2.1 Current Issues

Learning Objectives

- Identify current issues that impact stakeholders in early childhood care and education.

- Describe strategies for understanding current issues as a professional in early childhood care and education.

- Create an informed response to a current issue as a professional in early childhood care and education.

Current Issues in the Field

There’s one thing you can be sure of in the field of early childhood: the fact that the field is always changing. We make plans for our classrooms based on the reality we and the children in our care are living in, and then, something happens in that external world, the place where “life happens,” and our reality changes. Or sometimes it’s a slow shift: you go to a training and hear about new research, you think it over, read a few articles, and over time you realize the activities you carefully planned are no longer truly relevant to the lives children are living today, or that you know new things that make you rethink whether your practice is really meeting the needs of every child.

This is guaranteed to happen at some point. Natural events might occur that affect your community, like forest fires or tornadoes, or like COVID-19, which closed far too many child care programs and left many other early educators struggling to figure out how to work with children online. Cultural and political changes happen, which affect your children’s lives, or perhaps your understanding of their lives, like the Black Lives Matter demonstrations that brought to light how much disparity and tension exist and persist in the United States. New information may come to light through research that allows us to understand human development very differently, like the advancements in neuroscience that help us understand how trauma affects children’s brains, and how we as early educators can counteract those affects and build resilience.

And guess what—all this change is a good thing! Read this paragraph slowly—it’s important! Change is good because we as providers of early childhood care and education are working with much more than a set of academic skills that need to be imparted to children; we are working with the whole child, and preparing the child to live successfully in the world. So when history sticks its foot into our nice calm stream of practice, the waters get muddied. But the good news is that mud acts as a fertilizer so that we as educators and leaders in the field have the chance to learn and grow, to bloom into better educators for every child, and, let’s face it, to become better human beings!

You may know at an intellectual level that change is part of the deal, but what about deep down? Do you sometimes long for everything to just stay the same for a little while (especially when on vacation)? When you consider the idea of change, how does it make you feel? Anxious? Excited? Maybe just a little tired? What factors impact your response? What were your first thoughts when you sat back and FELT the reality of ever present change?

You may know at an intellectual level that change is part of the deal, but what about deep down? Do you sometimes long for everything to just stay the same for a little while (especially when on vacation)? When you consider the idea of change, how does it make you feel? Anxious? Excited? Maybe just a little tired? What factors impact your response? What were your first thoughts when you sat back and FELT the reality of ever present change?

The work of early childhood care and education is so full, so complex, so packed with details to track and respond to, from where Caiden left his socks, to whether Amelia’s parents are going to be receptive to considering evaluation for speech supports, and how to adapt the curriculum for the child who has never yet come to circle time. It might make you feel a little uneasy—or, let’s face it, even overwhelmed—to also consider how the course of history may cause you to deeply rethink what you do over time.

That’s normal. Thinking about the complexity of human history while pushing Keisha on the swings makes you completely normal! As leaders in the field, we must learn to expect that we will be called upon to change, maybe even dramatically, over time.

Now, put your educator hat on. Can you think of a time in your own education when something occurred that your teachers had to adapt to? Maybe a natural event, or a political or cultural one? What did they do to adapt to the event? Or maybe they didn’t adapt—what happened then? What can you learn from this memory?

Now, put your educator hat on. Can you think of a time in your own education when something occurred that your teachers had to adapt to? Maybe a natural event, or a political or cultural one? What did they do to adapt to the event? Or maybe they didn’t adapt—what happened then? What can you learn from this memory?

Let me share a personal story with you: I had just become director of an established small center, and was working to sort out all the details that directing encompassed: scheduling, billing policies, and most of all, staffing frustrations about who got planning time, etc. But I was also called upon to substitute teach on an almost daily basis, so there was a lot of disruption to my carefully made daily plans to address the business end, or to work with teachers to seek collaborative solutions to long-standing conflict. I was frustrated by not having time to do the work I felt I needed to do, and felt there were new small crises each day. I couldn’t get comfortable with my new position, nor with the way my days were constantly shifting away from my plans. It was then that a co-worker shared a quote with me from Thomas F. Crum, who writes about how to thrive in difficult working conditions: “Instead of seeing the rug being pulled from under us, we can learn to dance on a shifting carpet”.[1]

Wow! That gave me a new vision, one where I wasn’t failing and flailing, but could become graceful in learning to be responsive to change big and small. I felt relieved to have a different way of looking at my progress through my days: I wasn’t flailing at all—I was dancing! Okay, it might be a clumsy dance, and I might bruise my knees, but that idea helped me respond to each day’s needs with courage and hope.

