2.1 Introduction

In this section we will explore the different types of debt. We will be using the present value annuity calculations a lot so if you are unsure of how those work, be sure to work through the practice problems or come talk to me!

While we will explore different types of debt soon, let us first consider two concepts first: your credit score and debt repayment.

Credit Scores[1]

A credit score is a numerical expression based on a level analysis of a person’s credit files, to represent the creditworthiness of an individual. A credit score is primarily based on a credit report, information typically sourced from credit bureaus.

Lenders, such as banks and credit card companies, use credit scores to evaluate the potential risk posed by lending money to consumers and to mitigate losses due to bad debt. Lenders use credit scores to determine who qualifies for a loan, at what interest rate, and what credit limits. Lenders also use credit scores to determine which customers are likely to bring in the most revenue. The use of credit or identity scoring prior to authorizing access or granting credit is an implementation of a trusted system.

Credit scoring is not limited to banks. Other organizations, such as mobile phone companies, insurance companies, landlords, and government departments employ the same techniques. Digital finance companies such as online lenders also use alternative data sources to calculate the creditworthiness of borrowers.

In the United States, a credit score is a number based on a statistical analysis of a person’s credit files, that in theory represents the creditworthiness of that person, which is the likelihood that people will pay their bills. A credit score is primarily based on credit report information, typically from one of the three major credit bureaus: Experian, TransUnion, and Equifax. Income and employment history (or lack thereof) are not considered by the major credit bureaus when calculating credit scores.

There are different methods of calculating credit scores. FICO scores, the most widely used type of credit score, is a credit score developed by FICO, previously known as Fair Isaac Corporation. As of 2018, there were 29 different versions of FICO scores in use in the United States. Some of these versions are “industry specific” scores, that is, scores produced for particular market segments, including automotive lending and bankcard (credit card) lending. Industry-specific FICO scores produced for automotive lending are formulated differently than FICO scores produced for bankcard lending. Nearly every consumer will have different FICO scores depending upon which type of FICO score is ordered by a lender; for example, a consumer with several paid-in-full car loans but no reported credit card payment history will generally score better on a FICO automotive-enhanced score than on a FICO bankcard-enhanced score. FICO also produces several “general purpose” scores which are not tailored to any particular industry. Industry-specific FICO scores range from 250 to 900, whereas general purpose scores range from 300 to 850.

FICO scores are used by many mortgage lenders that use a risk-based system to determine the possibility that the borrower may default on financial obligations to the mortgage lender.

Usage of credit histories in employment screenings increased from 19% in 1996 to 42% in 2006.[30]:1 However, credit reports for employment screening purposes do not include credit scores.[30]:2

Americans are entitled to one free credit report in every 12-month period from each of the three credit bureaus, but are not entitled to receive a free credit score. The three credit bureaus run Annualcreditreport.com, where users can get their free credit reports. Credit scores are available as an add-on feature of the report for a fee. If the consumer disputes an item on a credit report obtained using the free system, under the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA), the credit bureaus have 45 days to investigate, rather than 30 days for reports obtained otherwise.

Under the Fair Credit Reporting Act, a consumer is entitled to a free credit report (but not a free credit score) within 60 days of any adverse action (e.g., being denied credit, or receiving substandard credit terms from a lender) taken as a result of their credit score. Under the Wall Street reform bill passed on 22 July 2010, a consumer is entitled to receive a free credit score if they are denied a loan or insurance due to their credit score.[32]

The generic or classic or general-purpose FICO credit score ranges between 300 and 850. The VantageScore 3.0 score and VantageScore 4.0 score range from 300–850.

In the United States, the median generic FICO score was 723 in 2006[33] and 711 in 2011.[34] The performance definition of the FICO risk score (its stated design objective) is to predict the likelihood that a consumer will go 90 days past due or worse in the subsequent 24 months after the score has been calculated. The higher the consumer’s score, the less likely he or she will go 90 days past due in the subsequent 24 months after the score has been calculated. Because different lending uses (mortgage, automobile, credit card) have different parameters, FICO algorithms are adjusted according to the predictability of that use. For this reason, a person might have a higher credit score for a revolving credit card debt when compared to a mortgage credit score taken at the same point in time.

The interpretation of a credit score will vary by lender, industry, and the economy as a whole. While 640 has been a divider between “prime” and “subprime”, all considerations about score revolve around the strength of the economy in general and investors’ appetites for risk in providing the funding for borrowers in particular when the score is evaluated. In 2010, the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) tightened its guidelines regarding credit scores to a small degree, but lenders who have to service and sell the securities packaged for sale into the secondary market largely raised their minimum score to 640 in the absence of strong compensating factors in the borrower’s loan profile. In another housing example, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac began charging extra for loans over 75% of the value that have scores below 740. Furthermore, private mortgage insurance companies will not even provide mortgage insurance for borrowers with scores below 660. Therefore, “prime” is a product of the lender’s appetite for the risk profile of the borrower at the time that the borrower is asking for the loan.

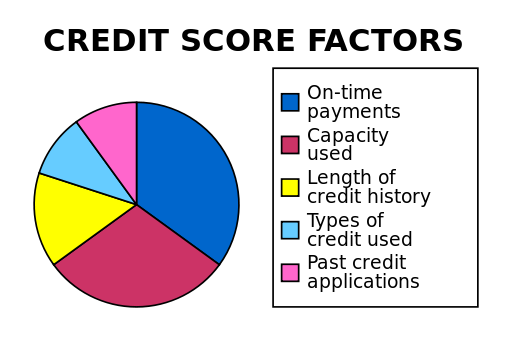

Several factors affect individual’s credit scores. One factor is the amount an individual borrowed as compared to the amount of credit available to the individual. As an individual borrows, or leverages, more money, the individual’s credit score decreases.

