1.2 The Evolution of Psychology: History, Approaches, and Questions

Learning Objectives

- Explain how psychology changed from a philosophical to a scientific discipline.

- List some of the most important questions that concern psychologists.

- Outline the basic schools of psychology and how each school has contributed to psychology.

In this section we will review the history of psychology with a focus on the important questions that psychologists ask and the major approaches (or schools) of psychological inquiry. The schools of psychology that we will review are summarized in Table 1.3, “The Most Important Approaches (Schools) of Psychology,” while Table 1.4, “History of Psychology,” presents a timeline of some of the most important psychologists, beginning with the early Greek philosophers and extending to the present day. Table 1.3 and Table 1.4 both represent a selection of the most important schools and people; to mention all the approaches and all the psychologists who have contributed to the field is not possible in one chapter. The approaches that psychologists have used to assess the issues that interest them have changed dramatically over the history of psychology. Perhaps most importantly, the field has moved steadily from speculation about behaviour toward a more objective and scientific approach as the technology available to study human behaviour has improved (Benjamin & Baker, 2004). There has also been an influx of women into the field. Although most early psychologists were men, now most psychologists, including the presidents of the most important psychological organizations, are women.

| [Skip Table] | ||

| School of Psychology | Description | Important Contributors |

|---|---|---|

| Structuralism | Uses the method of introspection to identify the basic elements or “structures” of psychological experience | Wilhelm Wundt, Edward B. Titchener |

| Functionalism | Attempts to understand why animals and humans have developed the particular psychological aspects that they currently possess | William James |

| Psychodynamic | Focuses on the role of our unconscious thoughts, feelings, and memories and our early childhood experiences in determining behaviour | Sigmund Freud, Carl Jung, Alfred Adler, Erik Erickson |

| Behaviourism | Based on the premise that it is not possible to objectively study the mind, and therefore that psychologists should limit their attention to the study of behaviour itself | John B. Watson, B. F. Skinner |

| Cognitive | The study of mental processes, including perception, thinking, memory, and judgments | Hermann Ebbinghaus, Sir Frederic Bartlett, Jean Piaget |

| Social-cultural | The study of how the social situations and the cultures in which people find themselves influence thinking and behaviour | Fritz Heider, Leon Festinger, Stanley Schachter |

Although most of the earliest psychologists were men, women are increasingly contributing to psychology. Here are some examples:

- 1968: Mary Jean Wright became the first woman president of the Canadian Psychological Association.

- 1970: Virginia Douglas became the second woman president of the Canadian Psychological Association.

- 1972: The Underground Symposium was held at the Canadian Psychological Association Convention. After having their individual papers and then a symposium rejected by the Program Committee, a group of six graduate students and non-tenured faculty, including Sandra Pyke and Esther Greenglass, held an independent research symposium that showcased work being done in the field of the psychology of women.

- 1976: The Canadian Research Institute for the Advancement of Women was founded.

- 1987: Janet Stoppard led the Women and Mental Health Committee of the Canadian Mental Health Association.

Although it cannot capture every important psychologist, the following timeline shows some of the most important contributors to the history of psychology. (Adapted by J. Walinga.)

| [Skip Table] | ||

| Date | Psychologist(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 428 to 347 BCE | Plato | Greek philosopher who argued for the role of nature in psychological development. |

| 384 to 432 BCE | Aristotle | Greek philosopher who argued for the role of nurture in psychological development. |

| 1588 to 1679 CE | Thomas Hobbes | English philosopher. |

| 1596 to 1650 | René Descartes | French philosopher. |

| 1632 to 1704 | John Locke | English philosopher. |

| 1712 to 1778 | Jean-Jacques Rousseau | French philosopher. |

| 1801 to 1887 | Gustav Fechner | German experimental psychologist who developed the idea of the “just noticeable difference” (JND), which is considered to be the first empirical psychological measurement. |

| 1809 to 1882 | Charles Darwin | British naturalist whose theory of natural selection influenced the functionalist school and the field of evolutionary psychology. |

| 1832 to 1920 | Wilhelm Wundt | German psychologist who opened one of the first psychology laboratories and helped develop the field of structuralism. |

| 1842 to 1910 | William James | American psychologist who opened one of the first psychology laboratories and helped develop the field of functionalism. |

| 1849 to 1936 | Ivan Pavlov | Russian psychologist whose experiments on learning led to the principles of classical conditioning. |

| 1850 to 1909 | Hermann Ebbinghaus | German psychologist who studied the ability of people to remember lists of nonsense syllables under different conditions. |

| 1856 to 1939 | Sigmund Freud | Austrian psychologist who founded the field of psychodynamic psychology. |

| 1867 to 1927 | Edward Bradford Titchener | American psychologist who contributed to the field of structuralism. |

| 1878 to 1958 | John B. Watson | American psychologist who contributed to the field of behavioralism. |

| 1886 to 1969 | Sir Frederic Bartlett | British psychologist who studied the cognitive and social processes of remembering. |

| 1896 to 1980 | Jean Piaget | Swiss psychologist who developed an important theory of cognitive development in children. |

| 1904 to 1990 | B. F. Skinner | American psychologist who contributed to the school of behaviourism. |

| 1926 to 1993 | Donald Broadbent | British cognitive psychologist who was pioneer in the study of attention. |

| 20th and 21st centuries | Linda Bartoshuk; Daniel Kahneman; Elizabeth Loftus; Geroge Miller. | American psychologists who contributed to the cognitive school of psychology by studying learning, memory, and judgment. An important contribution is the advancement of the field of neuroscience. Daniel Kahneman won the Nobel Prize in Economics for his work on psychological decision making. |

| 1850 | Dorothea Dix | Canadian psychologist known for her contributions to mental health and opened one of the first mental hospitals in Halifax, Nova Scotia. |

| 1880 | William Lyall; James Baldwin | Canadian psychologists who wrote early psychology texts and created first Canadian psychology lab at the University of Toronto. |

| 1950 | James Olds; Brenda Milner; Wilder Penfield; Donald Hebb; Endel Telving | Canadian psychologists who contributed to neurological psychology and opened the Montreal Neurological Institute. |

| 1960 | Albert Bandura | Canadian psychologist who developed ‘social learning theory’ with his Bobo doll studies illustrating the impact that observation and interaction has on learning. |

| 1970 | Hans Selye | Canadian psychologist who contributed significantly in the area of psychology of stress. |

