10. Planning for What’s Next as Emergent Readers and Writers Progress

With Christopher Kidd

“Literacy is a journey, not a race.”

-Bonnie Hill Campbell

10.2 Language- and Literacy-Rich Environments

10.3 Next Steps in Language and Literacy Development

10.4 Language and Literacy Assessment and Instruction Practices in the Primary Years

Opening Vignette: What’s Next for Nukilik

Nukilik just turned 5-years-old in January and has started showing increased literacy proficiency. Ms. Ling reflects on her assessment data on Nukilik’s language and literacy growth over the past 5 months and feels that he is moving out of the emergent phase of literacy development and is ready to learn new skills. Ms. Ling has noticed that Nukilik can write his name with ease, draw detailed stories, and write words using invented spelling and some conventional spelling. He writes sentences and will add a sentence when asked questions that help him think about additional details. He is beginning to write about a variety of topics and recently realized that he could entertain his classmates with his make-believe stories. He draws from the books that are read to him to get ideas for his stories.

Ms. Ling has observed that Nukilik holds books correctly and is often seen with a book in the library area. When she reads with him, she has noticed an increase in the number of words he recognizes by sight and that he is attempting to decode some phonetically regular words. During read alouds, Nukilik is becoming more adept at predicting what comes next and is eager to answer questions that Ms. Ling poses to the class. Ms. Ling can also tell that he is becoming more proficient at retelling stories and sharing information from nonfiction texts. She often finds him engaged in dramatic play based on a book she recently read aloud. He has also become quite a conversationalist and enjoys talking with classmates. Ms. Ling has noted that he has started to use increasingly correct grammar when speaking English and is attempting to use vocabulary from the books she reads to the class in his conversations. He also continues to speak in his home language, especially during play, and incorporates words from his home language into his writing.

Ms. Ling is excited about the way Nukilk is using language and how his reading and writing are developing. She recognizes that she can foster continued growth by providing challenging and engaging learning experiences for Nukilik. Based on her assessments of his language and literacy progressions, Ms. Ling realizes that Nukilik is transitioning from emergent to conventional literacy. She knows that she needs to prepare for what comes next for Nukilik to nurture his continued growth.

10.1 Introduction

As children are provided opportunities at home, in the community, and at school to engage in language- and literacy-rich experiences, their literacy knowledge and skills continue to develop. The literacy skills they develop from birth through their prekindergarten years provide a foundation for the development of the conventional literacy skills children need as they become more proficient readers and writers (NELP, 2008). The National Early Literacy Panel (2008) identified conventional literacy skills as “decoding, oral reading fluency, reading comprehension, writing, and spelling” (p. vii). As discussed throughout this textbook, educators play an important role in developing young children’s oral language, emergent reading, and emergent writing development. Educators are also instrumental in meeting children where they are and ensuring that they continue to make positive progress along the developmental continuum, including children who may be progressing in advance of their peers. Therefore, it is important for educators to understand what is next as emergent readers and writers progress. When educators know what is next, they are better able to plan and implement assessment and instruction that promotes children’s oral language development and supports the development of conventional literacy skills. Therefore, this final chapter will explore the following ideas:

How do young children develop an understanding of language and literacy during their later prekindergarten and early primary years?

How do young children develop an understanding of language and literacy during their later prekindergarten and early primary years?

How do young children progress as they become more proficient readers and writers?

How do young children progress as they become more proficient readers and writers?

What can early childhood educators do to support young children as their language and literacy knowledge and skills continue to develop?

What can early childhood educators do to support young children as their language and literacy knowledge and skills continue to develop?