Money Coach: Credit Scores and Reports 101 (all rights reserved)

Debt repayment

As a quick note before we dig-in. You will see a variety of interest rate terms like effective interest rate, APY, and APR. These are all essentially the same thing and for the purpose of our class we will treat as the same. Each of these three terms essentially looks at the true interest rate over the year when you include the concept of compounding periods. The simplest interest to calculate is when interest compounds annually, but there are very few situations where that occurs. Typically financial instruments compounds monthly or daily. So as we should remember, the effective interest rate gives you the interest rate if the interest were to compound annually. So, if you have a credit card with a 30% interest rate that compounds daily, your effective interest rate is actually closer to 35% since interest charges are added daily.

Debt Snowball Method[2]

The debt-snowball method is a debt-reduction strategy, whereby one who owes on more than one account pays off the accounts starting with the smallest balances first, while paying the minimum payment on larger debts. Once the smallest debt is paid off, one proceeds to the next larger debt, and so forth, proceeding to the largest ones last.[1] This method is sometimes contrasted with the debt stacking method, also called the “debt avalanche method”, where one pays off accounts on the highest interest rate first.[2][3]

The debt-snowball method is most often applied to repaying revolving credit – such as credit cards. Under the method, extra cash is dedicated to paying debts with the smallest amount owed.[4]

The basic steps in the debt snowball method are as follows:

- List all debts in ascending order from smallest balance to largest. This is the method’s most distinctive feature, in that the order is determined by amount owed, not the rate of interest charged. However, if two debts are very close in amount owed, then the debt with the higher interest rate would be moved above in the list.

- Commit to pay the minimum payment on every debt.

- Determine how much extra can be applied towards the smallest debt.

- Pay the minimum payment plus the extra amount towards that smallest debt until it is paid off. Note that some lenders (mortgage lenders, car companies) will apply extra amounts towards the next payment; in order for the method to work the lenders need to be contacted and told that extra payments are to go directly toward principal reduction. Credit cards usually apply the whole payment during the current cycle.

- Once a debt is paid in full, add the old minimum payment (plus any extra amount available) from the first debt to the minimum payment on the second smallest debt, and apply the new sum to repaying the second smallest debt.

- Repeat until all debts are paid in full.

In theory, by the time the final debts are reached, the extra amount paid toward the larger debts will grow quickly, similar to a snowball rolling downhill gathering more snow, hence the name.

The theory appeals to human psychology: by paying the smaller debts first, the individual, couple, or family sees fewer bills as more individual debts are paid off, thus giving ongoing positive feedback on their progress towards eliminating their debt.

In situations where a debt has both a higher interest rate and higher balance than another debt, the debt-snowball method will prioritize the smaller debt even though paying the larger debt would be more cost-effective. Several writers and researchers have considered this contradiction between the method and a strictly mathematical approach. Writing in Forbes, Rob Berger noted that “humans aren’t really rational creatures” and stresses that research tends to support the debt snowball method in real-world scenarios.[5] The primary benefit of the smallest-balance plan is the psychological benefit of seeing results sooner, in that the debtor sees reductions in both the number of creditors owed (and, thus, the number of bills received) and the amounts owed to each creditor. In a 2012 study by Northwestern’s Kellogg School of Management, researchers found that “consumers who tackle small balances first are likelier to eliminate their overall debt” than trying to pay off high interest rate balances first.[6] A 2016 study in Harvard Business Review came to a similar conclusion:

We tested a variety of hypotheses and ultimately determined that it is not the size of the repayment or how little is left on a card after a payment that has the biggest impact on people’s perception of progress; rather it’s what portion of the balance they succeed in paying off. Thus focusing on paying down the account with the smallest balance tends to have the most powerful effect on people’s sense of progress – and therefore their motivation to continue paying down their debts.[7]

Author and radio host Dave Ramsey, a proponent of the debt-snowball method, concedes that an analysis of math and interest leans toward paying the highest interest debt first. However, based on his experience, Ramsey states that personal finance is “20 percent head knowledge and 80 percent behavior” and he argues that people trying to reduce debt need “quick wins” (i.e., paying off the smallest debt) in order to remain motivated toward debt reduction.[8]

Debt stacking method[3]

Note: Debt stacking is also referred to as the debt avalanche method and the high rate method.

The debt stacking method (also known as the debt avalanche method) recommends that you make a list of all your debts, ranked by interest rate, from highest to lowest.

For example, you might owe:

- Mastercard, $2,500—19%, highest interest rate

- Visa, $7,500—13%, second-highest interest rate

- Car loan, $4,000—8%, third-highest interest rate

- Student loan, $1,900—5%, lowest interest rate

The debt stacking method advises that you make the minimum payment on all your loans. Then, you should throw all of your extra money toward paying off your Mastercard, which has the highest interest rate, at 19%.

Once you’ve wiped away your Mastercard debt, tackle the Visa balance, which has the second-highest interest rate, at 13%.

It’ll take you a long time to repay the Visa, since it has the highest balance, at $7,500. Stick with it. Whenever you’re done, you can start paying off the debts with lower interest rates.

You may feel frustrated after investing so much time and energy toward paying down a loan without feeling the mental victory of crossing it off your list.

Next Level Life: Debt Snowball versus Debt Avalanche (all rights reserved)