Chapter 8: Building and Maintaining Relationships

Over the course of our lives, we will enter into and out of many different relationships. When it comes to dating, the average person has seven relationships before getting married.1 According to a study conducted by OnePoll in conjunction with Evite, the average American has:

- Three best friends

- Five good friends

- Eight people they like but don’t spend one-on-one time with

- 50 acquaintances

- 91 social media friends2

In this chapter, we are going to discuss how we go about building and maintaining our interpersonal relationships.

8.1 The Nature of Relationships

Learning Objectives

- Understand relationship characteristics.

- Identify the purposes of relationships.

- Cognize the elements of a good relationship.

We’ve all been in a wide range of relationships in our lives. This section is going to explore relationships by examining specific relationship characteristics and the nature of significant relationships.

Relationship Characteristics

We all know that all relationships are not the same. We have people in our lives that we enjoy spending time with, like to support us, and/or assist us when needed. We will typically distance ourselves from people who do not provide positive feelings or outcomes for us. Thus, all there are many characteristics in relationships that we have with others. These characteristics are: duration, contact frequency, sharing, support, interaction variability, and goals.3

Some friendships last a lifetime, others last a short period. The length of any relationship is referred to as that relationship’s duration. People who grew up in small towns might have had the same classmate till graduation. This is due to the fact that duration with each person is different. Some people we meet in college and we will never see them again. Hence, our duration with that person is short. Duration is related to the length of your relationship with that person.

Second, contact frequency is how often you communicate with their other person. There are people in our lives we have known for years but only talk to infrequently. The more we communicate with others, the closer our bond becomes to the other person. Sometimes people think duration is the real test of a relationship, but it also depends on how often you communicate with the other person.

The third relationship type is based on sharing. The more we spend time with other people and interact with them, the more we are likely to share information about ourselves. This type of sharing is information that is usually our private and very intimate details of our thoughts and feelings. We typically don’t share this information with a stranger. Once we develop a sense of trust and support with this person, we can begin to share more details.

The fourth characteristic is support. Think of the people in your life and who you would be able to call in case of an emergency. The ones that come to mind are the ones you know who would be supportive of you. They would support you if you needed help, money, time, or advice. Support is another relationship type because we know that not everyone can support us in the same manner. For instance, if you need relationship advice, you would probably pick someone who has relationship knowledge and would support you in your decision. Support is so important. It was found that a major difference between married and dating couples is that married couples were more likely to provide supportive communication behaviors to their partners more than dating couples.4

The fifth defining characteristic of relationships is the interaction variability. When we have a relationship with another person, it is not defined on your interaction with them, rather on the different types of conversations you can have with that person. When you were little, you probably knew that if you were to approach your mom, she might respond a certain way as opposed to your day, who might respond differently. Hence, you knew that your interaction would vary. The same thing happens with your classmates because you don’t just talk about class with them. You might talk about other events on campus or social events. Therefore, our interactions with others are defined by the greater variability that we have with one person as opposed to another.

The last relationship characteristic is goals. In every relationship we enter into, we have certain expectations about that relationship. For instance, if your goal is to get closer to another person through communication, you might share your thoughts and feelings and expect the other person to do the same. If they do not, then you will probably feel like the goals in your relationship were not met because they didn’t share information. The same goes for other types of relationships. We typically expect that our significant other will be truthful, supportive, and faithful. If they break that goal, then it causes problems in the relationship and could end the relationship. Hence, in all our relationships, we have goals and expectations about how the relationship will function and operate.

Significant Relationships

Think about all the relationships that you have in your life. Which ones are the most meaningful and significant for you? Why do you consider these relationships as the most notable one(s) for you? Your parents/guardians, teachers, friends, family members, and love interests can all serve as significant relationships for you. Significant relationships have a huge impact on our communication behaviors and our interpretation of these conversations. Significant relationships impact who we are and help us grow. These relationships can serve a variety of purposes in our lives.

Purposes of Relationships

Relationships can serve a variety of purposes: work, task, and social. First, relationships can be work-related. We might have a significant work relationship that helps us advance our professional career. We might have work relationships that might support us in gaining financial benefits or better work opportunities. Second, we might have significant relationships because it is task-related. We may have a specific task that we need to accomplish with this other person. It might be a project or a mentorship. After the task is completed, then the relationship may end. For instance, a high school coach may serve as a significant relationship. You and your coach might have a task or plan to go to the state competition. You and your coach will work on ways to help you. However, after you complete high school and your task has ended, then you might keep in contact with the coach, or you may not since your competition (task) has ended. The last purpose is for social reasons. We may have social reasons for pursuing a relationship. These can include pleasure, inclusion, control, and/or affection. Each relationship that we have with another person has a specific purpose. We may like to spend time with a particular friend because we love talking to them. At the same time, we might like spending time with another friend because we know that they can help us become more involved with extracurricular activities.

Elements of a Good Relationship

In summary, relationships are meaningful and beneficial. Relationships allow us to grow psychologically, emotionally, and physically. We can connect with others and truly communicate. The satisfaction of our relationships usually determines our happiness and health.

Key Takeaways

- The nature of a relationship is not determined immediately; often, it evolves and is defined and redefined over time.

- Relationship characteristics include duration, contact frequency, sharing, support, interaction variability, and goals. The purposes of a relationship are for security and health.

- Elements of a good relationship include trust, commitment, willingness to work together to maintain the relationship, support, intimacy, empathy, and skills for dealing with emotions.

Exercises

- Conduct an inventory of your relationships. Think of all the people in your life and how they meet each of the relationship characteristics.

- Write a list of all the good relationships that you have with others or witnessed. What makes these relationships good? Is it similar to what we talked about in this chapter? Was anything different? Why?

- Write a hypothetical relationship article for a website. What elements make a lasting relationship? What would you write? What would you emphasize? Why? Let a friend read it and provide input.

8.2 Relationship Formation

Learning Objectives

- Understand attraction.

- Ascertain reasons for attraction.

- Realize the different types of attraction.

Have you ever wondered why people pick certain relationships over others? We can’t pick our family members, although I know someone people wish they could. We can, however, select who are friends and significant others are in our lives. Throughout our lives, we pick and select people that we build a connection to and have an attraction towards. We tend to avoid certain people who we don’t find attractive.

Understanding Attraction

Researchers have identified three primary types of attraction: physical, social, and task. Physical attraction refers to the degree to which you find another person aesthetically pleasing. What is deemed aesthetically pleasing can alter greatly from one culture to the next. We also know that pop culture can greatly define what is considered to be physically appealing from one era to the next. Think of the curvaceous ideal of Marilyn Monroe and Elizabeth Taylor in the 1950s as compared to the thin Halley Barry or Anne Hathaway. Although discussions of male physical attraction occur less often, they are equally impacted by pop culture. In the 1950s, you had solid men like Robert Mitchum and Marlon Brando as compared to the heavily muscled men of today like Joe Manganiello or Zac Efron.

The second type of attraction is social attraction, or the degree to which an individual sees another person as entertaining, intriguing, and fun to be around. We all have finite sources when it comes to the amount of time we have in a given day. We prefer to socialize with people that we think are fun. These people may entertain us or they may just fascinate us. No matter the reason, we find some people more socially desirable than others. Social attraction can also be a factor of power. For example, in situations where there are kids in the “in-group” and those that are not. In this case, those that are considered popular hold more power and are perceived as being more socially desirable to associate with. This relationship becomes problematic when these individuals decide to use this social desirability as a tool or weapon against others.

The final type of attraction is task attraction, or people we are attracted to because they possess specific knowledge and/or skills that help us accomplish specific goals. The first part of this definition requires that the target of task attraction possess specific knowledge and/or skills. Maybe you have a friend who is good with computers who will always fix your computer when something goes wrong. Maybe you have a friend who is good in math and can tutor you. Of course, the purpose of these relationships is to help you accomplish your own goals. In the first case, you have the goal of not having a broken down computer. In the second case, you have the goal of passing math. This is not to say that an individual may only be viewed as task attractive, but many relationships we form are because of task attraction in our lives.

