32 A Closer Look at the Curriculum Planning Cycle

Children reveal who they are and how they think through their actions and behavior. How they play with others, how they use materials, and even the types of activities they choose to tell us a story. Each child has their own story to tell and it is up to us, as intentional teachers, to gather essential evidence and artifacts that can be used to inform our decisions on how to best support each child’s learning, growth and development. Curriculum should be thoughtfully planned, challenging, engaging, developmentally appropriate, culturally and linguistically responsive, comprehensive, and likely to promote positive outcomes for all young children.[1] To guide our decision-making and to effectively implement meaningful curriculum we must utilize the Curriculum- Planning Process. Let’s examine and discuss the 4 steps of the cycle.

Step 1: Observation – Looking and Listening

To develop effective curriculum, quality observations must be conducted. Whether spontaneous or planned, formal or informal, in-depth observations provide teachers with an advantage point. With each observation, teachers gain valuable insight that helps them gauge a child’s zone of proximal development, and with that information, teachers can decide on how to best scaffold that child’s learning. Likewise, teachers who conduct ongoing observations discover each child’s baseline knowledge, and with that data, they can develop curriculum that supports children’s play and learning in a developmentally appropriate manner. Furthermore, a teacher who regularly observes can track children’s interests which in turn helps her to select materials and resources that will fascinate, intrigue, challenge and engage the children. Thus, when teachers take detailed notes and record objective facts, they recognize each child’s individual pace, temperament, capabilities, interests and needs. It is with this vital data that they can ultimately meet children where they are at developmentally and map out where they need to go by intentionally setting reasonable expectations and goals.

To truly discover a child’s intent, teachers need to be fully attentive to what children are doing and saying while they are playing and interacting with others. To be fully attentive requires a particular state of mind. Rather than being actively engaged with children or guiding their behavior or directing their play, teachers need to find moments where they can focus on looking and listening . Teachers need to approach each observation with an open mind – free of bias and preconceived notions, and they need to have an open lens to see what children are actually doing. Sometimes we can only look and listen for a brief moment; sometimes we can look and listen for a longer timeframe. Either way, we need to take in all that we are seeing and hearing so that we can discover a window into the child’s thinking and find clues as to what they are capable of.

An observation is often prompted by a question. Here are a few questions that might guide your next observation:

- “In what ways are the children using the new materials in the block area?”

- “Which children can cut a zig-zag line with scissors?”

- “Who will recognize their name tag that is posted on the outside table?”

- “Will Sofia play with a peer today or keep to herself?”

- “I wonder how Jackson will do at drop-off today?”

- “I’m curious to see how the children will react to painting with fall leaves and who will try?

- “What activity area are the children using the most while outside?”

As teachers observe to find answers to questions like those mentioned above, they will need to record what children are doing and saying. No matter which tool, technique or method is used, teachers need to document what they are observing.

Step 2: Documentation – Recording Evidence and Gathering Artifacts

Documentation provides the vital evidence and visual artifacts that teachers need to accurately track each child’s learning, growth and development in order to plan developmentally appropriate curriculum. Documentation helps teachers hold into memory the significant moments of play, exploration and learning. To gather data, teachers can opt to use several tools and techniques. Whether a teacher uses an anecdotal note, frequency count, or checklist to gather documentation, the goal is to have an extensive collection of factual evidence, along with work samples, that highlight each child’s actions and behaviors, verbal and nonverbal communication skills, social interaction and intellectual abilities.

Let’s take a moment to reiterate information that was discussed in a previous chapter about how to write effective evidence. First, all documentation needs to be factual. Teachers need to write down exactly what the children do and say. Second, it is suggested that you record as many descriptive details as you can, while remaining as objective as possible. Third, document the whole child’s development. More specifically,

- Look for what children “can do” and note the milestones that have been mastered

- Track language development by recording pertinent conversations

- Track play patterns to see who engages in cooperative play and who prefers to play alone

- Watch the interactions and social dynamics between peers

- Next, in order to track a child’s development over time, remember to include the following information: date; time; location and

setting; activity; and note the children that are engaged in the activity. Lastly, to plan meaningful curriculum, you will need to

regularly review all the documentation you have collected so that you can ponder and interpret what was observed.

