3. Examining Theories that Support Literacy Development

“Teaching can be likened to a conversation in which you listen to the speaker carefully before you reply.”

-Marie Clay

3.4 Ecological/Contextual Theories

Opening Vignette: A Teacher’s Morning

3.1 Introduction

The understanding of theory enables educators to consider the ways children are exposed to and interact with language. Educators apply this knowledge to enhance teaching ability and support literacy learning. In the vignette above, Ms. Tori carefully considers a variety of ways to stimulate children’s language development. She uses picture cues, written words, songs, and books to draw on the children’s prior knowledge and introduce new concepts. Ms. Tori considers the age and stage of the children as well as how her practices foster literacy. She considers what the children already know, the concepts they are learning, and the concepts she wishes for them to learn. These practices are based on broader behaviors, skills, and concepts that explain why and how children grow and develop. It is not enough to merely provide experiences for children, we should have a rationale for why we engage them in certain practices. Theory gives us a framework and a logic for our practices. Theories help us to organize the knowledge we have, and they help us to make predictions about what might occur in the future.

Figure 3.1 Developmental Theories

Some theories focus on the skills reflected by children as they engage with the world and move through developmental stages (constructivist theories). Other theories focus on the broader context of the child (ecological/contextual theories), and some focus on the child’s construction of knowledge while also focusing on the immediate surroundings (sociocultural/cooperative theories). Using theory as a framework builds our scientific understanding of how children grow and develop. The major developmental theories covered in this chapter have been widely used both to verify and refute ideas and to create road maps for early learning environments and practices. Each section in this chapter discusses a broad theory of cognitive development and then a specific theory focused on literacy development. This chapter will explore the following questions:

What theories focus on the child’s skills and behaviors?

What theories focus on the child’s skills and behaviors?

What theories focus on the child and the immediate environment?

What theories focus on the child and the immediate environment?

What theories focus on the wider context?

What theories focus on the wider context?

3.2 Constructivist Theories

3.2 Constructivist Theories

Constructivism emphasizes the individual child and defines indicators of development as the child continues to grow. Children actively construct knowledge based on their stage of development and previous knowledge. As children engage with their environment, they create internal mental structures to comprehend their experiences (Piaget, 1962). Constructivism may also present children’s growth and development as a series of progressive stages. Stage theories help educators recognize children’s accomplishments, anticipate areas of growth, and provide intentional literacy experiences. Piaget’s cognitive developmental theory examines a child’s developmental stage and how they acquire and categorize information internally (Piaget, 1962). Pertaining to emergent literacy progressions, Frith’s theory of reading acquisition presents stages of development as young readers acquire an awareness of alphabetic systems (Frith, 1985).

3.2a Piaget’s Cognitive Developmental Theory

Jean Piaget’s cognitive developmental theory is a form of constructivism. According to cognitive developmental theory, children construct their own learning through interactions and experiences in the environment. Piaget (1962) argued that we are constantly organizing our world by categorizing information and determining ways of applying this information. In the vignette above, Ms. Tori has created an opportunity for children to access the categories of information they have already acquired (e.g., apples are red, green, and yellow) and use this knowledge to engage in discovery play in the apple orchard center.

Several key concepts are important for understanding Piaget’s theory. The units we use to organize our understandings are called schemas. Schemas include not only a concept like “birds fly,” but all of the associations used to develop the concept through past experiences. Piaget believed that we form our schemas through a process called adaptation, which allows us to create categories and subcategories for emerging schemas. There are two types of adaptation: assimilation and accommodation. Assimilation means that we take new information and squeeze it into an existing schema. This can happen whether it makes sense or not, such as trying to fit a peg into a hole, whether it is square or round. Accommodation literally means to make room for something. For example, when most people have houseguests, they accommodate them by altering their sleeping and eating arrangements and their schedules. Assimilation would suggest that hosts told the guests to forage in the fridge for themselves, find a sleeping bag, and figure out where to sleep. Assimilation makes no room—the schema does not change. But accommodation means that there is now room to create or understand something in a new or different way. The process takes place as a result of disequilibrium, which reflects the state a child is thrown into when they receive information that is new. Humans generally experience disequilibrium as uncomfortable, so we generally try to stay in a state of equilibrium, a comfortable cognitive state, until or unless we are exposed to new information that does not fit into our existing schema (Piaget, 1962).

