174

[latexpage]

Learning Objectives

- Describe the Davisson-Germer experiment, and explain how it provides evidence for the wave nature of electrons.

De Broglie Wavelength

In 1923 a French physics graduate student named Prince Louis-Victor de Broglie (1892–1987) made a radical proposal based on the hope that nature is symmetric. If EM radiation has both particle and wave properties, then nature would be symmetric if matter also had both particle and wave properties. If what we once thought of as an unequivocal wave (EM radiation) is also a particle, then what we think of as an unequivocal particle (matter) may also be a wave. De Broglie’s suggestion, made as part of his doctoral thesis, was so radical that it was greeted with some skepticism. A copy of his thesis was sent to Einstein, who said it was not only probably correct, but that it might be of fundamental importance. With the support of Einstein and a few other prominent physicists, de Broglie was awarded his doctorate.

De Broglie took both relativity and quantum mechanics into account to develop the proposal that all particles have a wavelength, given by

where \(h\) is Planck’s constant and \(p\) is momentum. This is defined to be the de Broglie wavelength. (Note that we already have this for photons, from the equation \(p=h/\lambda \).) The hallmark of a wave is interference. If matter is a wave, then it must exhibit constructive and destructive interference. Why isn’t this ordinarily observed? The answer is that in order to see significant interference effects, a wave must interact with an object about the same size as its wavelength. Since \(h\) is very small, \(\lambda \) is also small, especially for macroscopic objects. A 3-kg bowling ball moving at 10 m/s, for example, has

This means that to see its wave characteristics, the bowling ball would have to interact with something about \({\text{10}}^{\text{–35}}\phantom{\rule{0.25em}{0ex}}\text{m}\) in size—far smaller than anything known. When waves interact with objects much larger than their wavelength, they show negligible interference effects and move in straight lines (such as light rays in geometric optics). To get easily observed interference effects from particles of matter, the longest wavelength and hence smallest mass possible would be useful. Therefore, this effect was first observed with electrons.

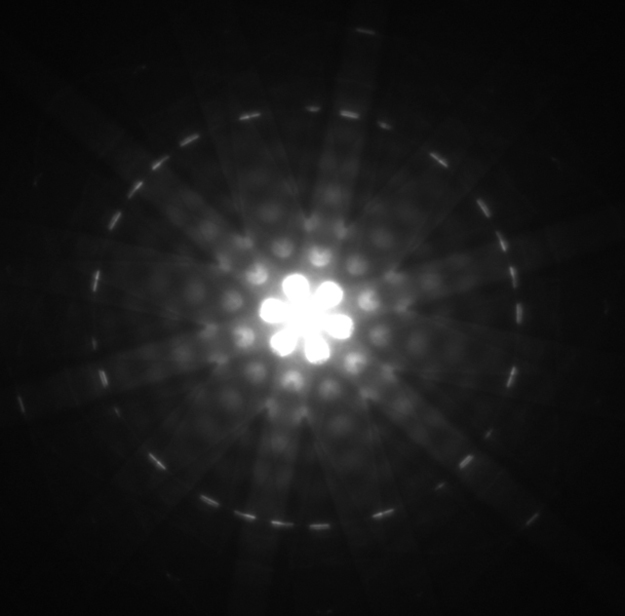

American physicists Clinton J. Davisson and Lester H. Germer in 1925 and, independently, British physicist G. P. Thomson (son of J. J. Thomson, discoverer of the electron) in 1926 scattered electrons from crystals and found diffraction patterns. These patterns are exactly consistent with interference of electrons having the de Broglie wavelength and are somewhat analogous to light interacting with a diffraction grating. (See (Figure).)

All microscopic particles, whether massless, like photons, or having mass, like electrons, have wave properties. The relationship between momentum and wavelength is fundamental for all particles.

De Broglie’s proposal of a wave nature for all particles initiated a remarkably productive era in which the foundations for quantum mechanics were laid. In 1926, the Austrian physicist Erwin Schrödinger (1887–1961) published four papers in which the wave nature of particles was treated explicitly with wave equations. At the same time, many others began important work. Among them was German physicist Werner Heisenberg (1901–1976) who, among many other contributions to quantum mechanics, formulated a mathematical treatment of the wave nature of matter that used matrices rather than wave equations. We will deal with some specifics in later sections, but it is worth noting that de Broglie’s work was a watershed for the development of quantum mechanics. De Broglie was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1929 for his vision, as were Davisson and G. P. Thomson in 1937 for their experimental verification of de Broglie’s hypothesis.

