3 Evaluating Entrepreneurial Opportunities

Since idea generation and screening are relatively less costly stages in the new product development process (in terms of investment in funds, time, personnel, and escalation of commitment), it makes sense to manage the process in the most efficient and effective manner for the organization. – Rochford (1991, p. 287)

The most serious mistakes are not being made as a result of wrong answers. The truly dangerous thing is asking the wrong question. – Peter Drucker

I have no data yet. It is a capital mistake to theorize before one has data. Insensibly one begins to twist facts to suit theories, instead of theories to suit facts. – Arthur Conan Doyle

Learning Objectives

After completing this chapter you will be able to

- Apply analytical skills to assess how the nature of entrepreneurial environment can influence entrepreneurial outcomes

- Apply the right tools to analyze each of the societal, industry, market, and firm levels to evaluate entrepreneurial and other business opportunities

Overview

This chapter introduces the idea that there are different types of economies while providing examples of ways to consider how economies can differ. It also introduces the distinct levels of analyses that must be considered while stressing the importance of applying the appropriate tools to conduct the analyses at each level.

Types of Economies

When studying entrepreneurship, it is important to understand the foundations upon which the area of study stands. One way to do this is to consider perspectives on different kinds of economies. In the next sections we will consider two such perspectives. The first describes the idea of the bazaar, firm, and new economies, and the second examines the idea of the sharing economy.

Bazaar, Firm, and New Economies

Entrepreneurship has existed as long as individuals have specialized in the production of a good or service to exchange with other individuals for products they needed, but did not produce themselves. Dana, Etemad, and Wright (2008) distinguished between bazaar-type economies, firm-type economies, and the new economy.

The Bazaar-Type Economy

The Bazaar-type Economy is a social, cultural and economic system in which the physical clustering of vendors facilitates the consumer’s comparative information search, by eliminating displacement time. Business is strongly affected by relationships and networks; relationships and preferential treatment are integral to business. Consumers are not treated equally. Different people pay unlike prices. The price paid and the level of service provided is a function of status and relationships. Products and services are personalised, and this leads to customer loyalty. (Dana et al., 2008, p. 110-111)

Bazaars have been around for thousands of years and, as Dana et al. (2008) note, have several distinctive features:

- It is a way of life, a cultural and social system.

- Although it is a mode for commercial activity, relationships and alliances are the focus of the activities, not the financial transactions.

- The lowest price and the best quality are less important to purchasers because they often consider the vendor as a friend they wish to help and someone who will help them in return.

- Buyers and sellers seek to maintain long-term relationships with each other; there is little or no concern with maximizing profits.

- Vendors do not consider other vendors to be rivals and there is little interest or advantage in differentiating the products offered from those sold by others.

- Prices are established through negotiation, with buyers often making the first offer of a price. Competitive tensions are between buyers and sellers rather than between sellers.

- Once relationships are established (which reduces transaction costs), both buyers and sellers tend to have high degrees of satisfaction with the transactions.

The Firm-Type Economy

The Firm-type Economy is an economic institution in which location is a competitive advantage. In the shopping mall, for instance, an exclusivity clause protects the vendor, limiting competition. The consumer’s comparative information search involves displacement time, and an opportunity cost is involved when seeking perfect information. Business takes place primarily within a set of impersonally defined institutions. The flow of commerce is a function of strategy based on optimisation models. The purpose of transactions is to maximise wealth efficiently, and the means to this is rational and unbiased decision-making that treats buyers as equals. The price paid and the level of service provided is established by the seller. Products and services are standardised, and this leads to efficiency that in turn allows competitive pricing. (Dana et al., 2008, p. 111)

In Canada, we are more familiar with the firm-type economy. Dana et al. (2008) highlighted the following differences between it and the bazaar.

- Firm-consumer transactions are impersonal. The focus is on the interaction between the buyer and the product rather than between the buyer and seller. Product attributes are considered to be important. Relationships between buyers and sellers are trivial and secondary as compared to the transaction itself.

- Firms engage in transactions while attempting to maximize profits through rational decision-making.

- Competition is between sellers who attempt to segment the market based on types of consumers.

- Sellers generally set prices consumers are expected to accept and pay.

