6.2 Gurus of Quality

Much of the field of Quality originated from several individuals who spent their careers researching, teaching and developing the field of Quality. These individuals are Walter Shewhart, W. Edwards Deming, Joseph Juran, Philip Crosby, and Armand Fiegenbaum.

Walter A. Shewhart (1891-1967): Pioneer of Statistical Quality Control

Dr. Shewhart, an American physicist, engineer, and statistician, is widely regarded as the father of statistical quality control (SQC). Throughout his career, he extensively researched process variation and is credited with developing the first control chart. His groundbreaking work centred on the importance of reducing variation to achieve quality improvement.

Shewhart’s legacy includes the fundamental concepts of assignable and common causes of variation. All production processes exhibit some level of variation, which intuitively leads to decreased quality with increased variability. Assignable variation arises from identifiable and addressable causes, such as employee error, software malfunction, or equipment failure. In contrast, common variation, also known as chance variation, is inherent to the process and generally expected. Minimizing or eliminating either type of variation directly translates to enhanced product quality.

W. Edwards Deming (1900-1993): Champion of Quality Management

Arguably the most prominent figure among the “Quality Gurus,” Dr. Deming was an American engineer, statistician, professor, and prolific author. Following World War II, his expertise in statistical process control led him to Japan, where he was recruited to aid with their national census. From 1950 onwards, Deming’s significant contribution involved training thousands of Japanese engineers, managers, and academics in fundamental statistical process control techniques. This pivotal role is widely credited with propelling Japan to become a global leader in quality manufacturing.

In recognition of Deming’s profound impact, the Deming Prize, Japan’s most prestigious quality award, was named in his honour. While Dr. Deming authored numerous publications, his enduring legacy is likely secured through his renowned Deming’s 14 Points and the Deming Cycle, both of which continue to be foundational principles within quality management practices.

Edwards Deming’s “14 Points:”

- Create constancy of purpose toward improvement of product and service, with the aim to become competitive, to stay in business and to provide jobs.

- Adopt the new philosophy. We are in a new economic age. Western management must awaken to the challenge, learn their responsibilities, and take on leadership for change.

- Cease dependence on inspection to achieve quality. Eliminate the need for massive inspection by building quality into the product in the first place.

- End the practice of awarding business on the basis of a price tag. Instead, minimize total cost. Move towards a single supplier for any one item, on a long-term relationship of loyalty and trust.

- Improve constantly and forever the system of production and service to improve quality and productivity, and thus constantly decrease costs.

- Institute training on the job.

- In Institute leadership, the aim of supervision should be to help people and machines and gadgets do a better job. Supervision of management is in need of overhaul, as well as supervision of production workers.

- Drive out fear so that everyone may work effectively for the company.

- Break down barriers between departments. People in research, design, sales, and production must work as a team to foresee problems of production and usage that may be encountered with the product or service.

- Eliminate slogans, exhortations, and targets for the workforce, asking for zero defects and new levels of productivity. Such exhortations only create adversarial relationships, as the bulk of the causes of low quality and low productivity belong to the system and thus lie beyond the power of the workforce.

- Eliminate work standards (quotas) on the factory floor. Substitute with leadership.

- Eliminate management by objective. Eliminate management by numbers and numerical goals. Instead, substitute with leadership.

- Remove barriers that rob the hourly worker of his right to pride of workmanship. The responsibility of supervisors must be changed from sheer numbers to quality.

- Remove barriers that rob people in management and engineering of their right to pride of workmanship.

- Institute a vigorous program of education and self-improvement.

- Put everybody in the company to work to accomplish the transformation. The transformation is everybody’s job.