Although psychology has changed dramatically over its history, the most important questions that psychologists address have remained constant. Some of these questions follow, and we will discuss them both in this chapter and in the chapters to come:

- Nature versus nurture. Are genes or environment most influential in determining the behaviour of individuals and in accounting for differences among people? Most scientists now agree that both genes and environment play crucial roles in most human behaviours, and yet we still have much to learn about how nature (our biological makeup) and nurture (the experiences that we have during our lives) work together (Harris, 1998; Pinker, 2002). The proportion of the observed differences of characteristics among people (e.g., in terms of their height, intelligence, or optimism) that is due to genetics is known as the heritability of the characteristic, and we will make much use of this term in the chapters to come. We will see, for example, that the heritability of intelligence is very high (about .85 out of 1.0) and that the heritability of extraversion is about .50. But we will also see that nature and nurture interact in complex ways, making the question “Is it nature or is it nurture?” very difficult to answer.

- Free will versus determinism. This question concerns the extent to which people have control over their own actions. Are we the products of our environment, guided by forces out of our control, or are we able to choose the behaviours we engage in? Most of us like to believe in free will, that we are able to do what we want—for instance, that we could get up right now and go fishing. And our legal system is premised on the concept of free will; we punish criminals because we believe that they have choice over their behaviours and freely choose to disobey the law. But as we will discuss later in the research focus in this section, recent research has suggested that we may have less control over our own behaviour than we think we do (Wegner, 2002).

- Accuracy versus inaccuracy. To what extent are humans good information processors? Although it appears that people are good enough to make sense of the world around them and to make decent decisions (Fiske, 2003), they are far from perfect. Human judgment is sometimes compromised by inaccuracies in our thinking styles and by our motivations and emotions. For instance, our judgment may be affected by our desires to gain material wealth and to see ourselves positively and by emotional responses to the events that happen to us. Many studies have explored decision making in crisis situations such as natural disasters, or human error or criminal action, such as in the cases of the Tylenol poisoning, the Maple Leaf meats listeriosis outbreak, the SARS epidemic or the Lac-Mégantic train derailment (Figure 1.2).

- Conscious versus unconscious processing. To what extent are we conscious of our own actions and the causes of them, and to what extent are our behaviours caused by influences that we are not aware of? Many of the major theories of psychology, ranging from the Freudian psychodynamic theories to contemporary work in cognitive psychology, argue that much of our behaviour is determined by variables that we are not aware of.

- Differences versus similarities. To what extent are we all similar, and to what extent are we different? For instance, are there basic psychological and personality differences between men and women, or are men and women by and large similar? And what about people from different ethnicities and cultures? Are people around the world generally the same, or are they influenced by their backgrounds and environments in different ways? Personality, social, and cross-cultural psychologists attempt to answer these classic questions.

Early Psychologists

The earliest psychologists that we know about are the Greek philosophers Plato (428-347 BC) and Aristotle (384-322 BC). These philosophers (see Figure 1.3) asked many of the same questions that today’s psychologists ask; for instance, they questioned the distinction between nature and nurture and the existence of free will. In terms of the former, Plato argued on the nature side, believing that certain kinds of knowledge are innate or inborn, whereas Aristotle was more on the nurture side, believing that each child is born as an “empty slate” (in Latin, a tabula rasa) and that knowledge is primarily acquired through learning and experience.

European philosophers continued to ask these fundamental questions during the Renaissance. For instance, the French philosopher René Descartes (1596-1650) also considered the issue of free will, arguing in its favour and believing that the mind controls the body through the pineal gland in the brain (an idea that made some sense at the time but was later proved incorrect). Descartes also believed in the existence of innate natural abilities. A scientist as well as a philosopher, Descartes dissected animals and was among the first to understand that the nerves controlled the muscles. He also addressed the relationship between mind (the mental aspects of life) and body (the physical aspects of life). Descartes believed in the principle of dualism: that the mind is fundamentally different from the mechanical body. Other European philosophers, including Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679), John Locke (1632-1704), and Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778), also weighed in on these issues. The fundamental problem that these philosophers faced was that they had few methods for settling their claims. Most philosophers didn’t conduct any research on these questions, in part because they didn’t yet know how to do it, and in part because they weren’t sure it was even possible to objectively study human experience. But dramatic changes came during the 1800s with the help of the first two research psychologists: the German psychologist Wilhelm Wundt (1832-1920), who developed a psychology laboratory in Leipzig, Germany, and the American psychologist William James (1842-1910), who founded a psychology laboratory at Harvard University.

Structuralism: Introspection and the Awareness of Subjective Experience

Wundt’s research in his laboratory in Leipzig focused on the nature of consciousness itself. Wundt and his students believed that it was possible to analyze the basic elements of the mind and to classify our conscious experiences scientifically. Wundt began the field known as structuralism, a school of psychology whose goal was to identify the basic elements or structures of psychological experience. Its goal was to create a periodic table of the elements of sensations, similar to the periodic table of elements that had recently been created in chemistry. Structuralists used the method of introspection to attempt to create a map of the elements of consciousness. Introspection involves asking research participants to describe exactly what they experience as they work on mental tasks, such as viewing colours, reading a page in a book, or performing a math problem. A participant who is reading a book might report, for instance, that he saw some black and coloured straight and curved marks on a white background. In other studies the structuralists used newly invented reaction time instruments to systematically assess not only what the participants were thinking but how long it took them to do so. Wundt discovered that it took people longer to report what sound they had just heard than to simply respond that they had heard the sound. These studies marked the first time researchers realized that there is a difference between the sensation of a stimulus and the perception of that stimulus, and the idea of using reaction times to study mental events has now become a mainstay of cognitive psychology.

