16 A Culture of Violence and Silence in Remote Canada: Impacts on Service Delivery to Address Intimate Partner Violence

Heather Fikowski and Pertice Moffitt

Intimate partner violence (IPV) in Northern Canada is a major public health issue that continues to impact women, families and communities and consistently demonstrates the highest rates in the country. A five-year mixed-methods study conducted between 2011 and 2017 investigated the community and frontline response to IPV in the Northwest Territories. Several dominant themes emerged that facilitated frontline worker’s sense of having their “hands tied” when trying to support women who are experiencing violence in their intimate relationships. The culture of violence and silence was identified as a theme pivotal in maintaining the social process of women “shutting up about the violence”. This chapter will explore the culture of violence and silence by considering how this increases women’s vulnerability and susceptibility to IPV as well as the negative impacts to effective frontline service delivery. Factors that will be specifically explored include: historical trauma, violence normalized, gossip as a tool for silence, community retribution, family and community values and self-preservation.

Key Terms: Aboriginal, Indigenous, intimate partner violence, abuse, northern, remote, Canada

Introduction

Violence rates are demonstratively higher amongst Indigenous women, as compared to non-Indigenous women in Canada (Brownridge, 2008). Researchers have also acknowledged that impacts of colonization and oppression contribute to Indigenous people’s understanding of violence and its higher prevalence rates within these communities (Brownridge, 2003; Daoud, Smylie, Urquia, Allan & O’Campo, 2013; Wendt & Hornosty, 2010). Canada’s long history of colonial policies, such as residential schooling, has resulted in intergenerational impacts of historical trauma for Indigenous peoples (Daoud et al., 2013). These structural experiences of oppression continue to demonstrate themselves in social issues, such as substance use, poverty, housing and the over-representation of Indigenous children in the child welfare system (Blackstock & Tromé, 2005). The impacts of this leads to Indigenous people’s increased risk for poorer health and social problems, including intimate partner violence (IPV) (Bombay, Matheson, & Anisman, 2014). This chapter will focus on a particular construct that contributes to sustained higher rates of IPV in northern Canada, as well as hinders efforts of frontline service workers to support women who are surviving it.

Literature Review

A socially constructed culture of violence and silence has been acknowledged as a factor that shapes women’s experiences of violence in rural, remote and/or Indigenous communities (Campbell, 2007; Kuokkanen, 2015; McGillivray & Commaskey, 1999; Shepherd, 2001). This culture has been informally sanctioned belief around violence creates a community context in which children are socialized and women’s susceptibility and vulnerability to violence is heightened. For example, McGillivray and Comaskey (1999) described the experiences of IPV with Indigenous women in rural Canada and found the normalization of violence to be widely reported across the lifespan. They noted this belief as a barrier to women trying to leave the relationship and as a barrier for those responding to violence, suggesting it exists relationally and at a community level.

Challenging this culturally constructed belief can possibly lead to community shaming or disapproval, banishment or repercussions from the perpetrator and his family and community allies (McGillivray & Comaskey, 1999; Wendt & Horonsty, 2010). In addition to this, women who experience violence also report societal pressure and values of maintaining the family. Additionally, the perpetrator’s social status within the community (Wendt & Hornosty, 2010); a lack of privacy or anonymity as well as perceived lack of confidentiality has also been found to keep women silent in coming forward or seeking help to leave a violent relationship (Hughes, 2010; Shephard, 2001; Wendt & Hornosty, 2010; Wuerch, Zorn, Juschka, & Hampton, 2016). All of these factors pose unique and additional challenges to those already in existence for women who survive controlling, abusive intimate relationships.