10.2 Language- and Literacy-Rich Environments

10.2 Language- and Literacy-Rich Environments

Language- and literacy-rich home, community, and school environments continue to be important as children transition from their prekindergarten years to their kindergarten and early primary years. At home and in the community, children continue to observe and engage in language and literacy events that develop their oral language and conventional literacy skills. As their language skills progress, they become more active participants in the conversations that surround them. This, in turn, supports the further development of their vocabulary and conversational skills, especially in the languages spoken at home and in the community. Likewise, as children become increasingly more capable of reading print in their environment, they might read an “I love you” text from a grandparent, a birthday card from a neighbor, or the title of a favorite television show or movie. In addition, books and e-readers play an important role in their language and literacy development as they listen to increasingly more complex texts and begin to read books independently. At the same time, children’s writing skills become more conventional, which enables them to use writing as a means to make notes to themselves and communicate with family and friends. For example, children might write a reminder about the topic of books they want to check out from the library (e.g., dinosaur books) or create a poster for their door with their name showing ownership of their room (e.g., Clara’s room). They might also create lengthier compositions, such as a story, like the make-believe stories Nukilik shares with his classmates, or information about a topic of interest to share with others.

Similar to their younger years, children come to school enriched by these home and community language and literacy experiences. Educators build upon and add to these experiences by creating a classroom environment that values children’s diverse linguistic and cultural backgrounds and provides meaningful opportunities to engage in language and literacy activities. As children transition from prekindergarten to kindergarten classroom contexts, exposure to rich language and literacy environments continues to be important. Children need opportunities throughout the day to express their ideas orally and in writing and to interact with diverse texts. Print-rich environments, access to a plethora of texts, and experiences writing for a variety of purposes work in complementary ways to support children’s early literacy.

10.3 Next Steps in Language and Literacy Development

10.3 Next Steps in Language and Literacy Development

As children transition from prekindergarten into kindergarten and the early elementary years, their language and literacy knowledge and skills continue to develop. Their communications become more complex, and they become increasingly more proficient at speaking, listening, reading, and writing. It is important for early educators to have an understanding of what the next steps are in language, reading, and writing development as they assess children’s progress and plan instruction for young children who are beginning to use conventional language and literacy skills.

10.3a Language Development

Language development in the early years is full of big headlines. Children begin with only the barest ability to communicate their needs by way of their reflexes, unconscious responses, crying, and expressing contentment. As they move through the earliest months and years, they develop greater motor ability in holding up their head, eye gaze, articulation, and using their body to communicate. They make leaps and bounds in their capacities in the early months and years whether verbal or non-verbal. They learn that they have a voice and can use it to share their thoughts or solve their problems. They engage in storytelling, sign language, and non-verbal language. These skills and abilities create and enhance their ability to engage socially in their world.

As children move into the school-age years, they begin to further refine their language development. Each of the parts of language becomes more fluid and adult-like. Their phonology is enhanced and children begin to pronounce their words with greater ease as their motor abilities progress. Children further learn grammar rules through self-correction, direct instruction, and supportive recasting. Their understanding of semantics grows over time as they start to distinguish between a teasing tone or the different meaning of a word in a different context. Children refine their ability to understand pragmatic rules of language as their social world expands, and they learn how to communicate differently in a variety of circumstances. Sebastian, who was introduced in Chapter 7 as crying out “Cabasasa” when he sees a pumpkin, will enhance his abilities in the preschool years and beyond. He eventually learns to say “calabaza” as his articulation (an area of phonology) improves. He will also expand his vocabulary and pronunciation as he learns the meaning and pronunciation of the word, “pumpkin.” By the end of preschool, he can use calabaza and pumpkin interchangeably as his pragmatic understanding allows him to switch between languages. Moreover, he can use either word in grammatically correct sentences. Finally, Sebastian will be able to use either pumpkin or calabaza in a joke or in other ways that reflect greater maturity in his understanding of semantics.

The primary school years are focused on creating opportunities for children to practice skills they have already learned about productive and expressive language and to expand on these concepts. It is expected that children can communicate when they enter kindergarten. In their primary years, their informal conversational skills continue to grow as they interact with adults and peers (VBOE, 2017). They become more adept at initiating conversations, listening to others, taking conversational turns, staying on topic, and following the rules of conversation. They become more collaborative conversationalists and talk about a variety of topics and texts as they converse and work with others. They use complete sentences as they talk and learn to use appropriate phrasing, intonation, and voice levels for the situation. They become more proficient at using direct requests to express their needs and at asking why and how questions to get and clarify information as well as to ask for help. In addition, they are better able to follow one- and two-step directions.

