Chapter 13: Interpersonal Relationships at Work

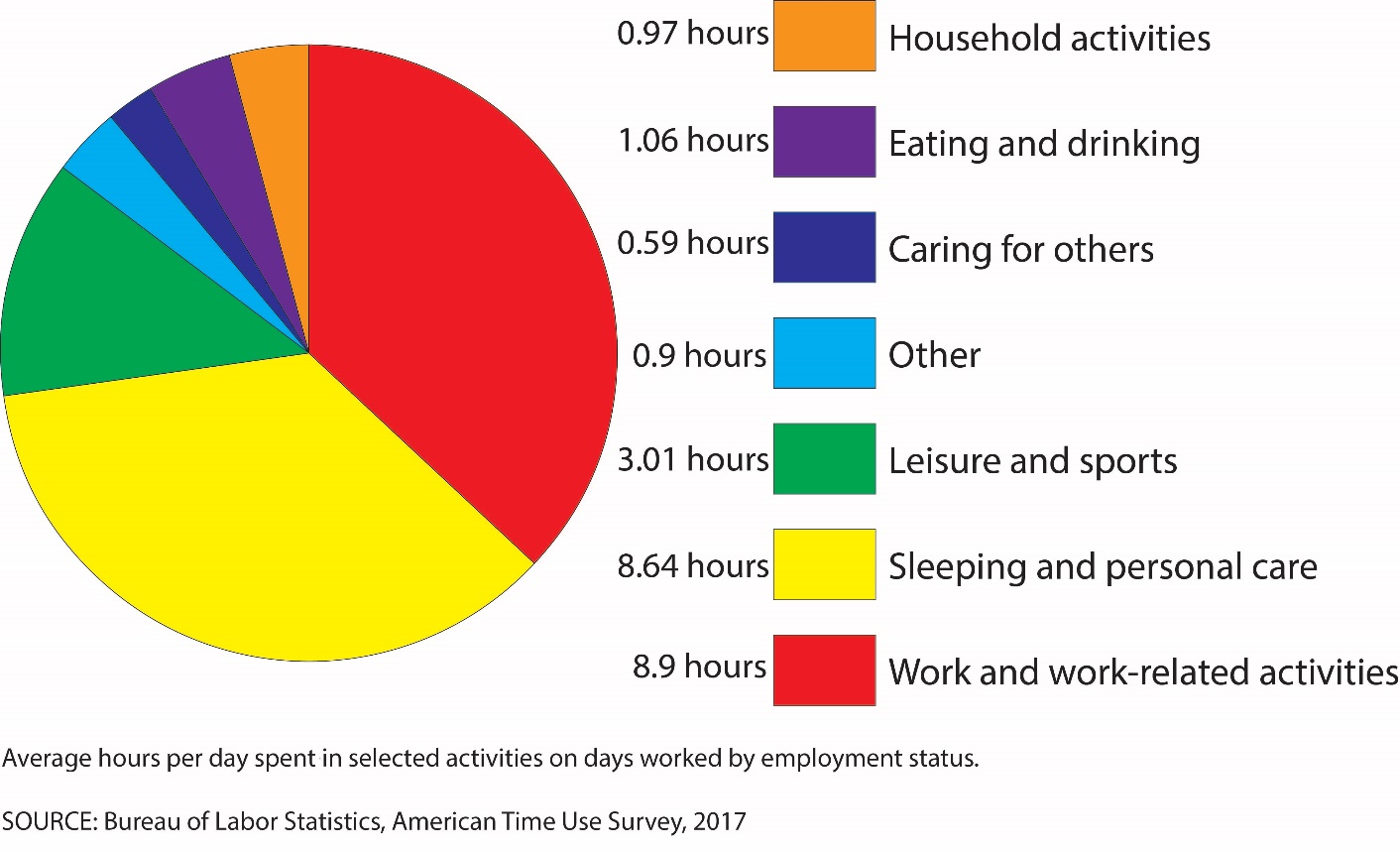

Second to spending time with your family, you’ll probably end up spending more time working than anything else you do for the rest of your life (besides sleeping). Figure 13.1 shows you what the average full-time working person’s day is like.

We spend more time with the people we work with than the people we live with during the five-day workweek. So, it shouldn’t be too surprising that our workplace relationships tend to be very important to our overall quality of life. In previous chapters, we’ve looked at the importance of a range of different types of relationships. In this chapter, we’re going to explore some areas directly related to workplace interpersonal relationships, including professionalism, leader-follower relationships, workplace friendships, romantic relationships in the workplace, and problematic workplace relationships. Finally, we’ll end this chapter by discussing essential communication skills for work in the 21st Century.

13.1 The Requirements of Professionalism

Learning Objectives

- Define the terms profession and professionalism.

- Define the term “ethics” and recall several modern ethical lapses in organizations.

- Understand the importance of respecting one’s coworkers.

- Explain the concept of personal responsibility in the workplace.

- Differentiate between formal and informal language.

What is professionalism? A profession is an occupation that involves mastery of complex knowledge and skills through prolonged training, education, or practical experience. Becoming a member of a specific profession doesn’t happen overnight. Whether you seek to be a public relations expert, lawyer, doctor, teacher, welder, electrician, and so on, each profession involves that interested parties invest themselves in learning to become a professional or a member of a profession who earns their living through specified expert activity. It’s much easier to define the terms “profession” and “professional” than it is to define the term “professionalism” because each profession will have its take on what it means to be a professional within a given field.

According to the United States Department of Labor,1 professionalism “does not mean wearing a suit or carrying a briefcase; rather, it means conducting oneself with responsibility, integrity, accountability, and excellence. It means communicating effectively and appropriately and always finding a way to be productive.” The U.S. Department of Labor’s book Skills to Pay the Bills: Mastering Soft Skills for Workplace Success goes on to note:

Professionalism isn’t one thing; it’s a combination of qualities. A professional employee arrives on time for work and manages time effectively. Professional workers take responsibility for their own behavior and work effectively with others. High quality work standards, honesty, and integrity are also part of the package. Professional employees look clean and neat and dress appropriately for the job. Communicating effectively and appropriately for the workplace is also an essential part of professionalism.2

The Requirements of Professionalism

As you can see here, professionalism isn’t a single “thing” that can be labeled. Instead, professionalism involves the aims and behaviors that demonstrate an individual’s level of competence expected by a professional within a given profession. By the word “aims,” we mean that someone who exhibits professionalism is guided by a set of goals in a professional setting. Whether the aim is to complete a project on time or help ensure higher quarterly incomes for their organization, professionalism involves striving to help one’s organization achieve specific goals. By “behaviors,” we mean specific ways of behaving and communicating within an organizational environment. Some common behaviors can include acting ethically, respecting others, collaborating effectively, taking personal/professional responsibility, and professionally using language. Let’s look at each of these separately.

Ethics

Every year there are lapses in ethical judgment by organizations and organizational members. For our purposes, let’s look at just two years of ethical lapses.

- We saw aviation police officers drag a bloodied pulmonologist off a plane when he wouldn’t give up his seat on United Airlines.

- We saw the beginnings of the #MeToo movement in October 2017 after Alyssa Milano uses the hashtag in response to actor Ashley Judd accusing media mogul Harvey Weinstein of serious sexual misconduct in an article within The New York Times. Since that critical moment, many courageous victims of sexual violence have raised their voices to take on the male elites in our society who had gotten away with these behaviors for decades.[1]

- Facebook (among others) was found to have accepted advertisements indirectly paid for by the Kremlin that influenced the 2016 election. The paid advertisements constituted a type of cyber warfare.

- Equifax had a data breach that affected 145 million people (mostly U.S. citizens as well as some British and Canadian customers) and didn’t publicly disclose this for two months.

- The head of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Scott Pruitt, committed many ethical lapses during his tenure with the agency prompting his resignation. Some of the ethical lapses included ordering raises for two aides even when White House rejected them, spending $3.5 million (twice times as much as his predecessor) on taxpayer-funded security, using that security to pick up his favorite moisturizing lotion and dry-cleaning, renting a room from a lobbyist who had dealings with the EPA for $50 per night, installing a $43,000 private phone booth in his office that allegedly was used once, spending $124,000 on first-class flights, purchasing two season-ticket seats at a University of Kentucky basketball game from a billionaire coal executive, tried to use his position to get his wife a Chick-fil-A franchise, and others.

Sadly, these ethical lapses are still frequent in corporate America, and they often come with huge lawsuit settlements and/or jail time.

The word “ethics” actually is derived from the Greek word ethos, which means the nature or disposition of a culture.3 From this perspective, ethics then involves the moral center of a culture that governs behavior. Without getting too deep, let’s just say that philosophers debate the very nature of ethics, and they have described a wide range of different philosophical perspectives on what constitutes ethics. For our purposes, ethics is the judgmental attachment to whether something is good, right, or just.

