Troubleshooting Miscommunication

Learning Objectives

After studying this unit, you will be able to

After studying this unit, you will be able to

-

-

- troubleshoot communication errors by breaking down the communication process into its component parts

-

Introduction

Now with a basic overview of the communication process, troubleshooting miscommunication barriers becomes a matter of locating wherein the communication process lies the problem: with the sender and the message they put together, the receiver and their feedback message, or the channel in the context of the environment between them. Identifying the culprit can help avoid costly business errors. According to Susan Washburn[1], communication problems can lead to:

- Conflict, damaged relationships, and animosity within an office and lost business with clients

- Productivity lost and resources wasted fixing problems that could have been avoided with proper communication

- Inefficiency in taking much longer to do tasks easily completed with better communication, leading to delays and missed deadlines

- Missed opportunities

- Unmet objectives due to unclear or shifting requirements or expectations

Let’s examine some of these real scenarios. Take, for instance, the misplaced comma that cost Rogers Communications $1 million in a contract dispute over New Brunswick telephone poles[2] or the absence of an Oxford comma that cost Oakhurst Dairy $5 million in a Maine labour dispute.[3] In both cases, everyone involved would have preferred to continue with business as usual rather. To avoid costly miscommunication in any business or organization, senders and receivers must be diligent in fulfilling their communication responsibilities and be wary of potential misunderstandings throughout the communication cycle.

Communication Barriers

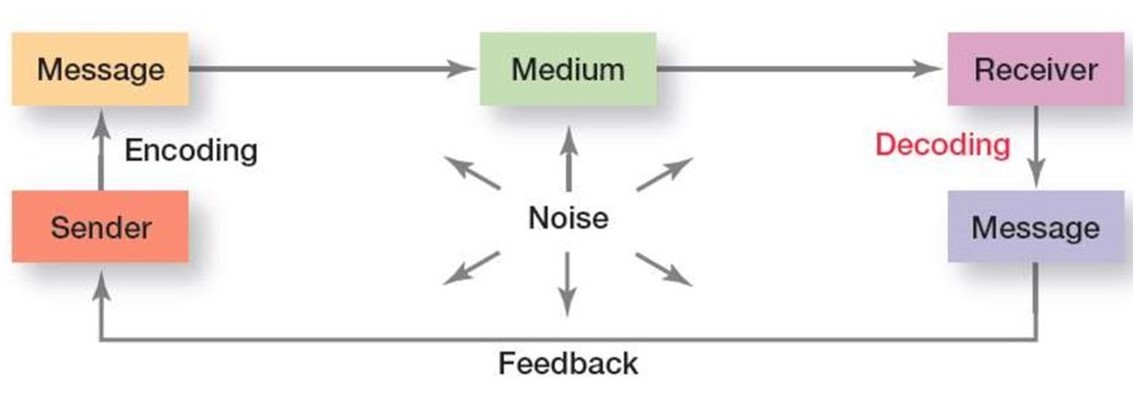

The communication process may seem simple, but it is not. There are many barriers and distractions that can inhibit clear communication between sender and receiver. How many times have you thought you communicated an idea clearly only to later understand that you were completely misunderstood? Anything that interferes with clear communication is called Noise. Clear communication can be improved by learning to recognize the noises, or barriers to clear communication, that disrupts the various steps in the communication process.

Noise in the Communication Process

Some of the most significant noises are discussed in more detail after this short video presentation of 10 Barriers to Effective Communication.

Significant Communication Barriers

Language/Bypassing: Different words have different meanings to different people. Bypassing happens when two people attached different meanings to the same word. For communication to be successful, the sender and receiver must attach the same meaning to the words, gestures, and symbols used to compose a message. Therefore, using concrete words and commonly understood symbols and gestures will decrease the chances of miscommunication.

Frame of Reference: Everyone experiences the world through a unique perspective based on individual experiences, backgrounds, culture, personality and many other factors. Thus, no two people experience the world exactly the same. To ensure communication is clear, the sender must be aware of his/her own frame of reference and the receiver’s frame of reference to achieve clear communication. For example, the frame of reference between baby-boomers and millennials is quite different. Therefore, inter-generational communication in the workplace can lead to miscommunication if the sender and receiver do not account for the different frames of reference.

Language Skills: No matter how great the message, it will not be understood or fully appreciated if the appropriate oral and written skills are not used to express the message. Spelling, grammar, sentence structure, and fluency errors all interfere with clear communication. In addition, using jargon, slang, and unfamiliar words will also decrease clear communication.

Distractions: Emotional interference, physical distractions, and digital interruptions will also decrease clear communication. Shaping an objective message is difficult when one is feeling joy, fear, resentment, hostility, sadness, or some other strong emotion. Physical distractions, such as faulty acoustics; sloppy appearance and careless formatting; as well as multi-tasking, information overload, conflicting demands can all interfere with clear communication. Focusing on what is important and shutting out interruptions increase the chances of effective communication.