Perhaps the best known of the structuralists was Edward Bradford Titchener (1867-1927). Titchener was a student of Wundt’s who came to the United States in the late 1800s and founded a laboratory at Cornell University (Figure 1.4). (Titchener was later rejected by McGill University (1903). Perhaps he was ahead of his time; Brenda Milner did not open the Montreal Neurological Institute until 1950.) In his research using introspection, Titchener and his students claimed to have identified more than 40,000 sensations, including those relating to vision, hearing, and taste. An important aspect of the structuralist approach was that it was rigorous and scientific. The research marked the beginning of psychology as a science, because it demonstrated that mental events could be quantified. But the structuralists also discovered the limitations of introspection. Even highly trained research participants were often unable to report on their subjective experiences. When the participants were asked to do simple math problems, they could easily do them, but they could not easily answer how they did them. Thus the structuralists were the first to realize the importance of unconscious processes—that many important aspects of human psychology occur outside our conscious awareness, and that psychologists cannot expect research participants to be able to accurately report on all of their experiences.

Functionalism and Evolutionary Psychology

In contrast to Wundt, who attempted to understand the nature of consciousness, William James and the other members of the school of functionalism aimed to understand why animals and humans have developed the particular psychological aspects that they currently possess (Hunt, 1993). For James, one’s thinking was relevant only to one’s behaviour. As he put it in his psychology textbook, “My thinking is first and last and always for the sake of my doing” (James, 1890). James and the other members of the functionalist school (Figure 1.5) were influenced by Charles Darwin’s (1809-1882) theory of natural selection, which proposed that the physical characteristics of animals and humans evolved because they were useful, or functional. The functionalists believed that Darwin’s theory applied to psychological characteristics too. Just as some animals have developed strong muscles to allow them to run fast, the human brain, so functionalists thought, must have adapted to serve a particular function in human experience.

Although functionalism no longer exists as a school of psychology, its basic principles have been absorbed into psychology and continue to influence it in many ways. The work of the functionalists has developed into the field of evolutionary psychology, a branch of psychology that applies the Darwinian theory of natural selection to human and animal behaviour (Dennett, 1995; Tooby & Cosmides, 1992). Evolutionary psychology accepts the functionalists’ basic assumption, namely that many human psychological systems, including memory, emotion, and personality, serve key adaptive functions. As we will see in the chapters to come, evolutionary psychologists use evolutionary theory to understand many different behaviours, including romantic attraction, stereotypes and prejudice, and even the causes of many psychological disorders. A key component of the ideas of evolutionary psychology is fitness. Fitness refers to the extent to which having a given characteristic helps the individual organism survive and reproduce at a higher rate than do other members of the species who do not have the characteristic. Fitter organisms pass on their genes more successfully to later generations, making the characteristics that produce fitness more likely to become part of the organism’s nature than characteristics that do not produce fitness. For example, it has been argued that the emotion of jealousy has survived over time in men because men who experience jealousy are more fit than men who do not. According to this idea, the experience of jealousy leads men to be more likely to protect their mates and guard against rivals, which increases their reproductive success (Buss, 2000). Despite its importance in psychological theorizing, evolutionary psychology also has some limitations. One problem is that many of its predictions are extremely difficult to test. Unlike the fossils that are used to learn about the physical evolution of species, we cannot know which psychological characteristics our ancestors possessed or did not possess; we can only make guesses about this. Because it is difficult to directly test evolutionary theories, it is always possible that the explanations we apply are made up after the fact to account for observed data (Gould & Lewontin, 1979). Nevertheless, the evolutionary approach is important to psychology because it provides logical explanations for why we have many psychological characteristics.

Psychodynamic Psychology

Perhaps the school of psychology that is most familiar to the general public is the psychodynamic approach to understanding behaviour, which was championed by Sigmund Freud (1856-1939) and his followers. Psychodynamic psychology is an approach to understanding human behaviour that focuses on the role of unconscious thoughts, feelings, and memories. Freud (Figure 1.6) developed his theories about behaviour through extensive analysis of the patients that he treated in his private clinical practice. Freud believed that many of the problems that his patients experienced, including anxiety, depression, and sexual dysfunction, were the result of the effects of painful childhood experiences that they could no longer remember.

Freud’s ideas were extended by other psychologists whom he influenced, including Carl Jung (1875-1961), Alfred Adler (1870-1937), Karen Horney (1855-1952), and Erik Erikson (1902-1994). These and others who follow the psychodynamic approach believe that it is possible to help the patient if the unconscious drives can be remembered, particularly through a deep and thorough exploration of the person’s early sexual experiences and current sexual desires. These explorations are revealed through talk therapy and dream analysis in a process called psychoanalysis. The founders of the school of psychodynamics were primarily practitioners who worked with individuals to help them understand and confront their psychological symptoms. Although they did not conduct much research on their ideas, and although later, more sophisticated tests of their theories have not always supported their proposals, psychodynamics has nevertheless had substantial impact on the field of psychology, and indeed on thinking about human behaviour more generally (Moore & Fine, 1995). The importance of the unconscious in human behaviour, the idea that early childhood experiences are critical, and the concept of therapy as a way of improving human lives are all ideas that are derived from the psychodynamic approach and that remain central to psychology.