In the business world, we often talk about business ethics, which involves things like not stealing from a company; not lying to one’s boss, coworkers, or customers/clients; not taking bribes, payoffs, or kickbacks; taking credit for someone else’s work; abusing and belittling someone in the workplace; or simply letting other people get away with unethical behavior. For example, if you know your organization has a zero-tolerance policy for workplace discrimination and you know that one supervisor is purposefully not hiring pregnant women because “they’ll just be leaving on maternity leave soon anyway,” then you are just as responsible as that supervisor. We might also add, that discriminating against someone who is pregnant or can get pregnant is also a violation of Equal Employment Opportunity law, so you can see that often the line between ethics and rules (or laws) can be blurred.

From a communication perspective, there are also ethical issues that you should be aware of. W. Charles Redding, the father of organizational communication, broke down unethical organizational communication into six specific categories.4

| Reprinted with permission from Wrench, Punyanunt, and Ward’s (2014, Flat World Knowledge) book Organizational communication: Practice, Research, and Theory. | |

| An organizational communication act is unethical if it is… | Such organizational communication unethically… |

|---|---|

| coercive |

|

| destructive |

|

| deceptive |

|

| intrusive |

|

| secretive |

|

| manipulative/exploitative |

|

Table 13.1. Redding’s Typology of Unethical Communication

As you can see, unethical organizational communication is an area many people do not overly consider.

Respect for Others

Our second category related to professionalism is respecting others. In Disney’s 1942 movie, Bambi, Thumper sees the young Bambi learning to walk, which leads to the following interaction with his mother:

Thumper: He doesn’t walk very good, does he?

Mrs. Rabbit: Thumper!

Thumper: Yes, mama?

Mrs. Rabbit: What did your father tell you this morning?

Thumper: If you can’t say something nice, don’t say nothing at all.

Sadly, many people exist in the modern workplace that need a refresher in respect from Mrs. Rabbit today. From workplace bullying to sexual harassment, many people simply do not always treat people with dignity and respect in the workplace. So, what do we mean by treating someone with respect? There are a lot of behaviors one can engage in that are respectful if you’re interacting with a coworker or interacting with leaders or followers. Here’s a list we created of respectful behaviors for workplace interactions:

- Be courteous, polite, and kind to everyone.

- Do not criticize or nitpick at little inconsequential things.

- Do not engage in patronizing or demeaning behaviors.

- Don’t engage in physically hostile body language.

- Don’t roll your eyes when your coworkers are talking.

- Don’t use an aggressive tone of voice when talking with coworkers.

- Encourage coworkers to express opinions and ideas.

- Encourage your coworkers to demonstrate respect to each other as well.

- Listen to your coworkers openly without expressing judgment before they’ve finished speaking.

- Listen to your coworkers without cutting them off or speaking over them.

- Make sure you treat all of your coworkers fairly and equally.

- Make sure your facial expressions are appropriate and not aggressive.

- Never engage in verbally aggressive behavior: insults, name-calling, rumor mongering, disparaging, and putting people or their ideas down.

- Praise your coworkers more often than you criticize them. Point out when they’re doing great things, not just when they’re doing “wrong” things.

- Provide an equal opportunity for all coworkers to provide insight and input during meetings.

- Treat people the same regardless of age, gender, race, religion, sex, sexual orientation, etc.…

- When expressing judgment, focus on criticizing ideas, and not the person.

Now that we’ve looked a wide range of ways that you can show your respect for your coworkers, we would be remiss if we didn’t bring up one specific area where you can demonstrate respect, the language we use. In a recent meeting, one of our coauthors was reporting on some work that was being completed on campus and let people in the meeting know that some people were already “grandfathered in” to the pre-existing process. Without really intending to use language that was sex-based, our coauthor had. One of the other people in the room quickly quipped, “or grandmothered.” Upon contemplation, our coauthor realized that the seemingly innocuous use of the phrase “grandfathered in,” which admittedly is very common, is one that has a biological sex connotation that limits it to males. Even though our coauthor’s purpose had never been to engage in sexist language, the English language is filled with sexist language examples, and they come all too quickly to many of us because of tradition and the way we were taught the language. This experience was a perfect reminder for our coauthor about the importance of thinking about sexist and biased language and how it impacts the workplace. Table 13.2 is a list of common sexist or biased language and corresponding inclusive terms that one could use instead.

| Sexist or Biased Language | Inclusive Term |

|---|---|

| Businessman | business owner, business executive, or business person |

| cancer victim; AIDS victim | cancer patient; person living with AIDS |

| chairman | chairperson or chair |

| confined to a wheelchair | uses a wheelchair |

| congressman | congressperson |

| Eskimo | Inuit or Aleut |

| fireman | firefighters |

| freshman | first-year student |

| Indian (when referring to U.S. indigenous peoples) | Native American or specific tribe |

| policeman | police officer |

| man or mankind | people, humanity, or the human race |

| man hours | working hours |

| man-made | manufactured, machine made, or synthetic |

| manpower | personnel or workforce |

| Negro or colored | African American or Black |

| old people or elderly | senior citizens, mature adults, older adults |

| Oriental | Asian, Asian American, or specific country of origin |

| postman or mailman | postal worker or mail carrier |

| steward or stewardess | flight attendant |

| suffers from diabetes | has diabetes |

| to man | to operate; to staff; to cover |

| waiter or waitress | server |

Table 13.2. Replacing Sexist or Biased Language with Inclusive Terms

Mindfulness Activity

We live in a world where respect and bias are not always acknowledged in the workplace setting. Sadly, despite decades of anti-discrimination legislation and training, we know this is still a problem. Women, minorities, and other non-dominant groups are still woefully underrepresented in a broad range of organizational positions, from management to CEO. Some industries are better than others, but this problem is still very persistent in the United States. Most of us mindlessly participate in these systems without even being consciously aware. Byron Lee put it this way:

Our brains rapidly categorize people using both obvious and subtler characteristics, and also automatically assign an unconscious evaluation (eg good or bad) and an emotional tone (ie pleasant, neutral or unpleasant) with this memory. Importantly, because these unconscious processes happen without awareness, control, intention or effort, everyone, no matter how fair-minded we might think we are, is unconsciously biased.5

These unconscious biases often lead us to engage in microaggressions against people we view as “other.” Microaggressions are “the everyday verbal, nonverbal, and environmental slights, snubs, or insults, whether intentional or unintentional, which communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative messages to target persons based solely upon their marginalized group membership.”6 Notice that microaggressions can be targeted at women, minorities, and other non-dominant groups. Research has shown us that these unconscious biases effect everything from perceptions of hire ability, to job promotions, to determining who gets laid off, and so many other areas within the workplace.

Byron Lee devised a five-point strategy for engaging in mindful intercultural interactions:

- Preparing for your interpersonal encounter by recognizing and gently observing preconceptions, biases, emotions and sensations as part of your ongoing internal experience (Nonjudging). Bringing into awareness an intention to connect (Presence).

- Beginning your conversation by remaining open to hear whatever the person may bring (Acceptance), and a willingness to get close to and understand another’s suffering (Empathic Concern).

- Bringing a kindly curiosity to your own internal experience and to the experiences shared by the other person throughout the encounter (Beginner’s Mind).

- Noticing and letting go of your urge to ‘fix’ the ‘problem’ (Non-striving) and letting the process unfold in its own time (Patience).

- The collaborative interaction concludes when you mutually reach a way forward that reflects the other person’s world view and needs (Compassionate Action), and not your own (Letting Go).7

For this activity, we want you to explore some of your own unconscious biases. To start, go to the Implicit Bias Tests website run by Harvard University’s Project Implicit. On their website, you’ll find several tests that examine your unconscious or implicit biases towards various groups. Complete a couple of these tests and then ponder what your results say about your own unconscious biases. After completing the tests, answer the following questions:

- Were you surprised by your scores on the Implicit Bias Tests? Why?

- How do you think your own implicit biases impact how you interact with others interpersonally?

- How can you be more mindful of your interactions with people from different groups in the future?

Personal Responsibility

Let’s face it; we all make mistakes. Making mistakes is a part of life. Personal responsibility refers to an individual’s willingness to be accountable for what they feel, think, and behave. Whether we’re talking about our attitudes, our thought processes, or physical/communicative behaviors, personal responsibility is simply realizing that we are in the driver’s seat and not blaming others for our current circumstances. Now, this is not to say that there are never external factors that impede our success. Of course, there are. This is not to say that certain people have a leg-up on life because of a privileged background, of course, some people have. However, personal responsibility involves differentiating between those things we can control and those things that are outside of our control. For example, I may not be able to control a coworker who decides to yell at me, but I can control how I feel about that coworker, how I think about that coworker, and how I choose to respond to that coworker. Here are some ways that you can take personal responsibility in your own life (or in the workplace):

- Acknowledge that you are responsible for your choices in the workplace.

- Acknowledge that you are responsible for how you feel at work.

- Acknowledge that you are responsible for your behaviors at work.

- Accept that your choices are yours alone, so you can’t blame someone else for them.

- Accept that your sense of self-efficacy and self-esteem are yours.

- Accept that you can control your stress and feelings of burnout.

- Decide to invest in your self-improvement.

- Decide to take control of your attitudes, thoughts, and behaviors.

- Decide on specific professional goals and make an effort and commitment to accomplish those goals.