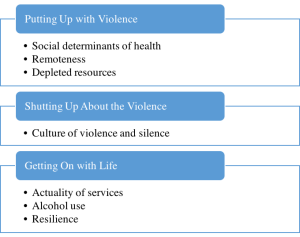

A recent mixed-methods study conducted in northern Canada revealed IPV occurrences in every community, many of which are void of or sparsely supported by formal services to help women experiencing violence (Moffitt & Fikowski, 2017). Additionally, the geographic region of this study identified multiple communities with little to no road access. These remotely located communities were described as predominantly Indigenous with support provided by the larger regional centers which had greater populations of non-Indigenous residents. Findings indicated that frontline workers’ hands were tied in efforts to support women and families as well as moving communities towards nonviolence. Three social processes described the context of this central problem: women are putting up with violence, shutting up about the violence and getting on with life. Details of the overall findings are listed in Table 1.

Table 1 – Thematic Description of NWT Community Response to IPV: “Hands Are Tied”

This chapter will describe the culture of violence and silence as a contributing factor that uniquely intersects with remoteness, high rates of alcohol use, depleted resources, compromised social determinants of health, the actuality of frontline service provision, and resilience to sustain violence within communities across the Northwest Territories (NWT).

Methods

Data for this chapter was obtained from research conducted between 2010-1016 in the NWT of Canada. This was one of four jurisdictions seeking to understand the community response to IPV in rural and northern regions of Canada. The larger project team met annually to share findings and collaborate in moving forward with the next phases of data collection. These meetings and the project itself was continuously under the guidance of an Indigenous Elder who oversaw the larger project spanning all four jurisdictions Annually, ethics approval was provided by the University of Regina and scientific license awarded from the Aurora Research Institute.

In the first year of the study, data was gathered from the RCMP national database and an environmental scan of family violence resources across the NWT. This data was used with Geographic Information Systems techniques to produce several GIS maps that more tangibly visualize the resources available and IPV incidents across the NWT. These GIS maps helped indicate where data collection would occur in the second year of the project. In the second and third year of the study, 56 semi-structured interviews were completed face-to-face or over the telephone as well as a focus group in each of two communities; participants were frontline service providers working in the field of family violence. Participants were recruited by purposeful sampling and represented 12 NWT communities (35% of communities); the sample included police officers (RCMP members), shelter workers, victim services workers, nurses and other health care professionals, counsellors and social workers. Geographic Information Systems (GIS) maps, grounded theory and constant comparative method were used within a feminist philosophy to analyze the data which occurred concurrently with data collection. Interview transcripts were analyzed individually using line by line coding, and then would meet to share the analyses, collaborating to produce a preliminary model after the second year. Similar processes were used in the third year of data collection, presenting the preliminary model to participants for validation. The final years of the study comprised largely of the development of an action plan and knowledge translation.

Findings

Within the broad theme of a culture of violence and silence, six sub-themes were identified in the analysis: historical trauma, violence normalized, gossip as a tool for silence, community retribution, family and community values, and self-preservation. As one participant described a remote community of the NWT, “I call it the community of secrets, they really never talk about anything.” (Community Health Nurse 13). Though each of these sub-themes will be discussed separately, they quite often were presented as a unique and complex web of intersecting variables that support each other in a way that maintains the social construct of violence and silence, and in turn the ongoing presence of IPV. None are more significant than others, but are uniquely multidimensional in the way women experience violence within their relationship and community. One participant demonstrated the nature of this intersectionality:

I think it’s more normalized than I would like it to be. Yeah, I think with the heritage with residential schools and people suffering traumatic injury there and that pain being handed down generationally. I think there’s been generations of people putting up with a lot and a lot of acting out. And I think that goes to the blaming I was talking about before. If a woman gets hit and files a police report, the people around her might be blaming her because as far as they’re concerned, ‘you don’t do that. You don’t go calling the police.’ It’s more normalized. (Shelter Worker 30)

This notion of intersectionality and unique web of intersecting factors was confirmed by participants throughout our study as we presented this concept to them for validation and as well, in our community presentations across the NWT.