Behaviourism and the Question of Free Will

Although they differed in approach, both structuralism and functionalism were essentially studies of the mind. The psychologists associated with the school of behaviourism, on the other hand, were reacting in part to the difficulties psychologists encountered when they tried to use introspection to understand behaviour. Behaviourism is a school of psychology that is based on the premise that it is not possible to objectively study the mind, and therefore that psychologists should limit their attention to the study of behaviour itself. Behaviourists believe that the human mind is a black box into which stimuli are sent and from which responses are received. They argue that there is no point in trying to determine what happens in the box because we can successfully predict behaviour without knowing what happens inside the mind. Furthermore, behaviourists believe that it is possible to develop laws of learning that can explain all behaviours. The first behaviourist was the American psychologist John B. Watson (1878-1958). Watson was influenced in large part by the work of the Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov (1849-1936), who had discovered that dogs would salivate at the sound of a tone that had previously been associated with the presentation of food. Watson and the other behaviourists began to use these ideas to explain how events that people and other organisms experienced in their environment (stimuli) could produce specific behaviours (responses). For instance, in Pavlov’s research the stimulus (either the food or, after learning, the tone) would produce the response of salivation in the dogs. In his research Watson found that systematically exposing a child to fearful stimuli in the presence of objects that did not themselves elicit fear could lead the child to respond with a fearful behaviour to the presence of the objects (Watson & Rayner, 1920; Beck, Levinson, & Irons, 2009). In the best known of his studies, an eight-month-old boy named Little Albert was used as the subject. Here is a summary of the findings: The boy was placed in the middle of a room; a white laboratory rat was placed near him and he was allowed to play with it. The child showed no fear of the rat. In later trials, the researchers made a loud sound behind Albert’s back by striking a steel bar with a hammer whenever the baby touched the rat. The child cried when he heard the noise. After several such pairings of the two stimuli, the child was again shown the rat. Now, however, he cried and tried to move away from the rat. In line with the behaviourist approach, the boy had learned to associate the white rat with the loud noise, resulting in crying.

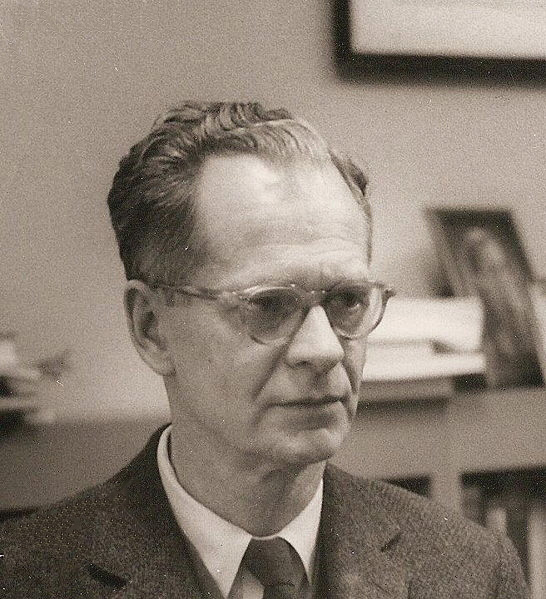

The most famous behaviourist was Burrhus Frederick (B. F.) Skinner (1904 to 1990), who expanded the principles of behaviourism and also brought them to the attention of the public at large. Skinner (Figure 1.7) used the ideas of stimulus and response, along with the application of rewards or reinforcements, to train pigeons and other animals. And he used the general principles of behaviourism to develop theories about how best to teach children and how to create societies that were peaceful and productive. Skinner even developed a method for studying thoughts and feelings using the behaviourist approach (Skinner, 1957, 1972).

Research Focus: Do We Have Free Will?

The behaviourist research program had important implications for the fundamental questions about nature and nurture and about free will. In terms of the nature-nurture debate, the behaviourists agreed with the nurture approach, believing that we are shaped exclusively by our environments. They also argued that there is no free will, but rather that our behaviours are determined by the events that we have experienced in our past. In short, this approach argues that organisms, including humans, are a lot like puppets in a show who don’t realize that other people are controlling them. Furthermore, although we do not cause our own actions, we nevertheless believe that we do because we don’t realize all the influences acting on our behaviour.

Recent research in psychology has suggested that Skinner and the behaviourists might well have been right, at least in the sense that we overestimate our own free will in responding to the events around us (Libet, 1985; Matsuhashi & Hallett, 2008; Wegner, 2002). In one demonstration of the misperception of our own free will, neuroscientists Soon, Brass, Heinze, and Haynes (2008) placed their research participants in a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) brain scanner while they presented them with a series of letters on a computer screen. The letter on the screen changed every half second. The participants were asked, whenever they decided to, to press either of two buttons. Then they were asked to indicate which letter was showing on the screen when they decided to press the button. The researchers analyzed the brain images to see if they could predict which of the two buttons the participant was going to press, even before the letter at which he or she had indicated the decision to press a button. Suggesting that the intention to act occurred in the brain before the research participants became aware of it, the researchers found that the prefrontal cortex region of the brain showed activation that could be used to predict the button pressed as long as 10 seconds before the participants said that they had decided which button to press.

Research has found that we are more likely to think that we control our behaviour when the desire to act occurs immediately prior to the outcome, when the thought is consistent with the outcome, and when there are no other apparent causes for the behaviour. Aarts, Custers, and Wegner (2005) asked their research participants to control a rapidly moving square along with a computer that was also controlling the square independently. The participants pressed a button to stop the movement. When participants were exposed to words related to the location of the square just before they stopped its movement, they became more likely to think that they controlled the motion, even when it was actually the computer that stopped it. And Dijksterhuis, Preston, Wegner, and Aarts (2008) found that participants who had just been exposed to first-person singular pronouns, such as “I” and “me,” were more likely to believe that they controlled their actions than were people who had seen the words “computer” or “God.” The idea that we are more likely to take ownership for our actions in some cases than in others is also seen in our attributions for success and failure. Because we normally expect that our behaviours will be met with success, when we are successful we easily believe that the success is the result of our own free will. When an action is met with failure, on the other hand, we are less likely to perceive this outcome as the result of our free will, and we are more likely to blame the outcome on luck or our teacher (Wegner, 2003).