Pin It! Documentation Sample

Date: 2/10/19

Time: 9:30 -9:45

Location and Setting: Inside during Active Investigation Time. The following centers were open: Science – magnifying glass

and leaves, Art – painting with pom poms, blocks with transportation vehicles, computer station – Clifford the Big Red Dog.

Activity : Science Area

Children Present: Hannah and Zoey

Hannah and Zoey were in the science area. They scooted their chairs up to the counter where the class pet gecko was perched.

“Hello, Gex. How are you today? What are you eating? Asked Hannah. I love Gexy Gex don’t you? Zoey asked Hannah.

“Yeaaah,” said Hannah. “I wish I had Gex,” said Zoey. “Me too!” Said Hannah. The 2 girls sat next to Gex the Gecko until it

was clean up time (about 10 minutes). Hannah sat with her back to Zoey. Zoey played with Hannah’s hair (brushing it with her

fingers maybe braiding it or putting it in a ponytail). They continued to chat back and forth to each other.

What are you able to interpret from this interaction?

You can learn more about documentation in this video by First 5 California “For the Record: Documenting Young Children’s

Learning and Development” : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-WAy474XE6s

Video is private on YouTube

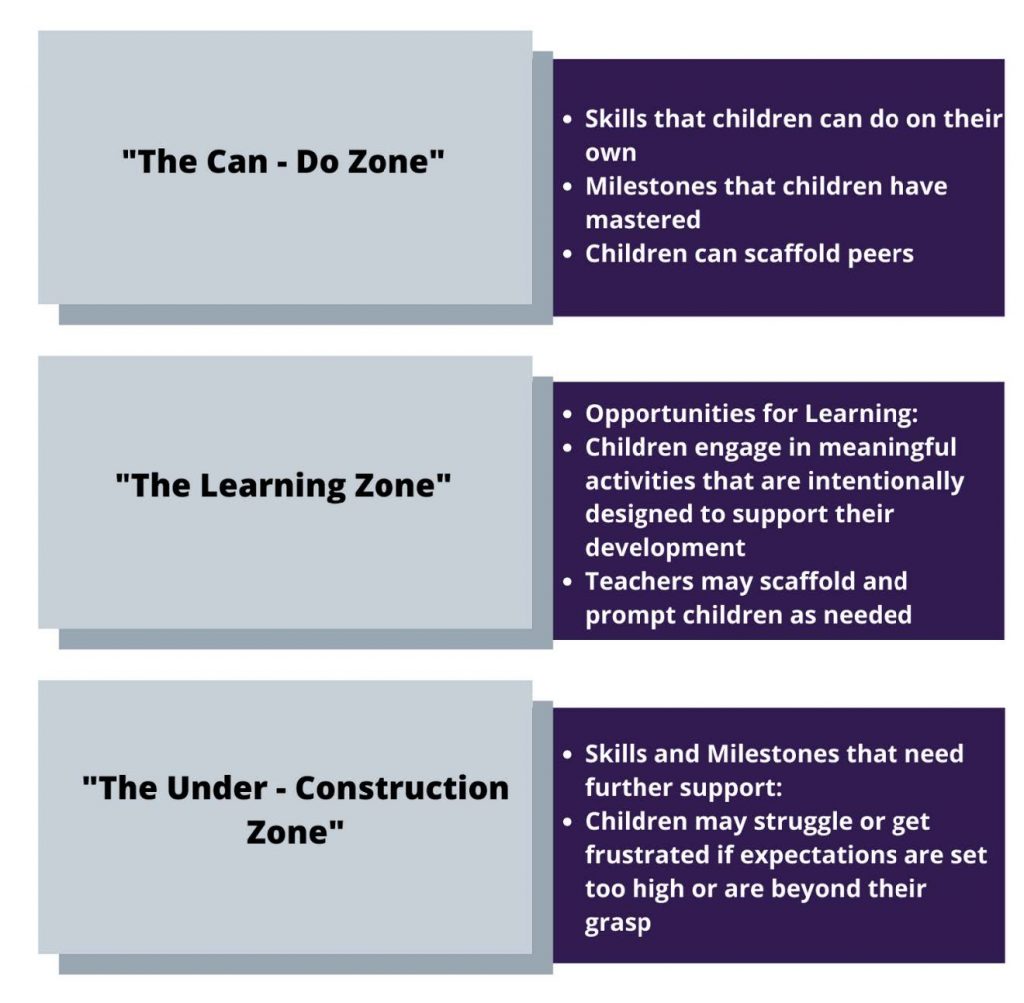

Step 3: Interpretation – Analyzing Observation Data

Before a teacher can reflect and plan developmentally appropriate curriculum, they must first interpret and analyze the documentation they have gathered. Ideally, as you observe and document, you are in the moment gathering snippets of detailed information and writing down objective facts. Once you have collected your data, only then will you begin to analyze “what does this all mean?”. As you review your documentation, you begin to think about each child’s individual actions, mannerisms, and behaviors, as well as ponder over peer interactions and group dynamics. Planning developmentally appropriate curriculum is somewhat like putting a puzzle together. As you wonder about the “why, who, what, when and how” you begin to put the pieces in place and generate potential curriculum ideas. First, you think about what the child can do on their own, and the milestones they have already mastered. Next, you think about if you are meeting each child where they are at