I especially like this image for those of us who work with young children. I imagine a child hopping around in the middle of a parachute, while the other children joyfully whip their corners up and down. The child in the center feels disoriented, exhilarated, surrounded by shifting color, sensation, and laughter. When I feel like there’s too much change happening, I try to see the world through that child’s eyes. It’s possible to find joy and possibility in the disorientation, and the swirl of thoughts and feelings, and new ways of seeing and being that come from change.

You are a leader, and change is happening, and you are making decisions about how to move forward, and how to adapt thoughtfully. The good news is that when this change happens, our field has really amazing tools for adapting. We can develop a toolkit of trusted sources that we can turn to to provide us with information and strategies for ethical decision making.

Key Takeaways

- Our practices in the classroom and as leaders must constantly adapt to changes in our communities and our understanding of the world around us, which gives us the opportunity to continue to grow and develop.

If You’re Afraid of Falling…

One of the most important of these is the NAEYC Code of Ethical Conduct, which expresses a commitment to core values for the field, and a set of principles for determining ethical behavior and decision-making. As we commit to the code, we commit to:

- Appreciate childhood as a unique and valuable stage of the human life cycle

- Base our work on knowledge of how children develop and learn

- Appreciate and support the bond between the child and family

- Recognize that children are best understood and supported in the context of family, culture,* community, and society

- Respect the dignity, worth, and uniqueness of each individual (child, family member, and colleague)

- Respect diversity in children, families, and colleagues

- Recognize that children and adults achieve their full potential in the context of relationships that are based on trust and respect.

If someone asked us to make a list of beliefs we have about children and families, we might not have been able to come up with a list that looked just like this, but, most of us in the field are here because we share these values and show up every day with them in our hearts.

The Code of Ethical Conduct can help bring what’s in your heart into your head. It’s a complete tool to help you think carefully about a dilemma, a decision, or a plan, based on these values. Sometimes we don’t make the “right” decision and need to change our minds, but as long as we make a decision based on values about the importance of the well-being of all children and families, we won’t be making a decision that we will regret.

Can you think of a time that you had to make a really hard decision and you were able to base that decision in a deeply held value like “family is the most important thing” or “my education comes first?” How did basing your decision in personal or professional values help you to make a decision? Are you experiencing change in some aspect of your life right now that you can link to a personal or professional value to help you move forward? As you reflect on whatever the hard change might be, are you able to explain your choices from a values standpoint? For example, maybe you are deciding whether to go to school full time next term or go only part time to be more present with your family. Which values would you lean on to help you decide to go full time? Which values would you lean on to decide to go part time? Neither is wrong—but deciding which values are most important to you at the time can help you make your decision.

Can you think of a time that you had to make a really hard decision and you were able to base that decision in a deeply held value like “family is the most important thing” or “my education comes first?” How did basing your decision in personal or professional values help you to make a decision? Are you experiencing change in some aspect of your life right now that you can link to a personal or professional value to help you move forward? As you reflect on whatever the hard change might be, are you able to explain your choices from a values standpoint? For example, maybe you are deciding whether to go to school full time next term or go only part time to be more present with your family. Which values would you lean on to help you decide to go full time? Which values would you lean on to decide to go part time? Neither is wrong—but deciding which values are most important to you at the time can help you make your decision.

An Awfully Big Current Issue—Let’s Not Dance Around It

You might be wondering how we link the Code of Ethical Conduct to the change all around us—let’s roll up our sleeves and dive into an example that has risen to the forefront in our culture and in early childhood care and education in recent years: skin color, bias, and prejudice. We hear the terms “race and racism” used to identify these issues in media and news. Tensions within and toward communities and individuals of color have been especially visible in the news because of the heightened impact of COVID-19 on communities of color, the highly visible police violence against black and brown men and women, and the subsequent demonstrations that took place in 2020. Children see and hear the media and adult conversations, and they feel the unease, or even fear, around questions of difference. This has heightened our responsibility as early educators to approach these issues in the classroom, and to do it with sensitivity and self-awareness.

In the field of early childhood, issues of prejudice have long been important to research, and in this country, Head Start was developed more than 50 years ago with an eye toward dismantling disparity based on ethnicity or skin color (among other things). However, research shows that this gap has not closed. Particularly striking, in recent years, is research addressing perceptions of the behavior of children of color and the numbers of children who are asked to leave programs.