Vignette: Broken Birds

Three-year-old Li has developed a schema that birds fly. This is a reasonable schema based on Li’s experience seeing birds fly in her neighborhood and places she has visited. Today she visited the zoo with her classmates and saw ostriches for the first time. After observing the ostriches, Li turned to her classmates and said, “The birds are broken.” She had noticed that they do not fly. Because Li already has a schema “birds fly” and the non-flying birds have thrown her into disequilibrium, Li has decided that the birds are broken. She has NOT decided that the schema is incorrect. Thus, she has assimilated the ostriches in the “birds fly” schema, with a bit of a footnote that these birds are broken. This allows Li to return to a state of equilibrium as she has assimilated the new information. It takes multiple exposures to a violation of our expectation, or multiple instances of disequilibrium, in order for us to choose to accommodate new information and create new schema. Later that day, Li visited chickens who cannot fly high in the air. Perhaps that second time, she labeled them broken birds or she might have started to consider that some birds do not fly. The third time, Li visits the penguin house and sees definitive evidence that some animals, who are clearly birds, do not fly. At the point where Li creates a new structure that divides birds into “birds that fly” and “birds that do not fly,” she has engaged in accommodation. This is crucial for all forms of cognitive development and has numerous applications to literacy learning when children must decide on the rules and usage of language in all its forms and when they engage in communication to express themselves about the world around them.

Piaget also developed a set of four stages, with individual substages, to map out a range of expected, observable behaviors for children (1962). The sensorimotor stage closely corresponds with infancy and toddlerhood. The preoperational stage is associated with preschool years. The concrete operational stage covers the elementary years, and the formal operational stage applies to adolescence and adulthood. These constructs are outlined in the chart “Piaget’s Stages” (see Table 3.1) and help us to formulate ideas about what would be expected for children at particular ages. Understanding the ages and stages delineated by Piaget (see Table 3.1) helps us to consider the importance of sensory experiences for infants and toddlers.

Table 3.1 Piaget’s Stages

Piaget’s Stages of Cognitive Development

|

Stage |

Approximate Age Range |

Characteristics |

Example |

|

Sensorimotor |

Birth to about 2 years |

The child experiences the world through the fundamental senses of seeing, hearing, touching, and tasting. |

Children may put new objects in their mouths (e.g., the parent’s cellphone). |

|

Preoperational |

2 to 7 years |

Children acquire the ability to internally represent the world through language and mental imagery. They also start to see the world from other people’s perspectives. |

Children start using words and phrases to communicate their desires (e.g., “cookie”). |

|

Concrete Operational |

7 to 11 years |

Children become able to think logically. They can increasingly perform operations on objects that are only imagined. |

Children can tell the difference between their own perspective and another person (e.g., “I can see out of the window, but you cannot.”). |

|

Formal Operational |

11 years to adulthood |

Adolescents can think systematically, can reason about abstract concepts, and can understand ethics and scientific reasoning. |

Children can consider hypothetical situations (e.g., What if I need something in an emergency and there is no adult to ask?). |

With regard to language development, parents and educators are encouraged to sing, talk, and tell stories to children; we couple that with cradling a child or clapping our hands together. We know that children in the sensorimotor stage are learning about their world by touching and being touched, sniffing items, putting everything in their mouths, looking around, and listening with avid interest. Children use these experiences to create schema to apply to the world around them and this fosters their ability to communicate orally and start to perceive symbols. For example, when a child builds a tower of blocks, they start to learn how many blocks can be stacked along with efficient strategies for stacking them. At that point, they can then add blocks to their mental schema for items that can be stacked on top of each other. This knowledge then creates space for a child to use language to express their zeal (or disappointment) in how the block-stacking is going and to beckon others to join in.

Upon entering the preoperational phase, children use symbolic thinking—including language—to communicate their thoughts and ideas. They were able to do so during the sensorimotor phase by indicating and pointing and using some language, but in the preoperational phase, they do so with complexity. Additionally, in the preoperational phase, they can use language to express thoughts about objects or people that are not immediately present. An older infant may point at the elephant while at the zoo, but a preschooler may talk about the elephant they saw at the zoo on a previous day. This greater sophistication reflects children’s ability to engage in symbolic thinking. Children in the preoperational phase need opportunities to develop their increasingly complex language. Providing opportunities for children to engage in pretend-play, participate in social conversations, and use language to solve tasks promotes children’s use of complex language.