Educators also expect that children will possess a wider and deeper vocabulary at the end of that year. They become more fluid in expressing themselves and more adept at interpreting the messages of others. These increased understandings are fundamental to allowing children to know that they have a voice that can be shared orally or through their writing. This is also essential to helping children receive language through other people’s thoughts, whether expressed by reading or by communicating through speech or other forms of communication, such as gestures and sign language.

Throughout their early years, children have made leaps and bounds in using symbolic thinking to learn how to communicate, whether verbal or non-verbal. They have learned to express themselves as they interact with books, media, and other print materials and engage in storytelling, dramatic play, choral and echo recitation, and other forms of verbal and non-verbal expression. They have learned they have a voice and can share those thoughts and understand those thoughts via oral literacy, sign language, and non-verbal language. These skills and abilities create and enhance their ability to engage socially in their world.

10.3b Reading Development

The transition from emergent reading to more conventional reading is an exciting time for young children, families, and educators. During this transition, children, like Nukilik, begin to use their knowledge of letter-sound correspondence to pronounce words more consistently. This is an important progression because being able to decode words contributes to children’s oral reading fluency and their comprehension of the text. When children read fluently, they are able to read with speed and accuracy as well as with expression. Becoming proficient at decoding and more fluent when reading orally supports children’s reading comprehension because they are able to focus their attention on constructing meaning rather than on the task of recognizing words. Children comprehend text when they construct meaning as they read and make connections to their prior knowledge. They draw upon their existing vocabulary to understand what they read and develop new vocabulary as they encounter new words and concepts. Children’s developing vocabulary, decoding skills, and oral reading fluency support their comprehension of text, which is the goal of reading (NELP, 2008).

As children read and write in prekindergarten, code-related instruction (i.e., decoding words when reading and encoding words when writing) emphasizes letter-sound relationships (Foorman et al., 2016). For example, children learn that if they see a “b,” they should use a /b/ sound when reading. Likewise, when they hear a /b/ sound, they should write a “b.” During the transition from emergent to conventional reading, educators place an increased focus on word parts and patterns in words instead of individual letters and sounds (i.e., onset/rhyme and digraphs). In other words, children learn to apply what they know about a word pattern to another word. For example, a child might think, “I know the word ‘hat’ and this word starts with a ‘c’ so that says ‘cat’.” Instruction also begins to focus on sight words (i.e., words with irregular spelling patterns) and high-frequency words that are often found in text. In addition, children begin to develop understandings of the role of punctuation as they read and get better at tracking text (i.e., following down to the second line). In this phase, fluency is slow and reading is often word-by-word. As children begin to recognize words automatically and their sight word vocabulary increases, they become more fluent readers and are able to read with increased speed, accuracy, and expression.

Children begin to read simple, predictable text that includes picture supports and words they know. They begin using initial sounds in words when reading and use cross-checking strategies to confirm or disconfirm accuracy. For example, a child reads a word as “bear” but then looks at the picture and says, “Oh wait…that says bird.” Children also begin to use their decoding skills as they read text with words they are able to decode. And they use their sight word vocabulary to further assist their reading. Initially, children may read hesitantly. However, with practice, children become more confident in their skills and begin to believe, “I can read this book!”

During their transition to conventional reading, children begin to apply a variety of comprehension strategies that support their understanding of fiction and nonfiction text (VBOE, 2017). They learn to relate what they are reading to their prior knowledge and previous experiences in order to link their new learning to what they already know. Like Nukilik, they use their prior knowledge, pictures, and text to make predictions about what is going to happen. They also ask and answer questions about the text. In addition, they retell the beginning, middle, and end of familiar stories using story elements, such as the setting, characters, and events. They use the text and pictures to talk about what happens in the story, the characters’ feelings, and the problem of the story. In nonfiction text, they use text features, including pictures, the title, and headings, to get information when reading. As they read, they are able to identify information that is new to them and talk about what they read. In addition, they create mental images of what they read using words and pictures and share their visualizations with others.