In fact, studies of expulsion from preschool showed that black children were twice as likely to be expelled as white preschoolers, and 3.6 times as likely to receive one or more suspensions.[2]This is deeply concerning in and of itself, but the fact that preschool expulsion is predictive of later difficulties is even more so:

Starting as young as infancy and toddlerhood, children of color are at highest risk for being expelled from early childhood care and education programs. Early expulsions and suspensions lead to greater gaps in access to resources for young children and thus create increasing gaps in later achievement and well-being… Research indicates that early expulsions and suspensions predict later expulsions and suspensions, academic failure, school dropout, and an increased likelihood of later incarceration.

Why does this happen? It’s complicated. Studies on the K-12 system show that some of the reasons include:

- uneven or biased implementation of disciplinary policies

- discriminatory discipline practices

- school racial climate

- under resourced programs

- inadequate education and training for teachers on bias

In other words, educators need more support and help in reflecting on their own practices, but there are also policies and systems in place that contribute to unfair treatment of some groups of children.

So…we have a lot of research that continues to be eye opening and cause us to rethink our practices over time, plus a cultural event—in the form of the Black Lives Matter movement—that push the issue of disparity based on skin color directly in front of us. We are called to respond. You are called to respond.

Key Takeaways

It is not possible to simultaneously “respect the dignity, worth, and uniqueness of every individual” and watch a significant number of students from a particular group be expelled from their early learning experience, realizing this may frequently be a first step in a process of punishment by loss of opportunity.

How Will I Ever Learn the Steps?

Woah—how do I respond to something so big and so complex and so sensitive to so many different groups of people?

As someone drawn to early childhood care and education, you probably bring certain gifts and abilities to this work.

- You probably already feel compassion for every child and want every child to have opportunities to grow into happy, responsible adults who achieve their goals. Remember the statement above about respecting the dignity and worth of every individual? That in itself is a huge start to becoming a leader working as an advocate for social justice.

- You may have been to trainings that focus on anti-bias and being culturally responsive.

- You may have some great activities to promote respect for diversity, and be actively looking for more.

- You may be very intentional about including materials that reflect people with different racial identities, genders, family structures.

- You may make sure that each family is supported in their home language and that multilingualism is valued in your program.

- You may even have spent some time diving into your own internalized biases.

This list could become very long! These are extremely important aspects of addressing injustice in early education which you can do to alter your individual practice with children.

As a leader in the field, you are called to think beyond your own practice. As a leader you have the opportunity—the responsibility!—to look beyond your own practices and become an advocate for change. Two important recommendations (of many) from the NAEYC Advancing Equity in Early Childhood Education Position Statement, another important tool:

Speak out against unfair policies or practices and challenge biased perspectives. Work to embed fair and equitable approaches in all aspects of early childhood program delivery, including standards, assessments, curriculum, and personnel practices.

Look for ways to work collectively with others who are committed to equity. Consider it a professional responsibility to help challenge and change policies, laws, systems, and institutional practices that keep social inequities in place.

One take away I want you to grab from those last sentences: You are not alone. This work can be, and must be, collective.

As a leader, your sphere of influence is bigger than just you. You can influence the practices of others in your program and outside of it. You can influence policies, rules, choices about the tools you use, and ultimately, you can even challenge laws that are not fair to every child.

Who’s on your team? I want you to think for a moment about the people who help you in times where you are facing change. These are the people you can turn to for an honest conversation, where you can show your confusion and fear, and they will be supportive and think alongside you. This might include your friends, your partner, some or all of your coworkers, a former teacher of your own, a counselor, a pastor. Make a quick list of people you can turn to when you need to do some deep digging and ground yourself in your values.

And now, your workplace team: who are your fellow advocates in your workplace? Who can you reach out to when you realize something might need to change within your program?

Wonderful. You’ve got other people to lean on in times of change. More can be accomplished together than alone. Let’s consider what you can do:

What is your sphere of influence? What are some small ways you can create room for growth within your sphere of influence? What about that workplace team? Do their spheres of influence add to your own?

Try drawing your sphere of influence: Draw yourself in the middle of the page, and put another circle around yourself, another circle around that, and another around that. Fill your circles in:

- Consider the first circle your personal sphere. Brainstorm family and friends who you can talk to about issues that are part of your professional life. You can put down their names, draw them, or otherwise indicate who they might be!

- Next, those you influence in your daily work, such as the children in your care, their families, maybe your co-workers land here.