3.2b Frith Theory of Reading Acquisition

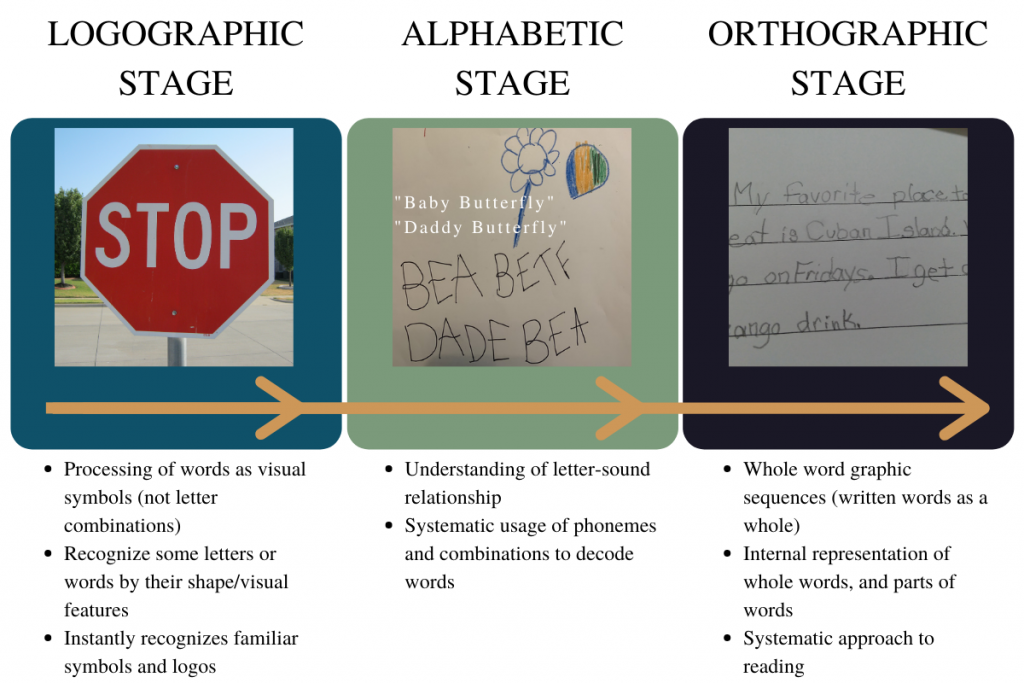

Literacy experts also use a stage model to describe children’s literacy progressions. Although the various stage models of reading have some distinctions and focus on different elements of reading processes, they all share an approach which focuses on children moving from one stage to another with increasing complexity and include features that build on the previous stage. One literacy model is Uta Frith’s theory of reading acquisition. In Frith’s theory, children acquire literacy by moving through particular stages that are developmental and associated with both age and experience. Frith includes three stages of reading acquisition in her model (see Figure 3.2). The first stage, the logographic stage, is characterized by instant recognition of symbols, images, or words. Children demonstrate emerging logographic understandings when they read out familiar logos like Target’s bullseye or McDonald’s golden arches. In the second stage, the alphabetic stage, children begin to use letter symbols to represent the sounds they hear in individual words. Children in this stage demonstrate an emerging understanding of sound and symbol relationships, such as writing /kt/ for cat. The child may hear the beginning sound and ending sound of cat, but the internal vowel sound is not yet recognized. These early approximations demonstrate that they can hear sounds and represent them, but not always completely or correctly. The third stage, the orthographic stage, involves the internalization of spelling patterns and children begin to recognize and reproduce words with increasing automaticity. In this stage, readers do not need to sound out familiar words, though they pause when confronting new words or letter combinations. For example, a child may quickly read the word “kick” but pause to consider how to read the more complex word “knife” because the /k/ is silent. In each of these stages, children master greater complexities of thought and language and teachers must adjust their approaches in order to best foster the child’s growth (Frith, 1985).

Figure 3.2 Frith Theory of Reading Acquisition

Constructivist stage models have many iterations that metaphorically look like stair steps, a spiral, or an increasing sloped line. But, in every case, the image implies that the child is acquiring new and unique skills that capitalize on the previous point and move the child to the next point. The stages are successive and developmental, beginning in infancy. As children master each successive stage, they still retain the skills they attained in previous stages. Literacy stage theories acknowledge that before children can read the list of what is for sale at the orchard, they benefit from repeated exposure to environmental print, letters, letter sounds, and other literacy experiences. This is why intentional educators (like Ms. Tori) use picture cues next to the words on the list of what is available for purchase in the orchard shop. Deliberate actions like this support children’s emergent literacy and honor the developmental nature of the process.

Piaget’s and Frith’s stage theories place an emphasis on seeing the child move forward from one set of capacities to the next more complex set of capacities. Both Piaget and Frith emphasize the process of observing what the child’s behaviors and skills reflect about their thinking. This approach is helpful for educators because it fosters an understanding about where the child is and gives a map for where the child needs to progress next.