- The premise is that firms treat all customers equally.

The New Economy

The New Economy is a cultural and economic system in which the virtual clustering of vendors facilitates the consumer’s comparative information search, by eliminating displacement time. The flow of commerce is strongly affected by relationships and networks; relationships and preferential treatment are integral to business. Consumers are not treated equally. Different people pay unlike prices. The price paid and the level of service provided is a function of status and relationships. Products and services are customized. (Dana et al., 2008, p. 111)

Dana et al. (2008) have observed the following norms they claim are currently in place or are developing:

- Firms no longer treat all consumers equally. Some customers receive special promotional offers, preferential treatment, and other benefits over other customers.

- Differentiation is less evident than it used to be.

- The focus has shifted (back) toward establishing relationships with consumers. Different prices are charged depending upon the nature of the relationship the firm has with the customer.

- There is now less competition than before with former rivals now cooperating through networks and global alliances.

- The internet has become a medium through which transactions occur, reducing searching costs for consumers and, in some cases, inventory handling and production costs for firms. In some cases, consumers suggest the starting price in a negotiation process.

- In many ways, this new “reality is shared with the Bazaar-type Economy—a social and cultural system, a way of life and a general mode of commercial activity such that most of the flow of commerce is centred on relationships” (Dana et al., 2008, p. 115).

The Sharing Economy – Collaborative Consumption

One trend that has become more prominent of late, perhaps because new information technologies have enabled new developments in this area, involves individuals and businesses seeking new ways to share underutilized resources and develop new business models that focus on selling the use of something rather than selling the item itself. This arises from the desire to generate value from items that are not being used to their full potential by their owners: “Instead of buying and owning products, consumers are increasingly interested in leasing and sharing them. Companies can benefit from the trend toward ‘collaborative consumption’ through creative new approaches to defining and distributing their offerings” (Matzler, Veider, & Kathan, 2015).

For instance, when people have space available in their houses and wish to generate revenue from that unused or underused area, they can use Airbnb Inc. (https://www.airbnb.com/) to rent rooms. The Airbnb business model is interesting in that it facilitates the rental of spaces that it does not own. The service essentially created a new supply of accommodations for travelers in addition to the traditional hotel, motel, and bed and breakfast providers.

Uber (https://uber.com) provides people who have both a vehicle and available time with the opportunity to turn those resources into revenue by providing rides to people who need them.

Saskatoon CarShare Co-operative (http://saskatooncarshare.com/) purchases cars that its members can book online at any time. It attracts people who only need vehicles occasionally, like when they have to get groceries or run other errands:

It’s a win for you because you save money by not having to own a car.

Being a CarShare member helps you save money. A typical car-owner spends an average of $6,400 per year. That comes out to about $533 per month or $17.64/day to maintain and operate an efficient vehicle (e.g. Honda Civic). By making simple changes to integrate walking, biking, busing and CarSharing into your traveling habits you can save some serious cash. That means you can invest your money in other things, even a down payment for a home!

It is a win for the environment, the city of Saskatoon and your community.

For every CarShare vehicle out there, another five cars are taken off the road. That means fewer vehicles need to be driven, fuelled and maintained. Besides, less vehicles on the road also means less traffic on our streets. Now there’s something City Hall can get behind! (Saskatoon CarShare Co-operative, 2015)

The transaction costs—in terms of money and time—used to be very high when someone who needed something had to find a way to connect with someone else who could provide that something, and vice versa. Those transaction costs have plummeted because of the internet, and entrepreneurs are developing new methods for making unused or underused resources available to people who want them. This has formed the basis for the sharing economy.

Matzler et al. (2015) identified six ways that companies could benefit by engaging in the sharing economy:

- Sell the use of a product rather than ownership of it.

- For instance, Nova Rentals, tool and equipment rental company located in Mississauga, Ontario, rents tool and equipment for construction, landscaping, renovations, and contractors. Their customers range from large construction companies to small contractors, service businesses, and homeowners. (NOVA Rentals, 2015).

- Provide customers with the opportunity to resell products they purchased.