Reasons for Attraction

Now that we’ve looked at the basics of what attraction is. Let’s switch gears and talk about why we are attracted to each other. There are several reasons researchers have found for our attraction to others including proximity, physicality, perceived gain, similarities and differences, and disclosure.

Physical Proximity

When you ask some people how they met their significant other, you will often hear proximity is a factor in how they met. Perhaps, they were taking the same class or their families went to the same grocery store. These commonplaces create opportunities for others to meet and mingle. We are more likely to talk to people that we see frequently.

Physical Attractiveness

In day-to-day interactions, you are more likely to pay attention to someone you find more attractive than others. Research shows that males place more emphasis on physical attractiveness than females.5 Appearance is very important at the beginning of the relationship.

Perceived Gain

This type of relationship might appear to be like an economic model and can be explained by exchange theory.6 In other words, we will form relationships with people who can offer us rewards that outweigh the costs. Rewards are the things we want to acquire. They could be tangible (e.g., food, money, clothes) or intangible (support, admiration, status). Costs are undesirable things that we don’t want to expend a lot of energy to do. For instance, we don’t want to have to constantly nag the other person to call us or spend a lot of time arguing about past items. A good relationship will have fewer costs and more rewards. A bad relationship will have more costs and fewer rewards. Often, when people decide to stay or leave a relationship, they will consider the costs and rewards in the relationship.

Costs and rewards are not the only factors in a relationship. Partners also consider alternatives in the relationship. For instance, Becky and Alan have been together for a few years. Becky adores Alan and wants to marry him, but she feels that there are some problems in the relationship. Alan has a horrible temper; he is pessimistic; and he is critical of her. Becky has gained some weight, and Alan has said some hurtful things to her. Becky knows that every relationship will have issues. She doesn’t know whether to continue this relationship and take it further or if she should end it.

Her first alternative is called the comparison level(CL), which is the minimum standard that she is willing to tolerate. If Becky believes that it is ok for a person to say hurtful things to her or get angry, then Alan is meeting or exceeding her CL. However, if past romantic partners have never said anything hurtful towards her, then she would have a lower CL.

Becky will also consider another alternative, which is the comparison level of alternatives (CLalt), or the comparison between current relationship rewards and what she might get in another relationship. If she doesn’t want to be single, then she might have a lower CL of alternatives. If she has another potential mate who would probably treat her better, then she would have a higher level of alternatives. We use this calculation all the time in relationships. Often when people are considering the possibility to end a relationship, they will consider all alternatives rather than just focusing on costs and rewards.

Similarities and Differences

It feels comforting when someone who appears to like the same things you like also has other similarities to you. Thus, you don’t have to explain yourself or give reasons for doing things a certain way. People with similar cultural, ethnic, or religious backgrounds are typically drawn to each other for this reason. It is also known as similarity thesis. The similarity thesis basically states that we are attracted to and tend to form relationships with others who are similar to us.7 There are three reasons why similarity thesis works: validation, predictability, and affiliation. First, it is validating to know that someone likes the same things that we do. It confirms and endorses what we believe. In turn, it increases support and affection. Second, when we are similar to another person, we can make predictions about what they will like and not like. We can make better estimations and expectations about what the person will do and how they will behave. The third reason is due to the fact that we like others that are similar to us and thus they should like us because we are the same. Hence, it creates affiliation or connection with that other person.

However, there are some people who are attracted to someone completely opposite from who they are. This is where differences come into play. Differences can make a relationship stronger, especially when you have a relationship that is complementary. In complementary relationships, each person in the relationship can help satisfy the other person’s needs. For instance, one person likes to talk, and the other person likes to listen. They get along great because they can be comfortable in their communication behaviors and roles. In addition, they don’t have to argue over who will need to talk. Another example might be that one person likes to cook, and the other person likes to eat. This is a great relationship because both people are getting what they like to do, and it complements each other’s talents. Usually, friction will occur when there are differences of opinion or control issues. For example, if you have someone who loves to spend money and the other person who loves to save money, it might be very hard to decide how to handle financial issues.

Disclosure

Sometimes we form relationships we others after we have disclosed something about ourselves to others. Disclosure increases liking because it creates support and trust between you and this other person. We typically don’t disclose our most intimate thoughts to a stranger. We do this behavior with people we are close to because it creates a bond with the other person.

Disclosure is not the only factor that can lead to forming relationships. Disclosure needs to be appropriate and reciprocal.8 In other words, if you provide information, it must be mutual. If you reveal too much or too little, it might be regarded as inappropriate and can create tension. Also, if you disclose information too soon or too quickly in the relationship, it can create some negative outcomes.

Key Takeaways

- We can be attracted to another person via various ways. It might be due to physical proximity, physical appearance, perceived gain, similarity/differences, and disclosure.

- The deepening of relationships can occur through disclosure and mutual trust.

- Relationships end through some form of separation or dissolution.

Exercises

- Take a poll of the couples that you know and how they met. Which category does it fall into? Is there a difference among your couples and how they met?

- What are some ways that you could form a relationship with others? Discuss your findings with the class. How is it different/similar to what we talked about in this chapter?

- Discuss how and why a certain relationship that you know dissolved. What were the reasons or factors that caused the separation?

8.3 Stages of Relationships

Learning Objectives

- Describe the coming together stages.

- Discern the coming apart stages.

- Realize relationship maintenance strategies.

