1.1 The Macroeconomy

A Brief introduction to personal finance

Personal Finance[1]

The circumstances or characteristics of your life influence your financial concerns and plans. What you want and need—and how and to what extent you want to protect the satisfaction of your wants and needs—all depend on how you live and how you’d like to live in the future. While everyone is different, there are common circumstances of life that affect personal financial concerns and thus affect everyone’s financial planning. Factors that affect personal financial concerns are family structure, health, career choices, and age.

Family Structure

Marital status and dependents, such as children, parents, or siblings, determine whether you are planning only for yourself or for others as well. If you have a spouse or dependents, you have a financial responsibility to someone else, and that includes a responsibility to include them in your financial thinking. You may expect the dependence of a family member to end at some point, as with children or elderly parents, or you may have lifelong responsibilities to and for another person.

Partners and dependents affect your financial planning as you seek to provide for them, such as paying for children’s education. Parents typically want to protect or improve the quality of life for their children and may choose to limit their own fulfillment to achieve that end.

Providing for others increases income needs. Being responsible for others also affects your attitudes toward and tolerance of risk. Typically, both the willingness and ability to assume risk diminishes with dependents, and a desire for more financial protection grows. People often seek protection for their income or assets even past their own lifetimes to ensure the continued well-being of partners and dependents. An example is a life insurance policy naming a spouse or dependents as beneficiaries.

Health

Your health is another defining circumstance that will affect your expected income needs and risk tolerance and thus your personal financial planning. Personal financial planning should include some protection against the risk of chronic illness, accident, or long-term disability and some provision for short-term events, such as pregnancy and birth. If your health limits your earnings or ability to work or adds significantly to your expenditures, your income needs may increase. The need to protect yourself against further limitations or increased costs may also increase. At the same time your tolerance for risk may decrease, further affecting your financial decisions.

Career Choice

Your career choices affect your financial planning, especially through educational requirements, income potential, and characteristics of the occupation or profession you choose. Careers have different hours, pay, benefits, risk factors, and patterns of advancement over time. Thus, your financial planning will reflect the realities of being a postal worker, professional athlete, commissioned sales representative, corporate lawyer, freelance photographer, librarian, building contractor, tax preparer, professor, Web site designer, and so on. For example, the careers of most athletes end before middle age, have higher risk of injury, and command steady, higher-than-average incomes, while the careers of most sales representatives last longer with greater risk of unpredictable income fluctuations.

Most people begin their independent financial lives by selling their labor to create an income by working. Over time they may choose to change careers, develop additional sources of concurrent income, move between employment and self-employment, or become unemployed or reemployed. Along with career choices, all these changes affect personal financial management and planning.

Age

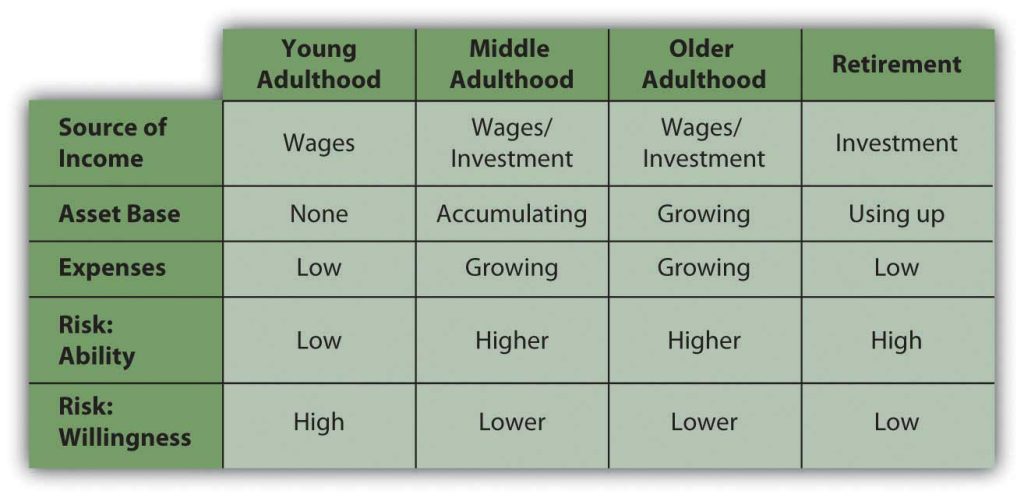

Needs, desires, values, and priorities all change over a lifetime, and financial concerns change accordingly. Ideally, personal finance is a process of management and planning that anticipates or keeps abreast with changes. Although everyone is different, some financial concerns are common to or typical of the different stages of adult life. Analysis of life stages is part of financial planning.