Historical Trauma

Participants acknowledged IPV as an issue arising from historical trauma. They also discussed it reflected in the experience of violence as one that occurs across the lifespan. One participant explained:

I really think that in the north, it goes way beyond partner violence. It’s like a family kind of violence. You know, when we do sharing circles with women in communities, the violence is not just from partners. It’s from uncles, brothers, community members. Like the violence comes from all sides…A lot of the stories of violence with the women start when they’re very small. It’s not just partner violence. It starts when they’re little. So, it could be a family member, it could be a community member. The violence starts sometimes as early as age two or three. (Community Development Worker 21)

Participants were aware of the country’s colonial history, including residential schooling. They described the impacts historical trauma has and the effects upon an Indigenous person’s functioning and overall well-being:

It’s almost DNA implanted through the generations. Right through the alcohol abuse, the drug abuse, the residential school process. We have lost generations of parenting skills. And I’m an Aboriginal person…I’ve lived it. It’s been in my family. I’ve witnessed it and that’s why I’m a police officer today ‘cause they were always at my door helping my mother when she was abused. And you know what, I can honest to God say that it’s almost like DNA implanted in our people. I’m not saying all our people, but you know what, as Aboriginal people, we suffer a high volume of domestic violence. We can’t hide the numbers. You can’t sit there and say ‘well, you know, we’re spiritual’. Well, yeah, but at the end of the day we suffer a high percentage of it in our families and communities as a whole. And we suffer as a whole as a people because of that. Because that’s not the traditional way, where our people come from, or the culture and protocols that are attached to our different societies. (RCMP Member 23)

This was confirmed by another participant who suggested a community member’s struggle to regulate his emotions, even with helpful strategies to manage them:

I had a young guy come in who was actually quite a violent young fella and I was trying to do some counselling and, for some reason, he connected with me. He was saying how his father was incredibly abusive to him. His father tried to choke him, and so of course he had been putting this onto his wife, what was primarily emotional violence against his wife and children. But he was saying he didn’t understand. He was saying, ‘I work out, I eat well.’ He said, “I work hard. I try to do things. And still inside I always feel anxious and revved up.’ (Community Health Nurse 10).

Another impact of historical trauma comes from people’s understanding of frontline service workers, such as RCMP and social workers. They described resistance or hesitation from community people to access their help as well as a general lack of trust with formal service providers. One participant noted:

I think that the process of understanding and healing the legacy of colonization from residential schools is really important in our community as part of healing lateral violence. I mean, it’s a major, major divider and a cause of a really prevalent lack of trust that permeates our culture which makes any type of programming very difficult to get a positive outcome when there is that kind of foundation of a lack of trust. (Victim Services Worker 09).

Community healing is an important component to a shift towards nonviolence. They also noted ways in which this can be supported by frontline workers when working directly with people who might be experiencing the impacts of historical trauma. One participant suggested:

I really think looking at why does social suffering still continue and how past trauma and residential schools play into that. And I think that’s a dialogue that is started a little but I think for a lot of people, it’s the attitude of ‘oh my goodness, it happened so long ago, and why are they still complaining about that? Move on and get over it.’ But it’s like, these are things you can’t get over, this is something you take with you to the grave, and giving people that space, the people who went into those schools and experience that trauma to say ‘this is why you’re feeling like this and this is why it’s hard for you to parent’, and having that understanding. I think doing that at a community level would be really good. (Victim Services Worker 20).

Violence Normalized

Violence as an accepted reality amongst women, children, families, and communities was noted by most participants. They emphasized that this significantly contributes to the difficulties in providing services for women experiencing violence. One participant explained:

I think the message that women are getting is this is normalized; ‘this is my life, at least it’s not as bad as my neighbours’. You know, this is the normalization of violence. So I think it’s a really lonely journey for women…There’s a lot of shame, you know. Victims feel embarrassment and shame in having to get service providers involved…So you’ve done nothing wrong, you don’t deserve the violence but you’re being violated, and then we have this understanding; it’s so normalized that people don’t even feel like they deserve full services. It’s kind of like, you made your bed now lie in it, and this is the way it is. (Victim Services Worker 20)