3.3 Sociocultural Theories

Sociocultural theories bridge the gap between constructivist approaches and ecological approaches by emphasizing cooperation. These theories emphasize the immediate environment and include educators’ analysis of children’s observable skills and behaviors to present children with the next valuable learning moment. Children develop language skills individually, but they do so within a cooperative learning context as peers, family members, teachers, and others engage, support, and teach them. Vygotsky’s sociocultural learning theory is notable for focusing on what the child can do, while also suggesting that a child’s learning is supported when the right amount of instruction is provided at the right time. Marie Clay’s theories and definitions of emergent reading provide us with a framework for understanding individual children’s prior knowledge and readiness for different literacy experiences. These theories focus on the interactive nature of the child’s capabilities, experiences, and interactions with others.

3.3a Sociocultural Learning Theory

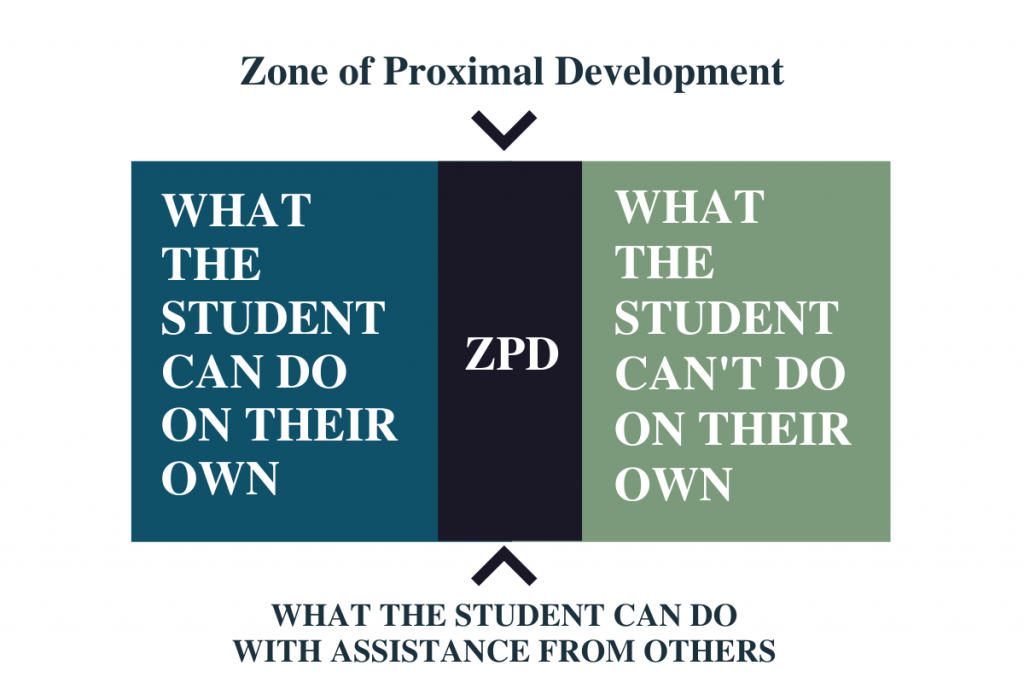

Vygotsky’s sociocultural learning theory emphasizes the social aspect of children constructing their learning (1986). Vygotsky believed that cognitive growth was a result of interactions between people, after which a child internalizes learning. According to this theory, children learn most effectively by engaging meaningfully with someone who is more experienced. Vygotsky developed the concept of the zone of proximal development. He defines it as “the distance between the actual developmental level as determined by the independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem solving” (Vygotsky, 1978, p86).

Figure 3.4 Zone of Proximal Development

Vygotsky recognized a more knowledgeable other could be another child, a family member, a teacher, or anyone who can provide some support for a task. The support itself is called scaffolding. Construction workers, painters, and others use physical scaffolds when they work to reach areas beyond their abilities if merely standing on the ground. In this same way, the support of a more experienced peer giving guidance or direction creates a support for the child to be able to construct their own learning. As a child masters a task, they need less scaffolding and eventually the scaffold disappears (Vygotsky, 1978). For example, many young children have help in learning to wash their hands. An adult may show the child how to acquire the soap, rub their hands vigorously, and rinse. Over time, children need less help with the task, and the scaffold is removed as children are able to wash their hands independently. Children are in progressive zones of proximal development when they are still needing some guidance to wash their hands. Vygotsky placed great importance on the social experience, which provides the scaffold. This theory allows for the notion that children construct their learning, but it also emphasizes that construction requires some help from others.