At the beginning of your adult life, you are more likely to have no dependents, little if any accumulated wealth, and few assets. (Assets are resources that can be used to create income, decrease expenses, or store wealth as an investment.) As a young adult you also are likely to have comparatively small income needs, especially if you are providing only for yourself. Your employment income is probably your primary or sole source of income. Having no one and almost nothing to protect, your willingness to assume risk is usually high. At this point in your life, you are focused on developing your career and increasing your earned income. Any investments you may have are geared toward growth.

As your career progresses, income increases but so does spending. Lifestyle expectations increase. If you now have a spouse and dependents and elderly parents to look after, you have additional needs to manage. In middle adulthood you may also be acquiring more assets, such as a house, a retirement account, or an inheritance.

As income, spending, and asset base grow, ability to assume risk grows, but willingness to do so typically decreases. Now you have things that need protection: dependents and assets. As you age, you realize that you require more protection. You may want to stop working one day, or you may suffer a decline in health. As an older adult you may want to create alternative sources of income, perhaps a retirement fund, as insurance against a loss of employment or income. Figure 1.1.1 suggests the effects of life stages on financial decision making.

Early and middle adulthoods are periods of building up: building a family, building a career, increasing earned income, and accumulating assets. Spending needs increase, but so do investments and alternative sources of income.

Later adulthood is a period of spending down. There is less reliance on earned income and more on the accumulated wealth of assets and investments. You are likely to be without dependents, as your children have grown up or your parents passed on, and so without the responsibility of providing for them, your expenses are lower. You are likely to have more leisure time, especially after retirement.

Without dependents, spending needs decrease. On the other hand, you may feel free to finally indulge in those things that you’ve “always wanted.” There are no longer dependents to protect, but assets demand even more protection as, without employment, they are your only source of income. Typically, your ability to assume risk is high because of your accumulated assets, but your willingness to assume risk is low, as you are now dependent on those assets for income. As a result, risk tolerance decreases: you are less concerned with increasing wealth than you are with protecting it.

Effective financial planning depends largely on an awareness of how your current and future stages in life may influence your financial decisions.

Khan Academy: Easy Tips to Save Money Every Day

The Macroeconomy[2]

Financial planning has to take into account conditions in the wider economy and in the markets that make up the economy. The labor market, for example, is where labor is traded through hiring or employment. Workers compete for jobs and employers compete for workers. In the capital market, capital (cash or assets) is traded, most commonly in the form of stocks and bonds (along with other ways to package capital). In the credit market, a part of the capital market, capital is loaned and borrowed rather than bought and sold. These and other markets exist in a dynamic economic environment, and those environmental realities are part of sound financial planning.

In the long term, history has proven that an economy can grow over time, that investments can earn returns, and that the value of currency can remain relatively stable. In the short term, however, that is not continuously true. Contrary or unsettled periods can upset financial plans, especially if they last long enough or happen at just the wrong time in your life. Understanding large-scale economic patterns and factors that indicate the health of an economy can help you make better financial decisions. These systemic factors include, for example, business cycles and employment rates.

Business Cycles

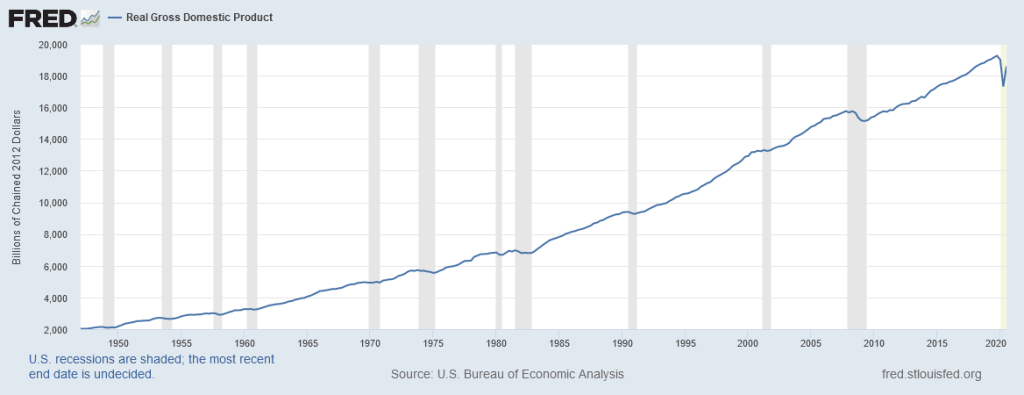

An economy tends to be productive enough to provide for the wants of its members. Normally, economic output increases as population increases or as people’s expectations grow. An economy’s output or productivity is measured by its gross domestic product or GDP, the value of what is produced in a period. When the GDP is increasing, the economy is in an expansion, and when it is decreasing, the economy is in a contraction. An economy that contracts for half a year is said to be in recession; a prolonged recession is a depression. The GDP is a closely watched barometer of the economy. The GDP since 1947 is shown in Figure 1.1.2 below.

