7 Creating an inclusive school for refugees and students with English as a second language or dialect

Susan Carter

How can school communities create an inclusive school?

Key Learnings

- The Australian demographic is now a fast changing increasingly diverse population.

- Every individual is shaped and influenced by individual experiences, many of which remain unrevealed to others so the challenge is both in recognising diversity and accepting the diversity that we cannot see nor yet understand.

- Inclusion involves accepting difference and catering for the individual needs of learners.

- At the heart of any inclusive school is the creation of a culture where each individual is accepted and embraced for who and what they bring to the learning space.

INTRODUCTION

It could be argued that inclusion into society is a basic need for humans. Schools in Australia and internationally, are exploring what this really means in a fast changing global context. Challenges face our educators as never before as the rate of migration has vastly increased with more people seeking asylum than at any time since World War II (Gurria, 2016). Schools face challenges in educating students who have little understanding of the official language or the school’s cultural context. This chapter seeks to bring into focus inclusion for students new to Australia, with limited or no English speaking skills. It specifically explores the inclusive practices of one Australian school and seeks to share the effectual ways that they support, engage, enculturate and educate students. Through case study methodology, the data findings revealed in this chapter highlight a way of working that facilitates the creation of a shared culture, a place where individuals share that they feel safe and included. The cost of caring is however a pragmatic consideration that educators face and this chapter outlines some strategies on how to engage community help and create a sense of hopefulness.

Our schools are changing. Schools in Australia and indeed internationally are opening their community to refugees and migrants at a rate that has not been experienced before. Refugees are seeking safe places at rates higher than at any time since World War II (Gurria, 2016). In 2015, approximately 244 million people were living in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development {OECD} countries outside their country of birth (Gurria, 2016). Currently, the OECD is an assembly of 34 industrialised countries that design and advocate for economic and social policies. The 34 OECD member countries are: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Chile, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Korea, Luxembourg, Mexico, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, the United Kingdom, and the United States (Hylén, Damme, Mulder, & D’Antoni, 2012). Many of the families residing in these countries arrive at state/publicly funded schools that are expected to provide equity of access and learning opportunities for all students. In reality this is an extremely complex process of catering for differing values, beliefs, ideas, and opinions on what this looks like and how it is enacted. School communities need to be encouraged to embrace a shared philosophy of inclusion and participate in practices that encourage equity, viewing changes in student population and diversity as an opportunity for learning (Carter & Abawi, 2018).

This chapter is based around the way of working that one Australian school with 52% of its student population with English as a second language or dialect {ESLD} has embraced to create an inclusive school community where there is an explicit focus on the positive learning achievements of every student. The school known as Darling Heights State School, is located in a large regional city near a university where researchers are welcomed in to help contribute to growing a learning culture. The school has been able to create an inclusive school culture and the school community wishes to share their learnings with others.

There are four specific sections to this chapter. Section one will begin by exploring the theoretical underpinning of inclusion. Section two is a scenario section that focuses on knowledge synthesis and application. Three specific animated characters in various scenarios are introduced and readers are expected to describe how they would create an inclusive environment for the character. Section three focuses on meaning making. Knowledge acquisition is challenged and deepened as readers can then explore the actual scenarios that the animated characters were based upon to see how the school created an inclusive environment for the real person. The last section encourages the reader to analytically reflect upon their knowledge and understandings of inclusion and consider how this can be applied into their real world context. The need to ensure our teachers have knowledge, skills and attitudes to create inclusive learning opportunities for students is clear but the how this is done is somewhat more complex. It is hoped that your engagement with this chapter will foster the development of new knowledge and understandings that prove useful in enacting inclusive practices.