Pause and Consider: Is Speech the Chicken or the Egg?

Read the following passage examining the differences between Piaget’s and Vygotsky’s conceptualizations of children’s oral language. This creates an interesting chicken-and-egg dilemma with regard to language development. As you read, think about how each theoretical stance resonates with you.

With regard to language, the differences between the approaches of Piaget and Vygotsky can be understood by looking at one aspect of oral language. Children can often be observed engaging in a running stream of commentary as they play and solve tasks. Piaget referred to this action as egocentric speech while Vygotsky termed the practice private speech. The difference in naming reveals what each theorist believed about language and cognitive development. Piaget indicated that egocentric speech was an additional marker of egocentrism, a hallmark of the preoperational period (Piaget, 1962). Egocentrism means that children’s capacity for perspective-taking or understanding another person’s point of view is not yet developed. Piaget argued that egocentric speech reflects the developmental stage the child is in. He reasoned children speak aloud to themselves in this stage because they are unable to understand or perceive that another person is hearing them. Vygotsky indicated it is not merely a lack of perspective-taking that causes children to talk to themselves, but that children do this because they are trying to solve tasks (Vygotsky, 1978). For example, children frequently talk to themselves when they are learning to tie their shoes. Vygotsky indicated that private speech never truly disappears, but instead goes underground as children grow older. It is true that while most adults will not talk to themselves in public, many people will refer to speaking out loud when working through a hard task, such as being lost in traffic or trying to create something complex. Both theorists agree that perspective-taking is limited in this stage, but where Piaget says that egocentric speech is merely a reflection of the child’s development, Vygotsky says that private speech is being actively used as a tool.

Is our language resultant from our cognitive development, or does language lead our cognitive development? Is it possible that both of these approaches are true?

3.3b Marie Clay’s Emergent Literacy Theory

Marie Clay’s emergent literacy theory recognizes a close relationship between the instructional scaffolds used by educators to promote young children’s emerging reading, writing, and oral language skills (Clay, 1991). Drawing on the work of Vygotsky, Clay argues, “The essence of successful teaching is to know where the frontier of learning is for any one pupil on a particular task” (Clay, 1991, p. 65). In this way, Clay extends the value of understanding where an individual child’s zone of proximal development is so that educators take advantage of learning spaces to enhance a child’s literacy learning (p. 65). Clay’s emergent literacy instructional practices underscore the interactions between educators and children and focus on the social supports and contexts children and educators co-create.

Clay recognizes children construct their learning within the context of their own developmental histories, prior knowledge, and previous experiences with complex tasks (Clay, 1998). The focus of emergent literacy then is on the ways that children process information and the subsequent strategies that children learn to use to solve a problem. Moreover, as a member of the early learning community, educators encourage children to share the learning insights they achieve so they, in turn, become valuable literacy resources for their peers (Clay, 1991). Clay embraces teacher scaffolding as a valuable support for children’s literacy learning and views teaching as an interaction between the child and the educator (or other expert). Thus, it is important to have clear instructional approaches that support the child’s ability to discover and use strategies to support their learning with regard to the knowledge that literacy development is unique for each child (Clay, 1998). Understanding emergent literacy approaches means that teachers consider the opportunities that children have had to complete the tasks set before them including their access to previous experiences and prior knowledge. In other words, whether children will choose to replicate creating an apple pie by using beige pom poms, a circle felt crust piece, and a pie tin may depend upon whether they have ever seen anyone create an apple pie from scratch.

3.4 Ecological/Contextual Theories

3.4 Ecological/Contextual Theories

Ecological theories emphasize the child’s system and context. Ecological theories of human development focus on the interrelationships between broader environmental systems and their impact on a child’s development. In contrast to the theoretical approaches presented earlier in the chapter, ecological theories look more broadly at the complex levels of the child’s environment and how this impacts learning. Bronfenbrenner’s ecological theory examines the social resources and relationships that directly and indirectly impact a child’s development. Bronfenbrenner focuses on multiple environments of the child, including the contexts of home, neighborhood, community, and culture (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). Friere’s critical literacy theory focuses on understanding the social, cultural, and political contexts of learners (Friere, 1985). These theories take an ecological approach as they are focused on understanding the child in the backdrop of time, place, and circumstance.