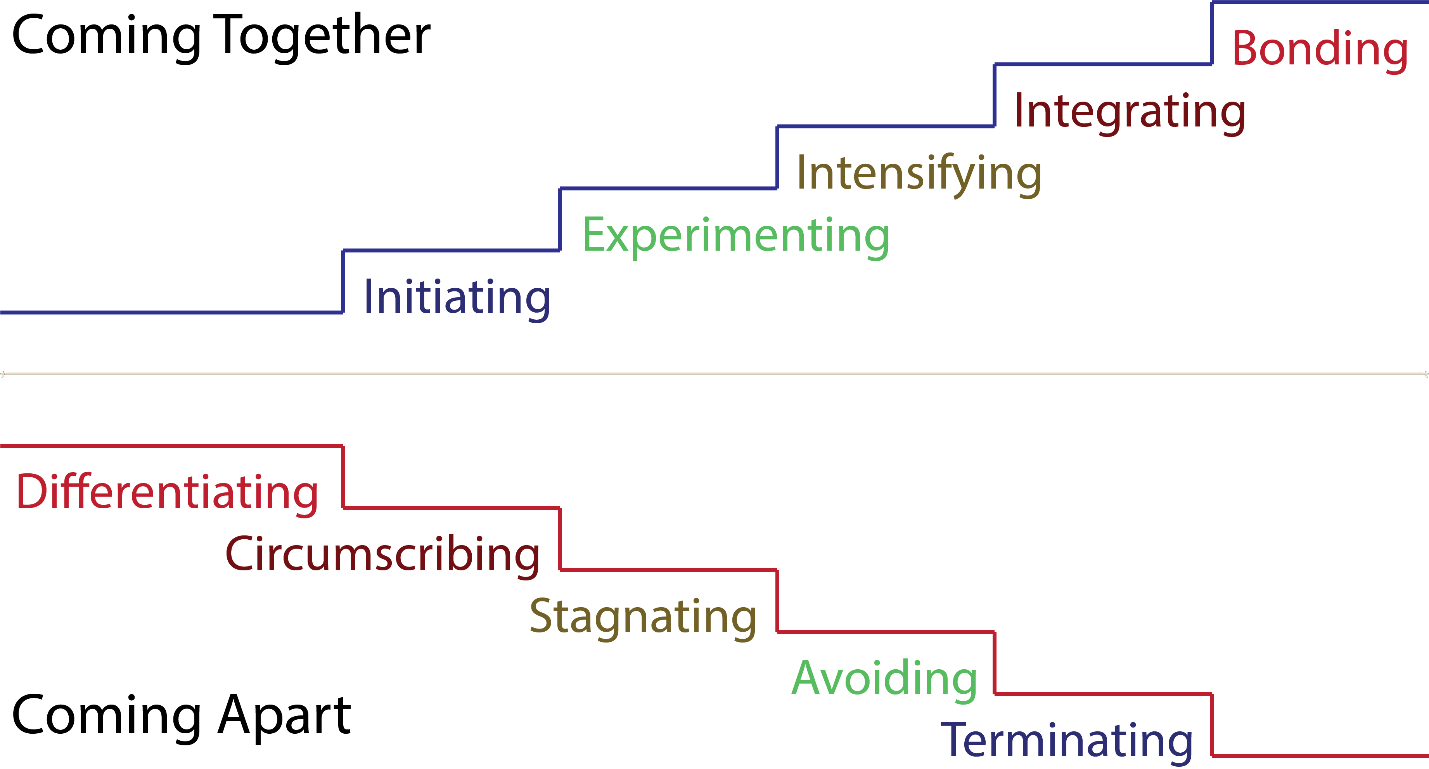

Every relationship does through various stages. Mark Knapp first introduced a series of stages that relationships can progress.9 This model was later modified by himself and coauthor Anita Vangelisti creates a model of relationships.10 They believe that we come together and we can come apart in stages. Relationships can get stronger or weaker. Most relationships go through some or all of these stages.

Coming Together

Do you remember when you first met that special someone in your life? How did your relationship start? How did you two become closer? Every relationship has to start somewhere. It begins and grows. In this section, we will learn about the coming together stages, which include: initiating, experimenting, intensifying, integrating, and then bonding.

Initiating

At the beginning of every relationship, we have to figure out if we want to put in the energy and effort to talk to the other person. If we are interested in pursuing the relationship, we have to let the other person know that we are interested in initiating a conversation.

There are different types of initiation. Sustaining is trying to continue the conversation. Networking is where you contact others for a relationship. An offering is where you present your interest in some manner. Approaching is where you directly make contact with the other person. We can begin a relationship in a variety of different ways.

Communication at this initiating stage is very brief. We might say hello and introduce yourself to the other person. You might smile or wink to let the other person know you are interested in making conversation with him or her. The conversation is very superficial and not very personal at all. At this stage, we are primarily interested in making contact.

Experimenting

After we have initiated communication with the other person, we go to the next stage, which is experimenting. At this stage, you are trying to figure out if you want to continue the relationship further. We are trying to learn more about the other person.

At this stage, interactions are very casual. You are looking for common ground or similarities that you share. You might talk about your favorite things, such as colors, sports, teachers, etc. Just like the name of the stage, we are experimenting and trying to figure out if we should move towards the next stage or not.

Intensifying

After we talk with the other person and decide that this is someone we want to have a relationship with, we enter the intensifying stage. We share more intimate and/or personal information about ourselves with that person. Conversations become more serious, and our interactions are more meaningful. At this stage, you might stop saying “I” and say “we.” So, in the past, you might have said to your partner, “I am having a night out with my friends.” It changes to “we are going to with my friends tonight.” We are becoming more serious about the relationship.

Integrating

The integrating stage is where two people truly become a couple. Before they might have been dating or enjoying each other’s company, but in this stage, they are letting people know that they are exclusively dating each other. The expectations in the relationship are higher than they were before. Your knowledge of your partner has increased. The amount of time that you spend with each other is greater.

Bonding

The next stage is the bonding stage, where you reveal to the world that your relationship to each other now exists. It might be as simple as a Facebook post. For others, the bonding stage is where they get engaged and have an engagement announcement. For those that are very committed to the relationship, they might decide to have a wedding and get married. In every case, they are making their relationship a public announcement. They want others to know that their relationship is real.

Coming Apart

Some couples can stay in committed and wonderful relationships. However, there are some couples that after bonding, things seem to fall apart. No matter how hard they try to stay together, there is tension and disagreement. These couples go through a coming apart process that involves: differentiating, circumscribing, stagnating, avoiding, and terminating.

Differentiating

The differentiating stage is where both people are trying to figure out their own identities. Thus, instead of trying to say “we,” the partners will question “how am I different?” In this stage, differences are emphasized and similarities are overlooked.

As the partners differentiate themselves from each other, they tend to engage in more disagreements. The couples will tend to change their pronoun use from “our kitchen” becomes “my kitchen” or “our child” becomes “my child,” depending on what they want to emphasize.

Initially, in the relationship, we tend to focus on what we have in common with each other. After we have bonded, we are trying to deal with balancing our independence from the other person. If this cannot be resolved, then tensions will emerge, and it usually signals that your relationship is coming apart.

Circumscribing

The circumscribing stage is where the partners tend to limit their interactions with each other. Communication will lessen in quality and quantity. Partners try to figure out what they can and can’t talk about with each other so that they will not argue.

Partners might not spend as much time with each other at this stage. There are fewer physical displays of affection, as well. Intimacy decreases between the partners. The partners no longer desire to be with each other and only communicate when they have to.

Stagnating

The next stage is stagnating, which means the relationship is not improving or growing. The relationship is motionless or stagnating. Partners do not try to communicate with each other. When communication does occur, it is usually restrained and often awkward. The partners live with each other physically but not emotionally. They tend to distance themselves from the other person. Their enthusiasm for the relationship is gone. What used to be fun and exciting for the couple is now a chore.

Avoiding

The avoiding stage is where both people avoid each other altogether. They would rather stay away from each other than communicate. At this stage, the partners do not want to see each other or speak to each other. Sometimes, the partners will think that they don’t want to be in the relationship any longer.

Terminating

The terminating stage is where the parties decide to end or terminate the relationship. It is never easy to end a relationship. A variety of factors can determine whether to cease or continue the relationship. Time is a factor. Couples have to decide to end it gradually or quickly. Couples also have to determine what happens after the termination of the relationship. Besides, partners have to choose how they want to end the relationship. For instance, some people end the relationship via electronic means (e.g., text message, email, Facebook posting) or via face-to-face.

Final Thoughts on Coming Together

Not every relationship will go through each of the ten stages. Several relationships do not go past the experimenting stage. Some remain happy at the intensifying or bonding stage. When both people agree that their relationship is satisfying and each person has their needs met, then stabilization occurs. Some relationships go out of order as well. For instance, in some arranged marriages, the bonding occurs first, and then the couple goes through various phases. Some people jump from one stage into another. When partners disagree about what is optimal stabilization, then disagreements and tensions will occur.

In today’s world, romantic relationships can take on a variety of different meanings and expectations. For instance, “hooking up” or having “friends with benefits” are terms that people might use to describe the status of their relationship. Many people might engage in a variety of relationships but not necessarily get married. We know that relationships vary from couple to couple. No matter what the relationship type, couples decided to come together or come apart.

Relationship Maintenance

You may have heard that relationships are hard work. Relationships need maintenance and care. Just like your body needs food and your car needs gasoline to run, your relationships need attention as well. When people are in a relationship with each other, what makes a difference to keep people together is how they feel when they are with each other. Maintenance can make a relationship more satisfying and successful.

Daniel Canary and Laura Stafford stated that “most people desire long-term, stable, and satisfying relationships.”11 To keep a satisfying relationship, individuals must utilize relationship maintenance behaviors. They believed that if individuals do not maintain their relationships, the relationships will weaken and/or end. “It is naïve to assume that relationships simply stay together until they fall apart or that they happen to stay together.”12

Joe Ayres studied how individuals maintain their interpersonal relationships.13 Through factor analysis, he identified three types of strategies. First, avoidance strategies are used to evade communication that might threaten the relationship. Second, balance strategies are used to maintain equality in the relationship so that partners do not feel underbenefited or overbenefited from being in the relationship. Third, direct strategies are used to evaluate and remind the partner of relationship objectives. It is worth noting that Joe Ayers found that relationship intent had a major influence on the perceptions of the relationship partners. If partners wanted to stay together, they would make more of an effort to employ maintenance strategies than deterioration strategies.