For an electron having a de Broglie wavelength of 0.167 nm (appropriate for interacting with crystal lattice structures that are about this size): (a) Calculate the electron’s velocity, assuming it is nonrelativistic. (b) Calculate the electron’s kinetic energy in eV.

Strategy

For part (a), since the de Broglie wavelength is given, the electron’s velocity can be obtained from \(\lambda =h/p\) by using the nonrelativistic formula for momentum, \(p=\text{mv.}\) For part (b), once \(v\) is obtained (and it has been verified that \(v\) is nonrelativistic), the classical kinetic energy is simply \(\left(1/2\right){\text{mv}}^{2}\text{.}\)

Solution for (a)

Substituting the nonrelativistic formula for momentum (\(p=\text{mv}\)) into the de Broglie wavelength gives

Solving for \(v\) gives

Substituting known values yields

Solution for (b)

While fast compared with a car, this electron’s speed is not highly relativistic, and so we can comfortably use the classical formula to find the electron’s kinetic energy and convert it to eV as requested.

Discussion

This low energy means that these 0.167-nm electrons could be obtained by accelerating them through a 54.0-V electrostatic potential, an easy task. The results also confirm the assumption that the electrons are nonrelativistic, since their velocity is just over 1% of the speed of light and the kinetic energy is about 0.01% of the rest energy of an electron (0.511 MeV). If the electrons had turned out to be relativistic, we would have had to use more involved calculations employing relativistic formulas.

Electron Microscopes

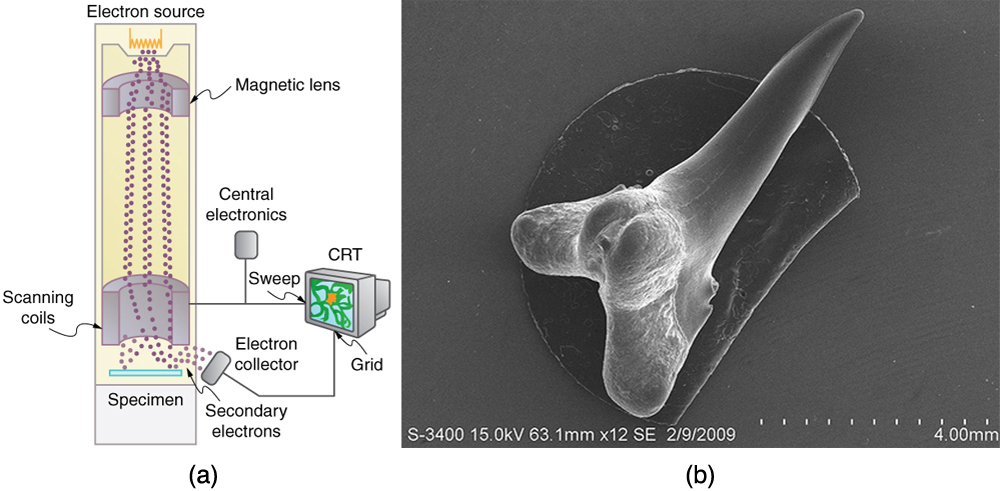

One consequence or use of the wave nature of matter is found in the electron microscope. As we have discussed, there is a limit to the detail observed with any probe having a wavelength. Resolution, or observable detail, is limited to about one wavelength. Since a potential of only 54 V can produce electrons with sub-nanometer wavelengths, it is easy to get electrons with much smaller wavelengths than those of visible light (hundreds of nanometers). Electron microscopes can, thus, be constructed to detect much smaller details than optical microscopes. (See (Figure).)

There are basically two types of electron microscopes. The transmission electron microscope (TEM) accelerates electrons that are emitted from a hot filament (the cathode). The beam is broadened and then passes through the sample. A magnetic lens focuses the beam image onto a fluorescent screen, a photographic plate, or (most probably) a CCD (light sensitive camera), from which it is transferred to a computer. The TEM is similar to the optical microscope, but it requires a thin sample examined in a vacuum. However it can resolve details as small as 0.1 nm (\({\text{10}}^{-\text{10}}\phantom{\rule{0.25em}{0ex}}m\)), providing magnifications of 100 million times the size of the original object. The TEM has allowed us to see individual atoms and structure of cell nuclei.

