. L. (2018). The ingredients of healthy brain and child development. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_journal_law_policy/vol57/iss1/9

Loewneberg, A. (2018). Despite minimum wage hikes, ECE wages stay low. https://www.newamerica.org/education-policy/edcentral/despite-minimum-wage-hikes-ece-wages-stay-low/

Marrus, N., Eggebrecht, A.T, Todorov, A., Elison, J.T., Wolff, J.J., Cole, L., Gao, W., Pandey, J., Shen, M.D., Swanson, M.R., Emerson, R.W., Klohr, C.L, Adams, C.M, Estes, A.M., Zwaigenbaum, L., Botteron, K.N., McKinstry, R.C., Constantino, J.N., Evans, A.C.,… Pruett, J.R. (2018). Walking, gross motor development, and brain functional connectivity in infants and toddlers. Cerebral Cortex, 28(2), 750–763. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhx313

McCain, M., Mustard, J.F., & McCuaig, K. (2011). Early years Study 3: Making decisions taking action. Council for Early Child Development. https://www.academia.edu/17129326/Early_Years_Study_3_Making_Decisions_Taking_Action

National Research Council (US), & Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Integrating the Science of Early Childhood Development. (2000). The developing brain. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK225562/

National Scientific Council on the Developing Child. (2004). Children’s emotional development is built into the architecture of their brains. Working Paper No. 2. https://developingchild.harvard.edu/resources/childrens-emotional-development-is-built-into-the-architecture-of-their-brains/

National Scientific Council on the Developing Child. (2004). Young children develop in an environment of relationships. Working Paper No. 1. https://developingchild.harvard.edu/resources/wp1/

National Scientific Council on the Developing Child. (2007). The science of early childhood development. https://46y5eh11fhgw3ve3ytpwxt9r-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Science_Early_Childhood_Development.pdf

National Scientific Council on the Developing Child (2012). The science of neglect: The persistent absence of responsive care disrupts the developing brain. Working Paper No. 12. https://developingchild.harvard.edu/resources/the-science-of-neglect-the-persistent-absence-of-responsive-care-disrupts-the-developing-brain/

Rosanbalm, K. D., & Murray, D. W. (2017). Promoting self-regulation in early childhood: A practice brief. Opre Brief #2017-79.

UNICEF ECARO & ISSA. (2016). Module 1 The early childhood years: A time of endless opportunities. https://www.issa.nl/sites/default/files/pdf/Publications/cross%20sectoral/Resource%20Modules%20for%20Home%20Visitors%20Module%201.web_.pdf

The Urban Child Institute. (2019). Baby’s brain begins now: Conception to age 3. http://www.urbanchildinstitute.org/why-0-3/baby-and-brain

Image Credits

Figure 2.1: Bryanna Adams and Kalyca Schultz. “Neural Connections in Early Childhood.” CC BY 2.0.

Figure 2.2: Dale Dulaney and Kalyca Schultz. “Human Brain Development by Age.” CC BY 2.0.

Figure 2.3: Kalyca Schultz. “Factors Influencing Brain Development.” CC BY 2.0.

Figure 2.4: Kalyca Schultz. “Serve and Return.” CC BY 2.0.

Additional Images

Image, Section 2.2: Longwood University. [Child with Books] CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Image, Section 2.2: Longwood University. [Child Responding in Classroom Setting] CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Image, Section 2.2: Lucy La Croix. [Bird] CC BY 2.0.

Image, Section 2.3a: Longwood University. [Early Childhood Educator Interacting With Child] CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Image, Section 2.3 & 2.4: Lucy La Croix. [Branch] CC BY 2.0.

Image, Section 2.4: Longwood University. [Serve and Return in Play] CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.