- Next, those who make decisions about the system you are in—maybe this is your director or board, or even a PTA.

- Next, think about the early childhood care and education community you work within. What kind of influence could you have on this community? Do you have friends who work at other programs you can have important conversations with to spread ideas? Are you part of a local Association for the Education of Young Children (AEYC)? Could you speak to the organizers of a local conference about including certain topics for sessions?

- And finally, how about state (and even national) policies? Check out The Children’s Institute to learn about state bills that impact childcare. Do you know your local representatives? Could you write a letter to your senator? Maybe you have been frustrated with the slow reimbursement and low rates for Employment Related Day Care subsidies and can find a place to share your story. You can call your local Child Care Resource and Referral, your local or state AEYC chapter, or visit childinst.org to find out how you can increase your reach! It’s probably a lot farther than you think!

Break It Down: Systemic Racism

When you think about injustice and the kind of change you want to make, there’s an important distinction to understand in the ways injustice happens in education (or anywhere else). First, there’s personal bias and racism, and of course it’s crucial as an educator to examine ourselves and our practices and responses. We all have bias and addressing it is an act of courage that you can model for your colleagues.

In addition, there’s another kind of bias and racism, and it doesn’t live inside of individual people, but inside of the systems we have built. Systemic racism exists in the structures and processes that have come into place over time, which allow one group of people a greater chance of succeeding than other specific groups of people.

Key Takeaway

Systemic racism is also called institutional racism, because it exists – sometimes unquestioned – within institutions themselves.

In early childhood care and education, there are many elements that were built with middle class white children in mind. Many of our standardized tests were made with middle class white children in mind. The curriculum we use, the assessments we use, the standards of behavior we have been taught; they may have all been developed with middle class white children in mind.

Therefore it is important to consider whether they adequately and fairly work for all of the children in your program community. Do they have relevance to all children’s lived experience, development, and abilities? Who is being left out?

Imagine a vocabulary assessment in which children are shown common household items including a lawn mower…common if you live in a house; they might well be unfamiliar to a three-year-old who lives in an apartment building, however. The child may end up receiving a lower score, though their vocabulary could be rich, full of words that do reflect the objects in their lived experience.

The test is at fault, not the child’s experience. Yet the results of that test can impact the way educators, parents, and the child see their ability and likelihood to succeed.

Key Takeaways

Leaders in early childhood care and education have an ethical obligation to value every child’s unique experiences, family, and community. In order to make sure your program values every child, you must make choices that ensure that each child, especially those who are part of groups that have not had as many resources, receive what they need in order to reach outcomes.

You Don’t Have to Invent the Steps: Using an Equity Lens

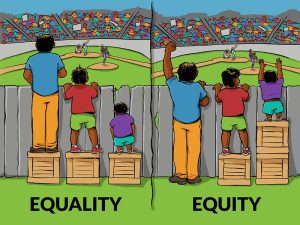

In addition to the NAEYC Code of Ethical Conduct and Equity Statement, another tool for addressing decision-making is an equity lens. To explain what an equity lens is, we first need to talk about equity. It’s a term you may have heard before, but sometimes people confuse it with equality. It’s a little different – equity is having the resources needed to be successful.

There’s a wonderful graphic of children looking over a fence at a baseball game. In one frame, each child stands at the fence; one is tall enough to see over the top; another stands tip-toe, straining to see; and another is simply too short. This is equality—everyone has the same chance, but not everyone is equally prepared. In the frame titled equity, each child stands on a stool just high enough so that they may all see over the fence. The stools are the supports they need to have an equitable outcome—being able to experience the same thing as their friend.

Seeking equity means considering who might not be able to see over the fence and figuring out how to build them a stool so that they have the same opportunity.

An equity lens, then, is a tool to help you look at decisions through a framework of equity. It’s a series of questions to ask yourself when making decisions. An equity lens is a process of asking a series of questions to better help you understand if something (a project, a curriculum, a parent meeting, a set of behavioral guidelines) is unfair to specific individuals or groups whose needs have been overlooked in the past. This lens might help you to identify the impact of your decisions on students of color, and you can also use the lens to consider the impact on students experiencing poverty, students in nontraditional families, students with differing abilities, students who are geographically isolated, students whose home language is other than English, etc.) The lens then helps you determine how to move past this unfairness by overcoming barriers and providing equitable opportunities to all children.