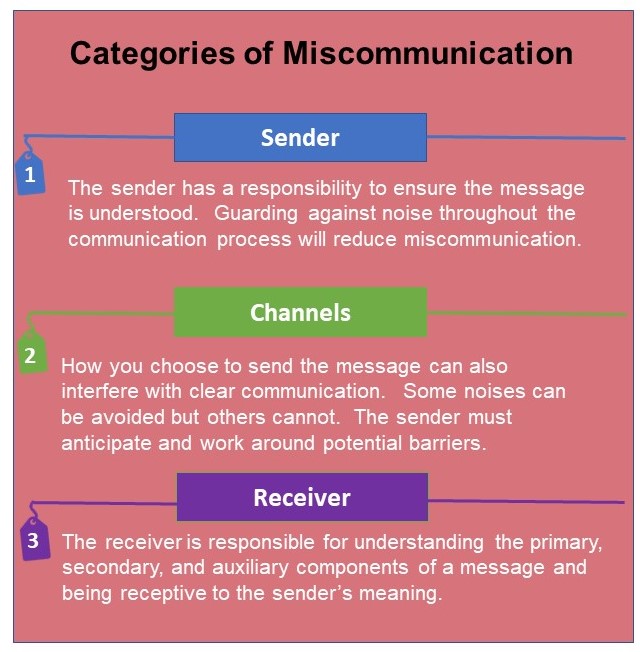

Categories of Miscommunication

Sender-related Miscommunication

The responsibility of the sender of a message is to make it as easy as possible to understand the intended meaning. If work must be done to get your point across, it is on you as the sender to do all you can to make that happen. (The receiver also has their responsibilities that we’ll examine below but listening and reading are not necessarily as labour-intensive as composing a message in either speech or writing.) This is why grammar, punctuation, and even document design in written materials, as well as excellent conversational and presentation skills, are so important: sender errors in these aspects of communication lead to readers’ and audiences’ confusion and frustration, which get in the way of their understanding the meaning you intended. If senders of messages fail to anticipate their audience’s needs and miss the target of writing or saying the right thing in the right way to get their messages across, they bear the responsibility for miscommunication and need to pay close attention to the lessons throughout this textbook to help them get back on target.

If the sender has any doubt that their message is being understood, it’s also on them to check in to make sure. If you are giving a presentation, for instance, you can employ several techniques to help ensure that your audience stays with you:

- Ensure that they can properly hear you by projecting your voice so that even the people in the back row can hear you properly; check that they can by asking if they can hear you just fine.

- Get them involved and engaged by asking for a show of hands-on topical questions.

- Ask them to ask questions if they don’t understand anything; make them feel at ease to ask questions by saying that there are no stupid questions and that if a question occurs to any one of them, it is probably also occurring to the rest.

- Flag important points and, several minutes later, ask them to summarize them back to you when you are relating them to another major point.

Channel-related Miscommunication

Errors can also be blamed on the medium of the message such as the technology and the environment—some of which can slide back to choices the sender makes, but others are out of anyone’s control. If you need to work out the terms of a sale with a supplier a few towns over before you draw up the invoice and time is of the essence, sending an email and expecting a quick response would be foolish when you (a) have no idea if anyone’s there to write back right away, and (b) would potentially need to go back and forth over the terms; this exchange could potentially take days, but you only have an hour. The smart move is instead to phone the supplier so that you can have a quick conversation. If you need to, you could also text them to say that you’re calling to hammer out the details before writing it up. Of course, you wouldn’t call using a cellphone from inside a parking garage because blame for problems with the reception (or interference) would slide back on you for not positioning yourself appropriately given the available environments. If phone lines and the internet are down due to equipment malfunction (despite paying your bills and buying trustworthy equipment), however rare that might be, the problem is obviously out of your hands and in the environment. Otherwise, it’s entirely up to you to use the right channels the correct way in the environments best suited to clear communication to get the job done.

Receiver-related Miscommunication

The responsibility of the receiver of a message is to be able to actively read or hear not only the message itself but also to understand the nuances of that message in context. Say you were a relatively recent hire at a company and were in line for a promotion for the excellent work you’ve been doing lately, it’s 11:45 a.m., you just crossed paths with your manager in the hallway, and she’s the one who said: “I’m hungry.” That statement is the primary message, which simply describes how the speaker feels. But if she says it in a manner that, with nonverbals (or secondary messages) such as eyebrows raised signaling interest in your response and a flick of the head towards the exit, suggests an invitation to join her for lunch, you would be foolish not to put all of these contextual cues together and see this as a professional opportunity worth pursuing. If you responded with “Enjoy your lunch!” your manager would probably question your social intelligence and whether you would be able to capitalize on opportunities with clients when cues lined up for business opportunities that would benefit your company. But if you replied, “I’m starving, too. May I join you for lunch? I know a great place around the corner,” you would be correctly interpreting auxiliary messages such as your manager’s intention to assess your professionalism outside of the traditional office environment.

Say you arrive at the lunch spot with your manager and sit down to eat, but it’s too noisy to hear each other well; you would be equally foolish to use this environmental problem as an excuse not to talk and instead just browse your social media accounts on your phone (perhaps your usual lunchtime routine when eating solo) in front of her. You could accommodate her need to hear you by raising your voice, but the image of you shouting at your manager also sends all the wrong messages. Rather, if you cite the competing noise as a reason to move to a quieter spot where you can converse with her in a way that displays the polish of your manners and ultimately positions you nicely for the promotion, she would understand that you have the social intelligence to control the environmental conditions in ways that prioritize effective communication.