Theoretical exploration

Inclusion is perceived differently within the literature and Maclean suggests that it is an “increasingly contentious term that challenges educators and education systems” (2017, p. 528). Within Australia the focus has been both at the whole-school and in-class support level (Forlin, Chambers, Loreman, Deppeler, & Sharma, 2013) with discussion centred on inclusion being about what is in the best interests of individual students based on the key features of participation, and integration together with the removal of elements that marginalise or exclude (Queensland Department of Education, 2018). Other researchers go further and suggest that inclusion must be a way of thinking, a philosophy held by educators that encompasses the recognition and removal of barriers to learning and values all members of a school community (McLeskey, Rosenberg, & Westling 2013). This chapter is based around the McLeskey, Rosenberg, and Westling (2013) definition where the school involved does not just try and educate the child but goes further to help the family engage in the community and access supports that enable the enrolled student/s to engage fully in all parts of school life. Carter and Abawi (2018, p. 2) aver that “inclusion is defined as successfully meeting student learning needs regardless of culture, language, cognition, gender, gifts and talents, ability, or background.” They go on to say that the needs, often considered as special needs should be appropriately supported. Within the literature ‘special needs’ have been linked to disadvantage and disability, but Carter and Abawi (2018) define special needs more broadly as “the individual requirements of a person, and the provision for these specific differences can be considered as catering for special needs” (p. 2).

Refugees and migrants are identified in this paper as having English as a Second Language or Dialect {ESLD} or what some literature terms as English as a Foreign Language {EFL} learners (Roberts, 2016). Migrants and Refugees are however very different groups. It is acknowledged that some refugee children may have increased exposure to experiences of violence, persecution, rape, torture, and abrupt dislocation (Lusk, McCallister, & Villalobos, 2013) while some migrants may have had more opportunity to move with differing levels of financial security (Black, Adger, Arnell, Dercon, Geddes, & Thomas, 2011). This paper does not explore the specifics of the groups but rather it explores the individual needs of students and families and their inclusion in a specific school. Inclusive schools move beyond what Mathews (2008) termed as piecemeal interventions to creating welcoming learning environments and spaces for participation, providing communication supports, developing positive relationships, encouraging friendships, developing a sense of belonging, and fostering learning about oneself and others. Schools that have a whole school focus on inclusion reduce the vulnerability and build resilience for refugee students (West 2004) and provide hope for the future (Rutter, 2006).

Scenario exploration

Kirk, Gallagher, Coleman, and Anastasiow (2012, p. xxix) assert that “one of the major challenges that teachers face in schools today is meeting the wide range of student needs”. They point out that the majority of classes will most likely have students that have been diagnosed with disabilities and other students who require more scaffolded support in order to achieve success. Some students will have behaviour problems, social emotional adjustments difficulties and /or emotional difficulties. Such a wide range of student needs can feel overwhelming to a teacher (Kirk, Gallagher, Coleman, and Anastasiow, 2012, p. xxix) amid all of the complexities in a school and the challenges of knowing and catering for the individual needs of all children. Given the information that you have read on inclusion I hope you feel ready to engage in exploring your understanding of inclusion through some animated scenarios. Below are three scenarios that allow exploration of inclusion from differing perspectives.

Understanding diversity: A snapshot

Statistics from the 2016 Australian National Census, depict that 33.3 % of Australians were born overseas, and a further 34.4% of people had both parents born overseas. Analysis highlighted that in 2016 nearly half (49%) of all Australians were either born overseas or had at least one parent who was born overseas. This State School’s statistics for being born in an overseas country, are even higher with 52% of students born overseas. Given this information consider how diverse that makes the Australian population and the inherent complexity in not only recognising diversity but catering for it in schools and embracing it as a part of our national culture.

Darling Heights State School has a current enrolment of 690 students and the ten most commonly reported countries of birth for students born overseas are depicted in the table below:

| Country | Number of students | % of students |

| Iraq | 61 | 8.8 % |

| Kenya | 15 | 2.1% |

| Congo, Democratic Republic | 12 | 1.7% |

| Libya | 12 | 1.7% |

| Sudan | 9 | 1.3% |

| Afghanistan | 8 | 1.1% |

| Uganda | 8 | 1.1% |

| India | 7 | 1% |

| Malawi | 7 | 1% |

| Zambia | 7 | 1% |

Watch and respond: Activity one

- Please engage in thinking about what it means to be inclusive by engaging with the animations and the videos. Instructions for activity one which consists of three separate scenarios – please carefully read:

- Do NOT refresh – If you refresh your responses are deleted.

- You must complete a response to each question in order to move to the next section. All responses to the three scenarios need to be completed and then you can save as a PDF or print. If you quit out mid way through your responses are lost.

- I strongly recommend you copy your responses and save into a word document as you go so that you can edit these later. It also means that you can stop and return to the activity later and still have your previous answers.

- This activity takes approximately an hour and a half, allowing 45 minutes to view the three animations and videos, and 45 minutes to respond to the questions. You can chose to break it into shorter segments and return to it but you must save your responses into a separate word document.