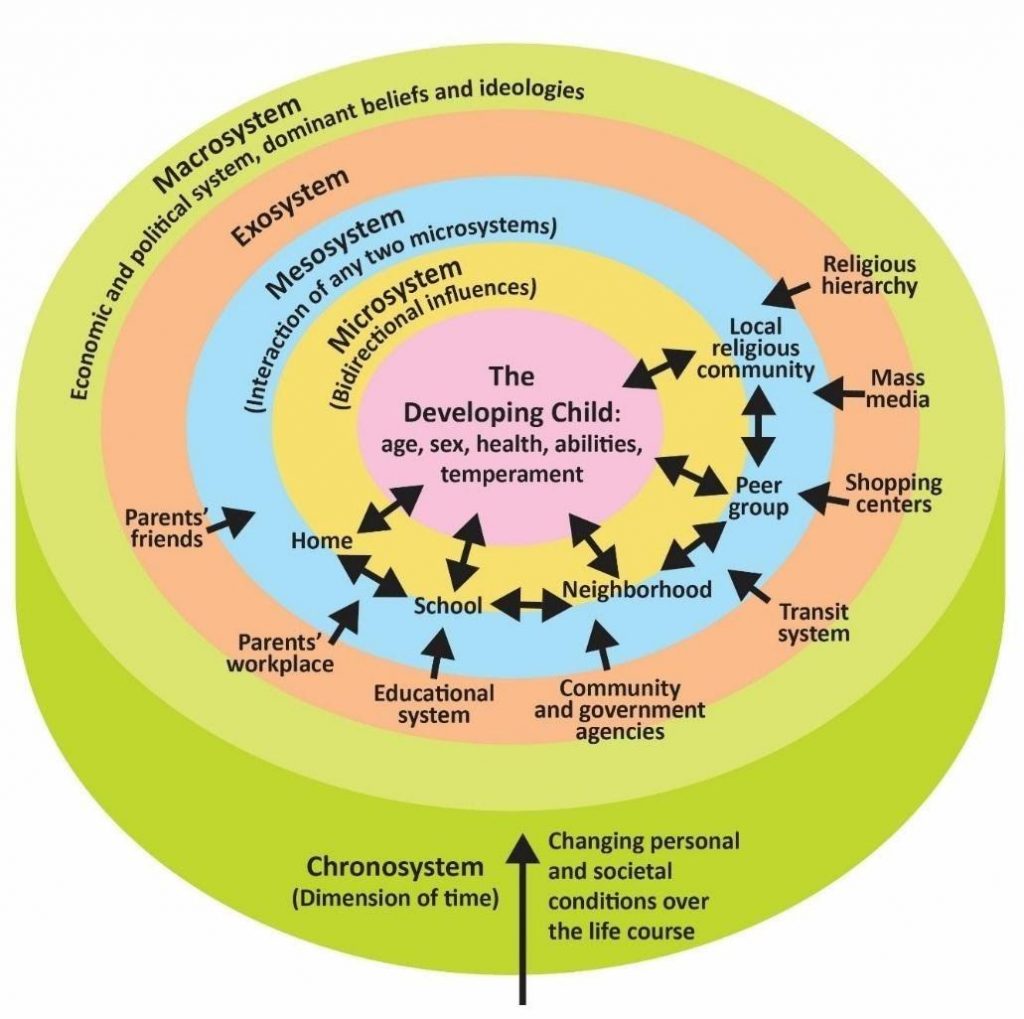

3.4a Ecological Theory of Human Development

The ecological theory of human development emphasizes the contextual interrelationships that exist between individuals, families, the physical environment, the community, and the cultural norms and values of a society. Each of these relationships exerts contextual influence on the individual and is depicted by concentric circles embedded within one another. The nested spheres of influence are represented in the graphic “Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems” (see Figure 3.6) and include the microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, and the macrosystem, with each system based on a greater understanding of influence (Bronfenbrenner, 1979).