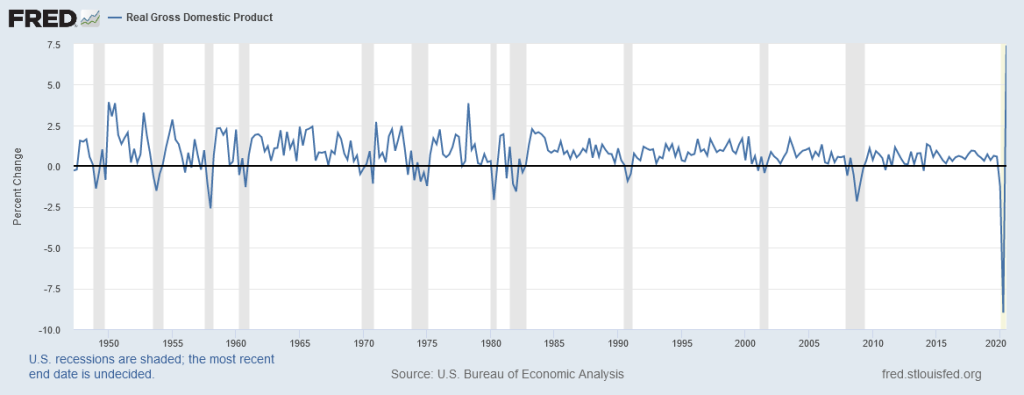

Over time, the economy tends to be cyclical, usually expanding but sometimes contracting. This is called the business cycle. Periods of contraction are generally seen as market corrections, or the market regaining its equilibrium, after periods of growth. Growth is never perfectly smooth, so sometimes certain markets become unbalanced and need to correct themselves. Over time, the periods of contraction seem to have become less frequent, as you can see in Figure 1.1.3, the growth rate of the real GDP fluctuates from one year to the next. The business cycles still occur nevertheless.

There are many metaphors to describe the cyclical nature of market economies: “peaks and troughs,” “boom and bust,” “growth and contraction,” “expansion and correction,” and so on. While each cycle is born in a unique combination of circumstances, cycles occur because things change and upset economic equilibrium. That is, events change the balance between supply and demand in the economy overall. Sometimes demand grows too fast and supply can’t keep up, and sometimes supply grows too fast for demand. There are many reasons that this could happen, but whatever the reasons, buyers and sellers react to this imbalance, which then creates a change.

One Minute Economics: The Gross Domestic Product and Government Revenue Explained (all rights reserved)

Employment

An economy produces not just goods and services to satisfy its members but also jobs, because most people participate in the market economy by trading their labor, and most rely on wages as their primary source of income. The economy therefore must provide opportunity to earn wages so more people can participate in the economy through the market. Otherwise, more people must be provided for in some other way, such as a private or public subsidy (charity or welfare).

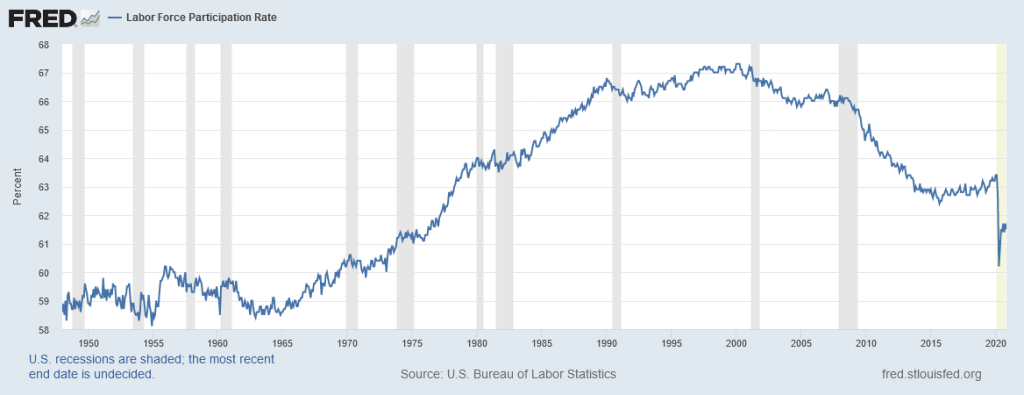

The unemployment rate is a measure of an economy’s shortcomings, because it shows the proportion of people who want to work but don’t because the economy cannot provide them jobs. There is always some so-called natural rate of unemployment as people move in and out of the workforce as the circumstances of their lives change—for example, as they retrain for a new career or take time out for family. But natural unemployment should be consistently low and not affect the productivity of the economy. Figure 1.1.4 shows the unemployment rate in the United States since 1947.