One way to help shift this acceptance is to gently heighten women’s awareness to that sense of normal when they are intervening in a violent crisis using a supportive, nonjudgmental relationship. The importance of early education about healthy relationships was suggested by most participants as another means of creating change in the normalized position of violence:

Because for so long, it’s just been kind of accepted and swept under the rug, and I think now we’re at a pivotal time where, with the education and prevention, and young populations in a lot of our communities, it’s a good time to focus on it. (Social Worker 25)

Other participants highlighted successful change when respected community members role model nonviolence:

Every community has one or two people, if not more [who don’t use violence]. I think if the norm became nonviolence, then I think over time, that maybe more of a common goal, and the violence and abuse would become more the abnormal. Because right now, the norm is violence. (RCMP Member 29).

The notion that rates and severity of violence has become a normal concept across northern communities is two-fold. Participants described the normalization within communities but additionally acknowledged their own desensitization and acceptance of violence rates as frontline service workers. One participant described a notable change in her own understanding about violence and how it occurred with time worked in the north. She purported this changed view towards violence is not conducive to effective support:

We are almost, as service providers and as women, it’s accepted. We’ve become desensitized to it. The victims have become desensitized, so to the service providers…I have extensive victim service experience in [southern Canada] and it is vastly different here [in the north]. There isn’t acceptance [but] that this is a normal occurrence…there’s something wrong with thinking that way. (Victim Services Worker C07)

While frontline workers are acknowledging this more normalized view to the frequency and severity of violence, it remained striking to hear the degree to which they continually emphasized a passion to support women, facilitate change across the north and locate effective responses to create safety for those experiencing violence. Though the desensitization to violence may be a reflection of the impact of the work, it reminds frontline service providers that this dialogue helps to remain conscientious of its abnormality as a way in which to help shift the culture of violence within communities.

Gossip as a Tool for Silence

Gossip within communities was noted by most participants as a powerful tool that keeps women from reaching out to family, friends or service providers. They described how this can stay with a woman and her children for years and that it continues to negatively impact a woman by bringing shame and blame upon her for having spoken out against her violent partner. Gossip, or the threat of gossip, comes from her family, the partner’s family, friends or other community people. From this, she might feel isolated in her experience and without options to reach out for help.

Participants also explained that women might feel threatened by the possibilities of gossip if local people are in frontline positions, such as a community social worker. Regardless of the ethical obligation to maintain a woman’s confidence, participants explained that there is a lack of trust this would be provided:

I’d say people do not want someone [who is in a frontline position] from their own community because there’s this fear that it will be all over town…People just generally feel better, I think, talking to someone not from their own community. (RCMP Member 23)

Other participants explained the benefits of having a mixed staff that includes local people to provide the community perspective, as well as people from out of town so that they can feel safe from their perceptions about the threats of gossip or lack of confidentiality in receiving services from local people. This indicates the importance of acknowledging the possible hesitations, concerns and lack of trust and developing that within the helping relationship when women are accessing services.

Community Retribution

Women who access formal supports when experiencing violence can experience backlash from their family or community members. This retribution can also extend to women’s children and might continue to be experienced for years. Retribution includes such things as harassment, isolation, restricted access to housing or limited employment opportunities within the community. A participant described the experience of retribution like this:

Because in a small community, especially when there is only a couple of main families in the community, she’s basically gonna be banished from the community for going to the police about her husband who beats her up. So she has to move out of the community, or if she stays, then she’s gonna be harassed. It’s never gonna end for her. And then when the victims finally put a stand to it, they can’t handle the pressure from the family members and the community to stay in the relationship. They have no where else to go. So basically, there’s no way out for the victims who are chronically abused. (RCMP Member 06).