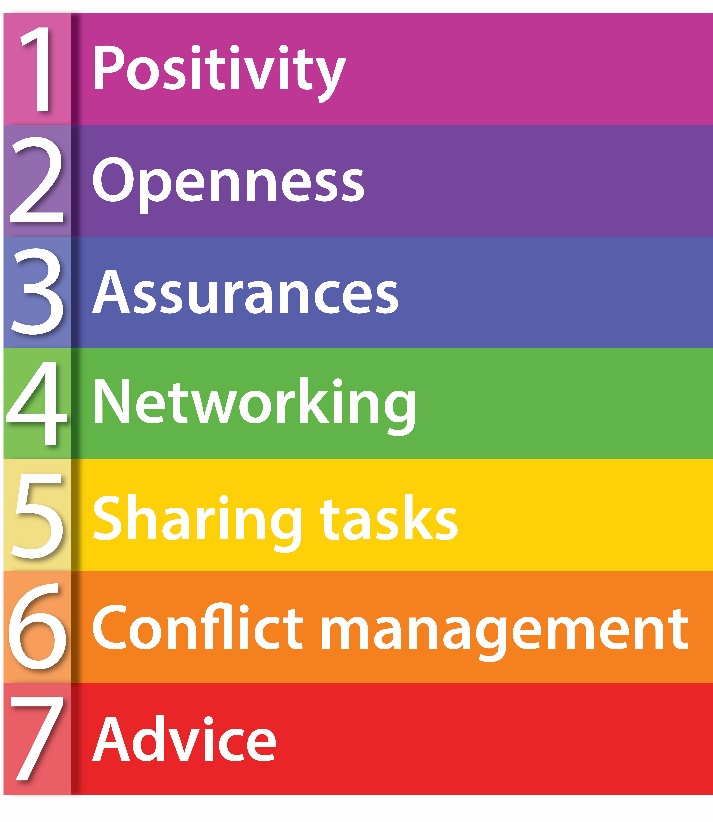

Laura Stafford and Daniel Canary (1991) found five key relationship maintenance behaviors. First, positivity is a relational maintenance factor used by communicating with their partners in a happy and supportive manner. Second, openness occurs when partners focus their communication on the relationship. Third, assurances are words that emphasize the partners’ commitment to the duration of the relationship. Fourth, networking is communicating with family and friends. Lastly, sharing tasks is doing work or household tasks. Later, Canary and his colleagues found two more relationship maintenance behaviors: conflict management and advice.14

Additionally, Canary and Stafford also posited four propositions that serve as a conceptual framework for relationship maintenance research.15 The first proposition is that relationships will worsen if they are not maintained. The second proposition is that both partners must feel that there are equal benefits and sacrifices in the relationship for it to sustain. The third proposition states that maintenance behaviors depend on the type of relationship. The fourth proposition is that relationship maintenance behaviors can be used alone or as a mixture to affect perceptions of the relationship. Overall, these propositions illustrate the importance and effect that relationship maintenance behaviors can have on relationships.

Relationship maintenance is the stabilization point between relationship initiation and potential relationship destruction.16 There are two elements to relationship maintenance. First, strategic plans are intentional behaviors and actions used to maintain the relationship. Second, everyday interactions help to sustain the relationship. Most importantly, talk is the most important element in relationship maintenance.17

Mindfulness Activity

Learning how to use mindfulness in our interpersonal relationships is one way to ensure healthy relationships. Lauren Korshak recommends using the RAIN method when interacting with one’s relational partners:

- Recognize: Nonjudgmentally recognize and name emotions you feel in the present moment.

- Allow: Acknowledge, accept, and allow your emotions to be as they are without trying to change them. Allowing does not mean you like what is happening, but that you allow it, dislike and all.

- Investigate with kindness: Ask yourself, “What am I experiencing inside my body? What is calling my attention? What does this feeling need from me?”

- Non-identification/nurture with self-compassion: Observe thoughts, feelings, and sensations without attaching to them. If you notice painful feelings, nurture them by placing a hand over your heart or speaking words of kindness, reassurance, and compassion, such as “I see you’re suffering,” or “I’m sorry,” or “I love you, I’m listening.”18

For this activity, we want you to use the RAIN method in a conversation with your romantic partner. As an alternative variant, both of you can engage in the RAIN method and discuss a recent conflict you had. The goal is not to establish fault or a win-lose attitude, but rather to learn to empathize with your partner and their perspective.

Key Takeaways

- The coming together stages include: initiating, experimenting, intensifying, integrating, and bonding.

- The coming apart stages include: differentiating, circumscribing, stagnating, avoiding, and terminating.

- Relationship maintenance strategies include positivity, openness, assurances, sharing tasks, conflict management, social networks, and advice.

Exercises

- Find Internet clips that illustrate each of the coming together/coming apart stages. Show them to your class. Do you agree/disagree?

- Do a self-analysis of a relationship that you have been involved with or have witnessed. How did the two people come together and come apart? Did they go through all the stages? Why/why not?

- Write down an example of each the relationship maintenance strategies. Then, rank order in terms of importance to you. Why did you rank them the way that you did? Find a peer and compare your answers.

8.4 Communication in Relationships

Learning Objectives

- Learn how communication varies.

- Analyze relationship dialectics.

- Understand self-disclosure in relationships.

Relationship Dialectics

We know that all relationships go through change. The changes in a relationship are usually dependent on communication. When a relationship starts, there is lots of positive and ample communication between the parties. However, there are times that couples go through a redundant problem, and it is important to learn how to deal with this problem. Partners can’t always know what their significant other desires or needs from them.

Dialectics had been a concept known well too many scholars for many years. They are simply the pushes and pulls that can be found every day in relationships of all types. Conversation involves people who must learn to adapt to each other while still maintaining their individuality.19 The theory emphasizes interactions allowing for more flexibility to explain how couples maintain a satisfactory, cohesive union. This perspective views relationships as simply managing the tensions that arise because they cannot be fully resolved. The management of the tensions is usually based on past experiences; what worked for a person in the past will be what they decide to use in the future. These tensions are both contradictory and interdependent because without one, the other is not understood. Leslie A. Baxter, the scholar who developed this theory, pulled from as many outside sources as she could to better understand the phenomenon of dialectical tensions within relationships. The development began by closely studying the works of Mikhail Bakhtin, who was a Russian scholar of culture, literature, philosophy, and language. Baxter was interested in his life’s work; the theory often was referred to as dialogism. Bakhtin argued that life is a social process of dialogue that is characterized by the concurrent coming together and separating of individual perspectives.

Early in Baxter’s career, she noticed that while she was interested in the termination of relationships, her colleagues were interested in the beginnings. Although her colleagues were interested in disclosure, she was interested in non-disclosure. At this point, it still had not occurred to her that these opposing interests in research would lead her to the understanding of dialectical tensions. She continued to research these subjects and read as much as she could on Marxist and Hegelian dialectics as she found these writings to be both fascinating and frustrating. She processed these writings slowly, and the concepts slowly began to show up in her work. In 1993, Baxter and Montgomery began writing a book on dialectics called Relating: Dialogues and Dialectics. This was her first official work done on dialectics and its conversational effects. She continued writing about dialectics and continued to expand the concepts as she further researched families, romantic relationships, and friendships. Since then, Baxter has continually changed and shifted her studies to find new and better ways to use the theory. After conducting a series of in-depth interviews, both Baxter and Montgomery began to see themes in the tensions experienced in romantic relationships. Their overarching research premise (which is applicable to all relationships—including mother/daughter relationships) is that all personal ties and relationships are always in a state of constant flux and contradiction. Relational dialectics highlight a “dynamic knot of contradictions in personal relationships; an unceasing interplay between contrary or opposing tendencies.”20 The concept of contradiction is crucial to understanding relational dialectics. The contradiction is when there are opposing sides to a situation. These contradictions tend to arise when both parties are considered interdependent. Dialectical tension is natural and inevitable All relationships are complex because human beings are complex, and this fact is reflected in our communicative processes. Baxter and Montgomery argue that tension arises because we are drawn to the antitheses of opposing sides. These contradictions must be met with a “both/and” approach as opposed to the “either/or” mindset. However, the “both/and” approach lends to tension and pressure, which almost always guarantees that relationships are not easy.