The behaviourists made substantial contributions to psychology by identifying the principles of learning. Although the behaviourists were incorrect in their beliefs that it was not possible to measure thoughts and feelings, their ideas provided new ideas that helped further our understanding regarding the nature-nurture debate and the question of free will. The ideas of behaviourism are fundamental to psychology and have been developed to help us better understand the role of prior experiences in a variety of areas of psychology.

The Cognitive Approach and Cognitive Neuroscience

Science is always influenced by the technology that surrounds it, and psychology is no exception. Thus it is no surprise that beginning in the 1960s, growing numbers of psychologists began to think about the brain and about human behaviour in terms of the computer, which was being developed and becoming publicly available at that time. The analogy between the brain and the computer, although by no means perfect, provided part of the impetus for a new school of psychology called cognitive psychology. Cognitive psychology is a field of psychology that studies mental processes, including perception, thinking, memory, and judgment. These actions correspond well to the processes that computers perform. Although cognitive psychology began in earnest in the 1960s, earlier psychologists had also taken a cognitive orientation. Some of the important contributors to cognitive psychology include the German psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus (1850-1909), who studied the ability of people to remember lists of words under different conditions, and the English psychologist Sir Frederic Bartlett (1886-1969), who studied the cognitive and social processes of remembering. Bartlett created short stories that were in some ways logical but also contained some very unusual and unexpected events. Bartlett discovered that people found it very difficult to recall the stories exactly, even after being allowed to study them repeatedly, and he hypothesized that the stories were difficult to remember because they did not fit the participants’ expectations about how stories should go. The idea that our memory is influenced by what we already know was also a major idea behind the cognitive-developmental stage model of Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget (1896-1980). Other important cognitive psychologists include Donald E. Broadbent (1926-1993), Daniel Kahneman (1934-), George Miller (1920-2012), Eleanor Rosch (1938-), and Amos Tversky (1937-1996).

The War of the Ghosts

The War of the Ghosts is a story that was used by Sir Frederic Bartlett to test the influence of prior expectations on memory. Bartlett found that even when his British research participants were allowed to read the story many times, they still could not remember it well, and he believed this was because it did not fit with their prior knowledge. One night two young men from Egulac went down to the river to hunt seals, and while they were there it became foggy and calm. Then they heard war-cries, and they thought: “Maybe this is a war-party.” They escaped to the shore, and hid behind a log. Now canoes came up, and they heard the noise of paddles and saw one canoe coming up to them. There were five men in the canoe, and they said: “What do you think? We wish to take you along. We are going up the river to make war on the people.” One of the young men said, “I have no arrows.” “Arrows are in the canoe,” they said. “I will not go along. I might be killed. My relatives do not know where I have gone. But you,” he said, turning to the other, “may go with them.” So one of the young men went, but the other returned home. And the warriors went on up the river to a town on the other side of Kalama. The people came down to the water and they began to fight, and many were killed. But presently the young man heard one of the warriors say, “Quick, let us go home: that Indian has been hit.” Now he thought: “Oh, they are ghosts.” He did not feel sick, but they said he had been shot. So the canoes went back to Egulac and the young man went ashore to his house and made a fire. And he told everybody and said: “Behold I accompanied the ghosts, and we went to fight. Many of our fellows were killed, and many of those who attacked us were killed. They said I was hit, and I did not feel sick.” He told it all, and then he became quiet. When the sun rose he fell down. Something black came out of his mouth. His face became contorted. The people jumped up and cried. He was dead. (Bartlett, 1932)

In its argument that our thinking has a powerful influence on behaviour, the cognitive approach provided a distinct alternative to behaviourism. According to cognitive psychologists, ignoring the mind itself will never be sufficient because people interpret the stimuli that they experience. For instance, when a boy turns to a girl on a date and says, “You are so beautiful,” a behaviourist would probably see that as a reinforcing (positive) stimulus. And yet the girl might not be so easily fooled. She might try to understand why the boy is making this particular statement at this particular time and wonder if he might be attempting to influence her through the comment. Cognitive psychologists maintain that when we take into consideration how stimuli are evaluated and interpreted, we understand behaviour more deeply. Cognitive psychology remains enormously influential today, and it has guided research in such varied fields as language, problem solving, memory, intelligence, education, human development, social psychology, and psychotherapy. The cognitive revolution has been given even more life over the past decade as the result of recent advances in our ability to see the brain in action using neuroimaging techniques. Neuroimaging is the use of various techniques to provide pictures of the structure and function of the living brain (Ilardi & Feldman, 2001). These images are used to diagnose brain disease and injury, but they also allow researchers to view information processing as it occurs in the brain, because the processing causes the involved area of the brain to increase metabolism and show up on the scan. We have already discussed the use of one neuroimaging technique, functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), in the research focus earlier in this section, and we will discuss the use of neuroimaging techniques in many areas of psychology in the chapters to follow.