developmentally. Then, you look for the areas of development that need further support. Lastly, you think about the zone of proximal development and how you might scaffold the children’s learning so they can reach their potential learning goals. Ultimately, your interpretations will guide your planning efforts. Let’s review the chart below[2]: The three zones of proximal development.

Besides analyzing documentation on your own, you can share information with your co-teachers. With factual notes and work samples that document what a child does or says, teachers can collectively discuss what they think, and they can pose additional questions. For example, at some programs, one teacher works a morning shift and a co-teacher works in the afternoon. Although they each will have their own set of observations, having the opportunity to collaborate and share information about the children in their care will only enhance their effectiveness when planning curriculum. Here are some possible questions they can ask each other:

- “What growth do you see?”

- “Are the peer interactions the same in the afternoon as they are in the morning?”

- “What are your thoughts on this behavior?”

- “How did you handle this transition?”

The high-quality practice of collaborating with co-teachers provides both professional and ethical support. When co-teachers are able to meet and discuss their observations, not only are they able to share their successes, they can also share their struggles. A coteacher who is working alongside you will be familiar with the children and may have valuable insight that will help with your curriculum planning. They may be able to offer suggestions from a different perspective, as well as provide encouragement and empathy as needed. Another benefit of collaborating with a co-teacher is having the opportunity to share resources and materials with each other. Shared resources can extend curriculum possibilities.[3]

Whether you analyze your data on your own or collectively with a co-teacher, it is the careful interpretation of observations and documentation that generates ideas for the next steps in planning curriculum. [footnoteThe Integrated Nature of Learning. (2016) California Department of Education. Retrieved from https://www.cde.ca.gov/sp/cd/re/documents/intnatureoflearning2016.pdf[/footnote]