The early primary years are crucial in the development of children’s reading as they transition from emergent reading to more conventional reading. During this time, they are developing important decoding, oral reading fluency, and comprehension strategies and skills. They have learned to use decoding skills and sight words to recognize words as they read. They have developed their oral reading fluency as their word recognition becomes more automatic and they learn to read with speed, accuracy, and expression. Most importantly, they are developing essential comprehension strategies that enable them to construct meaning as they read and apply the information in a variety of situations.

10.3c Writing Development

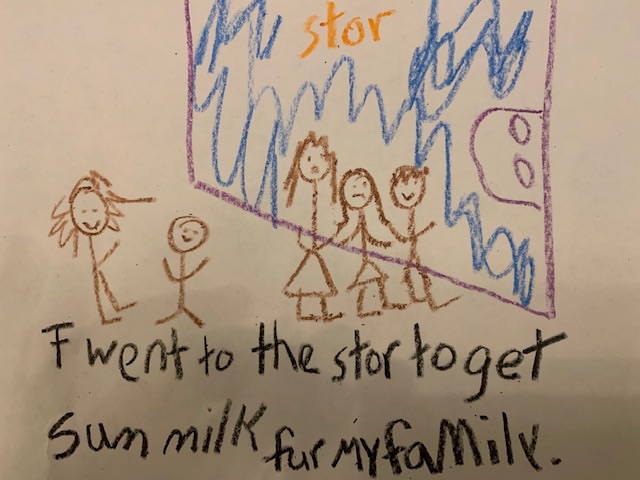

Figure 10.1 Example From a Developing Writer

Children’s understanding of writing as a way to communicate continues to develop as children engage in a variety of language and literacy experiences. As they talk and listen, their vocabularies expand and they learn about the grammar and pragmatics of language. As they read, they gain greater insights into how text works and how authors communicate their ideas through printed text. Children draw upon their expanding vocabulary and their more nuanced knowledge of how print works as they write for a variety of purposes and a range of audiences. A rich vocabulary helps them find just the right words as they write to express ideas, tell stories, share information, and convey opinions. When given opportunities to make decisions about what to write and how to write, they expand their conceptions of authorship and further develop their voice as well as their identity as writers (Kidd et al., 2014).

While writing, children, like Nukilik, use their knowledge of the relationship between letters and sounds to write (encode) words using invented spelling (See Figure 10.1). As their writing progresses, children use more conventional spelling, including phonetically spelled words and sight words (VBOE, 2017). Eventually, they begin to spell most words correctly. At the same time, children become more adept at following the conventions of writing (i.e., capitalization, punctuation, and grammar). They begin to compose simple sentences, including statements, questions, and exclamations, that begin with a capital letter and end with a punctuation mark. They also begin to use capital letters for names. Children’s handwriting becomes more proficient as their fine motor skills develop. They print capital and lower-case letters of the alphabet. When they write in English, they write from left to right and from top to bottom. In addition, they begin to use appropriate spacing between words and sentences. Their writing becomes longer and more complex as they become more proficient writers.

Children also gain a deeper understanding of writing as a process and become more skillful at planning, drafting, revising, editing, and sharing their writing (VBOE, 2017). They begin to differentiate drawing and writing and use their drawing and other planning strategies to intentionally plan their writing. For example, children often draw a picture at the top of the paper to generate ideas for their writing and then use what they drew to write words, phrases, and sentences underneath. They continue to generate ideas as they write and talk about their writing. As they become more proficient, they revise their writing by adding descriptive words or additional sentences. For example, Nukilik drew a detailed picture of the playground that included him swinging on a swing set. He wrote, “I played on the swing.” When he shared his story with Ms. Ling, she asked, “What was it like to swing on the swing?” Nukilik thought about it and said, “It was fun.” Ms. Ling encouraged him to add that detail to his writing. He revised his story by adding, “It was fun. I liked feeling the wind.” Children also begin to edit their writing to correct spelling and to conform to writing conventions. For example, a child might change a period to a question mark after remembering a question needs a question mark. At this time, sharing their writing with others is an important part of the process.