- Patagonia is an innovative outdoor apparel company operating under the mission to “build the best product, cause no unnecessary harm, use business to inspire and implement solutions to the environmental crisis” (Patagonia, 2015a). Although counter intuitive for many traditional business owners who strive to sell new or replacement products rather than promote less consumption, the company runs a program to “make it easy to buy, sell or trade Patagonia gear” (Patagonia, 2015b, Reuse & Recycle). They explicitly ask their customers to use the tools that Patagonia makes available to “decrease the environmental impact of their stuff over time by repairing it, finding ways to reuse it, recycling it when it’s truly ready. By buying only what they need, customers can reduce their overall consumption in the long run” (Patagonia, 2015b, para. 10). In the past, Patagonia has even partnered with companies like eBay to encourage its customers to resell used Patagonia products rather than throw them out (PR Newswire, 2011).

- By exploiting unused resources and capacities

- Airbnb essentially takes advantage of unused space to generate revenues for homeowners. An example of exploiting unused capabilities is when homeowners who generate more energy than they need through solar, wind, and other means can sell the excess back to the electricity companies.

- By providing repair and maintenance services.

- Companies like Patagonia supply repair services or make it easy for customers to repair their own apparel so that fewer new products need to be produced and less is thrown away.

- By using collaborative consumption to target new customers.

- Wolf Willow Cohousing organized in “January 2008 to explore the possibility of creating a cohousing community in Saskatoon” (Smillie, 2015, para. 1). The idea was to attract a group of like-minded older adults who would collectively develop—with the aid of project manager, architect, and construction professionals—a unique condominium housing initiative with self-contained living units and common spaces. In 2012, the 21-unit, four-level, environmentally-conscious, energy-efficient cohousing building located in a central area of Saskatoon opened with unique in-door and outdoor common areas designed specifically for the residents who were involved with designing the facility.

- The Canadian Cohousing Network (Network, 2015) provides a list of “architects, developers, facilitators, development consultants, marketers, trainers, and others” (para. 1) who can deliver services for groups wishing to develop cohousing projects.

- By developing entirely new business models enabled by collaborative consumption

- New business models, including those supporting the businesses and business types listed above, have emerged to take advantage of the current trend toward collaborative consumption.