Figure 3.6 .Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems

The microsystem includes the interaction a child has in their immediate surroundings. This includes the child’s home and the early learning setting as well as other environments that are consistent and immediate. The interaction between the parent and the child or the teacher and the child forms a microsystem. The mesosystem brings together two settings containing the child. For example, when the early learning teacher and the parents interact, it is taking place in the mesosystem. The exosystem is external to the child, although it influences the child indirectly. The exosystem consists of areas the child does not enter. Examples of the exosystem include the parent’s workplace. Yet, the parental workplace influences the child because it influences the parent, which subsequently affects the interactions between parent and child. Consider, for example, how children and families are impacted differently depending on whether or not the workplace provides access to health care, sick leave, or family leave when needed. The macrosystem consists of the norms and mores that influence culture and customs. These beliefs, expectations, and rules underlie the activities and institutions that constitute our everyday lives. For example, policies around mandatory school attendance were created in the macrosystem and influence jurisdictions (also in the macrosystem) to provide schools for the community (exosystem), for families to enroll the child (mesosystem), and for the child to attend (microsystem). At each of these junctures, there are interactions taking place in the various systems indicated and the systems ripple in and out accordingly. Ripple out occurs as the child has needs, the family responds, the local environment reacts, and social change can occur. In some places, early learning centers open at 5:00 am to accommodate super-commuters. This is an example of how the needs of the child and family create change in the community. Other times, larger policies affect whole communities or families in ways that impact their practices. For instance, when airbags were required in new cars (macrosystem), companies started installing them (exosystem), and families stopped putting car seats in the front seat and instead put the child in the backseat.

As the child interacts with others in the supportive context, the child is exposed to new discrete language skills, such as vocabulary. In the Northern Virginia area, many children are familiar with the word “pentagon” and are aware it has five sides, even before this is introduced as a vocabulary word. The Pentagon, which serves as headquarters for the United States Department of Defense, is an important military, political, and economic presence in the Northern Virginia area (macrosystem). It is also a workplace for some families (exosystem). The Pentagon’s distinctive, five-sided shape is visible from several major roads in the area and a child might easily see it from the car, view it on a tour, or hear others speak about it (mesosystem). This regular exposure influences the words that adults or peers use while regularly interacting with the child (microsystem), and this influences a child’s likelihood of hearing the word, “pentagon.” As a result, children comprehend and use the word “pentagon” earlier than some peers in a different part of the country or state.

The ecological approach, similar to the nested literacy model, looks at the totality of language experience over time. Just as the branch and tree provide the context for the bird in its nest, children’s wider backdrop for their experiences influences what they learn to value and what they learn to master. The “Pentagon” example focuses on vocabulary, but the same principle applies for other discrete skills such as phonological awareness and alphabetic knowledge. Each time the child masters a new discrete skill, it ripples out and interacts with the wider concepts of language development (receptive and expressive language), reading, and writing. This builds the capacity to think and understand. Each time a child is exposed to the wider concepts of language, writing, and reading, it helps to foster abilities in the areas of the discrete skills. Indeed our discrete skills and language concepts are connected in much the same way that microsystem interactions are. It is difficult to say that speaking leads to reading or that reading leads to speaking. It is more accurate to say that they are transactional and interactive and develop concurrently.

Our understanding of language development must take into account environmental aspects beyond the immediate situation containing the child. This means that the literacy interactions that a child experiences in their environment influence the family and vice versa, causing influential ripplings in and out. Children first learn what is familiar and contextual. Development is influenced by multiple systems, including the family, school, neighborhood, and larger ecologies that encompass more immediate systems (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006). These systems are the context in which children learn.

3.4b Freire Critical Literacy

Paulo Freire (1985) defined critical literacy as the capacity to analyze, critique, and transform social, cultural, and political texts and contexts by having a thorough understanding of the experience of the student. Freire went on to suggest that in order to truly reach students, one must be aware of their problems, struggles, and aspirations, while also considering the power dynamics implicit in the ideas and materials they are exposed to and the relationships they develop. Additionally, these understandings should be followed by a reciprocal exchange and a willingness for action in ways that would meet the learner where they are.

Critical literacy acknowledges teachers have the power to send implicit messages about the importance and meaning of some information above others. Teachers as decision-makers determine the value of particular lessons, goals, materials, and the structure of the learning day. Children receive feedback about the relative importance of ideas within teacher and classroom interactions. These differences are contextual and socially constructed, even as they are transmitted back and forth between speaker and listener, between environment and child, and among each of these characters as they move through their day (Luke, 2012).

For example, a critical literacy approach prompts us to stop and acknowledge our decision to choose the apple orchard shop in the opening vignette as our theme for the dramatic play area. We are making choices as educators about the types of play contexts that have value and the types of vocabulary that should be introduced. For example, Ms. Tori may also choose to include a picture card that says “manzana,” the Spanish word for apple, in order to support the home language development that she has already identified in the group of children she teaches. Even more broadly, critical literacy challenges us to question the value of the apple orchard center for learners. Would an apple orchard dramatic play area hold the same relevance for children in south Florida as it would for children in northern Michigan? The answer is, it depends. When answering questions about instructional practices, critical literacy asks us to consider: What is the intended goal? What are the children’s interests and how do they connect to their real-world experiences? If not, what would make these practices relevant and impactful for the children? Are the children given only the materials for apple pie, and might it be relevant to include materials for other types of apple desserts, such as apple empanadas? What types of play would be acceptable in this play area? Critical literacy challenges teachers to always consider whether the educational environment and experiences they choose allow children to feel seen and heard as they acquire knowledge.