Dialectical tension is how individuals deal with struggles in their relationship. There are opposing forces or struggles that couples have to deal with. It is based on Leslie Baxter and Barbara Montgomery’s Relational Dialectics Theory in 1996. Below are some different relational dialectics.21

Separation-Integration

This is where partners seek involvement but not willing to sacrifice their entire identity. For instance, in a marriage, some women struggle with taking their partner’s last name, keeping their maiden name, or combine the two. Often when partners were single, they might have engaged in a girl’s night out or a guy’s night out. When in a committed relationship, one partner might feel left out and want to be more involved. Thus, struggles and conflict occur until the couple can figure out a way to deal with this issue.

Predictability–Novelty

This deals with rituals/routines compared to novelty. For instance, for some mothers, it is tough to accept that their child is an adult. They want their child to grow up at the same time it is difficult to recognize how their child has grown up.

Openness–Closedness

Disclosure is necessary, but there is a need for privacy. For some couples, diaries work to keep things private. Yet, there are times when their partner needs to know what can’t be expressed directly through words.

Similarity-Difference

This tension deals with self vs. others. Some couples are very similar in their thinking and beliefs. This is good because it makes communication easier and conflict resolution smoother. Yet, if partners are too similar, then they cannot grow. Differences can help couples mature and create stimulation.

Ideal-Real

Couples will perceive some things as good and some things as bad. Their perceptions of what is real may interfere or inhibit perceptions of what is real. For instance, a couple may think that their relationship is perfect. But from an outsider, they might think that the relationship is abusive and devastating.

Another example might be that a young dating couple thinks that they do not have to marry each other because it is the ideal and accepted view of taking the relationship to the next phase. Thus, the couples move in together and raise a family without being married. They have deviated from what is an ideal normative cultural script.22

Every relationship is fraught with these dialectical tensions. There’s no way around them. However, there are different ways of managing dialectical tensions:

- Denial is where we respond to one end.

- Disorientation is where we feel overwhelmed. We fight, freeze, or leave.

- Alternation is where we choose one end on different occasions.

- Recalibration is reframing the situation or perspective.

- Segmentation is where we compartmentalize different areas.

- Balance is where we manage and compromise our needs.

- Integration is blending different perspectives.

- Reaffirmation is having the knowledge & accepting our differences.

Not every couple deals with dialectical tensions in the same way. Some will use a certain strategy during specific situations, and others will use the same strategy every time there is tension. You have to decide what is best for you based on the situation.

Self-Disclosure

In Chapter 7, we started our discussion of self-disclosure. We discussed Sidney Jourard’s basic definition of self-disclosure, “the act of making yourself manifest, showing yourself so others can perceive you.”23 Jourard believed that self-disclosure was necessary to have good mental health. All and all, Jourard took a very humanistic or health approach to self-disclosure because he deemed that it was an essential and integral part of our wellbeing.

Individuals disclose for a variety of reasons. Sandra Petronio has presented five potential reasons for self-disclosure: (a) expression, (b) self-clarification, (c) social value, (d) relationship development, and (e) social control and influence.24 Petronio extended that, “for each type of disclosure, there is a corresponding expectation communicated that influences the choice of response.”25

Four considerations are pertinent to disclosure.26 First, the type of relationship will affect individuals’ need to disclose. The more significant the disclose is to the disclosure, then the greater the need more to disclose information. Second, the disclosure has a risk-to-benefits ratio. In other words, individuals, who disclose certain types of information, may risk losing certain things (i.e., career or pride) or may benefit certain things (i.e., trust or security). Third, the appropriateness and relevance to the situation impacts what gets disclosed and what does not get disclosed. Fourth, disclosure depends on reciprocity. Individuals will disclose similar amounts of information to each other.

The amount of disclosure that we are willing to share with others also depends on other factors. It is based on honesty, depth, availability of information, and the environment.

First, when we disclose to others, we can truly reveal characteristics about ourselves, or we can lie. In a recent study, it was found that most college students lie when initially meeting someone new for the first time. The cause is because we want to impress others. A lot of deception occurs on online chatrooms because sometimes people do not want to reveal who they really are, because of possible repercussions.

Depth is another factor of self-disclosure. When I talk to my parents, I can share hours of information about my day with them. I can talk about all sorts of things with them. However, I have a friend who is only willing to talk about the weather and what he ate with his parents. As you can see, the depth of information is very different. One person only talks about superficial facts, and the other person delves a lot deeper and is willing to discuss more themselves.

The availability of information has an impact as well. For instance, if you have more information on a certain topic, you might be willing to share more comments on the matter. For instance, if you and your friends are trying to decide which presidential candidate to vote support in the next election. You might be more willing to self-disclose what you know about a candidate and your opinions about that candidate based on your information. However, you might be less willing to comment on another candidate if you don’t know their platform or background.

The context or environment has an impact on self-disclosure. For instance, have you ever noticed that people tend to open up about themselves when they are in a confined space, such as an airplane? It is so interesting to meet how people are willing to share personal information about themselves with a total stranger only because the other person is doing it as well.

Alternatives to Self-Disclosure

So, if you don’t want to self-disclose to others, what are some techniques that you can use? First, you can use deception. Sometimes, people lie simply to avoid conflict. This is true in cases where the person may become extremely upset. They can lie to gain power or to save face. They can also lie to guide the interaction.

Second, you can equivocate. This means you don’t answer the question or provide your comments. Rather, you simply restated what they said differently. For instance, Sally says, “how do you like my new dress?”, you can say “Wow! That’s a new outfit!” In this case, you don’t provide how you feel, and you don’t disclose your opinion. You only offer the information that has been provided to you.

Third, you can hint. Perhaps, you don’t want to lie or equivocate to someone you care about. You might use indirect or face-saving comments. For example, if your roommate has not helped you clean your apartment, you might say things like, “It sure is messy in here?” or “This place could really use some cleaning.”

Key Takeaways

- Communication is personalized. It can be symmetrical or complementary. Communication has two levels – content and relational.

- Relationship dialectics are tensions that happen in a relationship. Partners have to deal with integration vs. separation, stability vs change, and expression vs. privacy.

- Self-disclosure is important in relationships because it allows you to share more information about yourself with another person.

Exercises

- Find a transcript of your favorite television sitcom on the Internet. See if you can identify which types of communication is relational/content and which are symmetrical/complementary.

- Consider three different issues that you might be dealing in a relationship that you have with another person. What are the relationship dialectic tensions? How are you handling these tensions? Identify what strategy you are using to deal with this tension. Why?

- Create a list of all the reasons you would disclose and why you would not disclose. Discuss the finding in class. Were there differences or similarities?

8.5 Dating Relationships

Learning Objectives

- Learn how communication varies.

- Analyze relationship dialectics.

- Understand self-disclosure in relationships.

We talk of dating as a single construct a lot of the time without really thinking through how dating has changed over time. In the twentieth century alone, we saw dating go from a highly formalized structure involving calling cards and sitting rooms; to drive-in movies in the back seat of a car; to cyberdating with people we’ve never met.27 The 21st Century has already changed how people date through social networking sites and geolocation dating apps on smartphones. Dating is not a single thing, and dating has definitely changed with the times.