Social-Cultural Psychology

A final school, which takes a higher level of analysis and which has had substantial impact on psychology, can be broadly referred to as the social-cultural approach. The field of social-cultural psychology is the study of how the social situations and the cultures in which people find themselves influence thinking and behaviour. Social-cultural psychologists are particularly concerned with how people perceive themselves and others, and how people influence each other’s behaviour. For instance, social psychologists have found that we are attracted to others who are similar to us in terms of attitudes and interests (Byrne, 1969), that we develop our own beliefs and attitudes by comparing our opinions to those of others (Festinger, 1954), and that we frequently change our beliefs and behaviours to be similar to those of the people we care about—a process known as conformity. An important aspect of social-cultural psychology are social norms—the ways of thinking, feeling, or behaving that are shared by group members and perceived by them as appropriate (Asch, 1952; Cialdini, 1993). Norms include customs, traditions, standards, and rules, as well as the general values of the group. Many of the most important social norms are determined by the culture in which we live, and these cultures are studied by cross-cultural psychologists. A culture represents the common set of social norms, including religious and family values and other moral beliefs, shared by the people who live in a geographical region (Fiske, Kitayama, Markus, & Nisbett, 1998; Markus, Kitayama, & Heiman, 1996; Matsumoto, 2001). Cultures influence every aspect of our lives, and it is not inappropriate to say that our culture defines our lives just as much as does our evolutionary experience (Mesoudi, 2009). Psychologists have found that there is a fundamental difference in social norms between Western cultures (including those in Canada, the United States, Western Europe, Australia, and New Zealand) and East Asian cultures (including those in China, Japan, Taiwan, Korea, India, and Southeast Asia). Norms in Western cultures are primarily oriented toward individualism, which is about valuing the self and one’s independence from others. Children in Western cultures are taught to develop and to value a sense of their personal self, and to see themselves in large part as separate from the other people around them. Children in Western cultures feel special about themselves; they enjoy getting gold stars on their projects and the best grade in the class. Adults in Western cultures are oriented toward promoting their own individual success, frequently in comparison to (or even at the expense of) others. Norms in the East Asian culture, on the other hand, are oriented toward interdependence or collectivism. In these cultures children are taught to focus on developing harmonious social relationships with others. The predominant norms relate to group togetherness and connectedness, and duty and responsibility to one’s family and other groups. When asked to describe themselves, the members of East Asian cultures are more likely than those from Western cultures to indicate that they are particularly concerned about the interests of others, including their close friends and their colleagues (Figure 1.8, “East vs West”).

Another important cultural difference is the extent to which people in different cultures are bound by social norms and customs, rather than being free to express their own individuality without considering social norms (Chan, Gelfand, Triandis, & Tzeng, 1996). Cultures also differ in terms of personal space, such as how closely individuals stand to each other when talking, as well as the communication styles they employ. It is important to be aware of cultures and cultural differences because people with different cultural backgrounds increasingly come into contact with each other as a result of increased travel and immigration and the development of the Internet and other forms of communication. In Canada, for instance, there are many different ethnic groups, and the proportion of the population that comes from minority (non-White) groups is increasing from year to year. The social-cultural approach to understanding behaviour reminds us again of the difficulty of making broad generalizations about human nature. Different people experience things differently, and they experience them differently in different cultures.

The Many Disciplines of Psychology

Psychology is not one discipline but rather a collection of many subdisciplines that all share at least some common approaches and that work together and exchange knowledge to form a coherent discipline (Yang & Chiu, 2009). Because the field of psychology is so broad, students may wonder which areas are most suitable for their interests and which types of careers might be available to them. Table 1.5, “Some Career Paths in Psychology,” will help you consider the answers to these questions. You can learn more about these different fields of psychology and the careers associated with them at http://www.psyccareers.com/.

| [Skip Table] | ||

| Psychology field | Description | Career opportunities |

|---|---|---|

| Biopsychology and neuroscience | This field examines the physiological bases of behaviour in animals and humans by studying the functioning of different brain areas and the effects of hormones and neurotransmitters on behaviour. | Most biopsychologists work in research settings—for instance, at universities, for the federal government, and in private research labs. |

| Clinical and counselling psychology | These are the largest fields of psychology. The focus is on the assessment, diagnosis, causes, and treatment of mental disorders. | Clinical and counseling psychologists provide therapy to patients with the goal of improving their life experiences. They work in hospitals, schools, social agencies, and private practice. Because the demand for this career is high, entry to academic programs is highly competitive. |

| Cognitive psychology | This field uses sophisticated research methods, including reaction time and brain imaging, to study memory, language, and thinking of humans. | Cognitive psychologists work primarily in research settings, although some (such as those who specialize in human-computer interactions) consult for businesses. |

| Developmental psychology | These psychologists conduct research on the cognitive, emotional, and social changes that occur across the lifespan. | Many work in research settings, although others work in schools and community agencies to help improve and evaluate the effectiveness of intervention programs such as Head Start. |

| Forensic psychology | Forensic psychologists apply psychological principles to understand the behaviour of judges, lawyers, courtroom juries, and others in the criminal justice system. | Forensic psychologists work in the criminal justice system. They may testify in court and may provide information about the reliability of eyewitness testimony and jury selection. |

| Health psychology | Health psychologists are concerned with understanding how biology, behaviour, and the social situation influence health and illness. | Health psychologists work with medical professionals in clinical settings to promote better health, conduct research, and teach at universities. |

| Industrial-organizational and environmental psychology | Industrial-organizational psychology applies psychology to the workplace with the goal of improving the performance and well-being of employees. | There are a wide variety of career opportunities in these fields, generally working in businesses. These psychologists help select employees, evaluate employee performance, and examine the effects of different working conditions on behaviour. They may also work to design equipment and environments that improve employee performance and reduce accidents. |

| Personality psychology | These psychologists study people and the differences among them. The goal is to develop theories that explain the psychological processes of individuals, and to focus on individual differences. | Most work in academic settings, but the skills of personality psychologists are also in demand in business—for instance, in advertising and marketing. PhD programs in personality psychology are often connected with programs in social psychology. |

| School and educational psychology | This field studies how people learn in school, the effectiveness of school programs, and the psychology of teaching. | School psychologists work in elementary and secondary schools or school district offices with students, teachers, parents, and administrators. They may assess children’s psychological and learning problems and develop programs to minimize the impact of these problems. |

| Social and cross-cultural psychology | This field examines people’s interactions with other people. Topics of study include conformity, group behaviour, leadership, attitudes, and personal perception. | Many social psychologists work in marketing, advertising, organizational, systems design, and other applied psychology fields. |

| Sports psychology | This field studies the psychological aspects of sports behaviour. The goal is to understand the psychological factors that influence performance in sports, including the role of exercise and team interactions. | Sports psychologists work in gyms, schools, professional sports teams, and other areas where sports are practiced. |