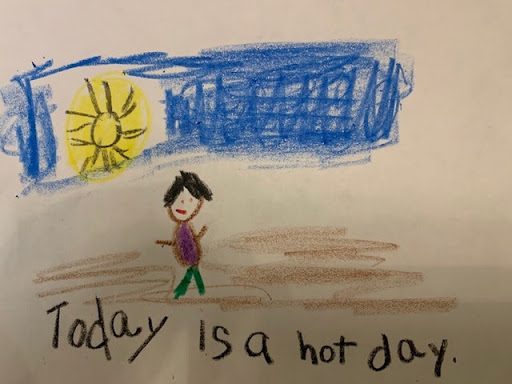

Children begin to expand their writing as they become more proficient writers. During the primary years, they continue to write about their family experiences, but also begin to write more make-believe stories modeled after the books adults are reading to them or they are reading themselves. For example, a child might write about a story about a magical pony or a superhero adventure. Opportunities to write across the curriculum also increase as children write to share information in language arts, mathematics, science, and social studies. For example, children might engage in recording plans for a science experiment, documenting the growth of plants in their classroom, sharing facts about animals, explaining why it is important to take turns, or convincing others to recycle. They also use writing to show their understanding of what they have read and learned across the curriculum. For instance, when children write about the difference between hot and cold, they are showing their understanding or misconceptions of what they are learning about temperature (see Figure 10.2).

Figure 10.2 Today is a Hot Day

As children transition to more conventional writing, writing becomes a vehicle for communicating their ideas with others. During the primary years, children gain a greater understanding of writing as a powerful tool for communicating. They develop their identity and voice as writers. Children understand that, as authors, they have ownership of their writing and can write for a range of purposes and a variety of audiences. In addition, they become more proficient at engaging in writing processes, conforming to written conventions, and using conventional spelling. Their handwriting and use of digital tools, such as touch tablets and computers, also develop considerably during this time. When given meaningful, authentic opportunities to write during the primary years, children can not only develop their writing proficiency, but also their enjoyment of and motivation to write (Graham et al., 2018).

10.4 Language and Literacy Assessment and Instruction Practices in the Primary Years

10.4 Language and Literacy Assessment and Instruction Practices in the Primary Years

Early educators in kindergarten and the early primary grades continue to integrate the ongoing assessment practices described in Chapter 6 and the instructional practices described in Chapters 7, 8, and 9. As children progress, they build upon these practices by integrating additional assessments that help them capture and document children’s growing knowledge and skills. They use what they learn from these assessments to adapt their instructional practices to move children toward conventional reading and writing.

Informal assessment practices remain essential in documenting the children’s early literacy expressions. Educators also begin incorporating additional literacy assessments into their instructional routines. Formal assessments like the Developmental Reading Assessment (Beaver & Carter, 2019) and PALS (Invernezzi et al., 2004) continue to offer insight into children’s progressing literacy skills, including specific information regarding children’s increasing language expressions, phonological awareness, vocabulary knowledge, comprehension, linguistic fluency, and writing. Educators continue to use formal and informal assessments in complementary ways to create holistic understandings of children’s literacy growth. In turn, assessment remains an important practice shaping early educators’ curricular decisions and the literacy opportunities children experience

As children’s language and conventional literacy skills develop, educators and families continue to play an important role in providing children with learning experiences that promote their language and literacy development. To enhance development, educators assess their children and learn more about their strengths and needs. They then use the information they gather to plan and implement instruction intentionally designed to develop children’s language and literacy knowledge and skills throughout the school day and at home. By providing instruction that supports individual children’s language and literacy progressions, educators ensure that each child has opportunities to continue to develop their language and literacy knowledge and skills. These opportunities are provided when educators (a) create an environment that supports reading and writing; (b) build on children’s prior knowledge, experiences, and interests; (c) integrate reading and writing into play; (d) infuse reading and writing across the curriculum; and (e) provide diverse instructional reading and writing experiences (see Table 10.1).

Table 10.1 “Language and Literacy Instructional Practices in the Primary Years”

- Create inviting and accessible spaces for children to read, write, and communicate with each other.

- Provide a variety of reading and writing materials that reflect children’s diversities and encourage curious exploration.

- Display children’s writings and expressions prominently.

- Provide children access to nonfiction and fiction text materials.