Of course, so much more can go wrong with the receiver. In general, the receiver may lack the knowledge to understand your message; if this is because you failed to accommodate their situation—say you used formal language and big, fancy words but they don’t understand because they are EAL (English as an additional language)—then the responsibility shifts back to you because you can do something about it. You could instead use more plain, easy-to-understand language. If your audience is a co-worker who should know what you’re talking about when you use the jargon of your profession, but they don’t because they’re in the wrong position, the problem is with the receiver (and perhaps the hiring process).

Another receiver problem may have to do with attitude. If a student, for instance, believes that they don’t really need to take a class in Communications because they’ve been speaking English for 19 years, think their high school English classes were a complete joke, and figure they’ll do just fine working out how to communicate in the workplace on their own, then the problem with this receiver is that overconfidence prevents them from keeping the open mind necessary to learn and take direction. Carried into the workplace, such arrogance would prevent them from actively listening to customers and managers, and they would most likely fail until they develop necessary active listening skills (see below). Employers like employees who can solve problems on their own, but not those who are unable to take direction.

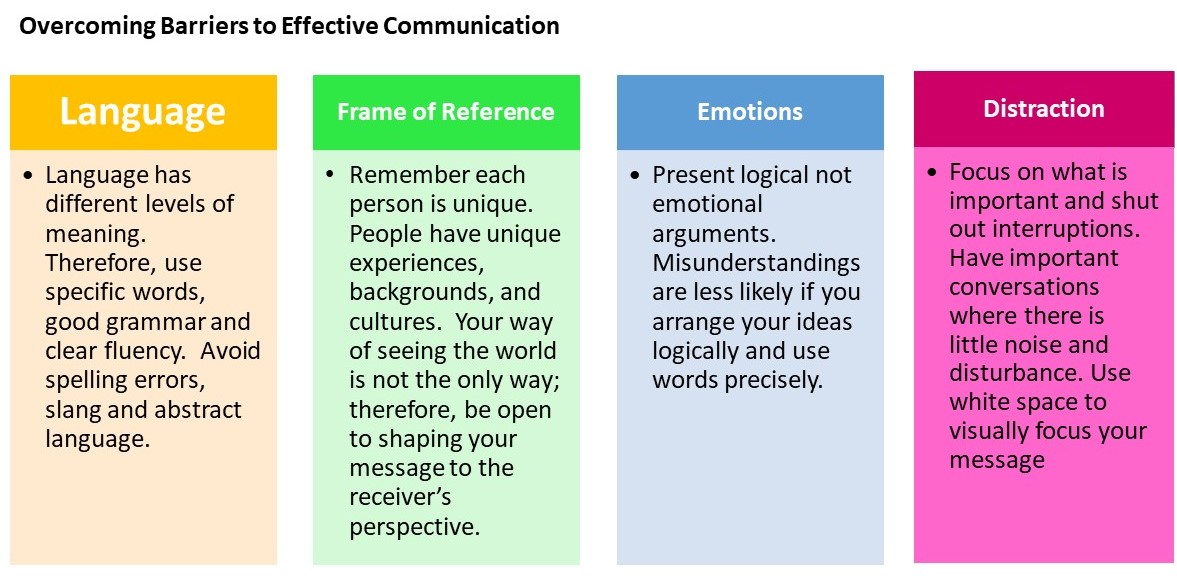

Overcoming Barriers

Understanding the nature of communication can help you overcome the many barriers that can interfere with clear communication. Recognizing that the communication process is noise-sensitive will help you anticipate the potential noises that can cause miscommunication. Figure 3.2 provides strategies to help you overcome four different categories of noise.

The picture emerging here, then, is one where many factors must work in concert to achieve communication of intended meaning. The responsibility of reaching the goal of understanding in the communication process requires the full cooperation of both the sender and receiver of a message to make the right choices and avoid all the perils—personal and situational—that lead to costly miscommunication.

Key Takeaway

Being an effective professional involves knowing how to avoid miscommunication by upholding one’s responsibilities in the communication process towards the goal of ensuring proper understanding.

Being an effective professional involves knowing how to avoid miscommunication by upholding one’s responsibilities in the communication process towards the goal of ensuring proper understanding.

Exercise

Describe a major miscommunication that you were involved in lately and its consequences. Was the problem with the sender, channel, environment, receiver, or a combination of these?

Describe a major miscommunication that you were involved in lately and its consequences. Was the problem with the sender, channel, environment, receiver, or a combination of these?

Explain what you did about it and what you would do (or advise someone else to do) to avoid the problem in the future.