Psychology in Everyday Life: How to Effectively Learn and Remember

One way that the findings of psychological research may be particularly helpful to you is in terms of improving your learning and study skills. Psychological research has provided a substantial amount of knowledge about the principles of learning and memory. This information can help you do better in this and other courses, and can also help you better learn new concepts and techniques in other areas of your life. The most important thing you can learn in college is how to better study, learn, and remember. These skills will help you throughout your life, as you learn new jobs and take on other responsibilities. There are substantial individual differences in learning and memory, such that some people learn faster than others. But even if it takes you longer to learn than you think it should, the extra time you put into studying is well worth the effort. And you can learn to learn—learning to study effectively and to remember information is just like learning any other skill, such as playing a sport or a video game.

To learn well, you need to be ready to learn. You cannot learn well when you are tired, when you are under stress, or if you are abusing alcohol or drugs. Try to keep a consistent routine of sleeping and eating. Eat moderately and nutritiously, and avoid drugs that can impair memory, particularly alcohol. There is no evidence that stimulants such as caffeine, amphetamines, or any of the many “memory-enhancing drugs” on the market will help you learn (Gold, Cahill, & Wenk, 2002; McDaniel, Maier, & Einstein, 2002). Memory supplements are usually no more effective than drinking a can of sugared soda, which releases glucose and thus improves memory slightly.

Psychologists have studied the ways that best allow people to acquire new information, to retain it over time, and to retrieve information that has been stored in our memories. One important finding is that learning is an active process. To acquire information most effectively, we must actively manipulate it. One active approach is rehearsal—repeating the information that is to be learned over and over again. Although simple repetition does help us learn, psychological research has found that we acquire information most effectively when we actively think about or elaborate on its meaning and relate the material to something else. When you study, try to elaborate by connecting the information to other things that you already know. If you want to remember the different schools of psychology, for instance, try to think about how each of the approaches is different from the others. As you compare the approaches, determine what is most important about each one and then relate it to the features of the other approaches.

In an important study showing the effectiveness of elaborative encoding, Rogers, Kuiper, and Kirker (1977) found that students learned information best when they related it to aspects of themselves (a phenomenon known as the self-reference effect). This research suggests that imagining how the material relates to your own interests and goals will help you learn it. An approach known as the method of loci involves linking each of the pieces of information that you need to remember to places that you are familiar with. You might think about the house that you grew up in and the rooms in it. You could put the behaviourists in the bedroom, the structuralists in the living room, and the functionalists in the kitchen. Then when you need to remember the information, you retrieve the mental image of your house and should be able to “see” each of the people in each of the areas.

One of the most fundamental principles of learning is known as the spacing effect. Both humans and animals more easily remember or learn material when they study the material in several shorter study periods over a longer period of time, rather than studying it just once for a long period of time. Cramming for an exam is a particularly ineffective way to learn. Psychologists have also found that performance is improved when people set difficult yet realistic goals for themselves (Locke & Latham, 2006). You can use this knowledge to help you learn. Set realistic goals for the time you are going to spend studying and what you are going to learn, and try to stick to those goals. Do a small amount every day, and by the end of the week you will have accomplished a lot.

Our ability to adequately assess our own knowledge is known as metacognition. Research suggests that our metacognition may make us overconfident, leading us to believe that we have learned material even when we have not. To counteract this problem, don’t just go over your notes again and again. Instead, make a list of questions and then see if you can answer them. Study the information again and then test yourself again after a few minutes. If you made any mistakes, study again. Then wait for a half hour and test yourself again. Then test again after one day and after two days. Testing yourself by attempting to retrieve information in an active manner is better than simply studying the material because it will help you determine if you really know it. In summary, everyone can learn to learn better. Learning is an important skill, and following the previously mentioned guidelines will likely help you learn better.

Key Takeaways

- The first psychologists were philosophers, but the field became more empirical and objective as more sophisticated scientific approaches were developed and employed.

- Some basic questions asked by psychologists include those about nature versus nurture, free will versus determinism, accuracy versus inaccuracy, and conscious versus unconscious processing.

- The structuralists attempted to analyze the nature of consciousness using introspection.

- The functionalists based their ideas on the work of Darwin, and their approaches led to the field of evolutionary psychology.

- The behaviourists explained behaviour in terms of stimulus, response, and reinforcement, while denying the presence of free will.

- Cognitive psychologists study how people perceive, process, and remember information.

- Psychodynamic psychology focuses on unconscious drives and the potential to improve lives through psychoanalysis and psychotherapy.

- The social-cultural approach focuses on the social situation, including how cultures and social norms influence our behaviour.

Exercises and Critical Thinking

- What type of questions can psychologists answer that philosophers might not be able to answer as completely or as accurately? Explain why you think psychologists can answer these questions better than philosophers can.

- Choose one of the major questions of psychology and provide some evidence from your own experience that supports one side or the other.

- Choose two of the fields of psychology discussed in this section and explain how they differ in their approaches to understanding behaviour and the level of explanation at which they are focused.

References

Aarts, H., Custers, R., & Wegner, D. M. (2005). On the inference of personal authorship: Enhancing experienced agency by priming effect information. Consciousness and Cognition: An International Journal, 14(3), 439–458.

Asch, S. E. (1952). Social Psychology. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Bartlett, F. C. (1932). Remembering. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Beck, H. P., Levinson, S., & Irons, G. (2009). Finding Little Albert: A journey to John B. Watson’s infant laboratory. American Psychologist, 64(7), 605–614.

Benjamin, L. T., Jr., & Baker, D. B. (2004). From seance to science: A history of the profession of psychology in America. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thomson.