Levels of Analyses

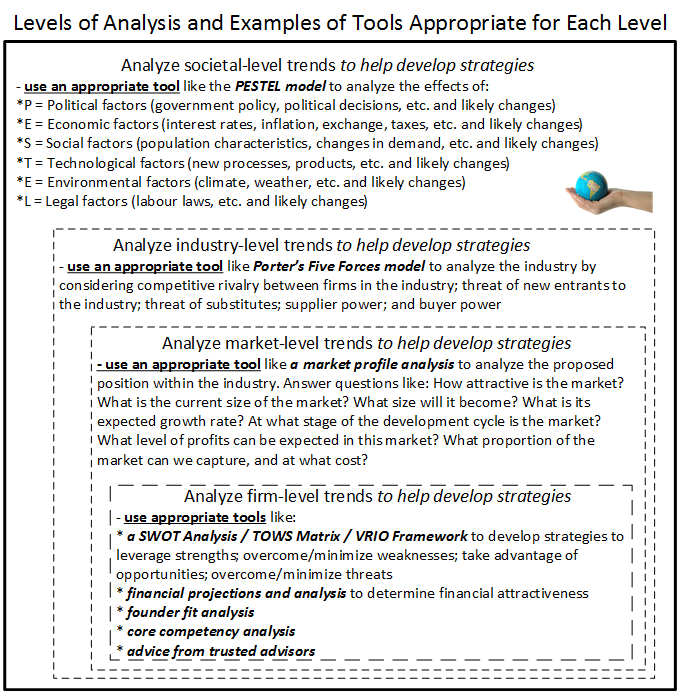

When evaluating entrepreneurial opportunities—sometimes called idea screening—an effective process involves assessing the various venture ideas being considered by applying different levels and types of analyses. Entrepreneurs starting ventures and running existing businesses should also regularly analyze their operating environments at the societal, industry, market, and firm-levels. The right tools, though, must be applied at each level of analysis (see Figure 5). It is critical to complete an Essential Initial Research at all four levels (societal, industry, market, and firm). The initial scan should be high-level, designed to assist in making key decisions (i.e. determining if there is a viable market opportunity for the venture). Secondary scans should be continuously conducted to support each part of the business plan (i.e. operations, marketing, finance). However, information should only be included if it is research-based, relevant, and value-adding. The results from such research (i.e. the Bank of Canada indicates that interest rates will be increasing in the next two years) should support business strategies within the plan (i.e. debt financing may be less favourable than equity financing). Often, obtaining support data (i.e. construction quotes) is not immediate, so plant a flag and move forward. Useful resources may include information from Statistics Canada, Bank of Canada, IBIS World Report, etc.

Societal Level

At a societal level, it is important to understand each of the political, economic, social, technological, environmental, and legal (PESTEL) factors—and, more specifically, the trends affecting those factors—that will have an impact on a venture based on a particular idea. Some venture ideas might be screened-out and others might be worth pursuing at a particular time because of the trends occurring with those PESTEL factors. Avoid the use of technical jargon that may distract readers (i.e. rivalry among firms) and use simpler language (i.e. competitive environment).

Industry Level

Apply Porter’s (1985) Five Forces Model, or a similar tool designed to assess industry-level factors. This analysis will focus more specifically on the sector of the economy in which you intend to operate. Again, the right analysis tool must be used for the assessment to be effective and avoid technical jargon (i.e. threat of new entrants) and use simpler wording (i.e. difficulty of entering the market) or flip to an analysis of the threat (i.e. strategies to establish and maintain market share).

Market Level

At the market level, use a tool to generate information about the part of the industry in which your business will compete. This tool might be in the form of a set of questions designed to uncover information that you need to know to help develop plans to improve the success of your proposed venture.

Firm Level

At a firm level, both the internal organizational trends and the external market profile trends should both be analyzed. There are several tools for conducting an internal organizational analysis, and normally you should normally apply several of them.

Analyzing the Trends at Each Level

Figure 2 – Different Levels of Analysis (Illustration by Lee A. Swanson)

Analyze Societal-Level Trends

- Use an appropriate tool like the PESTEL model to assess both the current situation and the likely changes as they may affect you.

- Political factors – federal & provincial & municipal government policy, nature of political decisions, potential political changes, infrastructure plans, etc.

- Economic factors – interest rates, inflation rates, exchange rates, tax rates, GDP growth, health of the economy, etc.

- Social factors –population characteristics like age distribution and education levels, changes in demand for types of products and services, etc.

- Technological factors – new processes, new products, infrastructure, etc.

- Environmental factors – effects of climate/weather, water availability, smog and pollution issues, etc.

- Legal factors – labour laws, minimum wage rates, liability issues, etc.

- Assess the impact these trends have upon the venture:

- Do the trends uncover opportunities and threats?

- Can opportunities be capitalized on?

- Can problems be mitigated?

- Can the venture be sustained?

Analyze Industry-Level Trends

- Use an appropriate tool like the Five Forces Model (Porter, 1985) to analyze the industry in which you expect to operate.

- Horizontal relationships – threat of substitutes, rivalry among existing competitors, threat of new entrants

- Vertical Relationships – bargaining power of buyers, bargaining power of suppliers

Analyze Market-Level Trends

- Use an appropriate method like a market profile analysis to assess the position within the industry in which you expect to operate.

- Determine the answers to questions like the following:

- How attractive is the market?

- In what way are competitors expected to respond if you enter the market?

- What is the current size of the market and how large is it expected to be?

- What are the current and projected growth rates?

- At what stage of the development cycle is the market?

- What level of profits can be expected in the market?

- What proportion of the market can be captured? What will be the cost to capture this proportion and what is the cost to capture the proportion required for business sustainability?

- Determine the answers to questions like the following:

Prior to a new business start-up, the customers that the new business wishes to attract either already purchase the product or service from a competitor to the new business—or they do not yet purchase the product or service at all. A new venture’s customers, therefore, must come from one of two sources: they must a) be attracted away from existing (direct) competitors or b) be convinced to make different choices about where they spend their money so they purchase the new venture’s product or service instead of spending their money in other ways (with indirect competitors). An entrepreneur must decide from which source they will attract their customers, and how they will do so. They must understand the competitive environment.