Unemployment also shows that the economy is not efficient, because it is not able to put all its productive human resources to work.

The labor force participation rate shows how successful an economy is at creating opportunities to sell labor and efficiently using its human resources. A healthy market economy uses its labor productively, is productive, and provides employment opportunities as well as consumer satisfaction through its markets. This is shown below in Figure 1.1.5.

At either end of this scale of growth, the economy is in an unsustainable position: either growing too fast, with too much demand for labor, or shrinking, with too little demand for labor.

If there is too much demand for labor—more jobs than workers to fill them—then wages will rise, pushing up the cost of everything and causing prices to rise. Prices usually rise faster than wages, for many reasons, which would discourage consumption that would eventually discourage production and cause the economy to slow down from its “boom” condition into a more manageable rate of growth.

If there is too little demand for labor—more workers than jobs—then wages will fall or, more typically, there will be people without jobs, or unemployment. If wages become low enough, employers theoretically will be encouraged to hire more labor, which would bring employment levels back up. However, it doesn’t always work that way, because people have job mobility—they are willing and able to move between economies to seek employment.

If unemployment is high and prolonged, then too many people are without wages for too long, and they are not able to participate in the economy because they have nothing to trade. In that case, the market economy is just not working for too many people, and they will eventually demand a change (which is how most revolutions have started).

One Minute Economics: The Unemployment Rate and the Labor Force Participation Rate Compared (all rights reserved)

Other Indicators of Economic Health

Other economic indicators give us clues as to how “successful” our economy is, how well it is growing, or how well positioned it is for future growth. These indicators include statistics, such as the number of houses being built or existing home sales, orders for durable goods (e.g., appliances and automobiles), consumer confidence, producer prices, and so on. However, GDP growth and unemployment are the two most closely watched indicators, because they get at the heart of what our economy is supposed to accomplish: to provide diverse opportunities for the most people to participate in the economy, to create jobs, and to satisfy the consumption needs of the most people by enabling them to get what they want.

An expanding and healthy economy will offer more choices to participants: more choices for trading labor and for trading capital. It offers more opportunities to earn a return or an income and therefore also offers more diversification and less risk.

Naturally, everyone would rather operate in a healthier economy at all times, but this is not always possible. Financial planning must include planning for the risk that economic factors will affect financial realities. A recession may increase unemployment, lowering the return on labor—wages—or making it harder to anticipate an increase in income. Wage income could be lost altogether. Such temporary involuntary loss of wage income probably will happen to you during your lifetime, as you inevitably will endure economic cycles.

A hedge against lost wages is investment to create other forms of income. In a period of economic contraction, however, the usefulness of capital, and thus its value, may decline as well. Some businesses and industries are considered immune to economic cycles (e.g., public education and health care), but overall, investment returns may suffer. Thus, during your lifetime business cycles will likely affect your participation in the capital markets as well.

Currency Value

Stable currency value is another important indicator of a healthy economy and a critical element in financial planning. Like anything else, the value of a currency is based on its usefulness. We use currency as a medium of exchange, so the value of a currency is based on how it can be used in trade, which in turn is based on what is produced in the economy. If an economy produces little that anyone wants, then its currency has little value relative to other currencies, because there is little use for it in trade. So a currency’s value is an indicator of how productive an economy is.

A currency’s usefulness is based on what it can buy, or its purchasing power. The more a currency can buy, the more useful and valuable it is. When prices rise or when things cost more, purchasing power decreases; the currency buys less and its value decreases.

When the value of a currency decreases, an economy has inflation. Its currency has less value because it is less useful; that is, less can be bought with it. Prices are rising. It takes more units of currency to buy the same amount of goods. When the value of a currency increases, on the other hand, an economy has deflation Prices are falling; the currency is worth more and buys more.

For example, say you can buy five video games for $20. Each game is worth $4, or each dollar buys ¼ of a game. Then we have inflation, and prices—including the price of video games—rise. A year later you want to buy games, but now your $20 only buys two games. Each one costs $10, or each dollar only buys one-tenth of a game. Rising prices have eroded the purchasing power of your dollars.