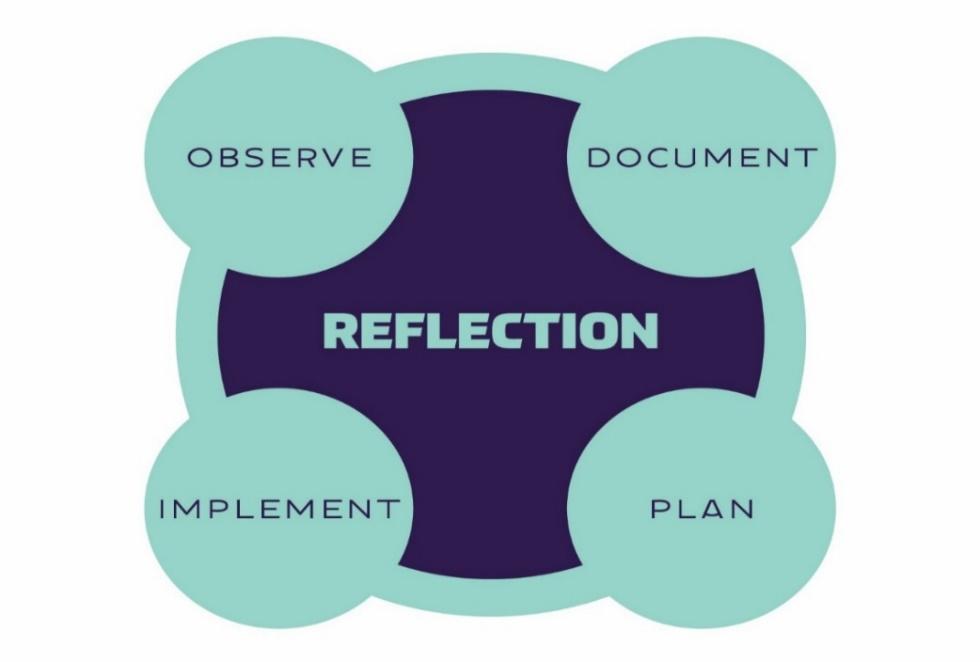

Step 4 Reflection: Planning for the Next Step

It is during the reflective process that interpreting the meaning of children’s behaviors and interactions becomes important. These interpretations give us insight into each child’s story. Each child’s story informs our responsive practice. With this valuable insight, we can:

- Adapt the environment

- Modify the daily schedule and/or routines

- Make decisions about how to guide the children’s learning based on what the child knows and can do as well as what the child is ready to try. [4]

Curriculum planning requires a considerable amount of time. Teachers need time to observe and collect documentation, they need time to interpret their data, and they need time to reflect on how to use that data to plan effective strategies that will foster a child’s learning. High-quality preschool programs that support intentional teaching allocate time in teachers’ schedules for them to reflect and plan curriculum individually and collectively as a team.[5]

As we reflect, we must ask ourselves a wide range of questions. The answers to these questions lead to individualized care and learning. Let’s look at a few questions you may ask yourself as you begin to plan developmentally appropriate curriculum:

- What skill or activity does the child appear to be working on?

- What learning strategies is the child using to play with different toys?

- Does the child engage with objects or people differently than a month ago? What has changed? What has not changed?

- Do my actions affect the outcomes of the child’s experience? How so?

- How does the information relate to goals for the child? The family’s goals? The program’s school readiness goals?

Once we have reviewed all our data we can plan meaningful curriculum. The most effective curriculum will:

- Motivate children to explore their environment

- Inspire children to investigate various centers and activities

- Encourage children to create with new materials

- Allow children to engage in conversations and prompt them to ask questions

- Prompt children to interact with peers

- Permit children to problem solve

- Celebrate diversity and embrace uniqueness

- Accommodate each child’s learning styles and individual needs

As teachers reflect on children’s play, they discover possibilities for designing curriculum to sustain, extend, and help children’s play to be more complex and, consequently, support the children’s continual learning. Teachers review ideas for possible next steps in the curriculum. Possible steps might include adding materials to interest areas, books to read with large or small groups, activities to do in small groups, or a topic to investigate over time with the children. With clear ideas or objectives in mind, teachers plan curriculum that includes strategies to enhance the learning of all children in a group, as well as strategies to support the learning of individual children.