Engage here with activity one (it will open in a new tab).

MEANING MAKING

At the heart of any inclusive school is a culture of individual acceptance where diversity is respected, perhaps even considered the norm and individuals are valued for what they bring to the learning journey. Inclusion is based upon social justice where individuals are perceived as having rights to a quality education. Such an understanding of inclusion raises questions:

- What does respect for diversity mean?

- How is inclusion enacted?

- What are the possible challenges and rewards of creating an inclusive learning environment?

Darling Heights State School has embraced inclusion at a whole school level where the needs of individual students are a focus, the student’s well-being is fore-fronted, and a school team of experts support the individual needs of students and families. The school has several classrooms where intensive English lessons are run and these classrooms are known as the Intensive English Centre {IEC} and the teachers and teacher aides that work at the IEC are expert in their knowledge of supporting and engaging families with EALD and providing quality learning outcomes for students and outreach supports to classroom teachers.

In the Scenario 1- The Student video, did you notice:

- The depth of understanding participants had about this child and the expansive opportunities in place to support this child?

- The engagement all participants had in the discussion and willingness to share experiences and ideas to support the teaching and learning of this child?

- The shared understanding all participants had in ensuring the parents were involved in the learning program for this child?

- The excitement shown when the smallest of improvements or achievements were registered?

- What factors were taken into account in accepting diversity and engaging a student through inclusive practices?

In Scenario 2 – The Teacher, did you notice:

- How critical it was that all school staff acknowledge the importance of working in teams to support children?

- That ensuring the vision for the school is critical in establishing and maintaining culture?

- References that were made to particular principles for the School’s Pedagogical Framework?

- Which of the 5 principles: Community, Relationship, Diversity, Learning, Achievement, were evident for you?

- Would you have felt supported in this new or unknown setting?

- What factors were taken into account in supporting this teacher and how this teacher is included in the school community:

This video for Scenario 2 – The Teacher, outlined several programs that the school had in place to support students. The programs focuses on the primary goals:

- to support parents to engage with the school as a learning community

- to support and guide parents to establish positive learning environments at home that support their children’s learning needs; and

- to foster in parents a deeper understanding of the school and the Australian educational system while promoting active engagement in school processes and increased student academic success.

After engaging with Scenario 3 – The Parent did you notice:

- What efforts the school had made to support the parent?

- What this parent values and appreciates within the school and community?

- The depth of support that can be provided by a Parent Engagement Officer?

- What factors were taken into account in supporting this family and how is the family included in the school community?

In our schools, consider the diversity of our families, and the diversity of experiences between refugees and migrants, no one person’s journey is the same. Research depicts that migrant children are faced with hostility and segregation at school (Devine, 2009); challenges with identity and a sense of belonging (NiLaoire, Carpena-Mendez, Tyrell, White, 2011) and coping with changed family structures post migration (White, 2011). Sime and Fox (2015) suggest that moving to a new country is marked by anxiety, excitement and practical challenges. Such challenges can involve:

- Philosophy: attitudes, values, beliefs and perspectives; religion; life experiences

- Socioeconomic background and access to services such as health

- Variable skills and capabilities and value placed upon education

- Ethnicity – language, religion and cultural diversity

- Demographics: socio-economic, citizenship, location.

- Interests: music, sport etc.

Key Principles and ways of working of this inclusive school

This school community evidences six principles that recent research has highlighted as underpinning the creation of an inclusive culture (Abawi, Carter, Andrews & Conway, 2018):

- Principle 1 Informed shared social justice leadership at multiple levels – learning from and with others

- Principle 2 Moral commitment to a vision of inclusion – explicit expectations regarding inclusion embedded in school wide practice

- Principle 3 Collective commitment to whatever it takes – ensuring that the vision of inclusion is not compromised

- Principle 4 Getting it right from the start – wrapping students, families and staff with the support needed to succeed

- Principle 5 Professional targeted student-centred learning – professional learning for teachers and support staff informed by data identified need

- Principle 6 Open information and respectful communication – leaders, staff, students, community effectively working together