Although you may have the ability to take responsibility for your feelings, thoughts, and behaviors, not everyone in the workplace will do the same. Most of us will come in contact with coworkers who do not take personal responsibility. Dealing with coworkers who have a million and one excuses can be frustrating and demoralizing.

Excuse-making occurs any time an individual attempts to shift the blame for an individual’s behavior from reasons more central to the individual to sources outside of their control in the attempt to make themselves look better and more in control.8 For example, an individual may explain their tardiness to work by talking about how horrible the traffic was on the way to work instead of admitting that they slept in late and left the house late. People make excuses because they fear that revealing the truth would make them look bad or out of control. In this example, waking up late and leaving the house late is the fault of the individual, but they blame the traffic to make themself look better and in control even though they were late.

Excuse-making happens in every facet of life, but excuse-making in the corporate world can be highly problematic. For example, research has shown that when front-line service providers engage in excuse-making, they are more likely to lose return customers as a result.9 In one study, when salespeople attempted to excuse their lack of ethical judgment on their customer’s lack of ethics, supervisors tended to punish more severely those who engaged in excuse-making than those who had not.10 Of course, even an individual’s peers can become a little annoyed (or downright disgusted) by a colleague who always has a handy excuse for their behavior. For this reason, Amy Nordam recommends using the ERROR method when handling a situation where your behavior was problematic: Empathy, Responsibility, Reason, Offer Reassurance.11 Here is an example Nordam uses to illustrate the ERROR method:

I hate that you [burden placed on person] because of me (Empathy). I should have thought things out better (Responsibility), but I got caught up in [reason for behavior] (Reason). Next time I’ll [preventative action] (Offer Reassurance).

As you can see, the critical parts of this response involve validating the other person, taking responsibility, and providing an explanation for how you’ll behave in the future to avoid similar problems.

Language Use

In the workplace, the type of language and how we use language is essential. In a 2016 study conducted by PayScale,12 researchers surveyed 63,924 managers. The top 3 Hard-Skills managers reported that new college graduates lack are writing proficiency (44%), public speaking (39%), and data analysis (36%). The top 3 Soft Skills the managers reported that new college graduates lack are critical thinking/problem-solving (60%), attention to detail (56%), and communication (46%). One of the most important factors of professionalism in today’s workplace is effective written and oral communication. From the moment someone sends in a resume with a cover letter, their language skills are being evaluated, so knowing how to use both formal language effectively and jargon/specialized language is paramount for success in the workplace.

Formal Language

Formal language is a specific writing and spoken style that adheres to strict conventions of grammar. This is in contrast to informal language, which is more common when we speak. In the workplace, there are reasons why someone would use both formal and informal language. Table 13.3 provides examples of formal and informal language choices.

| Characteristic | Informal | Formal |

|---|---|---|

| Contraction | I won’t be attending the meeting on Friday. | I will not be attending the meeting on Friday. |

| Phrasal Verbs | The report spelled out the need for more resources. | The report illustrated the need for more resources. |

| Slang/ Colloquialism |

The nosedive in our quarterly earnings came out of left field. | The downturn in our quarterly earnings was unexpected. |

| First-Person Pronouns | I considered numerous research methods before deciding to use an employee satisfaction survey. | Numerous research methods were considered before deciding to use an employee satisfaction survey. |

| We need to come together to complete the organization’s goals. | The people within the organization must work towards the organization’s goals. |

Table 13.3 Formal and Informal Language Choices

As you can see from Table 13.3, formal language is less personal and more professional in tone than informal language. Some key factors of formal language include complex sentences, use of full words, and the third person. Informal language, on the other hand, is more colloquial or common in tone; it contains simple, direct sentences; uses contractions and abbreviations, and allows for a more personal approach that includes emotional displays. For people entering the workplace, learning how to navigate both formal and informal language is very beneficial because different circumstances will call for both in the workplace. If you’re writing a major report for shareholders, then knowing how to use formal language is very important. On the other hand, if you’re a PR professional speaking on behalf of an organization, speaking to the media using formal language could make you (and your organization) look distant and disconnected, so using informal language can help in this case.

Use of Jargon/Specialized Language

Every industry is going to be filled with specialized jargon or the specialized or technical language particular to a specific profession, occupation, or group that is either meaningless or difficult for outsiders to understand. For example, if I informed that we conducted a “factor analysis with a varimax rotation,” most of your heads would immediately start to spin. However, for those of us who study human communication from a social scientific perspective, we would all know what that phrase means because we learned it during our training in graduate school. If you walked into a hospital and heard an Emergency Department (ED) physician referring to the GOMER in bay 9, most of you would be equally perplexed. Every job has some jargon, so part of being a professional is learning the jargon within your industry and peripherally related sectors as well. For example, if you want to be a pharmaceutical sales representative, learning some of the jargon of an ED (notice they’re not called ERs anymore). Trust us, watching the old television show ER isn’t going to help you learn this jargon very well either.13

Instead, you have to spend time within an organization or field to pick up the necessary jargon. However, you can start this process as an undergraduate by joining student groups associated with specific fields. If you want to learn the jargon of public relations, join the Public Relations Student Society of America. If you want to go into training and development, becoming a student member of the Association for Talent Development. Want to go into nonprofit work, become a member of the Association for Volunteer Administration or the Young Nonprofit Professionals Network. If you do not have a student chapter of one of these groups on your campus, then find a group on LinkedIn or another social networking site aimed at professionals. One of the great things about modern social networking is the ability to watch professionals engaging in professional dialogue virtually. By watching the discussions in LinkedIn groups, you can start to pick up on the major issues of a field and some of the everyday jargon.

Key Takeaways

- A profession is an occupation that involves mastery of complex knowledge and skills through prolonged training, education, or practical experience. Professionalism, on the other hand, involves the aims and behaviors that demonstrate an individual’s level of competence expected by a professional within a given profession.

- The term ethics is defined as the judgmental attachment to whether something is good, right, or just. In our society, there have been several notable ethical lapses, including such companies as United Airlines, Facebook, Equifax, and the Environmental Protection Agency. Starting in Fall 2017 the #MeToo movement started shining a light on a wide range of ethical issues involving the abuse of one’s power to achieve sexual desires in the entertainment industry.

- Respecting our coworkers is one of the most essential keys to developing a positive organizational experience. There are many simple things we can do to show our respect, but one crucial feature is thinking about the types of langue we use. Avoid using language that is considered biased and marginalizing.

- Personal responsibility refers to an individual’s willingness to be accountable for what they feel, think, and behave. Part of being a successful coworker is taking responsibility for your behaviors, communication, and task achievement in the workplace.

- Formal language is a specific writing and spoken style that adheres to strict conventions of grammar. Conversely, informal language is more colloquial or common in tone; it contains simple, direct sentences; uses contractions and abbreviations, and allows for a more personal approach that includes emotional displays.

Exercises

- Think of a time in an organization where you witnessed unethical organizational communication. Which of Redding’s typology did you witness? Did you do anything about the unethical organizational communication? Why?

- Look at the list of respectful behaviors for workplace interactions. How would you react if others violated these respectful behaviors towards you as a coworker? Have you ever been disrespectful in your communication towards coworkers? Why?

- Why do you think it’s essential to take personal responsibility and avoid excusing making in the workplace? Have you ever found yourself making excuses? Why?

13.2 Leader-Follower Relationships

Learning Objectives

- Visual and explain Hersey and Blanchard’s situational-leadership theory, including the four types of leaders.

- Describe the concept of leader-member exchange theory and the three stages these relationships go through.

- Define Ira Chaleff’s concept of followership and describe the four different followership styles.

Perspectives on Leadership

When you hear the word “leader” what immediately comes to your mind? What about when you hear the word “follower?” The words “leader” and “follower” bring up all kinds of examples (both good and bad) for most of us. We’ve all experienced times when we’ve followed a fantastic leader, and we’ve had times when we’ve worked for a less than an effective leader. At the same time, are we always the best followers? This section is going to examine prevailing theories related to leadership (situational-leadership theory and leader-member exchange theory), and then we’ll end the section discussing the concept of followership.