Chapter Attribution

Unit 3: Troubleshooting Miscommunication in Communication@Work by Jordan Smith published by Seneca College is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- Washburn, S. (2008, February). The miscommunication gap. ESI Horizons, 9(2). Retrieved from http://www.esi-intl.com/public/Library/html/200802HorizonsArticle1.asp?UnityID=8522516.1290 ↵

- Austen, I. (2006, October 25). The comma that costs 1 million dollars (Canadian). The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2006/10/25/business/worldbusiness/25comma.html ↵

- Associated Press. (2017, March 21). Lack of comma, sense, ignites debate after $10m US court ruling. CBC News | Business. Retrieved from http://www.cbc.ca/news/business/comma-lawsuit-dairy-truckers-1.4034234 ↵

There are many different types of interviews being used in today’s job market. Understanding the most common interview formats will help you manage your expectations and prepare better.

- Structured or formal: This type of interview is very common and is used as a standardized method of comparing multiple candidates. The candidate is invited to attend a face-to-face meeting with the hiring personnel. In this format, an employer develops questions that will help assess the skills and experiences they are seeking to fulfill the requirements of the position. Many employers will have a rubric or scoring system for each question. A score is given based on the appropriateness of the candidates’ answers and then these scores are compared as a method of determining the most suitable candidate.

- Unstructured or informal: This type of interview is more casual, and may have some prepared questions, but is typically less structured. The questions may be determined or changed depending on the candidate’s responses or the direction of the conversation. In this method, the candidate has the opportunity to discuss their skills and qualifications more openly, emphasizing more of what they feel is important.

- Prescreening, video, or telephone: In an attempt to narrow the candidate pool, a telephone or video interview may be used for initial screening purposes. This interview format may also be used to interview candidates who don’t reside in the same area. When taking part in a video or telephone interview, always remember to ensure your technologies are working and are charged in advance. Remove any distractions from the background. Dress and prepare as you would for an in-person interview.

Preparation is essential in being successful in the interview process. Your research will show the interview committee your initiative, interest, motivation, and resourcefulness.

- Panel: In a panel interview, a group of interviewers, typically two to five people from various positions and roles in the company, will take turns asking questions to one candidate. By having multiple opinions involved in the hiring decision, the employer will have a broader, more objective viewpoint when making a decision on which candidate will be most suitable. During your interview, it is important to engage all of the panelists, therefore, as you answer each question, ensure that you are shifting your eye contact to address each one of them.

- Group: Often the group interview is used in order for an organization to save on time and resources by screening a larger number of candidates at the same time. The structure of a group interview may look different from employer to employer, but typically includes a series of questions to observe how candidates communicate, interact with people, and react under pressure.

- Performance, testing, or presentation: This type of interview can be arranged during a separate time or as part of a face-to-face interview. During this time, an interviewer asks the candidate to perform specified tasks related to the job within a limited timeframe. Employers cannot always make a hiring decision solely based on interview performance, therefore, depending on the job requirements, they may decide to test an individual’s ability as part of the hiring process. For example, for an administrative assistant position, you may be tested on your ability to use Microsoft Excel, for a hairdressing position you may be asked to perform a haircut, or for a teacher you may be asked to give a presentation.

CHAPTER ATTRIBUTION

Be the Boss of Your Career: A Complete Guide for Students & Grads (pressbooks.pub) by Lindsay Bortot and Employment Support Centre, Algonquin College

Learning Objectives

-

-

- identify and assess individual skills, strengths, and experiences to identify career and professional development goals

- understand effective job search strategies for today's job market

-

Introduction

If you devote a portion of your life to training for a career, nothing is more important at the end of that program than getting a job where you can apply your training. The job application process poses a challenge that requires a skillset quite different from that which your core program courses teach you, yet you cannot get a job without this skill set. In most professions, the competition for jobs is so fierce that only your communication A-game can help you through the communication test that is the hiring process.

The following video provides an overview of what you will need to do to find your dream job.

Job Search Strategies

Finding a job in this very competitive job market may require the use of traditional and non-traditional strategies. Some of these strategies are examined here.

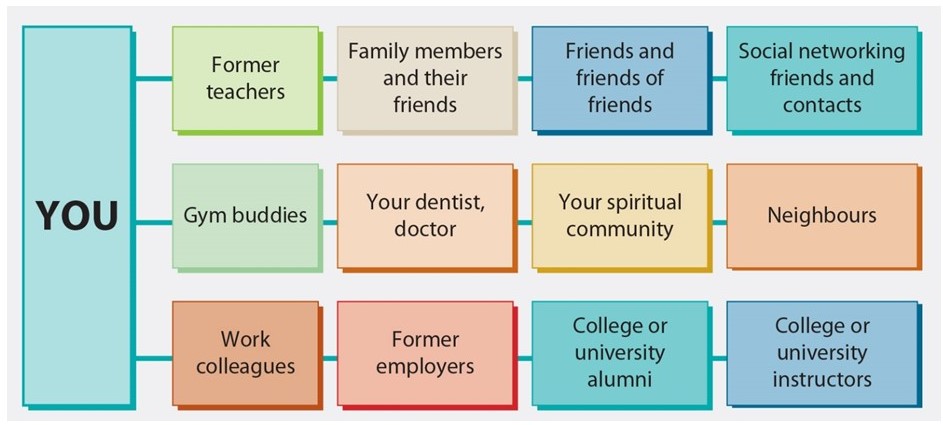

Networking

A recent study showed that approximately 61% of job seekers either used their personal network and/or online social network to land their dream job.[1] What exactly is a personal network and why is it so effective? A network is a group of people with whom you have a personal relationship based on similar interests. As you build this network and cultivate the relationships, you develop a connection and most importantly trust with your the people in your network. These relationships come in very handy because the majority of the job market is hidden, that is, jobs that are not advertised through conventional avenues. Most jobs are often found through referrals and word of mouth; thus, having a network of people that can give you inside information about available jobs in your field is invaluable. In addition to the inside information, people in your network also serve as personal references and a bridge between your potential employer and you. Some tips to help you develop a personal network include:

- Develop a list of people to speak with about your job search

- Contact the people on your list

- Call and possibly arrange a meeting with any referrals provided by your contact list

- Join an online networking group

- Conduct research on additional networking tips and trends

Online Job Sites

According to a recent Jobvite survey, job boards continue to be the number one medium to access job opportunities.[2] Major job search engines like Monster and Indeed are good places to start your job search process. However, both job seekers and employers have their objections to these sites. To job seekers, applying for a job through a job board can be frustrating for the following reasons:

- Some will strip out the formatting you’ve meticulously assembled for your résumé and cover letter

- Submitting confidential information about yourself to them feels risky

- They can feel like vast abysses into which you send dozens of applications you’ve laboured over for hours, but without ever receiving a response back

To employers and recruiters, the big job sites attract a flood of poor-quality applicants from around the world, leaving the hiring manager or committee with the time-intensive job of sorting out the applicants worth seriously considering from the droves of under-qualified applicants taking shots in the dark with what amounts to spam applications. With such a demanding selection process, employers simply don’t have time to respond to every applicant.

Nonetheless, ignoring these sites altogether would be a mistake because too many employers use them to advertise positions. When your full-time job is just to find a full-time job, you can’t leave any stone unturned. The following are sites worth searching for job postings and other information they offer on the job market: Figure 3.1.2[3]

- Job Bank

- Monster

- Indeed

- Workopolis

- CareerBuilder

- Eluta

- Jobboom

- Glassdoor

- SimplyHired

- WOWjobs

- Charity Village

Industry Conferences and Job Fairs

Attend industry conferences and network with participants. Joining a professional association and attending its meetings and conferences will give you ample opportunities to network with employers and their recruiting agents. As in the previous scenarios, this only works if you are friendly and outgoing. Conference participants who merely soak in others’ presentations and discussions without networking are effectively invisible to the recruiters. You should also attend career fairs and sign up for interviews with visiting recruiters. Because colleges are a greenhouse for the emerging labour pool, they have tight connections with industry partners . When company recruiters come to your college, be there to ask them about their employment opportunities. Recruiters aren’t interested in students who aren’t interested in them. Attending career fairs and talking to recruiters is a great way of showing interest.

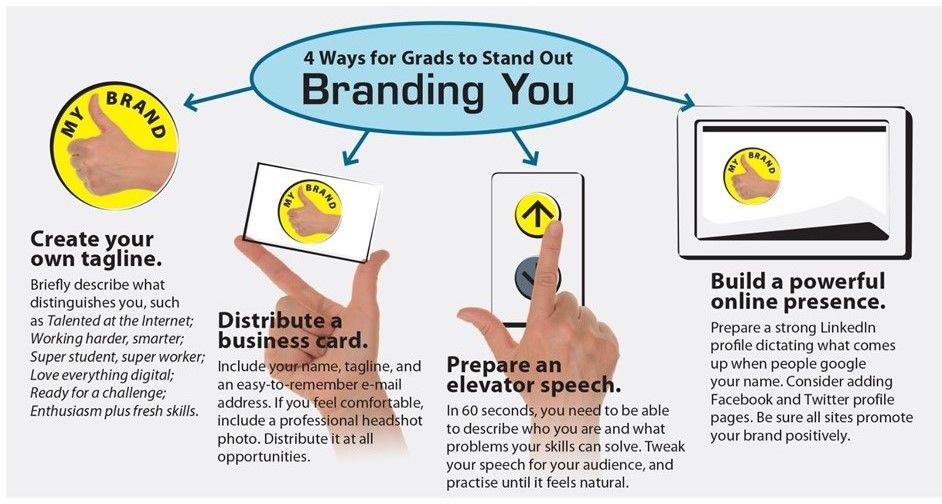

Personal Branding

What is a personal brand and how do you develop one? The following TEDx talk provides an excellent explanation of the topic.

Begin developing your personal brand by asking yourself the following questions:

- what about yourself do you want to emphasize in the job search process?

- What qualities distinguish you from everyone else?

- What unique skills can you offer your employer?

- What makes you a sought after employee?

- How will you make your future workplace better?

Use this information to promote yourself in online and offline forums. Online, create a Facebook page and a LinkedIn profile. Offline, create business cards and write a elevator pitch to introduce yourself at industry conferences and job fairs. No one will do better job at promoting you, than you will. Figure 3.1.2[4]

Exercises

- Begin developing your network. Conduct at least one referral interview or join one online networking group. Record the results you experienced and the information you learned from the networking options you chose.