3.5 Using Theory in Practice

Theories matter because they inform our practice. When we stop to evaluate if a literacy activity seems appropriate for the age and stage of the child, we are grounding our practice in a theory (Piaget/Frith). When we set up our classroom with learning stations to encourage children to learn language from one another, we follow a theoretical construct (Vygotsky/Clay). When we stop to ask about the environmental influences on the family and, subsequently, the child’s language development, our practice reflects our understanding of the factors that Bronfenbrenner and Friere spoke about. Understanding the theoretical frameworks that guide our practice helps us to be more effective and intentional in the classroom.

Pause and Consider: Theory to Practice

Key Take-Aways

Additional Resources

Piaget Society Resources for Students: https://piaget.org/resources-for-students/

Critical LIteracy: Promoting Equity in Early Childhood Settings: https://www.hekupu.ac.nz/article/critical-literacy-promoting-equity-early-childhood-settings

Frith’s Model of Reading Acquisition: https://esol.britishcouncil.org/sites/default/files/attachments/informational-page/Frith%27s%20model%20of%20reading%20acquisition.pdf

The Importance of Bronfenbrenner’s Bioecological Theory in the Classroom: http://libres.uncg.edu/ir/uncg/f/J_Tudge_Importance_2017.pdf

Marie Clay’s Literacy Processing Theory: https://readingrecovery.org/reading-recovery/teaching-children/early-literacy-learning/

Paolo Freire Institute for Learning: https://www.freire.org/paulo-freire/

Virginia’s Early Learning & Development Standards (ELDS): Birth-Five Learning Guidelines. https://www.doe.virginia.gov/early-childhood/curriculum/va-elds-birth-5.pdf

Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development and Scaffolding: https://educationaltechnology.net/vygotskys-zone-of-proximal-development-and-scaffolding/

References

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press.

Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. A. (2006). The bioecological model of human development. In R. M. Lerner & W. Damon (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Theoretical models of human development (pp. 793–828). John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Clay, M. M. (1991). Becoming literate: The construction of inner control. Heinemann.

Clay, M.M. (1998). By different paths to common outcomes. Stenhouse

Freire, P. (1985). The politics of education: Culture, power, and liberation. Bergin & Garvey.

Frith, U. (1981). Experimental approaches to developmental dyslexia: An introduction. Psychological Research, 43, 97–110.

Frith, U. (1985). Beneath the surface of developmental dyslexia. In K. Patterson, M. Coltheart & J. Marshall (Eds.), Surface dyslexia. Erlbaum.

Luke, A. (2012). Critical literacy: Foundational notes. Theory Into Practice, 51(1), 4–11. https://doi: 10.1080/00405841.2012.636324

Piaget, J. (1962). Play, dreams, and imitation in childhood. Norton.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind and society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1986). Thought and language. MIT Press.

Image Credits

Figure 3.1: Leslie LaCroix and Kalyca Schultz. “Developmental Theories.” CC BY 2.0, derivative image using untitled image, (https://pxhere.com/en/photo/941148) by unknown author, “Preschool Girl and Boy,” (https://bit.ly/32F4Zgo) by Alliance for Excellent Education, and 070608-F-5217S-001.JPG, (https://bit.ly/3gsZCZP) by U.S. Department of Defense.

Figure 3.2: Kalyca Schultz. “Frith Theory of Reading Acquisition.” CC BY 2.0, derivative image using “stop sign,” (https://www.flickr.com/photos/84388958@N03/7729300102) by Clover Autrey.

Figure 3.3: Kalyca Schultz. “Zone of Proximal Development.” CC BY 2.0.

Figure 3.4: “Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems.” Ian Joslin, LibeTexts, CC BY 4.0. (Retrieved from https://bit.ly/3aFI2OG)

Additional Images

Image, Section 3.2: Lucy La Croix. [Bird] CC BY 2.0.

Image, Section 3.2a: Longwood University. [Constructing Learning] CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Image, Section 3.3: Lucy La Croix. [Nest] CC BY 2.0.

Image, Section 3.3a: Longwood University. [Feedback From Experienced Peer] CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Image, Section 3.4: Lucy La Croix. [Branch] CC BY 2.0.

Image, Section 3.4b : Longwood University. [Teacher Planning] CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.