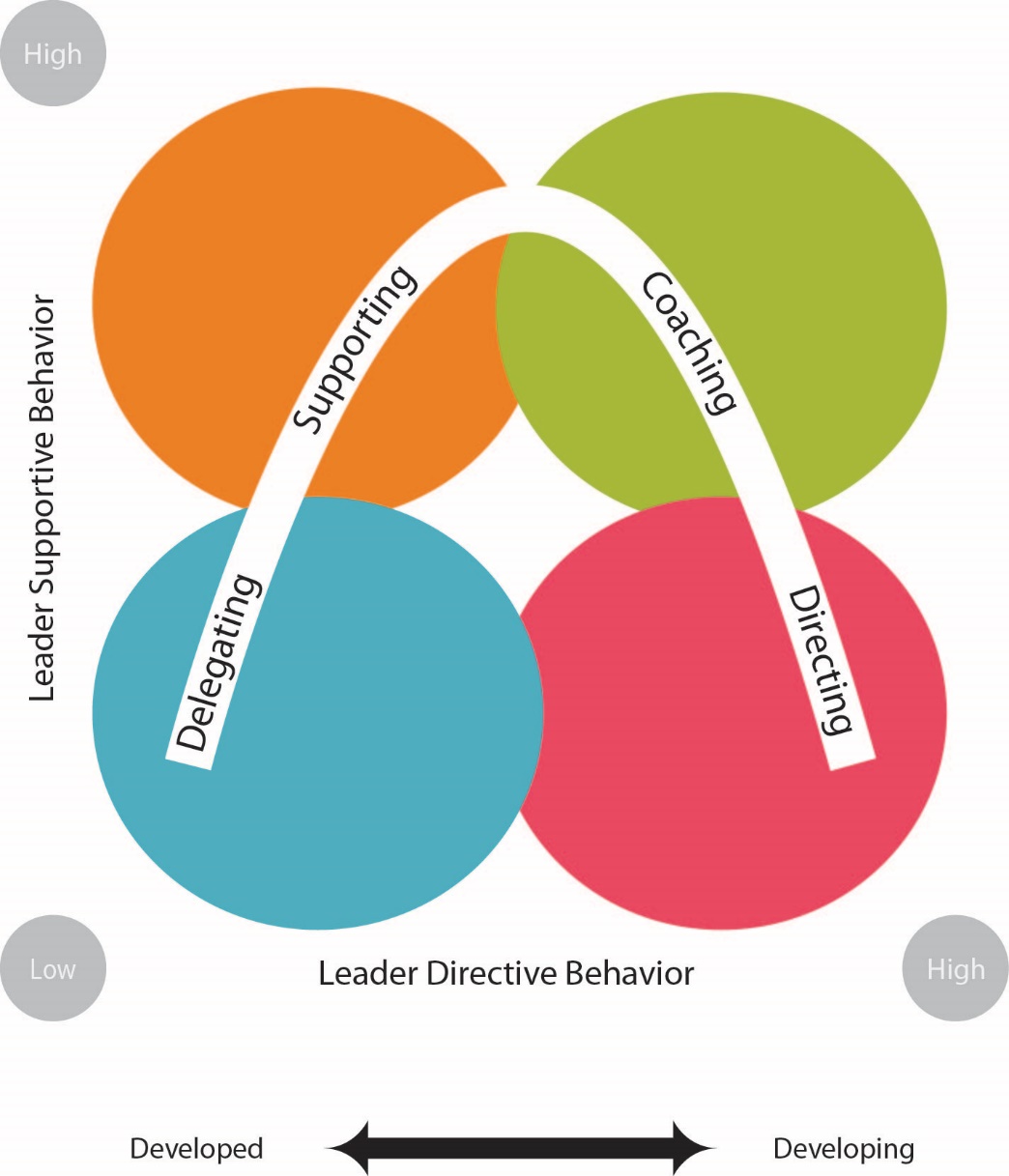

Hersey and Blanchard’s Situational-Leadership Theory

One of the most commonly discussed models of leadership is Paul Hersey and Kenneth Blanchard Situational-Leadership Model (https://www.situational.com/). The model is divided into two dimensions: task (leader directive behavior) and relational (leader supportive behavior).14 Hersey and Blanchard’s Situational-Leadership Model starts with the basic idea that not all employees have the same needs. Some employees need a lot more hand-holding and guidance than other employees, and some employees need more relational contact than others. As such, Hersey and Blanchard defined leadership along two continuums: supportive and directive. Supportive leadership behavior occurs when a leader is focused on providing relational support for their followers; whereas, directive support involves overseeing the day-to-day tasks that a follower accomplishes. As a leader and follower progress in their relationship, Hersey and Blanchard argue that the nature of their relationship often changes. Figure 13.2 contains the basic model proposed by Hersey and Blanchard and is ultimately broken into four leadership styles: directing, coaching, supporting, and delegating.15

Directing

Hersey and Blanchard’s first type of leader is the directing leader. Directing leaders set the basic roles an individual has and the tasks an individual needs to accomplish. After setting these roles and tasks, the leader then monitors and oversees these followers closely. From a communication perspective, these leaders tend to make decisions and then communicate them to their followers. There tends to be little to no dialogue about either roles or tasks.

Coaching

Hersey and Blanchard’s second type of leader is the coaching leader. Coaching leaders still set the basic roles and tasks that need to be accomplished by specific followers, but they allow for input from their followers. As such, the communication between coaching leaders and their followers tends to be more interactive instead of one-way. However, the ultimate decisions about roles and tasks are still ultimately the leader’s decision.

Supporting

Hersey and Blanchard’s third type of leader is the supporting leader. As a leader becomes more accustomed to a follower’s ability to accomplish tasks and take responsibility for those tasks, a leader may become more supportive. A supporting leader allows followers to make the day-to-day decisions related to getting tasks accomplished, but determining what tasks need to be accomplished is a mutually agreed upon decision. In this case, the leader is more like a facilitator of a follower’s work instead of dictating the follower’s work.

Delegating

Hersey and Blanchard’s final type of leader is the delegating leader. The delegating leader is one where the follower and leader are mutually involved in the basic decision making and problem-solving process. Still, the ultimate control for accomplishing tasks is left up to the follower. Followers ultimately determine when they need a leader’s support and how much support is needed. As you can see from Figure 13.2, these relationships are ones that are considered highly developed and ultimately involve a level of trust on both sides of the leader-follower relationship.

Leader-Member Exchange Relationships

George Graen16 proposed a different type of theory for understanding leadership. In Graen’s leader-member exchange (LMX) theory, leaders have limited resources and can only take on high-quality relationships with a small number of followers. For this reason, some relationships are characterized as high-quality LMX relationships, but most relationships are characterized as low-quality LMX relationships. High-quality LMX relationships are those “characterized by greater input in decisions, mutual support, informal influence, trust, and greater negotiating latitude.”

In contrast, low-quality LMX relationships “are characterized by less support, more formal supervision, little or no involvement in decisions, and less trust and attention from the leader.”17 Ultimately, many positive outcomes happen for a follower who enters into a high LMX relationship with a leader. Before looking at some positive outcomes from high LMX relationships, we’re first going to examine the stages involved in the creation of these relationships.

Stages of LMX Relationships

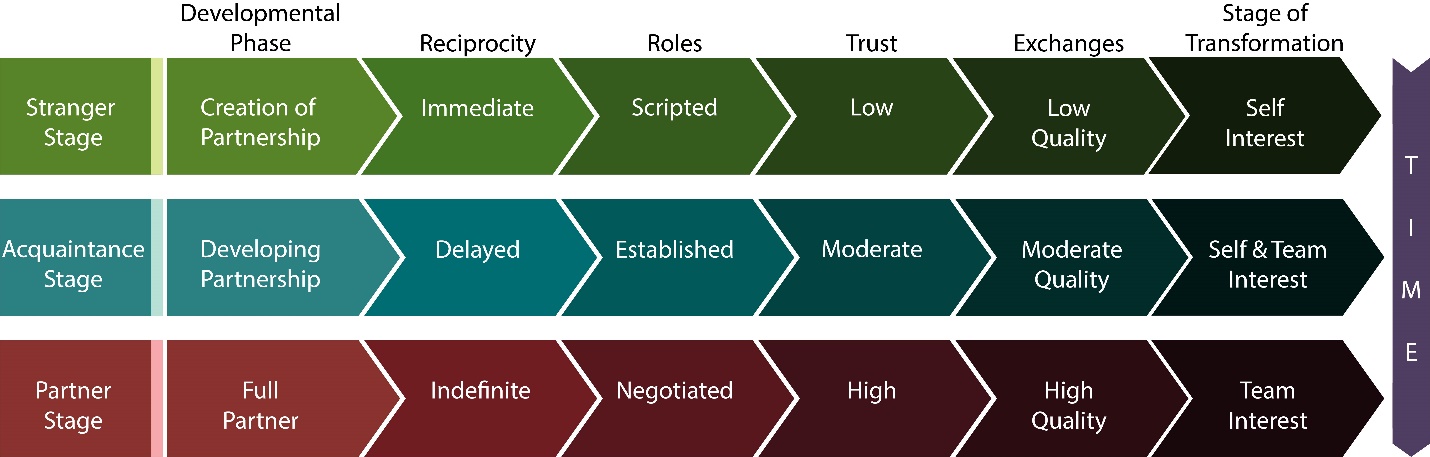

So, you may be wondering how LMX relationships are developed. George B. Graen and Mary Uhl-Bien18 created a three-stage model for the development of LMX relationships. Figure 13.3 represents the three different stages discussed by Graen and Uhl-Bien: stranger, acquaintance, and partner.

Stranger Stage

The first stage of LMX relationships is the stranger stage, and this is the beginning of the creation of an LMX relationship. Most LMX relationships never venture beyond the stranger stage because of the resources needed on both the side of the follower and the leader to progress further.

As you can see from Figure 13.3, the stranger stage is one where their self-interests primarily guide the follower and the leader. These exchanges generally involve what Graen and Uhl-Bien call a “cash and carry” relationship. Cash and carry refers to the idea that some stores don’t utilize credit, so all purchases are made in cash, and customers carry their purchased goods right then. In the stranger stage, interactions between a follower and leader follow this same process. The leader helps the follower and gets something immediately in return. Low levels of trust mark these relationships, and interactions tend to be carried out through scripted forms of communication within the normal hierarchical structure of the organization.