- Use several of the job search engines listed in above to collect about half a dozen job postings that you would be interested in applying to if they were available upon graduation. If you can’t find any in your local region, look further afield in neighbouring cities or even other provinces or countries you’d be interested in moving to.

- Compare the various postings. Identify common terms used in the lists of required skills and job duties. What are the common work experience and educational qualifications identified as required as assets?

References

BI Norwegian Business School. (2017). The job hunting process [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WRC7y8VriuM

Guffey, M., Loewry, D., & Griffin, E. (2019). Business communication: Process and product (6th ed.). Toronto, ON: Nelson Education. Retrieved from http://www.cengage.com/cgi-wadsworth/course_products_wp.pl?fid=M20b&product_isbn_issn=9780176531393&template=NELSON

Morgan, H. (2019). A candidate's job market means stronger competition for job seekers. The savvy intern. Retrieved from https://www.youtern.com/thesavvyintern/index.php/2019/05/20/stronger-competition-job-seekers/

TEDx Talks. (2017). Designing a personal brand from zero to infinity [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Alqt7pIbp_o

CHAPTER ATTRIBUTION

Unit 47: The Job Search Process – Communication@Work (senecacollege.ca) in Communication@Work by Jordan Smith published by Seneca College is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Learning Objectives

-

-

- discuss the do and don't of employment interviewing

- understand the three phases of the interview process

- understand how to succeed in each stage of the interview process

-

Introduction

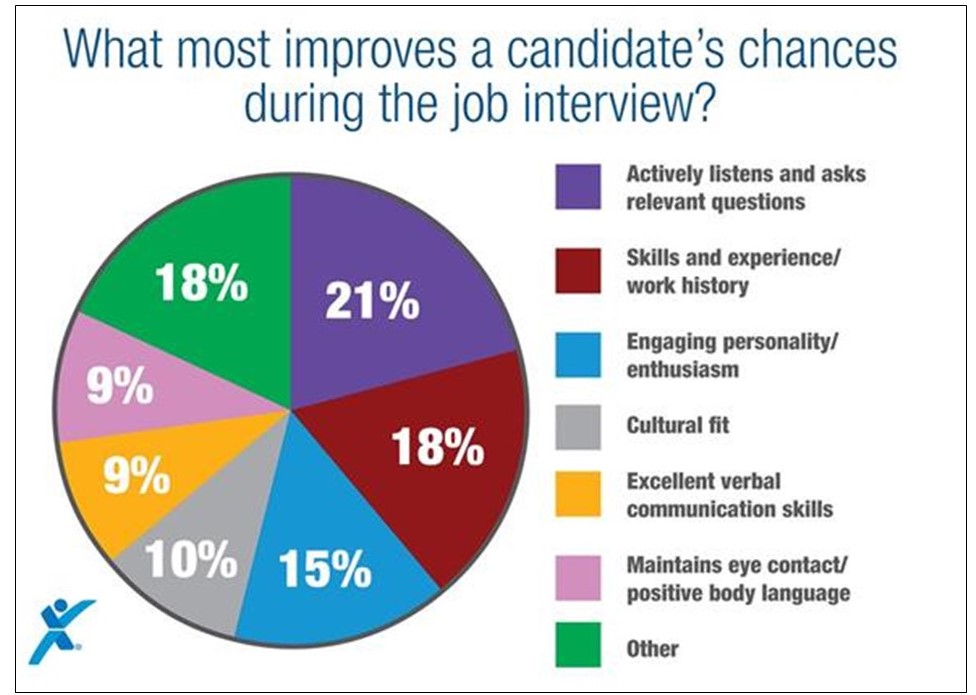

In Chapter 3, we discussed how the job application process is basically a communications test that begins with a low-difficulty written component in the cover letter and résumé, and ends with a high-level oral exam in the interview. Among other things, the interview helps the employer get to know the job applicant better and confirm that they are who their résumé and cover letter say they are. It places the burden of proving the résumé’s claims on the applicant by inviting them to speak anecdotally about them. The most successful applicants will use the interview questions as opportunities to connect their experience and qualifications to the requirements of the job at hand as stated in the job posting. The successful pitch convinces the employer that the applicant, as the solution to the problems associated with the job vacancy, is not only a good match for the role and its duties, but also a good fit for the culture of the workplace. The employer wants to confirm that the candidate will get along well with management, coworkers, and customers, which the employer can get a sense of only through conversation.

Advice about how to succeed in job interviews is about as varied as there are people offering advice on job interviews because every employer is different in how they conduct interviews and what they want to get out of them. This variety makes preparing for job interviews tricky. A job interview can be as informal as walking in to speak with a store manager without so much as a résumé. It could be as formal as a three-stage process with a pre-interview phone screening, two-hour interview in front of a panel asking the same questions of each candidate, and a follow-up hour-long interview with questions specific to the leading candidates. A rigorous interview process may have pre-interview screening procedures such as personality tests, written and oral language proficiency tests, background investigations (e.g., college transcript, criminal records check), consultations with previous employers, and even personality-assessing video games (NPR, 2013) to ensure that the employer doesn’t waste hours interviewing candidates unfit for the role. The interview may involve demonstrations of skill such as solving a complex engineering problem on a whiteboard. It may be conducted via web conference. It may be an unstructured conversation about something completely different from the work at hand and take place in a coffee shop. It may be in an off-site hotel room or in the actual workplace itself. The only consistent element in all of this variety is that you’ll have a conversation with employer or their representatives.