So, with all of this change, how does one even begin to know if someone’s on a date in the first place. Thankfully Paul Mongeau, Janet Jacobsen, and Carolyn Donnerstein have attempted to answer this question for us.28 The researchers found that there are five what they called “supracategories” that help define the term “date”: communication expectations, date goals, date elements, dyadic, and feelings. First, dating involves specific communication expectations. For example, people expect that there will be a certain level of self-disclosure on a date. Furthermore, people expect that their dating partner will be polite, relaxed, and social. Second, dating involves specific date goals, or people on dates have specific goals (e.g., future romantic relationships, reduce uncertainty, have fun, etc.). Third, there are specific date elements. For example, someone has to initiate the date; we get ready for a date, we know when the date has started and stopped, there are activities that constitute the date, etc… Fourth, dates are dyadic, or dating is a couple-based activity. Now, this doesn’t necessarily take into account the idea of “group dates,” but even on a group date there are dyadic couples that are involved in the date itself. Lastly, dates involve feelings. “These feelings range from affection (nonromantic feelings or behaviors), attraction (physical and/or emotional attraction toward the partner), to romantic (dates have romantic overtones).”29

Dating Scripts

All of us are going to spend a portion of our lives in some kind of dating relationship. Whether we are initiating dates, dating, or termination relationships, we spend a great deal of time dating. Match.com publishes an annual study examining singles in the United States (https://www.singlesinamerica.com/). According to data from 2018,30 here are some of the realities of modern single life:

- 55.8% did not go on any first dates, while only 12.6% went on one first date.

- Of those who went on a first date, 20.3% met the person on an online dating site/app while 15.6% met the person through a friend.

- When it comes to being passionately in love, 19.4% have never been in love, 27.3% have been in love once, and 27.7% have been in love twice.

- 25.1% have a “checklist” when it comes to finding a long-term romantic partner.

- 66.7% believe that loving someone is hard work.

- 75.2% believe that love is a possibility for them.

- 83.5% believe that love is hard to find in today’s world.

- 32.4% of dating partners have disagreed on how to label their relationship, and 23.0% have left a relationship over this disagreement.

- When it comes to first dates, participants preferred either quick and easy (36.0%, e.g., coffee, drinks, etc.) or more formal (21%, e.g., dinner, brunch, etc.).

- 38.1% had been a “friends with benefits” relationship.

- 28.3% had a friendship that turned into a significant romantic relationship.

- 41.1% have dated someone they met online.

- 48.9% had created at least one profile on a dating website or app.

Admittedly, this study is probably pretty heterosexist because the data were not broken down by sexual orientation. Furthermore, we don’t have similar data for bisexual, gay, and lesbian couples. Dating is one of those things we will spend a lot of time doing before we ever settle down and get married (assuming you ever do or have a desire to do so). So, one must imagine that with so much dating going on in the world, we’d have a pretty good grasp of how dating works.

Robert Abelson originally proposed the idea of script theory back in the late 1970s.31 He defined a script as a “coherent sequence of events expected by the individual, involving him as either a participant or an observer.”32 According to script theory, people tend to pattern their responses and behaviors during different social interactions to take control of that situation. This does require an individual to be able to imagine their past, present, and future behavior to create this script.33 In 1993, Suzanna Rose and Irene Frieze applied Abelson’s notions of script theory to dating. They had college students keep records of what they did on a date. Ultimately, two different scripts were derived: one for men and one for women. The male script consisted of 15 different behavioral actions (all initiated by the male):34

- Picked up date

- Met parents/roommates

- Left

- Picked up friends

- Confirm plans

- Talked, joked, laughed

- Went to movies, show, party

- Ate

- Drank alcohol

- Initiated sexual contact

- Made out

- Took date home

- Asked for another date

- Kissed goodnight

- Went home

Women’s scripts, on the other hand, contained both behavioral actions for themselves and behavioral actions they expected of the man during the date: 35

- Groomed and dressed

- Was nervous

- Picked up date (male)

- Introduced to parents, etc.

- Courtly behavior (open doors–male)

- Left

- Confirmed plans

- Got to know & evaluate date

- Talked, joked, laughed

- Enjoyed date

- Went to movies, show, party

- Ate

- Drank alcohol

- Talked to friends

- Had something go wrong

- Took date home (male)

- Asked for another date (male)

- Told date will call her (male)

- Kissed date goodnight (male)

Take a second and go through these two lists. Do you think they still apply today? How do you think these scripts differ? Once again, these dating scripts were created only using heterosexual college students. Do you think these scripts change if you have people dating in their late 20s or 30s? What about people who date in their 70s, 80s, or 90s?

There has been subsequent research in the area of dating scripts. Table 8.1 demonstrates some of the other dating scripts that researchers have found (this is not an exhaustive list).

| First Date36 | Gay Men37 | Lesbians38 | Deaf College Students39 |

|---|---|---|---|

| (M) denotes male behavior | |||

|

|

|

|

Table 8.1 Dating Scripts

We often think of dating as something that occurs purely among young people before they get married, but we know people in all age groups date and are looking for romantic relationships of all shapes and sizes.

One other facet of script theory that is very important to consider is how we learn these scripts in the first place. As you read through both the male and female dating script, did you consciously think about how you learned to date? Of course not! However, we’ve been conditioned since we were very young to date. We’ve listened to adults tell stories of dating. We’ve watched dating as it is fictionalized on television and in movies. Dating narratives surround us, and all of these narratives help create the dating scripts that we have. Although dating may feel like you’re making it up as you go along, you already possess a treasure trove of information about how dating works. Thankfully, because we have these cultural images of dating presented to us, we also know that our dating partner (as long as they are from a similar culture) will have similar dating scripts.

Research Spotlight

One area that has received a decent amount of attention in script theory is sexual scripts, or scripts people engage in when thinking about “who can participate, what the participants should do (i.e., what verbal and nonverbal behaviors should be included and in what order they should be used), and where the sexual episode should take place.”40 In 1993, Timothy Edgar and Mary Anne Fitzpatrick proposed a sexual script theory for communication.41 In 2010, this script was further evaluated by Betty La France. In La France’s study, she wanted to examine the verbal and nonverbal communication behaviors that lead to sex. Starting with Edgar and Fitzpatrick’s sexual scripts, La France narrowed the list down to the following:

One area that has received a decent amount of attention in script theory is sexual scripts, or scripts people engage in when thinking about “who can participate, what the participants should do (i.e., what verbal and nonverbal behaviors should be included and in what order they should be used), and where the sexual episode should take place.”40 In 1993, Timothy Edgar and Mary Anne Fitzpatrick proposed a sexual script theory for communication.41 In 2010, this script was further evaluated by Betty La France. In La France’s study, she wanted to examine the verbal and nonverbal communication behaviors that lead to sex. Starting with Edgar and Fitzpatrick’s sexual scripts, La France narrowed the list down to the following:

| Public Setting Script | Private Setting Script (Her Apartment) |

|---|---|

| Craig was standing at the bar when he noticed Sarah. She also noticed him. There was eye contact between them. She glanced away. He approached her. “Hi, my name is Craig,” he said. “I’m Sarah. How are you doing?,” she replied. “Can I buy you a drink?,” he asked. Craig asked, “Are you alone?” “No, I came with some friends,” she replied. Craig asked her questions about herself, such as where she was from and what her major was. She responded to his questions. In return, Sarah asked Craig similar questions about himself. |

She brought him a drink. “Want to listen to some music?,” asked Sarah. She put on the music. Craig asked, “Are your roommates around?” “This is a great apartment,” said Craig. He sat next to her on the couch. They engaged in casual conversation. There was eye contact between them. He moved closer to her. “You are so beautiful,” said Craig. He put his arm around her. Bedroom setting He undressed her. Craig started to undress himself. Sarah helped him to undress. They discussed whether they should use protection. Craig put on a condom. |

As for the results of this study, La France found that people predicted that as the sexual scripts progressed, the likelihood that Sarah and Craig were going to have sexual intercourse increased. Overall, La France found that the sequence of both verbal and nonverbal sexual behaviors could predict the likelihood that people believed that Sarah and Craig would have sex. For example, in the public setting script, when Sarah says, “No, I came with some friends,” this caused people to think that sex could be off-the-table because the statement indicates that the likelihood of the two leaving alone is less likely.