The scanning electron microscope (SEM) provides images by using secondary electrons produced by the primary beam interacting with the surface of the sample (see (Figure)). The SEM also uses magnetic lenses to focus the beam onto the sample. However, it moves the beam around electrically to “scan” the sample in the x and y directions. A CCD detector is used to process the data for each electron position, producing images like the one at the beginning of this chapter. The SEM has the advantage of not requiring a thin sample and of providing a 3-D view. However, its resolution is about ten times less than a TEM.

Electrons were the first particles with mass to be directly confirmed to have the wavelength proposed by de Broglie. Subsequently, protons, helium nuclei, neutrons, and many others have been observed to exhibit interference when they interact with objects having sizes similar to their de Broglie wavelength. The de Broglie wavelength for massless particles was well established in the 1920s for photons, and it has since been observed that all massless particles have a de Broglie wavelength \(\lambda =h/p.\) The wave nature of all particles is a universal characteristic of nature. We shall see in following sections that implications of the de Broglie wavelength include the quantization of energy in atoms and molecules, and an alteration of our basic view of nature on the microscopic scale. The next section, for example, shows that there are limits to the precision with which we may make predictions, regardless of how hard we try. There are even limits to the precision with which we may measure an object’s location or energy.

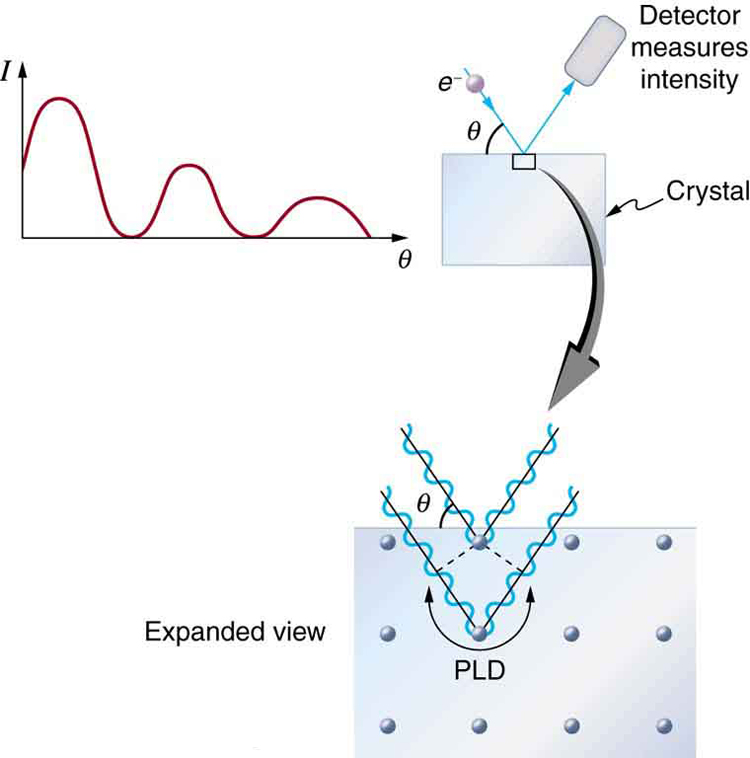

The wave nature of matter allows it to exhibit all the characteristics of other, more familiar, waves. Diffraction gratings, for example, produce diffraction patterns for light that depend on grating spacing and the wavelength of the light. This effect, as with most wave phenomena, is most pronounced when the wave interacts with objects having a size similar to its wavelength. For gratings, this is the spacing between multiple slits.) When electrons interact with a system having a spacing similar to the electron wavelength, they show the same types of interference patterns as light does for diffraction gratings, as shown at top left in (Figure).

Atoms are spaced at regular intervals in a crystal as parallel planes, as shown in the bottom part of (Figure). The spacings between these planes act like the openings in a diffraction grating. At certain incident angles, the paths of electrons scattering from successive planes differ by one wavelength and, thus, interfere constructively. At other angles, the path length differences are not an integral wavelength, and there is partial to total destructive interference. This type of scattering from a large crystal with well-defined lattice planes can produce dramatic interference patterns. It is called Bragg reflection, for the father-and-son team who first explored and analyzed it in some detail. The expanded view also shows the path-length differences and indicates how these depend on incident angle \(\theta \) in a manner similar to the diffraction patterns for x rays reflecting from a crystal.