Let's examine this process in more detail.

The Interview Process

The invitation to interview means you have been identified as a candidate who meets the minimum qualifications and demonstrate potential as a future employee. Your cover letter, résumé, or related application materials may demonstrate the connection between your preparation and the job duties, but now comes the moment where you will need to articulate those points out loud.

If we assume that you would like to be successful in your employment interviewing, then it makes sense to use the communication skills gained to date with the knowledge of interpersonal communication to maximize your performance. There is no one right or wrong way to prepare and present at your interview, just as each audience is unique, but prepare in anticipation of several common elements.

Preparation

The right frame of mind is an essential element for success in communication, oral or written. For many, if not most, the employment interview is surrounded with mystery and a degree of fear and trepidation. Just as giving a speech may produce a certain measure of anxiety, you can expect that a job interview will make you nervous. Anticipate this normal response, and use your nervous energy to your benefit. To place your energies where they will be put to best use, the first step is preparation.

Briefly, the employment interview is a conversational exchange (even if it is in writing at first) where the participants try to learn more about each other. Both conversational partners will have goals in terms of content, and explicitly or implicitly across the conversational exchange will be relational messages. Attending to both points will strengthen your performance.

On the content side, if you have been invited for an interview, you can rest assured that you have met the basic qualifications the employer is looking for. Hopefully, this initiation signal means that the company or organization you have thoroughly researched is one you would consider as a potential employer. Perhaps you have involved colleagues and current employees of the organization in your research process and learned about several of the organization’s attractive qualities as well as some of the challenges experienced by the people working there.

Businesses hire people to solve problems, so you will want to focus on how your talents, expertise, and experience can contribute to the organization’s need to solve those problems. The more detailed your analysis of their current challenges, the better. You need to be prepared for standard questions about your education and background, but also see the opening in the conversation to discuss the job duties, the challenges inherent in the job, and the ways in which you believe you can meet these challenges. Take the opportunity to demonstrate the fact that you have “done your homework” in researching the company. Table 3.1 “Interview Preparation Checklist” presents a checklist of what you should try to know before you consider yourself prepared for an interview.

Table 3.1 Interview Preparation Checklist

| What to Know | Examples |

|---|---|

| Type of Interview | Will it be a behavioral interview, where the employer watches what you do in a given situation? Will you be asked technical questions or given a work sample? Or will you be interviewed over lunch or coffee, where your table manners and social skills will be assessed? |

| Type of Dress | Office attire varies by industry, so stop by the workplace and observe what workers are wearing if you can. If this isn’t possible, call and ask the human resources office what to wear—they will appreciate your wish to be prepared. |

| Company or Organization | Do a thorough exploration of the company’s Web site. If it doesn’t have one, look for business listings in the community online and in the phone directory. Contact the local chamber of commerce. At your library, you may have access to subscription sites such as Hoover’s Online[5] |

| Job | Carefully read the ad you answered that got you the interview, and memorize what it says about the job and the qualifications the employer is seeking. Use the Internet to find sample job descriptions for your target job title. Make a written list of the job tasks and annotate the list with your skills, knowledge, and other attributes that will enable you to perform the job tasks with excellence. |

| Employer’s Needs | Check for any items in the news in the past couple of years involving the company name. If it is a small company, the local town newspaper will be your best source. In addition, look for any advertisements the company has placed, as these can give a good indication of the company’s goals. |

Performance

To prepare for an employment interview, research the company, market, and even individuals in your effort to learn more about the opportunity. From this solid base of preparation, you need to begin to prepare your responses. Would you like some of the test questions before the test? Luckily for you, employment interviews involve a degree of uniformity across their many representations. Here are 10 common questions you are likely to be asked in an employment interview

- Tell me about yourself.

- Have you ever done this type of work before?

- Why should we hire you?

- What are your greatest strengths? Weaknesses?

- Give me an example of a time when you worked under pressure.

- Tell me about a time you encountered (X) type of problem at work. How did you solve the problem?

- Why did you leave your last job?

- How has your education and/or experience prepared you for this job?

- Why do you want to work here?

- What are your long-range goals? Where do you see yourself three years from now?

When you are asked a question in the interview, look for its purpose as well as its literal meaning. “Tell me about yourself” may sound like an invitation for you to share your text message win in last year’s competition, but it is not. The employer is looking for someone who can address their needs. Telling the interviewer about yourself is an opportunity for you make a positive professional impression. Consider what experience you can highlight that aligns well with the job duties and match your response to their needs.

In the same way, responses about your strengths are not an opening to brag, and your weakness not an invitation to confess. If your weakness is a tendency towards perfectionism, and the job you are applying for involves a detail orientation, you can highlight how your weaknesses may serve you well in the position.