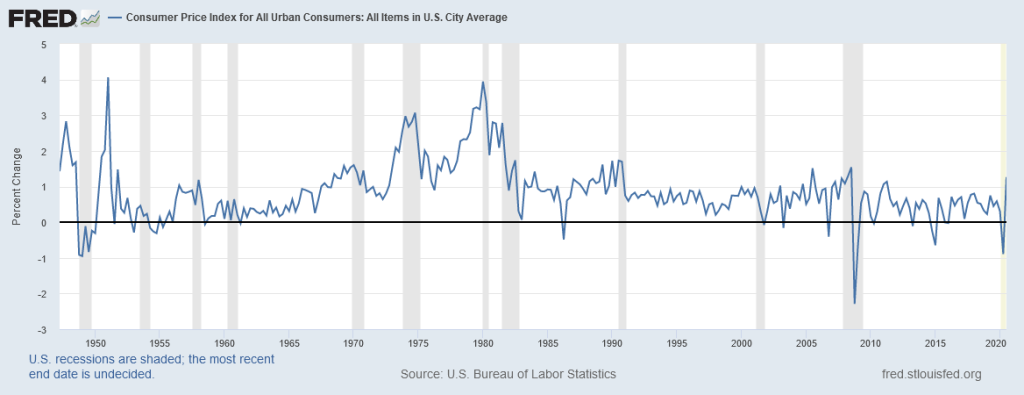

If there is deflation, prices fall, so maybe a year later you could buy ten video games with your same $20. Now each game costs only $2, and each dollar buys half a game. The same amount of currency buys more games: its purchasing power has increased, as has its usefulness and its value. Figure 1.1.6 shows the inflation rate for the United States.

Currency instabilities can also affect investment values, because the dollars that investments return don’t have the same value as the dollars that the investment was expected to return. Say you lend $100 to your sister, who is supposed to pay you back one year from now. There is inflation, so over the next year, the value of the dollar decreases (it buys less as prices rise). Your sister does indeed pay you back on time, but now the $100 that she gives back to you is worth less (because it buys less) than the $100 you gave her. Your investment, although nominally returned, has lost value: you have your $100 back, but you can’t do as much with it; it is less useful.

If the value of currency—the units in which wealth is measured and stored—is unstable, then investment returns are harder to predict. In those circumstances, investment involves more risk. Both inflation and deflation are currency instabilities that are troublesome for an economy and also for the financial planning process. An unstable currency affects the value or purchasing power of income. Price changes affect consumption decisions, and changes in currency value affect investing decisions.

It is human nature to assume that things will stay the same, but financial planning must include the assumption that over a lifetime you will encounter and endure economic cycles. You should try to anticipate the risks of an economic downturn and the possible loss of wage income and/or investment income. At the same time, you should not assume or rely on the windfalls of an economic expansion.

One Minute Economics: Inflation Explained in One Minute.

- Adapted from 1.1 Individual or “Micro” Factors That Affect Financial Thinking in Personal Finance by Lumen learning. CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- Adapted from 1.2 Systemic or “Macro” Factors That Affect Financial Thinking in Personal Finance by Lumen Learning shared under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license. ↵

Periods of a person’s life based on age and personal circumstances that reflect different needs, goals, and financial capabilities.

Resources that can be used to create future economic benefit, such as increasing income, decreasing expenses, or storing wealth as an investment.

Where labor is traded through hiring or employment and price is determined by the interaction of employers and employees.

A market where long-term liquidity is traded.

A part of the capital market where capital is lent and borrowed through the trading of debt securities such as bonds.

The total value of all final goods and services produced in a year in a nation’s economy. It is used as a fundamental measure of an economy’s growth based on its ability to use resources productively and provide for its members.

A period of economic contraction lasting at least six consecutive months or two consecutive quarters.

A prolonged and severe recession.

Recurring periods of economy-wide expansion, when the economy is growing, and contraction, when the economy is shrinking. Cycles are often measured by the increase or decrease in the GDP.

A measure of the percentage of people in the labor force who are unemployed, that is, those who would like to be working but cannot find a suitable job.

A currency’s usefulness and thus its value as measured by how much it can buy, that is, the quantity of goods and services that can be purchased with one unit of currency.

Period characterized by rising prices, declining purchasing power, and lower currency values (one unit of currency is worth less because it buys a smaller quantity of goods and services).

Period characterized by falling prices, increasing purchasing power, and higher currency values (one unit of currency is worth more because it buys a greater quantity of goods and services).