Let us take the spacing between parallel planes of atoms in the crystal to be \(d\). As mentioned, if the path length difference (PLD) for the electrons is a whole number of wavelengths, there will be constructive interference—that is, \(\text{PLD}=\mathrm{n\lambda }\left(n=1, 2, 3,\dots \right)\). Because \(\text{AB}=\text{BC}=d\phantom{\rule{0.25em}{0ex}}\text{sin}\phantom{\rule{0.25em}{0ex}}\theta \text{,}\) we have constructive interference when \(\mathrm{n\lambda }=\text{2}d\phantom{\rule{0.25em}{0ex}}\text{sin}\phantom{\rule{0.25em}{0ex}}\mathrm{\theta .}\) This relationship is called the Bragg equation and applies not only to electrons but also to x rays.

The wavelength of matter is a submicroscopic characteristic that explains a macroscopic phenomenon such as Bragg reflection. Similarly, the wavelength of light is a submicroscopic characteristic that explains the macroscopic phenomenon of diffraction patterns.

Section Summary

- Particles of matter also have a wavelength, called the de Broglie wavelength, given by \(\lambda =\frac{h}{p}\), where \(p\) is momentum.

- Matter is found to have the same interference characteristics as any other wave.

Conceptual Questions

How does the interference of water waves differ from the interference of electrons? How are they analogous?

Describe one type of evidence for the wave nature of matter.

Describe one type of evidence for the particle nature of EM radiation.

Problems & Exercises

At what velocity will an electron have a wavelength of 1.00 m?

\(7.28×{\text{10}}^{–4}\phantom{\rule{0.25em}{0ex}}\text{m}\)

What is the wavelength of an electron moving at 3.00% of the speed of light?

At what velocity does a proton have a 6.00-fm wavelength (about the size of a nucleus)? Assume the proton is nonrelativistic. (1 femtometer = \({\text{10}}^{-\text{15}}\phantom{\rule{0.25em}{0ex}}\text{m.}\))

\(6.62×{\text{10}}^{7}\phantom{\rule{0.25em}{0ex}}\text{m/s}\)

What is the velocity of a 0.400-kg billiard ball if its wavelength is 7.50 cm (large enough for it to interfere with other billiard balls)?

Find the wavelength of a proton moving at 1.00% of the speed of light.

\(1.32×{\text{10}}^{–13}\phantom{\rule{0.25em}{0ex}}\text{m}\)

Experiments are performed with ultracold neutrons having velocities as small as 1.00 m/s. (a) What is the wavelength of such a neutron? (b) What is its kinetic energy in eV?

(a) Find the velocity of a neutron that has a 6.00-fm wavelength (about the size of a nucleus). Assume the neutron is nonrelativistic. (b) What is the neutron’s kinetic energy in MeV?

(a) \(6.62×{\text{10}}^{7}\phantom{\rule{0.25em}{0ex}}\text{m/s}\)

(b) \(22.9 MeV\)

What is the wavelength of an electron accelerated through a 30.0-kV potential, as in a TV tube?

What is the kinetic energy of an electron in a TEM having a 0.0100-nm wavelength?

(a) Calculate the velocity of an electron that has a wavelength of \(1\text{.}\text{00 μm.}\) (b) Through what voltage must the electron be accelerated to have this velocity?

The velocity of a proton emerging from a Van de Graaff accelerator is 25.0% of the speed of light. (a) What is the proton’s wavelength? (b) What is its kinetic energy, assuming it is nonrelativistic? (c) What was the equivalent voltage through which it was accelerated?

(a) 5.29 fm

(b) \(4\text{.}\text{70}×{\text{10}}^{-\text{12}}\phantom{\rule{0.25em}{0ex}}\text{J}\)

(c) 29.4 MV

The kinetic energy of an electron accelerated in an x-ray tube is 100 keV. Assuming it is nonrelativistic, what is its wavelength?

Unreasonable Results

(a) Assuming it is nonrelativistic, calculate the velocity of an electron with a 0.100-fm wavelength (small enough to detect details of a nucleus). (b) What is unreasonable about this result? (c) Which assumptions are unreasonable or inconsistent?

(a) \(7.28×{\text{10}}^{\text{12}}\phantom{\rule{0.25em}{0ex}}\text{m/s}\)

(b) This is thousands of times the speed of light (an impossibility).

(c) The assumption that the electron is non-relativistic is unreasonable at this wavelength.

Glossary

- de Broglie wavelength

- the wavelength possessed by a particle of matter, calculated by \(\lambda =h/p\)