Some states have adopted a version of the equity lens for use in their early learning systems. Questions that are part of an equity lens[3] might include:

- What decision is being made, and what kind of values or assumptions are affecting how we make the decision?

- Who is helping make the decision? Are there representatives of the affected group who get to have a voice in the process?

- Does the new activity, rule, etc. have the potential to make disparities worse? For instance, could it mean that families who don’t have a car miss out on a family night? Or will it make those disparities better?

- Who might be left out? How can we make sure they are included?

- Are there any potential unforeseen consequences of the decision that will impact specific groups? How can we try to make sure the impact will be positive?

You can use this lens for all kinds of decisions, in formal settings, like staff meetings, and you can also work to make them part of your everyday thinking. I have a sticky note on my desk that asks “Who am I leaving out”? This is an especially important question if the answer points to children who are people of color, or another group that is historically disadvantaged. If that’s the answer, you don’t have to scrap your idea entirely. Celebrate your awareness, and brainstorm about how you can do better for everyone—and then do it!

Key Takeaways

Racism and other forms of injustice can be built into the systems we work within—even if each individual is working hard not to recognize and root out their individual biases. As a leader, you can do work that will impact the system and undo these unjust practices or structures!

Embracing our Bruised Knees: Accepting Discomfort as We Grow

Inspirational author Brene Brown, who writes books, among other things, about being an ethical leader, said something that really walloped me: if we avoid the hard work of addressing unfairness (like talking about skin color at a time when our country is divided over it) we are prioritizing our discomfort over the pain of others.[4]

Imagine a parent who doesn’t think it’s appropriate to talk about skin color with young children, who tells you so with some anger in their voice. That’s uncomfortable, maybe even a little scary. But as you prioritize upholding the dignity, worth, and uniqueness of every individual, you can see that this is more important than trying to avoid discomfort. Changing your practice to avoid conflict with this parent means prioritizing your own momentary discomfort over the pain children of color in your program may experience over time.

We might feel vulnerable when we think about skin color, and we don’t want to have to have the difficult conversation. But if keeping ourselves safe from discomfort means that we might not be keeping children safe from very real and life-impacting racial disparity, we’re not making a choice that is based in our values.

Can you think of a time that you prioritized your comfort over someone else’s pain? I can! I’ve avoided uncomfortable conversations about disparity lots of times, for instance (though I also try really hard to be courageous and open when faced with these moments, and think I am doing better). Once you’ve thought of your example, take yourself back to the moment when you were deciding what to do, and say to yourself: I will not prioritize my own discomfort over the pain of others! Now grant yourself a do-over. Imagine what you would have done instead. How does it feel? Is the discomfort manageable? Does it go away? What other feelings do you experience?

Can you think of a time that you prioritized your comfort over someone else’s pain? I can! I’ve avoided uncomfortable conversations about disparity lots of times, for instance (though I also try really hard to be courageous and open when faced with these moments, and think I am doing better). Once you’ve thought of your example, take yourself back to the moment when you were deciding what to do, and say to yourself: I will not prioritize my own discomfort over the pain of others! Now grant yourself a do-over. Imagine what you would have done instead. How does it feel? Is the discomfort manageable? Does it go away? What other feelings do you experience?

Change is uncomfortable. It leaves us feeling vulnerable as we reexamine the ideas, strategies, even the deeply held beliefs that have served us so far. But as a leader, and with the call to support every child as they deserve, we can develop a sort of super power vision, where we can look unflinchingly around us and understand the hidden impacts of the structures we work within.

A Few Recent Dance Steps of My Own

You’re definitely not alone—researchers and thinkers in the field are doing this work alongside you, examining even our most cherished and important ideas about childhood and early education. For instance, a key phrase that we often use to underpin our decisions is developmentally appropriate practice, which NAEYC defines as “methods that promote each child’s optimal development and learning through a strengths-based, play-based approach to joyful, engaged learning.” The phrase is sometimes used to contrast against practices that might not be developmentally appropriate, like expecting three-year-olds to write their names or sit quietly in a 30 minute story time.

But we have to consider how we as a field have determined what is developmentally appropriate. We do have science to build on, a strong understanding of brain development and its impact on regulation, impulse control, language acquisition, etc. But we also have a set of cultural values that impact what we believe to be appropriate.

But we have to consider how we as a field have determined what is developmentally appropriate. We do have science to build on, a strong understanding of brain development and its impact on regulation, impulse control, language acquisition, etc. But we also have a set of cultural values that impact what we believe to be appropriate.