Acquaintance Stage

The second stage of high-quality LMX relationships is the acquaintance stage or exchanges between a leader and follower become more normalized and aren’t necessarily based on a cash and carry system. According to Graen and Uhl-Bien, “Leaders and followers may begin to share greater information and resources, on both a personal and work level. These exchanges are still limited, however, and constitute a ‘testing’ stage—with the equitable return of favors within a limited time perspective.”19 At this point, neither the leader nor the follower expects to get anything immediately in return within the exchange relationship. Instead, they start seeing this relationship as something that has the potential for long-term benefits for both sides. There also is a switch from purely personal self-interests to a combination of both self-interests and the interests of one’s team or organization.

Partner Stage

The final stage in the development of LMX relationships is the partner stage or the stage where a follower stops being perceived as a follower and starts being perceived as an equal or colleague. A level of maturity marks these relationships. Even though the two people within the exchange relationship may still have titles of leader and follower, there is a sense of equality between the individuals within the relationship.

Outcomes of High LMX Relationships

Ultimately, high LMX relationships take time to develop, and most people will not enter into a high LMX relationship within their lifetime. These are special relationships but can have a wildly powerful impact on someone’s career and life. The following are some of the known outcomes of high LMX relationships when compared to those in low LMX relationships:

- Increased productivity (both quality and quantity).

- Increased job satisfaction.

- Less likely to quit.

- Increased supervisor satisfaction.

- Increased organizational commitment.

- Increased satisfaction with the communication practices of the team and organization.

- Increased clarity about one’s role in the organization.

- Increased likelihood to go beyond their job duties to help other employees.

- Higher levels of success in their careers.

- Increased likelihood of providing honest feedback.

- Increased motivation at work.

- Higher levels of influence within their organization.

- Receive more desirable work assignments.

- Higher levels of attention and support from organizational leaders.

- Increased organizational participation. 20, 21, 22, 23

Research Spotlight

In a 2019 article, Leah Omilion-Hodges, Scott Shank, and Christine Packard wanted to find out what young adults want in a manager. To start, the researchers orally interviewed 22 undergraduate students (mean age was 22). They asked the students about the general desires they have for managers, which included questions about general management style and communication (frequency and quality). Previous research by Omilon-Hodges and Christine Sugg had determined five management archetypes, which was reaffirmed in the current study:24

- Mentor: An empathetic advocate, professional, and personal guide.

- Manager: A proxy for organizational leadership who takes a transactional approach to leader-follower relationships.

- Teacher: Seen as a traditional educator who provides role testing episodes, clear feedback, and opportunities for redemption and growth.

- Friend: Although in a managerial position, perceived as an informed and approachable peer.

- Gatekeeper: A high-status actor who is positioned to either advocate for or against an employee. 25

In the current set of focus group interviews, the researchers focused more on the communicative and relational behaviors students wanted out of managers:

- Mentor: Role model, leads by example, makes and leaves an impact, advocate, and life coach.

- Manager: The nuts and bolts of a functional organization, lack of personal relationship, monitor and delegate tasks, maintain the establishment, structured and organized, stick to the plan, follow rules and regulations, strictly business, rules, hierarchy, protocol, and proficient.

- Teacher: Dedicated, provide learning opportunities, supportive, dedicated to growth of the organization, information delegation, provides necessary resources, provides explicit directions and feedback, one-on-one instruction.

- Friend: Well-developed relationship outside of work, empathetic; support in all areas of your life, similarity, identity development, values employees as whole people, relationally focused.

- Gatekeeper: Removed from day-to-day operations, strategic, can help you advance or hold you back, rules and regulation abiding, restricts information at their discretion, communicates only to influence, controls the successes and or failures of followers. 26

With the focus groups completed, the researchers used what they learned to create a 54-item measure of management archetypes, which they then tested with a sample of 153 participants. During the analysis process, the researchers lost the gatekeeper set of questions, but the other four management archetypes held firm. This study was confirmed in a third study using 249 students.

Omilion-Hodges, L. M., Shank, S. E., & Packard, C. M. (2019). What young adults want: A multistudy examination of vocational anticipatory socialization through the lens of students’ desired managerial communication behaviors. Management Communication Quarterly, 33(4), 512–547. https://doi.org/10.1177/0893318919851177

Followership

Although there is a great deal of leadership about the concepts of leadership, there isn’t as much about people who follow those leaders. Followership is “the act or condition under which an individual helps or supports a leader in the accomplishment of organizational goals.”27

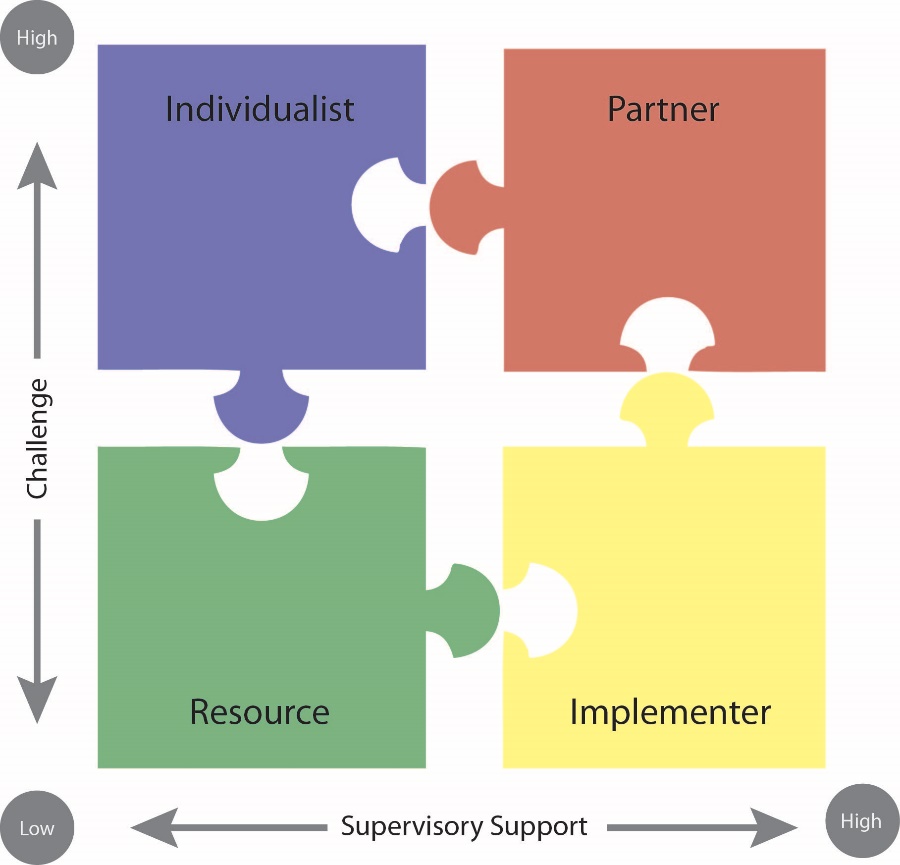

Ira Chaleff (http://www.courageousfollower.net/) was one of the first researchers to examine the nature of followership in his book, The Courageous Follower.28 Chaleff believes that followership is not something that happens naturally for a lot of people, so it is something that people must be willing to engage in. From this perspective, followership is not a passive behavior. Ultimately, followership can be broken down into two primary factors: the courage to support the leader and the courage to challenge the leader’s behavior and policies. Figure 13.4 represents the general breakdown of Chaleff’s four types of followers: resource, individualist, implementer, and partner. Before proceeding, you may want to watch the video Chaleff produced that uses tango to illustrate his basic ideas of followership (https://youtu.be/Cswrnc1dggg).

Resource

The first follower style discussed by Chaleff is the resource. Resources will not challenge or support their leader. Chaleff argues that resources generally lack the intellect, imagination, and courage to do more than what is asked of them. When it comes to resources, they usually do what is requested of them, but nothing that goes beyond that.

Individualist

The second followership style is the individualist. Individualists tend to do what they think is best in the organization, not necessarily what they’ve been asked to do. It’s not that individualists are inherently bad followers; they have their perspectives on how things should get accomplished and are more likely to follow their perspectives than those of their leaders. Individualists provide little support for their leaders, and they are the first to speak out with new ideas that contradict their leader’s ideas.

Implementer

The third followership style is the implementer. Implementers are very important for organizations because they tend to do the bulk of the day-to-day work that needs to be accomplished. Implementers busy themselves performing tasks and getting things done, but they do not question or challenge their leaders.

Partner

The final type of followership is the partner. Partners have an inherent need to be seen as equal to their leaders with regard to both intellect and skill levels. Partners take responsibility for their own and their leader’s ideas and behaviors. Partners do support their leaders but have no problem challenging their leaders. When they do disagree with their leaders, partners point out specific concerns with their leader’s ideas and behaviors.