Consider using the “because” response whenever you can. A “because” response involves the restatement of the question followed by a statement of how and where you gained education or experience in that area. For example, if you are asked about handling difficult customers, you could answer that you have significant experience in that area because you’ve served as a customer service representative with X company for X years. You may be able to articulate how you were able to turn an encounter with a frustrated customer into a long-term relationship that benefited both the customer and the organization. Your specific example, and use of a “because” response, can increase the likelihood that the interviewer or audience will recall the specific information you provide.

You may be invited to participate in a conference call, and be told to expect the call will last around twenty minutes. The telephone carries your voice and your words, but doesn’t carry any visual cues. If you remember to speak directly into the telephone, look up and smile, your voice will come through clearly, and you will sound competent and pleasant. Whatever you do, don’t take the call on a cell phone with an iffy connection—your interviewers are guaranteed to be unfavorably impressed if you keep breaking up during the call. Use the phone to your advantage by preparing responses on note cards or on your computer screen before the call. When the interviewers ask you questions, keep track of the time, limiting each response to about a minute. If you know that a twenty-minute call is scheduled for a certain time, you can anticipate that your phone may ring may be a minute or two late, as interviews are often scheduled in a series while the committee is all together at one time. Even if you only have one interview, your interviewers will have a schedule, and your sensitivity to it can help improve your performance.

You can also anticipate that the last few minutes will be set aside for you to ask your questions. This is your opportunity to learn more about the problems or challenges that the position will be addressing, allowing you a final opportunity to reinforce a positive message with the audience. Keep your questions simple, your attitude positive, and communicate your interest.

At the same time as you are being interviewed, know that you too are interviewing the prospective employer. If you have done your homework you may already know what the organization is all about, but you may still be unsure whether it is the right fit for you. Listen and learn from what is said as well as what is not said, and you will add to your knowledge base for wise decision making in the future.

Above all, be honest, positive, and brief. You may have heard that the world is small and it is true. As you develop professionally, you will come to see how fields, organizations, and companies are interconnected in ways that you cannot anticipate. Your name and reputation are yours to protect and promote.

Post-performance

You completed your research of the organization, interviewed a couple of employees, learned more about the position, were on time for the interview (virtual or in person), wore neat and professional clothes, and demonstrated professionalism in your brief, informative responses. Congratulations are in order, but so is more work on your part.

Remember that feedback is part of the communication process: follow up promptly with a thank-you note or e-mail, expressing your appreciation for the interviewer’s time and interest. You may also indicate that you will call or e-mail next week to see if they have any further questions for you. (Naturally, if you say you will do this, make sure you follow through!) In the event that you have decided the position is not right for you, the employer will appreciate your notifying them without delay. Do this tactfully, keeping in mind that communication occurs between individuals and organizations in ways you cannot predict.

After you have communicated with your interviewer or committee, move on. Candidates sometimes become quite fixated on one position or job and fail to keep their options open. The best person does not always get the job, and the prepared business communicator knows that networking and research is a never-ending, ongoing process. Look over the horizon at the next challenge and begin your research process again. It may be hard work, but getting a job is your job. Budget time and plan on the effort it will take to make the next contact, get the next interview, and continue to explore alternate paths to your goal.

You may receive a letter, note, or voice mail explaining that another candidate’s combination of experience and education better matched the job description. If this happens, it is only natural for you to feel disappointed. It is also only natural to want to know why you were not chosen, but be aware that for legal reasons most rejection notifications do not go into detail about why one candidate was hired and another was not. Contacting the company with a request for an explanation can be counterproductive, as it may be interpreted as a “sore loser” response. If there is any possibility that they will keep your name on file for future opportunities, you want to preserve your positive relationship.

MORE EXamples and details

The remaining sections of this chapter will provide more specific details and examples to help you improve your interview skills.

Exercises

- Find a job announcement of a position that might interest you after you graduate or reach your professional goal. Write a brief statement of what experience and education you currently have that applies to the position and note what you currently lack

- What are the common tasks and duties of a job you find interesting? Create a survey, identify people who hold a similar position, and interview them (via e-mail or in person).

- What has been your employment interview experience to date? Write a brief statement and provide examples.

References

Anonymous. Communication For Business Success. Retrieved from http://2012books.lardbucket.org/books/communication-for-business-success/. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

Doyle, A. (2020). How to prepare for a job interview. The Balance. Retrieved from https://www.thebalancecareers.com/how-to-prepare-for-a-job-interview-2061361

GlobalNewswire. (2018). What's the key to a successful job interview? Retrieved from https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2018/04/11/1468553/0/en/What-s-the-Key-to-a-Successful-Job-Interview.html

Guffey, M., Loewry, D., & Griffin, E. (2019). Business communication: Process and product (6th ed.). Toronto, ON: Nelson Education. Retrieved from http://www.cengage.com/cgi-wadsworth/course_products_wp.pl?fid=M20b&product_isbn_issn=9780176531393&template=NELSON

Indeed. (2020). Top interview tips: Common questions, body language & more [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HG68Ymazo18

McLean, S. (2005). The basics of interpersonal communication. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

CHAPTER ATTRIBUTION

Unit 49: Interview Skills – Communication@Work (senecacollege.ca) in Communication@Work by Jordan Smith published by Seneca College is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.