According to Porter (1996), strategy is about doing different things than competitors or doing similar things but in different ways. To develop an effective strategy, an entrepreneur must understand the competition.

To understanding the competitive environment, entrepreneurs must do the following:

- determine who their current direct and indirect competitors are and who the future competitors will be

- understand the similarities and differences in quality, price, competitive advantages, and other factors their proposed business and the existing competitors

- establish whether they can offer different products or services—or the same products or services in different ways—to attract enough customers to meet their goals

- anticipate how the competitors will react in response to the new venture’s entry into the market

Analyze Firm-level Trends (organizational analysis)

There are several tools available for firm-level analysis, and usually several of them should be applied because they serve different purposes.

- Use an appropriate tool like a SWOT Analysis/TOWS Matrix to formulate and evaluate potential strategies to leverage organizational strengths, overcome/minimize weaknesses, take advantage of opportunities, and overcome/minimize threats. You will also need to do a financial analysis and take into account the founder fit and the competencies a venture should possess.

- SWOT analysis – identify organizational strengths and weaknesses and external opportunities and threats

- TOWS matrix – develop strategies to:

- leverage strengths to take advantage of opportunities

- leverage strengths to overcome threats

- mitigate weaknesses by taking advantage of opportunities

- mitigate weaknesses while minimizing the potential threats or the potential outcomes from threats

For analyzing a firm’s strategy, apply a VRIO Framework analysis.

- While conceptualizing the resource-based view (RBV) of the firm, Barney (1997) and Barney and Hesterly (2006) identified the following four considerations regarding resources and their ability to help a firm gain a competitive advantage. Together, the following four questions make up the VRIO Framework, which can help assess a firm’s capacity, determine what competencies a venture should have, and determine whether competences are valuable, rare, inimitable, and exploitable.

- Value – Is a particular resource (financial, physical, technological, organizational, human, reputational, innovative) valuable to a firm because it helps it take advantage of opportunities or eliminate threats?

- Rarity – Is a particular resource rare in that it is controlled by or available to relatively few others?

- Imitability – Is a particular resource difficult to imitate so that those who have it can retain cost advantages over those who might try to obtain or duplicate it?

- Organization – Are the resources available to a firm useful to it because it is organized and ready to exploit them?

Assess the financial attractiveness of the venture:

- Analyze similar firms in industry.

- Comparative ratio and financial analysis (see Vesper, 1996, p. 145-148) can help determine industry norm returns, turnover ratios, working capital, operating efficiency, and other measures of firm success.

- Project market share.

- Analyze the key industry players’ relative market share, and make judgments about how the proposed venture would fare within the industry.

- Use information from market profile analysis and key industry player analysis.

- Analyze Expected Margins.

- Involves projecting expected margins from venture

- Useful information might come from financial analysis, market profile analysis, and NAICS (North American Industry Classification System) codes (six digit codes used to identify an industry—first five digits are standardized in Canada, the United States, and Mexico—is gradually replacing the four digit SIC (Standard Industrial Classification) codes)

- Analyze break-even point.

- Involves using information from margin analysis to determine break even volume and break-even sales in dollars

- Is there sufficient volume to sustain the venture?

- Analyze Pro forma.

- Forecasting income and assets required to generate profits

- Analyze Sensitivity.

- What will be the likely impact if some assumed variable values change?

- Project Return on Investments (ROI).

- Projecting the ROI from undertaking the venture

- What is the opportunity cost of undertaking the venture?

Founder fit is an important consideration for entrepreneurs screening venture opportunities. While there are plenty of examples of entrepreneurs successfully starting all types of businesses, “technical capability can be an important if not all-important factor in pursuing ventures success” (Vesper, 1996, p. 149). Factors such as the experience, training, credentials, reputation, and social capital an entrepreneur has can play an important role in their success or failure in starting a new venture. Even when an entrepreneur can recruit expert help through business partners or employees, they may also need to possess technical skills required in that particular kind of business.

A common and useful way to help screen venture options is to seek input from experts, peers, mentors, business associates, and perhaps other stakeholders like potential customers and direct family members.