Key Takeaways

- Hersey and Blanchard’s situational-leadership theory can be seen in Figure 13.2. As part of this theory, Hersey and Blanchard noted four different types of leaders: directing, coaching, supporting, and delegating. Directing leaders set the basic roles an individual has and the tasks an individual needs to accomplish. Coaching leaders still set the basic roles and tasks that need to be accomplished by specific followers, but they allow for input from their followers. Supporting leader allows followers to make the day-to-day decisions related to getting tasks accomplished, but determining what tasks need to be accomplished is a mutually agreed upon decision. And a delegating leader is one where the follower and leader are mutually involved in the basic decision making and problem-solving process, but the ultimate control for accomplishing tasks is left up to the follower.

- Leader-member exchange theory (LMX) explores how leaders enter into two-way relationships with followers through a series of exchange agreements enabling followers to grow or be held back. There are three stages of LMX relationships: strange, acquaintance, and partner. The stranger stage is one where their self-interests primarily guide the follower and the leader. Next, the acquaintance stage involves exchanges between a leader and follower become more normalized and aren’t necessarily based on a cash and carry system. Finally, the partner stage is when a follower stops being perceived as a follower and starts being perceived as an equal or colleague.

- Followership is the act or condition under which an individual helps or supports a leader in the accomplishment of organizational goals. In Ira Chaleff’s concept of followership, he describes for different followership styles: resource, individualist, implementer, and partner. First, a resource is someone who will not support nor challenge their leader. Second, an individualist is someone who engages in low levels of supervisory support but high levels of challenge for a leader. Third, implementers support their leaders but don’t challenge them, but they are known for doing the bulk of the day-to-day work. Lastly, partners are people who show both high levels of support and challenge for their leaders. Partners have an inherent need to be seen as equal to their leaders with regard to both intellect and skill levels.

Exercises

- Think back to one of your most recent leaders. If you were to compare their leadership style to Hersey and Blanchard’s situational-leadership theory, which of the four leadership styles did this leader use with you? Why do you think this leader used this specific style with you? Did this leader use different leadership styles with different followers?

- Why do you think high LMX relationships are so valuable to one’s career trajectory? Why do you think more followers or leaders go out of their ways to develop high LMX relationships?

- When thinking about your relationship with a recent leader, what type of follower were you according to Ira Chaleff’s concept of followership? Why?

13.3 Coworker (Peer Relationships)

Learning Objectives

- List and explain Patricia Sias’ characteristics of coworker relationships and Jessica Methot’s three additional characteristics.

- Differentiate among Kathy Kram and Lynn Isabella’s three types of coworker relationships.

- Explain Patricia Sias and Daniel Cahill’s list of influencing factors on coworker relationships.

- Describe the three ways coworkers go about disengaging from workplace relationships articulated by Patricia Sias and Tarra Perry.

Characteristics of Coworker Relationships

According to organizational workplace relationship expert Patricia Sias, peer coworker relationships exist between individuals who exist at the same level within an organizational hierarchy and have no formal authority over each other.29 According to Sias, we engage in these coworker relationships because they provide us with mentoring, information, power, and support. Let’s look at all four of these.

Sias’ Reasons for Workplace Relationships

Mentoring

First, our coworker relationships are a great source for mentoring within any organizational environment. It’s always good to have that person who is a peer that you can run to when you have a question or need advice. Because this person has no direct authority over you, you can informally interact with this person without fear of reproach if these relationships are healthy. We’ll discuss what happens when you have nonhealthy relationships in the next section.

Sources of Information

Second, we use our peer coworker relationships as sources for information. One of our coauthors worked in a medical school for a while. Our coauthor quickly realized that there were some people he could talk to around the hospital who would gladly let our coauthor know everything that was going on around the place. One important caveat to all of this involves the quality of the information we are receiving. By information quality, Sias refers to the degree to which an individual perceives the information they are receiving as accurate, timely, and useful. Ever had that one friend who always has great news, that everyone else heard the previous week? Yeah, not all information sources provide you with quality information. As such, we need to establish a network of high-quality information sources if we are going to be successful within an organizational environment.

Issues of Power

Third, we engage in coworker relationships as an issue of power. Although two coworkers may exist in the same run within an organizational hierarchy, it’s important also to realize that there are informal sources of power as well. In the next chapter, we are going to explore the importance of power within interpersonal relationships in general. For now, we’ll say that power can be useful and helps us influence what goes on within our immediate environments. However, power can also be used to control and intimidate people, which is a huge problem in many organizations.

Social Support

The fourth reason we engage in peer coworker relationships is social support. For our purposes, let’s define social support as the perception and actuality that an individual receives assistance, care, and help from those people within their life. Let’s face it; there’s a reason corporate America has been referred to as the concrete jungle, circuses, or theatres of the absurd. Even the best organization in the world can be trying at times. The best boss in the world will eventually get under your skin about something. We’re humans; we’re flawed. As such, no organization is perfect, so it’s always important to have those peer coworkers we can go to who are there for us. One of our coauthors has a coworker our coauthor calls whenever our coauthor needs to be “talked off the ledge.” Our coauthor likes higher education and loves being a professor, but occasionally something happens, and our coauthor needs the coworker to vent to about something that has occurred. For the most part, our coauthor doesn’t want the coworker to solve a problem; our coauthor just wants someone to listen as our coauthor vents. We all need to de-stress in the workplace, and having peer coworker relationships is one way we do this.

Other Characteristics

In addition to the four characteristics discussed by Sias, Jessica Methot30 argued that three other features are also important: trust, relational maintenance, and ability to focus.

Trust

Methot defines trust as “the willingness to be vulnerable to another party with the expectation that the other party will behave with the best interest of the focal individual.”31 In essence, in the workplace, we eventually learn how to make ourselves vulnerable to our coworkers believing that our coworkers will do what’s in our best interests. Now, trust is an interesting and problematic concept because it’s both a function of workplace relationships but also an outcome. For coworker relationships to work or operate as they should, we need to be able to trust our coworkers. However, the more we get to know our coworkers and know they have our best interests at heart, then the more we will ultimately trust our coworkers. Trust develops over time and is not something that is not just a bipolar concept of trust or doesn’t trust. Instead, there are various degrees of trust in the workplace. At first, you may trust your coworkers just enough to tell them surface level things about yourself (e.g., where you went to college, major, hometown, etc.), but over time, as we’ve discussed before in this book, we start to self-disclose as deeper levels as our trust increases. Now, most coworker relationships will never be intimate relationships or even actual friendships, but we can learn to trust our coworkers within the confines of our jobs.

Relational Maintenance

Kathryn Dindia and Daniel J. Canary wrote that definitions of the term “relational maintenance” could be broken down into four basic types:

- To keep a relationship in existence;

- To keep a relationship in a specified state or condition;

- To keep a relationship in a satisfactory condition; and

- To keep a relationship in repair.32

Mithas argues that relational maintenance is a difficult task in any context. Still, coworker relationships can have a range of negative outcomes if organizational members have difficulty maintaining their relationships with each other. For this reason, Mithas defines maintenance difficulty as “the degree of difficulty individuals experience in interpersonal relationships due to misunderstandings, incompatibility of goals, and the time and effort necessary to cope with disagreements.”33 Imagine you have two coworkers who tend to behave in an inappropriate fashion nonverbally. Maybe he sits there and rolls his eyes at everything his coworker says, or perhaps she uses exaggerated facial expressions to mock her coworker when he’s talking. Having these types of coworkers will cause us (as a third party witnessing these problems) to spend more time trying to maintain relationships with both of them. On the flip side, the relationship between our two coworkers will take even more maintenance to get them to a point where they can just be collegial in the same room with each other. The more time we have to spend trying to decrease tension or resolve interpersonal conflicts in the workplace, the less time we will ultimately have on our actual jobs. Eventually, this can leave you feeling exhausted feeling and emotionally drained as though you just don’t have anything else to give. When this happens, we call this having inadequate resources to meet work demands. All of us will eventually hit a wall when it comes to our psychological and emotional resources. When we do hit that wall, our ability to perform job tasks will decrease. As such, it’s essential that we strive to maintain healthy relationships with our coworkers ourselves, but foster an environment that encourages our coworkers to maintain healthy relationships with each other. However, it’s important to note that some people will simply never play well in the sandbox others. Some coworker relationships can become so toxic that minimizing contact and interaction can be the best solution to avoid draining your psychological and emotional resources.

Ability to Focus

Have you ever found your mind wandering while you are trying to work? One of the most important things when it comes to getting our work done is having the ability to focus. Within an organizational context, Methot defines “ability to focus” as “the ability to pay attention to value-producing activities without being concerned with extraneous issues such as off-task thoughts or distractions.”34 When individuals have healthy relationships with their coworkers, they are more easily able to focus their attention on the work at hand. On the other hand, if your coworkers always play politics, stabbing each other in the back, gossiping, and engaging in numerous other counterproductive workplace (or deviant workplace) behaviors, then it’s going to be a lot harder for you to focus on your job.

Types of Coworker Relationships

Now that we’ve looked at some of the characteristics of coworker relationships, let’s talk about the three different types of coworkers research has categorized. Kathy Kram and Lynn Isabella35 found that there are essentially three different types of coworker relationships in the workplace: information peer, collegial peer, and special peer. Figure 13.5 illustrates the basic things we get from each of these different types of peer relationships.