These threats of retribution from community people maintaining the silence of women when experiencing violence. To combat this fear, it is important to facilitate supportive relationships amongst community people. One participant suggested:

I think a lot of people in the smallest communities in the NWT, the women are living in isolation and they don’t necessarily have a personal safety network. I think personal safety networks are really important. So that means working with women to learn to feel safe with each other and to trust each other…The best way we found was to get women together on the land, away from their partners and away from all the different stressors of the community. So, on the land was a good way to get women to sort of feel more comfortable, share and talk. (Community Development Worker 28)

Family and Community Values

Another factor that influences women’s decisions to seek help or speak about the violence comes from the value of maintaining the family unit. This may be her own belief, messages delivered directly from others or embedded in covert ways. For example, during our study in one community, Elders insisted a married couple that died in a murder/suicide be buried side by side. One participant described the influential pressure like this:

A lot of the times there’s a couple things that kind of make it difficult for [women]. So, one thing if they’re from [the community], they get a lot of family pressure to return home, because there’s that whole idea of, you know, ‘you’re married and you need to stay in this and you need to work it out’. So they get a lot of that pressure. (Community Health Nurse 13)

Aspects of Indigenous culture also facilitate the (lack of) response women and community people have to men who use violence in their intimate relationships. A participant explained:

But what I would say in general terms is that in some circles within the northern culture, it’s appropriate and expected that the male is gonna be dominant in the family unit and if getting beat up occurred, then it’s part of normal life. Now there’s lots and lots of families that I can think of that don’t buy into that and will not put up with that. But there’s still a significant amount of people that still function in that way of thinking. (RCMP Member 07)

Self-preservation

Women who remain silent in an abusive relationship may be working from a position of self-preservation. They might realize the lack of services available in their community which increases their risks to successfully leave. The severity of abuse experienced by women and thought of leaving under such violent threats might be enough pressure to remain in the relationship. Women are also managing within the experience of a trauma, which might diminish their ability to function or make decisions about leaving. There exists the possible impact of historic trauma, the normalization of violence, threats of gossip and community retribution as well as pressures coming from family to stay in the relationship. In addition, some women experience a lack of understanding from frontline workers when they are resisting violence within their relationship. They can feel judged or blamed from the service providers as well, which also inhibit their willingness to come forward for help. One participant explained:

From my perspective, it looks to me as though family violence or IPV is still perceived largely as a private or domestic matter and not a public concern, not an issue of breaking the law in certain cases and types of violence. I’d say that there is still a lot of stigma attached to accessing services when a woman is experiencing violence. I see women experiencing, not only IPV, but then also a lot of pressure from either the partner’s family or community members, just to kind of keep quiet about what’s going on. And [she’s] seen as a trouble maker if she won’t keep quiet. I see women who resist IPV in the whole spectrum of ways that women resist, from being violent themselves, using verbal attacks, coping through substance abuse, as often being very misunderstood and being perceived by community members, including service providers, as being equally as abusive as opposed to resisting oppressing and trying to preserve their dignity. I’d say that there’s a lot of blaming victims of IPV which I think can also contribute to women staying silent. (Shelter Worker 14)

The other factor that maintains a culture of violence and silence within a community and a woman’s experience when surviving IPV is her willingness to shield the community from adding more indicators of violence that is present amongst the people. She might hesitate in coming forward with charges, seeking help from formal service providers, or reaching out for support from family or friends in an effort to avoid more trauma and violence to what is already occurring or what has been experienced by the community in the past. One participant reported:

I just find that when [women] are at home here and they’re around family, they’re around friends, it’s a small isolated community. Eventually, a true victim will feel as though they’re wronging the rest of the community by going ahead with [the charges]. (RCMP Member 17)

Summary and Implications

These findings describe the frontline experience offering IPV-related services to women in a northern, remote context and under the influence of an embedded culture of violence and silence. Consistently across interviews, participants noted the normalization of violence and the barriers this creates for them to deliver effective services. Participants suggested this possibly surfaces as an effect of historical trauma or as mechanism to manage the current traumas brought on by higher rates of violence in the north. Given this, it is imperative to create educational opportunities that will begin creating a shift in this way of knowing as well as trauma-informed practice approaches when working with women and their families. A majority of participants recommended early educational interventions that focus on healthy relationships as a precursor to that effort. What was also highlighted as a significant action to reach nonviolence in communities was honoring the uniqueness of communities across the north and supporting their own goals and efforts in working towards change.