- Engage families in children’s literacy experiences.

- Encourage children to use their home languages and integrate their home culture and family experiences into the classroom.

- Access children’s funds of knowledge by incorporating activities that activate children’s prior knowledge.

- Provide experiences that promote conversation and provide authentic reasons to communicate, read, and write.

- Schedule time for reading and writing instruction and provide opportunities throughout the day for children to read and write independently and with support.

- Provide opportunities for children to talk, read, and write with others.

- Model language, reading, and writing by engaging in shared literacy experiences, including read alouds, shared reading, shared writing, and conversations.

- Create authentic purposes for children to read,write, and communicate for a variety of purposes.

- Provide explicit instruction as well as opportunities for children to explore language, reading, and writing.

- Scaffold children’s language and literacy development through intentional interactions that develop their language and literacy knowledge and skills.

- Provide opportunities for children to use listening, speaking, reading, and writing to learn content across the curriculum, including in mathematics, reading, science, and social studies.

- Use children’s conversations and writing to assess their content knowledge.

Key Take-Aways

Additional Resources

Improving Reading Comprehension in Kindergarten Through 3rd Grade: A Practice Guide (NCEE 2010-4038): https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/Docs/PracticeGuide/readingcomp_pg_092810.pdf

Teaching Elementary School Students to be Effective Writers: A Practice Guide (NCEE 2012- 4058): https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/Docs/PracticeGuide/WWC_Elem_Writing_PG_Dec182018.pdf

References

Beaver, J., & Carter, M. (2019). Developmental reading assessment (3rd ed.). Pearson.

Commonwealth of Virginia Board of Education (VBOE). (2017). English standards of learning for Virginia Public Schools. https://www.doe.virginia.gov/testing/sol/standards_docs/english/index.shtml

Foorman, B., Beyler, N., Borradaile, K., Coyne, M., Denton, C. A., Dimino, J., Furgeson, J., Hayes, L., Henke, J., Justice, L., Keating, B., Lewis, W., Sattar, S., Streke, A., Wagner, R., & Wissel, S. (2016). Foundational skills to support reading for understanding in kindergarten through 3rd grade (NCEE 2016-4008). National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance (NCEE), Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. http://whatworks.ed.gov

Graham, S., Bollinger, A., Booth Olson, C., D’Aoust, C., MacArthur, C., McCutchen, D., & Olinghouse, N. (2018). Teaching elementary school students to be effective writers: A practice guide (NCEE 2012- 4058). National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/Docs/PracticeGuide/WWC_Elem_Writing_PG_Dec182018.pdf

Invernizzi, M., Sullivan, A., Swank, L., & Meier, J. (2004). PALS pre-K: Phonological awareness literacy screening for preschoolers (2nd ed.). University Printing Services.

Kidd, J. K., Burns, M. S., La Croix, L., & Cossa, N. L. (2014). Prekindergarten and kindergarten teachers in high poverty schools speak about young children’s authoring (and we need to listen). Literacy and Social Responsibility, 7(1), 50-71.

National Early Literacy Panel (NELP). (2008). Developing early literacy: Report of the National Early Literacy Panel. https://lincs.ed.gov/publications/pdf/NELPReport09.pdf

Beaver, J., & Carter, M. (2019). Developmental reading assessment (3rd ed.). Pearson.

Image Credits

Figure 10.1: Julie Kidd. “Example From a Developing Writer.” CC BY 2.0.

Figure 10.2: Julie Kidd. “Today is a Hot Day.” CC BY 2.0.

Additional Images

Image, Section 10.2: The New School AR. “DSC_0026.” CC BY-NC-SA 2.0. (Retrieved from https://bit.ly/3u4pmja)

Image, Section 10.2: Lucy La Croix. [Nest] CC BY 2.0.

Image, Section 10.3: Lucy La Croix. [Bird] CC BY 2.0.

Image, Section 10.3b: Kathy Cassidy. “Reading to the Kindergarten Students.” CC BY-NC-SA 2.0. (Retrieved from https://bit.ly/3xBhMyq)

Image, Section 10.4: Lucy La Croix. [Branch] CC BY 2.0.