Information Peers

Information peers are so-called because we rely on these individuals for information about job tasks and the organization itself. As you can see from Figure 13.5, there are four basic types of activities we engage information peers for information sharing, workplace socialization/onboarding, networking, and knowledge management/maintenance.

Information Sharing

First, we share information with our information peers. Of course, this information is task-focused, so the information is designed to help us complete our job better.

Workplace Socialization and Onboarding

Second, information peers are vital during workplace socialization or onboarding. Workplace socialization can be defined as the process by which new organizational members learn the rules (e.g., explicit policies, explicit procedures, etc.), norms (e.g., when you go on break, how to act at work, who to eat with, who not to eat with, etc.), and culture (e.g., innovation, risk-taking, team orientation, competitiveness, etc.) of an organization. Organizations often have a very formal process for workplace socialization that is called onboarding. Onboarding is when an organization helps new members get acquainted with the organization, its members, its customers, and its products/services.

Networking

Third, information peers help us network within our organization or a larger field. Half of being successful in any organization involves getting to know the key players within the organization. Our information peers will already have existing relationships with these key players, so they can help make introductions. Furthermore, some of our peers may connect with others in the field (outside the organization), so they could help you meet other professionals as well.

Knowledge Management/Maintenance

Lastly, information peers help us manage and maintain knowledge. During the early parts of workplace socialization, our information peers will help us weed through all of the noise and focus on the knowledge that is important for us to do our jobs. As we become more involved in an organization, we can still use these information peers to help us acquire new knowledge or update existing knowledge. When we talk about knowledge, we generally talk about two different types: explicit and tacit. Explicit knowledge is information that is kept in some retrievable format. For example, you’ll need to find previously written reports or a list of customers’ names and addresses. These are examples of the types of information that physically (or electronically) may exist within the organization. Tacit knowledge, on the other hand, is the knowledge that’s difficult to capture permanently (e.g., write down, visualize, or permanently transfer from one person to another) because it’s garnered from personal experience and contexts. Informational peers who have been in an organization for a long time will have a lot of tacit knowledge. They may have an unwritten history of why policies and procedures are the way they are now, or they may know how to “read” certain clients because they’ve spent decades building relationships. For obvious reasons, it’s much easier to pass on explicit knowledge than implicit knowledge.

Collegial Peers

The second class of relationships we’ll have in the workplace are collegial peers or relationships that have moderate levels of trust and self-disclosure and is different from information peers because of the more openness that is shared between two individuals. Collegial peers may not be your best friends, but they are people that you enjoy working with. Some of the hallmarks of collegial peers include career strategizing, job-related feedback, recognizing competence/performance, friendship.

Career Strategizing

First, collegial peers help us with career strategizing. Career strategizing is the process of creating a plan of action for one’s career path and trajectory. First, notice that career strategizing is a process, so it’s marked by gradual changes that help you lead to your ultimate result. Career strategizing isn’t something that happens once, and we stay on that path for the rest of our lives. Often or intended career paths take twists and turns we never expected nor predicted. However, our collegial peers are often great resources for helping us think through this process either within a specific organization or a larger field.

Job-Related Feedback

Second, collegial peers also provide us with job-related feedback. We often turn to those who are around us the most often to see how we are doing within an organization. Our collegial peers can provide us this necessary feedback to ensure we are doing our jobs to the utmost of our abilities and the expectations of the organization. Under this category, the focus is purely on how we are doing our jobs and how we can do our jobs better.

Recognizing Competence/Performance

Third, collegial peers are usually the first to recognize our competence in the workplace and recognize us for excellent performance. Generally speaking, our peers have more interactions with us on the day-to-day job than does middle or upper management, so they are often in the best position to recognize our competence in the workplace. Our competence in the workplace can involve having valued attitudes (e.g., liking hard work, having a positive attitude, working in a team, etc.), cognitive abilities (e.g., information about a field, technical knowledge, industry-specific knowledge, etc.), and skills (e.g., writing, speaking, computer, etc.) necessary to complete critical work-related tasks. Not only do our peers recognize our attitudes, cognitive abilities, and skills, they are also there to pat us on the backs and tell us we’ve done a great job when a task is complete.

Friendship

Lastly, collegial peers provide us a type of friendship in the workplace. They offer us a sense of camaraderie in the workplace. They also offer us someone we can both like and trust in the workplace. Now, it’s important to distinguish this level of friendships from other types of friendships we have in our lives. Collegial peers are not going to be your “best friends,” but they will offer you friendships within the workplace that make work more bearable and enjoyable. At the collegial level, you may not associate with these friends outside of work beyond workplace functions (e.g., sitting next to each other at meetings, having lunch together, finding projects to work on together, etc.). It’s also possible that a group of collegial peers will go to events outside the workplace as a group (e.g., going to happy hour, throwing a holiday party, attending a baseball game, etc.).

Special Peers

The final group of peers we work with are called special peers. Kram and Isabella note that special peer relationships “involves revealing central ambivalences and personal dilemmas in work and family realms. Pretense and formal roles are replaced by greater self-disclosure and self-expression.”36 Special peer relationships are marked by confirmation, emotional support, personal feedback, and friendship.

Confirmation

First, special peers provide us with confirmation. When we are having one of our darkest days at work and are not sure we’re doing our jobs well, our special peers are there to let us know that we’re doing a good job. They approve of who we are and what we do. These are also the first people we go to when we do something well at work.

Emotional Support

Second, special peers provide us with emotional support in the workplace. Emotional support from special peers comes from their willingness to listen and offer helpful advice and encouragement. Kelly Zellars and Pamela Perrewé have noted there are four types of emotional social support we get from peers: positive, negative, non-job-related, and empathic communication.37 Positive emotional support is when you and a special peer talk about the positive sides to work. For example, you and a special peer could talk about the joys of working on a specific project. Negative emotional support, on the other hand, is when you and a special peer talk about the downsides to work. For example, maybe both of you talk about the problems working with a specific manager or coworker. The third form of emotional social support is non-job-related or talking about things that are happening in your personal lives outside of the workplace itself. These could be conversations about friends, family members, hobbies, etc. A good deal of the emotional social support we get from special peers has nothing to do with the workplace at all. The final type of emotional social support is empathic communication or conversations about one’s emotions or emotional state in the workplace. If you’re having a bad day, you can go to your special peer, and they will reassure you about the feelings you are experiencing. Another example is talking to your special peer after having a bad interaction with a customer that ended with the customer yelling at you for no reason. After the interaction, you seek out your special peer, and they will confirm your feelings and thoughts about the interaction.

Personal Feedback

Third, special peers will provide both reliable and candid feedback about you and your work performance. One of the nice things about building an intimate special peer relationship is that both of you will be honest with one another. There are times we need confirmation, but then there are times we need someone to be bluntly honest with us. We are more likely to feel criticized and hurt when blunt honesty comes from someone when we do not have a special peer relationship. Special peer relationships provide a safe space where we can openly listen to feedback even if we’re not thrilled to receive that feedback.

Friendship

Lastly, special peers also offer us a sense of deeper friendship in the workplace. You can almost think of special peers as your best friend(s) within the workplace. Most people will only have one or maybe two people they consider a special peer in the workplace. You may be friendly with a lot of your peers (i.g., collegial peers), but having that special peer relationship is deeper and more meaningful.

A Further Look at Workplace Friendships

At some point, a peer coworker relationship may, or may not, evolve into a workplace friendship. According to Patricia Sias, there are two key hallmarks of a workplace friendship: voluntariness and personalistic focus. First, workplace friendships are voluntary. Someone can assign you a mentor or a mentee, but that person cannot make you form a friendship with that person. Most of the people you work with will not be your friends. You can have amazing working relationships with your coworkers, but you may only develop a small handful of workplace friendships. Second, workplace friendships have a personalistic focus. Instead of just viewing this individual as a coworker, we see this person as someone who is a whole individual who is a friend. According to research, workplace friendships are marked by higher levels of intimacy, frankness, and depth than those who are peer coworkers.38

Friendship Development in the Workplace

According to Patricia Sias and Daniel Cahill, workplace friendships are developed by a series of influencing factors: individual/personal factors, contextual factors, and communication changes. 39 First, some friendships develop because we are drawn to the other person. Maybe you’re drawn to a person in a meeting because she has a sense of humor that is similar to yours, or maybe you find that another coworker’s attitude towards the organization is exactly like yours. Whatever the reason we have, we are often drawn to people that are like us. For this reason, we are often drawn to people who resemble ourselves demographically (e.g., age, sex, race, religion, etc.).

A second reason we develop relationships in the workplace is because of a variety of different contextual factors. Maybe your office is right next to someone else’s office, so you develop a friendship because you’re next to each other all the time. Perhaps you develop friendships because you’re on the same committee or put on the same work project with another person. In large organizations, we often end up making friends with people simply because we get to meet them. Depending on the size of your organization, you may end up meeting and interact with a tiny percentage of people, so you’re not likely to become friends with everyone in the organization equally. Other organizations provide a culture where friendships are approved of and valued. In the realm of workplace friendship research, two important factors have been noticed concerning contextual factors controlled by the organization: opportunity and prevalence.40 Friendship opportunity refers to the degree to which an organization promotes and enables workers to develop friendships within the organization. Does your organization have regular social gatherings for employees? Does your organization promote informal interaction among employees, or does it clamp down on coworker communication? Not surprisingly, individuals who work in organizations that allow for and help friendships tend to be satisfied, more motivated, and generally more committed to the organization itself.