Several frontline service providers in the study reflected on their understanding about IPV and a noticeable shift where they become desensitized to its frequency and severity. Though only one participant acknowledged the impacts of compassion fatigue (CF) and vicarious trauma (VT), many recounted detailed accounts of traumas they were directly involved in and explained how these have stuck with them. It is important for service providers to ensure they are aware of these risks as a consequence of the work and be able to recognize the signs that it is impacting their professional and/or personal well-being (Mathieu, 2011; McCann & Pearlman, 1990). Both recurring memories and desensitized, normalized attitude towards IPV might be indicators that frontline workers are experiencing the effects of both CF and VT.

Not coming forward was, in part, described as an act of self-preservation; it is an effort to not add any additional challenges to their current life circumstances in the community. The threats and realities of gossip and retribution from community members intimidate women to reach out to service providers as well as family or friends. Frontline workers were also aware of family pressures to remain in the committed relationship, regardless of the violence. These factors also sustain a culture of violence and silence within communities across the NWT. Participants explained it as one way in which their hands are tied in efforts to support women and families. Though there may not be a quick fix to these barriers, there are tangible solutions that frontline workers have found effective. They noted the importance of developing trust within the relationship and a safe space for women to be free from the judgements of either surviving a violent relationship or making efforts to leave it. One participant suggested:

I think we have to provide a lot of education and awareness, a lot of healing programs, a lot of outreach services with people letting them know what resources are available. This model I like to use is ‘there’s never a wrong door’. So when you work with other agencies and support people, there’s always people to help. There’s never a wrong door [because as frontline workers], we’ll direct you or help you and take you to where you should be…We would facilitate that and help them get the resources that they need. (Victim Services Worker 09)

Conclusion

The culture of violence and silence has been found to increase women’s vulnerability to ongoing experiences of IPV and act as a barrier to service provision in northern areas of Canada. The notion of “culture” as described in this chapter relates to a social construction that appears at a personal level and community level. The ongoing violence in communities across the NWT is, in part, sustained by a silenced response from those experiencing it, perpetrating it or aware of its occurrence within the community. What frontline workers described was a somewhat ineffective and disabled response to IPV. That this culture continues to exist and make services more difficult to roll out effectively remains a frustration for workers. However, barriers were met with creative and hopeful directions offered up as a way to continue shifting the current culture towards one that stands up to violence with support.

Additional Resources

Family Violence Initiative: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/health-promotion/stop-family-violence/initiative.html

Organized and led by the Public Health Agency of Canada, this initiative serves as a collaboration with multiple government departments and agencies to address family violence. The website includes information about family violence, trauma-informed approaches to policy and practice resources, ways in which professionals can promote healthy, safe relationships, tools for professionals working with people and communities affected by family violence, and links to possible funding opportunities.

National Aboriginal Circle Against Family Violence: http://nacafv.ca/

This organization focuses on supporting shelters in their efforts to promote safe environments for Indigenous Canadian families. It offers program initiatives for shelter and transition houses that are culturally appropriate as well as networking opportunities for frontline workers, especially those who are in remote locations. It also works to improve public awareness about family violence in Indigenous communities as well as strengthening the relationship and securing funds between all levels of governments, non-governmental organizations and Indigenous partners.

National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health: https://www.ccnsa-nccah.ca/en/

This Canadian national organization supports Indigenous health through research, policy and practice initiatives. Information includes such things as family health across the lifespan and social determinants that impact Indigenous family health. It also includes a two-part series report on historic trauma, explaining Indigenous peoples’ experiences of trauma and oppression as cumulative and intergenerational.