La France, B. (2010). What verbal and nonverbal communication cues lead to sex? An analysis of the traditional sexual script. Communication Quarterly, 58(3), 297–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/01463373.2010.503161

Love Styles

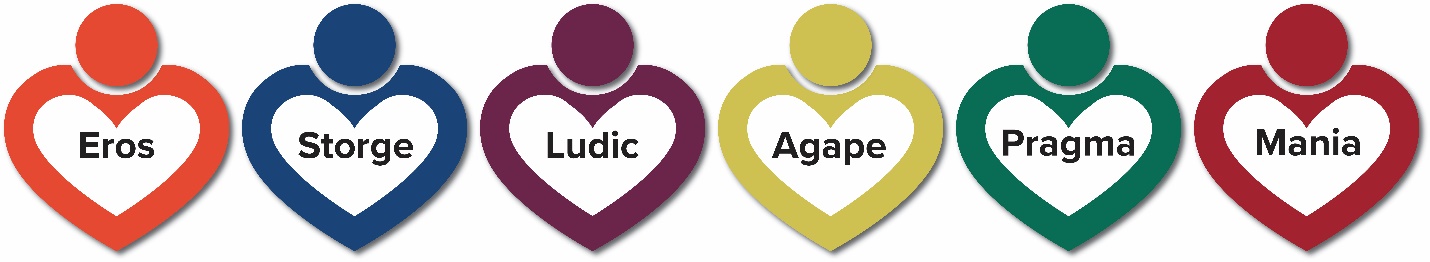

An individual’s love style is considered to be an attitude and describes how love is perceived.42 Attitudes toward love and perceptions of love may change throughout an individual’s life. College students may perceive love very differently from their parents or guardians because college students are in a very different stage of life. College students are living among people their age who are more than likely single or unmarried. These two factors mean that there are more prospects for dating, and this may lead the college student to conclude that dating any number of these prospects is necessary or even perceive that “hooking up” with multiple prospects is acceptable. In contrast, individuals with children who are financially tied may view romantic relationships as partnerships in which goal achievement (pay off the house, send kids to college, pay off debt, etc.) is as important as romance. These differences in perceptions of love can be explored through John Lee’s love typology in which he discusses six love styles: eros, storge, ludus, agape, pragma, and mania (Figure 8.3).43

Eros

Eros is romance and emphasizes love and physical beauty, immediate attraction, emotional intensity, and strong commitment. Eros love involves the early initiation of sexual intimacy and consecutive monogamous relationships.

Storge

Storge love develops slowly out of friendship where stability and psychological closeness are valued along with commitment, which leads to enduring love. Passion and intense emotions are not valued as they are in the eros love style. One of the author’s uncles was in his 60s and had never been married. However, he employed a woman who cooked and cleaned for him for over 20 years. His family was very surprised to receive an announcement that he was marrying the individual who took care of him for so long. The formation of their love is a great example of love that arises slowly out of friendship.

Ludic

Ludic lovers view love as a game, and playing this game with multiple partners is perceived to be acceptable by individuals with this love style. As such, this type of lover believes that deception and manipulation are acceptable. Individuals with this love style have a low tolerance for commitment, jealousy, and strong emotional attachment.

Agape

In contrast, agape love involves altruism, giving, and other-centered love. This love style approaches relationships in a non-demanding style with gentle caring and tolerance for others.

Pragma

Pragma love is known as practical love involving logic and reason. Arranged marriages were often arranged for functional purposes. Kings and Queens of different countries often married to form alliances. This love style may seek out a romantic partner for financial stability, ability to parent, or simple companionship.

Mania

Mania is the final love style characterized by dependence, uncertainty, jealousy, and emotional upheaval. This type of love is insecure and needs constant reassurance.

These love styles should not be considered to be mutually independent. An individual may approach love from a pragmatic stance and have found love that provides financial stability. However, they still feel insecure (representative of mania) about whether their romantic partner will remain with them, thus ensuring continued financial stability. It is important to remember that individuals engage in each of these love styles, and it is simply a matter of how much of each love style a person possesses.

Research Spotlight

In 2015, Alexander Khaddouma, Kristina Coop Gordon, and Jennifer Bolden set out to examine the relationship between mindfulness and relational satisfaction in dating relationships. The researchers predicted that mindfulness would lead to a greater sense of differentiation of self, which would then lead to greater relationship satisfaction. Differentiation of self has two basic components:

In 2015, Alexander Khaddouma, Kristina Coop Gordon, and Jennifer Bolden set out to examine the relationship between mindfulness and relational satisfaction in dating relationships. The researchers predicted that mindfulness would lead to a greater sense of differentiation of self, which would then lead to greater relationship satisfaction. Differentiation of self has two basic components:

On an intrapsychic level, differentiation of self refers to an individual’s ability to distinguish between thoughts and feelings and purposefully choose one’s responses to these thoughts and feelings in present situations.

On an interpersonal level, differentiation of self refers to an individual’s ability to balance intimacy and autonomy in relations with others.44

The concept of differentiation of self stems out of a body of research called family systems theory, which we’ll discuss in more detail in Chapter 11. For now, it’s important to understand that highly differentiated people have healthier levels of persona autonomy in their interpersonal relationships. Conversely, “less differentiated individuals are considered to be more automatically and emotionally reactive in stressful situations and have difficulty maintaining a stable, autonomous sense of self in close relationships.”45

In this study, the researchers found that mindfulness led to greater differentiation of self, which in turn, led to greater overall relationship satisfaction.

Khaddouma, A., Gordon, K. C., & Bolden, J. (2015). Zen and the art of dating: Mindfulness, differentiation of self, and satisfaction in dating relationships. Couple and Family Psychology: Research and Practice, 4(1), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1037/cfp0000035

Key Takeaways

- Romantic relationships involve emotional dependency, fear of separation, and caregiving.

- Romantic love involves attraction to physical beauty.

- The types of love are eros, ludus, mania, storge, pragma, and agape.

- Each love style can be found in all individuals, but some love styles are more prominent than others.

Exercises

- Compare a current or past romantic relationship to the definition of romantic relationships provided in this chapter. What are the similarities and differences in your romantic relationship?

- List the physical features you find attractive. List the personality factors you find attractive. Would you have a romantic relationship with someone who possessed the personality characteristics you find attractive, but not the physical characteristics? Why or why not? Now, consider whether you would have a romantic relationship with someone physically attractive, but did not possess the personality characteristics you find attractive. Would you have a romantic relationship with this individual? Why or why not?

- List and define each love style. List the love style of each of your parents and grandparents. Explain how your love style developed and whether it was learned from a family member or innate.

8.6 How Gender Affects Relationships

Learning Objectives

- Discern the difference between sex and gender.

- Understand the sex and gender differences in communication.

- Discover ways to improve communication.

Biological Sex vs. Gender

Sex refers to one’s biological status as male or female, as determined by chromosomes and secondary sex characteristics. Gender, however, refers to the behaviors and traits society considers masculine and feminine.46 Shuhbra Gaur stated “the meaning of gender, according to her, depends on the ways a culture defines femininity and masculinity which lead to expectations about how individual women and men should act and communicate; and how individuals communicate establishes meanings of gender that in turn, influence cultural views.”47 That being said, you can have a female that has a masculine gender and, conversely, a male that has a feminine gender. Gender is all about how society has taught one to perceive the surrounding environment. The different traits that an individual displays is how one interprets gender, while other traits depict how an individual was raised and developed. Heidi Reeder noted that “In Western culture the stereotypically masculine traits include aggressiveness, independence and task orientation. Stereotypically feminine traits include being helpful, warm and sincere.”48 Sex is predetermined, and in most cases, it cannot be changed, but gender, on the other hand, is fluid and can vary in many different ways.