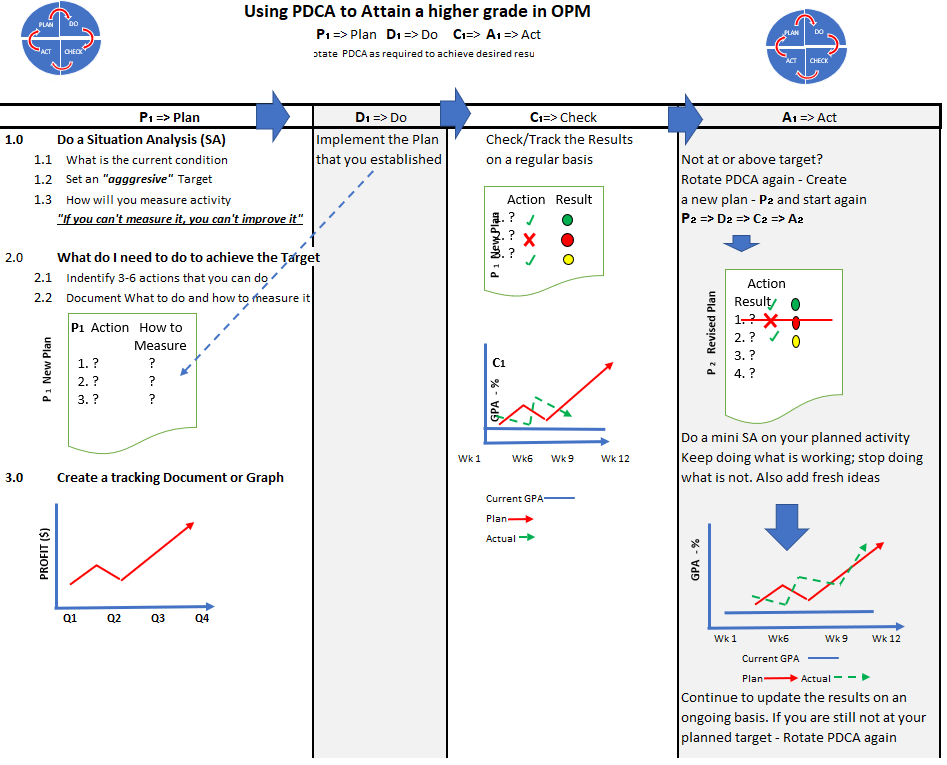

The Deming Cycle or Deming Wheel is also known as PDCA, or “Plan, Do Check, Act.” It is a version of continuous improvement that emphasizes the continuous nature of process improvement.

Accessible format for Figure 6.2.1

Image Description

Figure 6.2.1 shows a diagram that is divided into four main sections labelled Plan (P1), Do (D1), Check (C1), and Act (A1), each represented by arrows flowing sequentially from one to the next, forming a continuous loop. The diagram emphasizes the iterative nature of the PDCA cycle, with smaller versions of the PDCA cycle shown at the top corners.

- Plan (P1):

- Do a Situation Analysis (SA):

- 1.1 What is the current condition?

- 1.2 Set an aggressive target.

- 1.3 How will you measure the activity? (Quote: “If you can’t measure it, you can’t improve it”)

- What do I need to do to achieve the target?

- 2.1 Identify 3-6 actions that you can take.

- 2.2 Document what to do and how to measure it.

- Create a tracking document or graph:

- Example graph shows progress over four quarters (Q1 to Q4) with a rising trend.

- Do a Situation Analysis (SA):

- Do (D1):

- Implement the Plan that you established

- Check (C1):

- Check/Track the Results on a regular basis: Track progress using a document or graph.

- Act (A1):

- Not at or above target? Rotate PDCA again:

- Create a new plan (P2) and start again.

- Do a mini SA on your planned activity.

- Keep doing what is working; stop doing what is not.

- Add fresh ideas.

- Continue to update the results on an ongoing basis.

- If you are still not at your planned target – Rotate PDCA again.

- Not at or above target? Rotate PDCA again:

Joseph M. Juran (1904-2008): Quality Management Authority

Juran, a Romanian-born American engineer, established himself as a giant in the quality management field. His foundational work includes the widely influential Quality Control Handbook, first published in 1951. Juran championed a three-pronged approach to quality, known as the Juran Trilogy: quality planning, quality control, and quality improvement. A prolific author, he contributed hundreds of papers and 12 books to the field. Notably, Juran is credited with the concept of the cost of quality, a framework for understanding and managing the financial implications of quality.

Juran’s influence extends beyond his own contributions. He recognized the value of Vilfredo Pareto’s (1848-1923) work and popularized the Pareto Principle, also known as the 80/20 rule. This principle, originally an observation by Pareto that 80% of Italy’s land was owned by 20% of the population, has become a cornerstone of problem-solving and continuous improvement efforts in quality management. The principle suggests that a significant portion of problems (around 80%) often stem from a relatively small number of root causes (around 20%). This realization allows organizations to focus their improvement efforts on the most impactful areas.

The Pareto Principle finds numerous applications within quality management:

- Defect concentration: It’s widely accepted that 80% of defects can be traced back to a small number (20%) of root causes. Firms benefit by prioritizing the identification and rectification of these root causes.

- Profit distribution: In many companies, 80% of profits might be generated by just 20% of the products or services offered. Identifying and nurturing these high-performing offerings can significantly improve overall profitability.

- Employee engagement: Sometimes, just 20% of employees might be responsible for generating 80% of the continuous improvement ideas. Recognizing and encouraging these valuable contributors can foster a culture of innovation within the organization.

Philip Crosby (1926-2001): Champion of “Zero Defects”

Crosby, an American businessman and author, gained recognition for his 1979 book Quality is Free. He challenged the prevailing notion that quality comes at a premium, arguing instead that the true costs of quality are often significantly underestimated. Crosby is credited with coining the term zero defects, a philosophy emphasizing the elimination of errors from the outset. He maintained that preventing defects is far more cost-effective than relying on extensive inspection, rework, and repairs after the fact.

Armand Feigenbaum (1920-2014): Architect of Total Quality Management

Dr. Feigenbaum, an American quality engineer and businessman, served as the Director of Manufacturing Operations at General Electric from 1958 to 1968. He is credited with pioneering the concept of total quality control, which later evolved into the widely adopted total quality management (TQM) philosophy. Feigenbaum also introduced the thought-provoking concept of the “hidden plant“, which refers to the untapped productive capacity lost due to inefficiencies, defects, and rework. His work highlighted the significant potential for improvement that lies within existing operations.

“5 Managing Quality” from Introduction to Operations Management Copyright © by Hamid Faramarzi and Mary Drane is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.—Modifications: used section Gurus of Quality, some paragraphs rewritten; images added.