Rural and Northern Response to Intimate Partner Violence: http://www2.uregina.ca/ipv/index.html

This offers a localized space to obtain the details of the research project from which this chapter was based. It provides information about the project’s background, final reports from all four jurisdictions in Canada (Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba and the Northwest Territories) as well as knowledge translation activities in the last several years.

Status of Women Canada: http://www.swc-cfc.gc.ca/index-en.html

The Status of Women Canada aims to promote women’s full participation in Canadian society. Part of their efforts work to end violence against women and girls. It does this by providing policy directives, supporting women’s programs and promoting women’s rights. Their website offers information and strategies to prevent and address gender-based violence as well as other links and resources related to family violence in Canada.

References

Blackstock, C., & Tromé, N. (2005). Community-based child welfare for Aboriginal children: Supporting resilience through structural change. In M. Ungar (Ed.), Handbook for working with children and youth: Pathways to resilience across cultures and contexts (pp. 105-120). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Bombay, A., Matheson, K., & Anisman, H. (2014). The intergenerational effects of Indian Residential Schools: Implications for the concept of historic trauma. Transcultural Psychiatry, 51, 320-338.

Brownridge, D. A. (2003). Male partner violence against Aboriginal women in Canada: An empirical analysis. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 18, 65-83. doi: 10.1177/08862605022385421

Brownridge, D. A. (2008). Understanding the elevated risk of partner violence against Aboriginal women: A comparison of two nationally representative surveys in Canada. Journal of Family Violence, 23, 353-367.

Campbell, K. M. (2007). What was it they lost? Journal of Ethnicity in Criminal Justice, 5, 57 80. doi: 10.1300/J222v05n01_4

Daoud, N., Smylie, J., Urquia, M. Allan, B, & O’Campo, P. (2013). The contribution of socioeconomic position to the excesses of violence and intimate partner violence among Aboriginal versus non-Aboriginal women in Canada. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 104, 278-283.

Hughes, J. (2010). Putting the pieces together: How public health nurses in rural and remote Canadian communities respond to intimate partner violence. Journal of Rural Nursing and Health Care, 10, 34-47.

Kuokkanen, R. (2015). Gendered violence and politics in Indigenous communities. International Feminist Journal of Politics, 17, 271-288. doi: 10.1080/14616742.2014.901816

Mathieu, F. (2011). The compassion fatigue workbook: Creative tools for transforming compassion fatigue and vicarious traumatization. New York, NY: Routledge.

McCann, I. L., & Pearlman, L. A. (1990). Vicarious traumatization: A framework for understanding the psychological effects of working with victims. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 3, 131-149.

McGillivray, A., & Comaskey, B. (1999). Black eyes all of the time: Intimate violence, Aboriginal women and the justice system. Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto Press.

Moffitt, P., & Fikowski, H. (2017). Northwest Territories research project report for territorial stakeholders: Rural and northern community response to intimate partner violence. Yellowknife: Faculties of Nursing and Social Work, Aurora College.

Shepherd, J. (2001). Where do you go when it’s 40 below? Domestic violence among rural Alaska native women. Affilia, 14, 488-510.

Wendt, S., & Hornosty, J. (2010). Understanding contexts of family violence in rural, farming communities: Implications for rural women’s health. Rural Society, 20, 51-63.

Wuerch, M. A., Zorn, K. G., Juschka, D., & Hampton, M. (2016). Responding to intimate partner violence: Challenges faced among service providers in northern communities. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 1-21. doi: 10.1177/0886260516645573

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge that our place of work is on the territory of Chief Drygeese, Treaty 8 and the land of the Yellowknives Dene First Nations peoples. We thank the Principle Investigator, Dr. Mary Hampton, and the four jurisdictional partners from Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba who worked collaborated with us on this research. We would also like to thank the project’s guiding Elder Betty McKenna. Finally, we would like to acknowledge the valuable partnership with our NWT colleagues at the YWCA of Yellowknife, RCMP G Division and the Coalition Against Family Violence. Funding for this research was provided by the Social Science and Humanities Research Council, Community/University Research Alliance (SSHRC/CURA).