Gender is formed at a young age and then reinforced for the remainder of a lifetime. That does not mean that gender cannot be changed; it just means that one would be going against what gender society deems an individual should be. Gender comes from communication from influential figures in a person’s life. Gender plays a major role in perceived closeness and disclosure.49

When we talk about gender, we are not considering what the person is born physically. Rather, we consider what the person feels psychologically. Sandra Bem (1974) was interested in gender roles. She created a Bem Sex Role Inventory (BSRI). Based on her findings, she was able to categorized four types of genders: feminine, masculine, androgynous (a combination of both feminine and masculine traits), and undifferentiated (neither masculine or feminine).50 When you combine sex and gender together, you can have eight different combinations: masculine males, feminine males, androgynous males, undifferentiated males, masculine females, feminine females, androgynous females, undifferentiated females.51 Most people will perceive themselves as sex-typed or androgynous, rather than undifferentiated.

Bem’s work in gender has been eye-opening. She contended that there are three main gender perspectives in Western culture. First, males and females are psychologically different. Second, males are considered more dominating than females. Third, the differences between males and females are natural. If we can understand these basic differences, then we can communicate and function better.

Gender Differences in Interpersonal Communication

Each of the gender types will communicate differently. Feminine females will perceive interpersonal relationships as possibilities to nurture, to articulate their emotions and feelings. Whereas, masculine males will view interpersonal relationships as competition and the potential for gaining something. Androgynous male and androgynous females do not differ much in terms of their perceptions of interpersonal relationships. However, androgynous males and females, as well as feminine females are likely to sympathize with others more than masculine males.52

Sex Differences in Interpersonal Communication

In the United States, we have expectations for how males and females should communicate and behave.53 We learn sex differences at a very young age. Boys and girls play, perform, dress, and respond to thinks very differently. Girls are taught that it is okay to cry in public, but boys are taught to “be a man.” It is acceptable for boys to pretend to play guns and for girls to pretend to play being mothers. Males are conditioned to have instrumental roles, which are task-oriented responsibilities. Females are condition to have expressive roles, which are focused on helping and nurturing others or relationship-oriented.

Improving Communication Skills

Many popular guides to enhancing communication skills place particular emphasis on exploring your own needs, desires, and motives in the relationship. Some of the goals you have in a relationship may be subconscious. By becoming more aware of these goals, and what you want to achieve in a relationship, you can identify areas of the relationship that you would like to improve and generate ideas for making these changes.

Because people in relationships are interconnected and interdependent, it takes people willing to be open about their needs and relationship goals and willing to work on improving communication and, hence, the relationship in general.

As discussed previously, clear communication is necessary to give and receive information. Words have multiple denotations and connotations, and word choice is critical when you communicate about areas of your relationship that are not satisfying. Asking for and providing clarification and sending explicit messages, obtaining feedback to be sure that you are understood, and listening carefully to the feedback are all important components in effective communication. Finally, when you communicate, remember that everyone wants to be heard, to feel valued, to know that they matter, and to be assured that their ideas are important.

Key Takeaways

- Sex is biological, and gender is psychological.

- Males tend to communicate instrumentally, and females tend to communicate expressively.

- By becoming more aware of your goals and open to talk about the other person’s needs, you can improve your communication.

Exercises

- As a class, ask everyone to write down all the characteristics of males and females. Then, ask one person to write each word on a post-it note. Then, on the board in front of the class divide it into two sections: males and females. Each student will get the opportunity to put the words into the male or female section. Have a discussion to see if you all agree.

- Ask all the males to step out of the classroom and ask all the females to stay in the classroom. Each group will come up with ten questions that they always wanted to know about the opposite sex. For instance, why do girls open their mouths when putting on mascara? Or why do boys recall sports information so well? Come back into the classroom together and designate a spokesperson for each side. Males will ask their questions to the females, and females will ask their questions to the males. Each side will get to respond as a group. Why did you answer the way you did? Are there truly differences between males and females?

- On a sheet of paper, divide into two parts and label one side as male and one side as female. Complete the sentence: Males are_____ and Females are ______. Write your words on your paper. Try to write down ten possible answers for females and males. As a class, compare what you wrote down.

Key Terms

agape

Selfless love in which the needs of others are the priority.

androgynous

A person having both feminine and masculine characteristics.

attraction

Interest in another person and a desire to get to know him or her better.

avoiding

The stage of coming apart where you are creating distance from your partner.

bonding

The stage of coming together where you make a public announcement that your relationship exists.

circumscribing

The stage of coming apart where communication decreases. There are more arguments, working late, and there is less intimacy.

CL

Minimum standard of what is acceptable.

CL of alternatives

Comparison of what is happening in the relationship and what could be gained in another relationship.

compatible

Able to exist together harmoniously.

complementary

When one person can fulfill the other person’s needs.

contact frequency

This is how often you communicate with another person.

content level

Information that is communicated through the denotative and literal meanings of words.

demonstrative

Showing affection by touching or hugging other people.

differentiating

The stage of coming apart where both people are trying to figure out their own identities.

duration

The legnth of time of your relationship.

empathy

The ability to identify with and to understand how another person feels.

eros

Romantic love involving serial monogamous relationships.

experimenting

The stage of coming together; “small talk” occurs at this stage and you are searching for commonalities.

gender

The psychological characterisitcs that determine if a person is feminine or masculine.

goals

Expectations about how the relationship will function.

hedge

To use words or phrases that weaken the certainty of a statement.

initiating

The stage of coming together where a person is interested in making contact and it is brief.

instrumental

Roles that are focused on being task-oriented.

Integrating

This is the stage of coming together where you take on an identity as a social unit or give up characteristics of your old self.

intensifying

The stage of coming together where two people truly become a couple.

interaction variability

The ability to talk about various topics.

interdependent

A relationship in which people need each other or depend on each other in some way, and the actions of one person affect the other.

intimacy

Close and deeply personal contact with another person.

love

Love is a multidimensional concept that can include several different orientations toward the loved person such as romantic love (attraction based on physical beauty or handsomeness), best friend love, passionate love, unrequited love (love that is not returned), and companionate love (affectionate love and tenderness between people).

love style

Love style is considered an attitude that influences an individual’s perception of love.

ludus

Love in which games are played. Lying and deceit are acceptable.

mania

Obsessive love that requires constant reassurance.

physical attraction

The degree to which one person finds another person aesthetically pleasing.

platonic

A close relationship that is not physical.

pragma

Love involving logic and reason.

relationship

A connection, association, or attachment that people have with each other.

relationship dialectic

Tensions in a relationship where individuals need to deal with integration vs. separation, expression vs. privacy, and stability vs. change.

relationship level

The type of relationship between people evidenced as through their communication.

relationship maintenance

Strategies to help your relationship be successful and satisfying.

romantic relationships

Romantic relationships involve a bond of affection with a specific partner that researchers believe involves several psychological features: a desire for emotional closeness and union with the partner, caregiving, emotional dependency on the relationship and the partner, a separation anxiety when the other person is not there, and a willingness to sacrifice for the other love.

self-disclosure

The process of sharing information with another person.

sex

The biological characteristics that determine a person as male or female.

sharing

The process of revealing and disclosing information about yourself with another.

social attraction

The degree to which an individual sees another person as entertaining, intriguing, and fun to be around.

stagnating

The stage of coming apart where you are behaving in old familiar ways without much feeling. In other words, there is lost enthusiasm for old familiar things.

storge

Love that develops slowly out of friendship.

support

The ability to provide assistance, aid, or comfort to another.

symmetrical relationship

A relationship between people who see themselves as equals.

task attraction

The degree to which an individual is attracted to another person because they possess specific knowledge and/or skills that help that individual accomplish specific goals.

terminating

This is a summary of where the relationship has gone wrong and a desire to quit. It usually depends on: problems (sudden/gradual); negotiations to end (short/long); the outcome (end/continue in another form).

undifferentiated

A person who does not possess either masculine or feminine characteristics.

Chapter Wrap-Up

In this chapter, we’ve explored the range of issues related to building and maintaining relationships. We started by discussing the nature of relationships, which included a discussion of the characteristics of relationships and the importance of significant relationships. We then discussed the formation and dissolution of relationships. Then explored the importance of communication in relationships. Lastly, we looked at dating relationships and ended by discussing gender and relationships. Hopefully, you can see that building and maintain relationships takes a lot of work.

8.7 Chapter Exercises

Real-World Case Study