Friendship prevalence, on the other hand, is less of an organizational culture and more the degree to which an individual feels that they have developed or can develop workplace friendships. You may have an organization that attempts to create an environment where people can make friends, but if you don’t think you can trust your coworkers, you’re not very likely to make workplace friends. Although the opportunity is important when seeing how an individual responds to the organization, friendship prevalence is probably the more important factor of the two. If I’m a highly communicative apprehensive employee, I may not end up making any friends at work, so I may see my workplace place as just a job without any commitment at all. When an individual isn’t committed to the workplace, they will probably start looking for another job.41

Lastly, as friendships develop, our communication patterns within those relationships change. For example, when we move from being just an acquaintance to being a friend with a coworker, we are more likely to increase the amount of communication about non-work and personal topics. When we transition from friend to close friend, Sias and Cahill note that this change is marked by decreased caution and increased intimacy. Furthermore, this transition in friendship is characterized by an increase in discussing work-related problems. The final transition from a close friend to “almost best” friend. According to Sias and Cahill, “Because of the increasing amount of trust developed between the coworkers, they felt freer to share opinions and feelings, particularly their feelings about work frustrations. Their discussion about both work and personal issues became increasingly more detailed and intimate.”42

Relationship Disengagement

Thus far, we’ve talked about workplace friendships as positive factors in the workplace, but any friendship can sour. Some friendships sour because one person moves into a position of authority of the other, so there is no longer perceived equality within the relationship. Other friendships occur when there is a relationship violation of some kind (see Chapter 8). Some friendships devolve because of conflicting expectations of the relationship. Maybe one friend believes that giving him a heads up about insider information in the workplace is part of being a friend, and the other person sees it as a violation of trust given to her by her supervisors. When we have these conflicting ideas about what it means to “be a friend,” we can often see a schism that gets created. So, how does an individual get out of workplace friendships? Patricia Sias and Tarra Perry were the first researchers to discuss how colleagues disengage from relationships with their coworkers.43 Sias and Perry found three distinct tools that coworkers use: state-of-the-relationship talk, cost escalation, and depersonalization. Before explaining them, we should mention that people use all three and do not necessarily progress through the three in any order.

State-of-the-Relationship Talk

The first strategy people use when disengaging from workplace friendships involves state-of-the-relationship talk. State-of-the-relationship talk is exactly what it sounds like; you officially have a discussion that the friendship is ending. The goal of state-of-the-relationship talk is to engage the other person and inform them that ending the friendship is the best way to ensure that the two can continue a professional, functional relationship. Ideally, all workplace friendships could end in a situation where both parties agree that it’s in everyone’s best interest for the friendship to stop. Still, we all know this isn’t always the case, which is why the other two are often necessary.

Cost Escalation

The second strategy people use when ending a workplace friendship involves cost escalation. Cost escalation involves tactics that are designed to make the cost of maintaining the relationship higher than getting out of the relationship. For example, a coworker could start belittling a friend in public, making the friend the center of all jokes, or talking about the friend behind the friend’s back. All of these behaviors are designed to make the cost of the relationship too high for the other person.

Depersonalization

The final strategy involves depersonalization. Depersonalization can come in one of two basic forms. First, an individual can depersonalization a relationship by stopping all the interaction that is not task-focused. When you have to interact with the workplace friend, you keep the conversation purely business and do not allow for talk related to personal lives. The goal of this type of behavior is to alter the relationship from one of closeness to one of professional distance. The second way people can depersonalize a relationship is simply to avoid that person. If you know a workplace friend is going to be at a staff party, you purposefully don’t go. If you see the workplace friend coming down the hallway, you go in the opposite direction or duck inside a room before they can see you. Again, the purpose of this type of depersonalization is to put actual distance between you and the other person. According to Sias and Perry’s research, depersonalization tends to be the most commonly used tactic.44

Key Takeaways

- According to Patricia Sias, people engage in workplace relationships for several reasons: mentoring, information, power, and support. Jessica Methot’s further suggested that we engage in coworker relationships for trust, relational maintenance, and the ability to focus.

- Kathy Kram and Lynn Isabella explained that there are three different types of workplace relationships: information peer, collegial peer, and special peer. Information peers are coworkers we rely on for information about job tasks and the organization itself. Collegial peers are coworkers with whom we have moderate levels of trust and self-disclosure and more openness that is shared between two individuals. Special peers, on the other hand, are coworkers marked by high levels of trust and self-disclosure, like a “best friend” in the workplace.

- Patricia Sias and Daniel Cahill’s created a list of influencing factors on coworker relationships. First, some coworkers we are simply more drawn to than others. As such, traditional notions of interpersonal attraction and homophily are at play. A second influencing factor involves contextual changes. Often there are specific contextual changes (e.g., moving offices, friendship opportunity, and friendship prevalence) impact the degree to which people develop coworker friendships. Finally, communication changes as we progress through the four types of coworker friendships: acquaintance, friend, close friend, and almost best friend.

- Patricia Sias and Tarra Perry describe three different ways that coworkers can disengage from coworker relationships in the workplace. First, individuals can engage in state-of-the-relationship talk with a coworker, or explain to a coworker that a workplace friendship is ending. Second, individuals can make the cost of maintaining the relationship higher than getting out of the relationship, which is called cost escalation. The final disengagement strategy coworkers can utilize, depersonalization occurs when an individual stops all the interaction with a coworker that is not task-focused or simply to avoids the coworker.

Exercises

- Think about your workplace relationships with coworkers. Which of Patricia Sias’ four reasons and Jessica Methot’s three additional characteristics were at play in these coworker relationships?

- Kathy Kram and Lynn Isabella described three different types of peers we have in the workplace: information peer, collegial peer, and special peer. Think about your workplace. Can you identify people who fall into all three categories? If not, why do you think you don’t have all three types of peers? If you do, how are these relationships distinctly different from one another?

- Think about an experience where you needed to end a workplace relationship with a coworker. Which of Patricia Sias and Tarra Perry’s disengagement strategies did you use? Do you think there are other disengagement strategies available beyond the ones described by Sias and Perry?

13.4 Romantic Relationships at Work

Learning Objectives

- Define the term “romantic workplace relationship.”

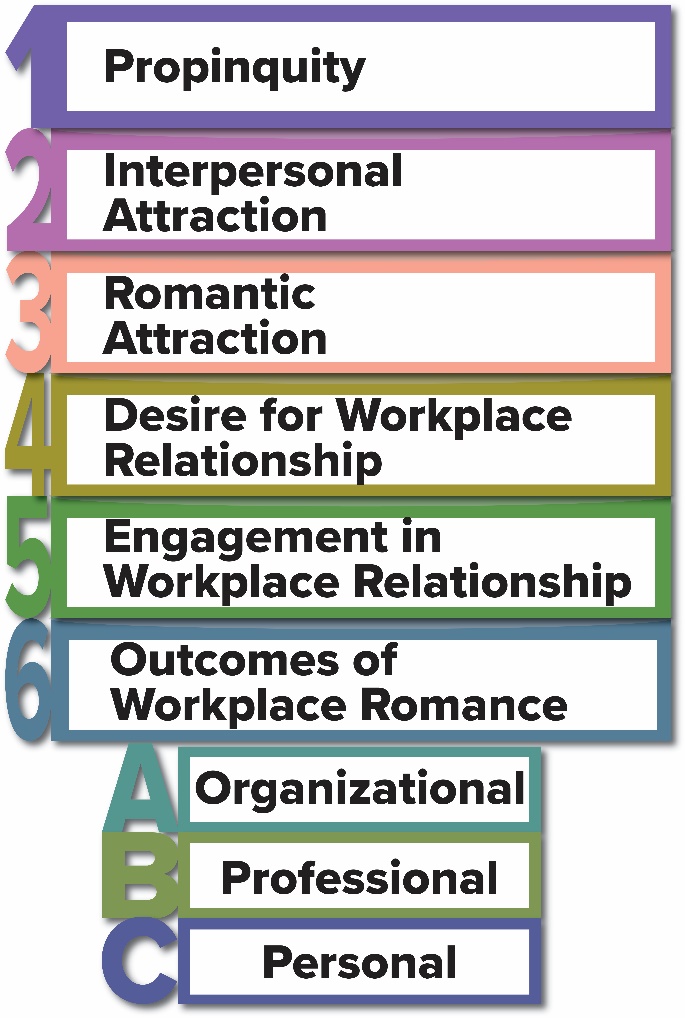

- Reconstruct Charles Pierce, Donn Byrne, and Herman Aguinis’ model of romantic workplace relationships.

- Describe the four reasons why romantic workplace relationships develop discovered by Renee Cowan and Sean Horan.

- Summarize the findings related to how coworkers view romantic workplace relationships.