These six principles are intertwined in the schools way of working. In establishing an inclusive school culture the principal has spent time in visioning what the school community could look like, working with the community to capture the context and the people in a way that has grown a lived shared vision of inclusive practice where all students are expected to achieve. The purpose of this action was to create a collective commitment to a philosophy of ‘whatever it takes’ to ensure that the school put in place all possible resources and strategies to cater for the needs of students, expecting and catering for diversity in an inclusive way. When visiting the school and observing practices it was evidenced that the Principal clearly articulates, displays and models the school vision of inclusivity. In an interview he outlined the key characteristics as:

- Setting a clear direction where values and beliefs are aligned with practices

- Embedding a culture of care where diversity is accepted, expected, and appreciated

- Ensuring quality curriculum and pedagogy

- Promoting professional learning

- Ensuring safe and orderly environments

- Supporting the strengths of teachers (Principal, 2017)

Figure 7.1 highlights one example of how the clear direction of the school is made explicit in the School Wide

Pedagogical Framework. The visual representation that staff see on a daily basis where values and beliefs are fore fronted and expected to align with practices. These core principles are promoted within the school community (as displayed on the table) and these principles are embedded in the School Wide Pedagogical Framework {SWPF}, which seeks to capture how those within the school operate. By having the SWPF on the table, it means it is within view, deliberately fore fronted in the eyes of everyone who works, meets or eats at the table.

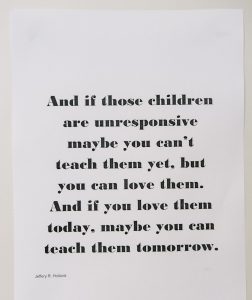

Within the same room, and throughout the school the visual representation of care is captured as shown Figure 7.2. The culture of care was verbally evidenced in classrooms, on parade, and it could be seen in the way that staff, students and parents interacted with each other.

The school focuses on creating a caring and inclusive culture and uses visual representation in a colourful way to illustrate their vision, values and beliefs as shown below in the Mural of a Harmony Tree, in Figure 7.3.

The mural captures the living, breathing and growing of a school community and the visual representation of the tree in harmony with its surroundings, aligns with the tree depicted in the SWPF. This image of the Jacaranda tree is a derivative of the schools Motto “Grow with Knowledge, Many Paths Many Futures”.

The table graphic, the posters and the mural are visual representations of the core values of the school that underpin the way the school works. These visual representations act as a key daily reminder that the school is focused on diversity and inclusion to staff who work in the meeting room, to students, and to the school community who see the mural on the main wall in the school, that the school is focused on diversity and inclusion.

The principal invested time and knowledge in building professional learning networks with the neighbouring university, inviting researchers in to work with the school on a variety of projects. The purpose of this action was the establishment of shared social justice leadership at multiple levels where staff, parents, students and the broader community were engaged in learning from and with others so they felt included and empowered to learn. The focus was and continues to be on connecting credible theory to practice. This occurs in many ways such as providing mentors for new or beginning teachers, on-going expert professional development, informed data collection, analysis together with deep pedagogical discussion, on-going feedback cycles, and specifically engaging teachers and staff members to buy-in to the development of collaborative relationships that further enhance teachers’ knowledge and understanding of inclusive practice and ways to enhance the learning environment for all students.

A synthesis of research on parental involvement in education compiled by Henderson and Mapp (2002), depicts the importance of parental involvement, an element of schooling clearly acknowledged by the school where they have invested in the employment of a family liaison officer. The purpose in creating this role involved ‘getting it right from the start’, wrapping students, families and staff with the support needed to succeed. “When families of all backgrounds are engaged in their children’s learning, their children tend to do better in school, stay in school longer, and pursue higher education” (Henderson & Mapp, 2002, p. 73). The role of the school appointed family liaison officer is featured as pivotal. Matthews (2008) suggests that the role of a school liaison worker is a key in brokering intercultural knowledge and enculturating both the school and families into a way of proactively appreciating difference that should be embedded in school culture. Hek (2005) suggests that they develop a sophisticated repertoire of understandings about everyday issues and questions, and that this knowledge serves to mitigate social exclusion and help develop cultural understandings and build self-worth through whole-school interventions.

For families being included into the school community, the focus was on providing the initial support to mitigate barriers, upskilling people and scaffolding their learning together with the expectation that they needed to learn so that they could meaningfully engage in community life. The school did not enable a deficit model of learned helplessness but deliberately scaffolded for positive learning experiences with a strong moral commitment to a vision of inclusion. A community of care was also inbuilt into this learning relationship where people (such as the school community liaison officer, and the deputy principal) routinely checked to ensure that families were doing well and supports were either added or withdrawn based upon need. Families were helped to see themselves as learners, developing English speaking skills and having opportunities for employment.