Let me tell you a story about how professional development is still causing me to stare change in the face! At the NAEYC conference in 2020, during a session in which Dr. Jie-Qi Chen presented on different perspectives on developmentally appropriate practice among early educators in China and the United States. She showed a video from a classroom in China to educators in both the US and in China. The video was of a circle time in which a child was retelling a story that the class knew well, and then the children were encouraged to offer feedback and rate how well the child had done. The children listened attentively, and then told the storytelling child how they had felt about his retelling, including identifying parts that had been left out, inaccuracies in the telling, and advice for speaking more clearly and loudly.

The educators were asked what the impact of the activity would be on the children and whether it was developmentally appropriate. The educators in the United States had deep concerns that the activity would be damaging to a child’s self esteem, and was therefore not developmentally appropriate. They also expressed concerns about the children being asked to sit for this amount of time. The educators in the classroom in China felt that it was developmentally appropriate and the children were learning not only storytelling skills but how to give and receive constructive criticism.

As I watched the video, I had the same thoughts as the educators from the US—I’m not used to children being encouraged to offer criticism rather than praise. But I also saw that the child in question had self-confidence and received the feedback positively. The children were very engaged and seemed to feel their feedback mattered.

What was most interesting to me here was the idea of self-esteem, and how important it is to us here in the United States, or rather, how much protecting we feel it needs. I realized that what educators were responding to weren’t questions of whether retelling a story was developmentally appropriate, or whether the critical thinking skills the children were being asked to display were developmentally appropriate, but rather whether the social scenario in which one child receives potentially negative feedback in front of their peers was developmentally appropriate, and that the responses were based in the different cultural ideas of self-esteem and individual vision versus collective success.

My point here is that even our big ideas, like developmentally appropriate practice, have an element of vulnerability to them. As courageous leaders, we need to turn our eyes even there to make sure that our cultural assumptions and biases aren’t affecting our ability to see clearly, that the reality of every child is honored within them, and that no one is being left out. And that’s okay. It doesn’t mean we should scrap them. It’s not wrong to advocate for and use developmentally appropriate practice as a framework for our work—not at all! It just means we need to remember that it’s built from values that may be specific to our culture—and not everyone may have equal access to that culture. It means we should return to our big ideas with respect and bravery and sit with them and make sure they are still the ones that serve us best in the world we are living in right now, with the best knowledge we have right now.

Key Takeaway

Even our big ideas, the really important ones that underlie our philosophies, can’t be assumed to be a universal truth, because they are affected by our beliefs and values. As leaders, we are called upon to be extra courageous and extra thoughtful in examining these beliefs and making sure they are a firm ground for every unique child to stand on.

You, Dancing With Courage

So…As a leader is early childhood, you will be called upon to be nimble, to make new decisions and reframe your practice when current events or new understanding disrupt your plans. When this happens, professional tools are available to you to help you make choices based on your ethical commitment to children.

Change makes us feel uncomfortable but we can embrace it to do the best by the children and families we work with. We can learn to develop our critical thinking skills so that we can examine our own beliefs and assumptions, both as individuals and as a leader.

Remember that person dancing on the shifting carpet? That child in the middle of the parachute? They might be a little dizzy, but with possibility. They might lose their footing, but in that uncertainty, in the middle of the billowing parachute, there is the sensation that the very instability provides the possibility of rising up like the fabric. And besides—there are hands to hold if they lose their balance—or if you do! And so can you rise when you allow yourself to accept change and adapt to all the new possibility of growth that it opens up!

REferences

Broughton, A., Castro, D. and Chen, J. (2020). Three International Perspectives on Culturally Embraced Pedagogical Approaches to Early Teaching and Learning. [Conference presentation]. NAEYC Annual Conference.

Adaptation Credit

Adapted from Chapter 5 in Leadership in Early Care and Education by Dr. Tammy Marino; Dr. Maidie Rosengarden; Dr. Sally Gunyon; and Taya Noland is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

- Crum, T. (1987). The Magic of Conflict: Turning a Life of Work into a Work of Art. Touchstone. ↵

- Meek, S. and Gilliam, W. (2016). Expulsion and Suspension in Early Education as Matters of Social Justice and Health Equity. Perspectives: Expert Voices in Health & Health Care. ↵

- Scott, K., Looby, A., Hipp, J. and Frost, N. (2017). “Applying an Equity Lens to the Child Care Setting.” The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics 45 (S1), 77-81. ↵

- Brown, B. (2018). Dare to lead. Vermilion. ↵