Buss, D. M. (2000). The dangerous passion: Why jealousy is as necessary as love and sex. New York, NY: Free Press.

Byrne, D. (1969). Attitudes and attraction. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 4, pp. 35–89). New York, NY: Academic Press.

Chan, D. K. S., Gelfand, M. J., Triandis, H. C., & Tzeng, O. (1996). Tightness-looseness revisited: Some preliminary analyses in Japan and the United States. International Journal of Psychology, 31, 1–12.

Cialdini, R. B. (1993). Influence: Science and practice (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Harper Collins College.

Dennett, D. (1995). Darwin’s dangerous idea: Evolution and the meanings of life. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster.

Dijksterhuis, A., Preston, J., Wegner, D. M., & Aarts, H. (2008). Effects of subliminal priming of self and God on self-attribution of authorship for events. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 44(1), 2–9.

Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations, 7, 117–140.

Fiske, S. T. (2003). Social beings. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Fiske, A., Kitayama, S., Markus, H., & Nisbett, R. (1998). The cultural matrix of social psychology. In D. Gilbert, S. Fiske, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), The handbook of social psychology (4th ed., pp. 915–981). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Gold, P. E., Cahill, L., & Wenk, G. L. (2002). Ginkgo biloba: A cognitive enhancer? Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 3(1), 2–11.

Gould, S. J., & Lewontin, R. C. (1979). The spandrels of San Marco and the Panglossian paradigm: A critique of the adaptationist programme. In Proceedings of the Royal Society of London (Series B), 205, 581–598.

Harris, J. (1998). The nurture assumption: Why children turn out the way they do. New York, NY: Touchstone Books.

Hunt, M. (1993). The story of psychology. New York, NY: Anchor Books.

Ilardi, S. S., & Feldman, D. (2001). The cognitive neuroscience paradigm: A unifying metatheoretical framework for the science and practice of clinical psychology. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 57(9), 1067–1088.

James, W. (1890). The principles of psychology. New York, NY: Dover.

Libet, B. (1985). Unconscious cerebral initiative and the role of conscious will in voluntary action. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 8(4), 529–566.

Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2006). New directions in goal-setting theory. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 15(5), 265–268.

Markus, H. R., Kitayama, S., & Heiman, R. J. (1996). Culture and “basic” psychological principles. In E. T. Higgins & A. W. Kruglanski (Eds.), Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles (pp. 857–913). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Matsuhashi, M., & Hallett, M. (2008). The timing of the conscious intention to move. European Journal of Neuroscience, 28(11), 2344–2351.

Matsumoto, D. (Ed.). (2001). The handbook of culture and psychology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

McDaniel, M.A., Maier, S.F., & Einstein, G.O. (2002). Brain-specific nutrients: A memory cure? Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 3, 11-37.

Mesoudi, A. (2009). How cultural evolutionary theory can inform social psychology and vice versa. Psychological Review, 116(4), 929–952.

Moore, B. E., & Fine, B. D. (1995). Psychoanalysis: The major concepts. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Pinker, S. (2002). The blank slate: The modern denial of human nature. New York, NY: Penguin Putnam.

Rogers, T. B., Kuiper, N. A., & Kirker, W. S. (1977). Self-reference and the encoding of personal information. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 35(9), 677–688.

Skinner, B. (1957). Verbal behavior. Acton, MA: Copley; Skinner, B. (1968). The technology of teaching. New York, NY: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Skinner, B. (1972). Beyond freedom and dignity. New York, NY: Vintage Books.

Soon, C. S., Brass, M., Heinze, H.-J., & Haynes, J.-D. (2008). Unconscious determinants of free decisions in the human brain. Nature Neuroscience, 11(5), 543–545.

Tooby, J., & Cosmides, L. (1992). The psychological foundations of culture. In J. H. Barkow & L. Cosmides (Eds.), The adapted mind: Evolutionary psychology and the generation of culture (p. 666). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Watson, J. B., & Rayner, R. (1920). Conditioned emotional reactions. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 3(1), 1–14.

Wegner, D. M. (2002). The illusion of conscious will. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Wegner, D. M. (2003). The mind’s best trick: How we experience conscious will. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 7(2), 65–69.

Yang, Y.-J., & Chiu, C.-Y. (2009). Mapping the structure and dynamics of psychological knowledge: Forty years of APA journal citations (1970–2009). Review of General Psychology, 13(4), 349–356.

Image Attributions

Figure 1.2: https://twitter.com/sureteduquebec/status/353519189769732096/photo/1

Figure 1.3: Plato photo (http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Platon2.jpg.) courtesy of Bust of Aristotle by Giovanni Dall’Orto, (http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Busto_di_Aristotele_conservato_a_Palazzo_Altaemps, _Roma._Foto_di_Giovanni_Dall%27Orto.jpg) used under CC BY license.

Figure 1.4: Wundt research group by Kenosis, (http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Wundt-research-group.jpg) is in the public domain; Edward B. Titchener (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Edward_B._Titchener.jpg) is in the public domain.

Figure 1.5: William James (http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:William_James,_philosopher.jpg). Charles Darwin by George Richmond (http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Charles_Darwin_by_G._Richmond.jpg) is in public domain.

Figure 1.6: Sigmund Freud by Max Halberstadt (http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sigmund_Freud_LIFE.jpg) is in public domain.

Figure 1.7: B.F. Skinner at Harvard circa 1950 (http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:B.F._Skinner_at_Harvard_circa _1950.jpg) used under CC BY 3.0 license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/deed.en).

Figure 1.8: “West Wittering Wonderful As Always” by Gareth Williams (http://www.flickr.com/photos/gareth1953/7976359044/) is licensed under CC BY 2.0. “Family playing a board game” by Bill Branson (http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Family_playing_a_board_game_(3).jpg) is in public domain.