Pin It! Observation and Documentation

Date: 10/10/19

Time : 10:45 – 10:55 am

Location and Setting : Inside during open exploration the following centers were open – easel painting, blocks with fall materials, dramatic play with firefighter and homelife, math center with pumpkin cut outs for counting

Activity: Dramatic Play Area and Library Area

Children Present : Joey

Joey played in the dramatic play area. He was dressed up in the firefighter outfit. He held the toilet paper roll in his left hand and pointed it towards a basket of stuffed animals. As he waived the toilet paper roll back and forth (side to side) he said “psssshhhhhsssshhh.” After a minute or so, Joey dropped the toilet paper roll and picked up a stuffed doggie from the basket. He took the stuffed animal to the table. As he pet the doggie, he said “You’re ok, You’re ok aren’t ya.” He then kissed the doggie on the nose, picked it up and carried it over to the library area where he sat down on the carpet square. He put the dog in his lap and started to look through a book.

Interpretation:

- With the recent fires, I wonder if Joey saw firefighters on the news or working in his neighborhood?

- I wonder if Joey has family members that are firefighters?

- I wonder what other community helpers would be interesting to explore?

- Joey has not been observed reading before, I’m curious to see what milestones he has mastered? Can he turn the pages?

- Can he recognize letters or words? Can he recall information?

- Joey played by himself. In previous observations he played with Martin. I wonder if they had a disagreement with Martine.

- I wonder if Joey needed time to himself. Maybe Martin wasn’t interested in playing firefighters.

Reflection:

- What materials can I add to the dramatic play area to extend Joey’s interest in pretending to be a firefighter?

- Are there storybooks about community helpers that highlight firefighters?

Step 5: Implementation

Once a plan has been formally written, teachers will implement it accordingly. While implementing the plan, teachers watch and listen to determine if the curriculum was effective. They will watch how children respond to the activities, materials and resources, and how they interact with peers and the environment, and how they process new information. In essence, teachers are looking for “the light bulb to go off.” It is during the implementation step that the curriculum planning cycle begins again.

Think About It…Consider this Case Study

For the past few weeks, children in Miss Emily’s class (ages 3-5 years) have been watching the crops across the preschool grow. During lunchtime, Miss Emily heard the children talking about what they had for lunch. Later in the day, the children watched the sprinklers water the yard and ask the teacher about how the water gets to the sprinklers to water the grass. While playing outside at the sensory table, four children are fascinated with pouring and dumping water into pipes and seeing how far it can travel.

Observation: Lucas is somewhat cautious in joining others in play. He stands to the side and watches others as they play.

Interpretation: Lucas appears to want to join the play, but may need just a little bit of support. I plan to watch for moments when he is on the sidelines of play, and find ways to invite him into the social play, and stay with him to support him in his encounters with the other children.

Questions to Consider

What can you infer about the children’s interests?

What can you infer about their knowledge base?

It would be safe to say that these children understand that for plants to grow, you need to water them. It would also be safe to infer that the children are most likely interested in how water travels, as you observed their actions at the water table and their questions of where and how water gets to sprinkler systems. As an intentional teacher, with your observations, you would maybe consider doing your next unit on water systems where you can incorporate all developmental domains, based on the children’s interests

- California Department of Education. (2000). Ages and Stages of Development - Child Development (CA Dept of Education). https://www.cde.ca.gov/sp/cd/re/caqdevelopment.asp ↵

- The Integrated Nature of Learning. (2016) California Department of Education. Retrieved from https://www.cde.ca.gov/sp/cd/re/documents/intnatureoflearning2016.pdf ↵

- Davis, L. (2019). Teacher Collaboration: How to Approach it in 2019. https://www.schoology.com/blog/teacher-collaboration ↵

- Observation: The Heart of Individualizing Responsive Care. (2013) Office of Head Start. Retrieved from https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/ehs-ta-paper-15-observation.pdf ↵

- California Preschool Curriculum Framework, Volume 1 (2010). California Department of Education. Retrieved from https://www.cde.ca.gov/sp/cd/re/documents/psframeworkkvol1.pdf ↵