The school has over time, developed an understanding of ethnic and cultural differences, sought to determine reasons for forced migration and refugee fleeing conflict so that they were better placed to appreciate the diversity and the complexities of creating an inclusive environment. Engaging teacher aides who are fluent in students’ home language and in English has also been a focus. This enables discussions and questions in both languages and responses that are culturally sensitive and appropriate (Janinski, 2012) and the sharing of this knowledge helps to build the school community’s cultural sensitivity. Matthews (2008) highlights the importance of developing an understanding of people’s differing situations and the importance of identifying specific individual issues and needs, averring that schools are in a position to advocate for the rights of all individuals to non-discriminatory education. The suggestion is for an education that can influence the world towards inclusive peaceful possibilities where everyone is seen as having potential. While this may seem a lofty ideal, Adlous Huxley suggested that “there is only one corner of the universe you can be sure of improving and that is your own self” (Guide, A. S. A. R., 2013, p. 17). This quote has been embraced by the Principal where he has actively sought to champion social justice and has influenced his staff and students to do the same, and in so doing improve a corner of the universe.

The school also had spent a decade supporting teachers to upskill in how best to teach students with ESLD and engage their families. An important aspect of this has been acquiring an understanding of identity formation. Miller, Mitchell, and Brown (2005) suggest the importance of developing a deep understanding of how background factors can disrupt identity formation as students seek ways to balance conflicting demands and to reconcile their present and past lives.

Schools focusing on inclusion can be stabilising elements in the uncertain lives of refugee students (Matthews, 2008) and migrant students, providing safe places for new learning and interactions (Alexander, 2017). Alexander (2017) suggests that migrant children are often disadvantaged post migration and develop their own mechanisms to mitigate the impact of migration because they already have a developed set of skills, such as resilience. Orellana, (2009) suggests they are looking to a better future where educational opportunity is valued. Education is often perceived by migrant families as a way to facilitate intellectual and personal development; grow income, obtain an occupation and engage in the community (Alexander, 2017).

Being inclusive at Darling Heights State School involves thinking deeply and broadly about what the educational experience might be from someone else’s perspective and actively obtaining information from diverse sources to build an accurate picture of the student and their needs, including family needs that might impact the student’s educational outcomes. It involves understanding diversity. The school offers what Rutter (2006) suggested should be a requirement: a whole school focus on ensuring literate futures, informed by knowledge and understandings of post and pre displacement concerns. From a whole school perspective the team involved in taking the enrolment (initially office staff and then Principal, or a Deputy Principal) develop an understanding of the context and put in place supports to ensure that the initial interview meeting has positive outcomes.

In practice the policy of inclusion involves removing communication barriers. Initially this involves organising another person who speaks the same language to attend the initial enrolment interview so that communication can be effectual, and the immediate needs of the students and family can be ascertained. The school promotes engaging in open information where supports, processes, ways of working are clearly espoused, enacted and consistently modelled. There is also a clear expectation of the utilisation of respectful communication that enables the community to effectively work together. The focus is on developing a positive and supportive relationship based on establishing, up front, the clear perception that the school is here to work with families and families are expected to work together with the school. The parent and student engagement officer is involved in ensuring community linkage for necessary family supports and providing on-going connection and supports when needed. The focus is on helping families to be enculturated in the community but also to learn to how to support themselves. Parents are valued as having an important role in the education of the student and their viewpoint is both invited and listened to so that the parents’ perception of the individual skills and needs of their child, is heard.

Within the classroom context the teacher is recognised as a key link to enabling positive and engaged learning. As such the school ensures that supports are put in place to help the teacher be the best teacher they can be, enabling the learning journey for both teacher and student. Research suggests that teachers are key to producing literacy outcomes needed for educational success, post school options, life choices, and social participation (Mathews, 2008). Language Policy and Planning {LPP} research highlights the connection between official and local policy interpretation and appropriation for students with EALD (Alexander, 2017). Meken and Garcia (2010) aver that classroom teachers are key agents in supporting EALD students and in implementing policy. The school featured in this chapter did not expect teachers to cope, they challenged and supported teachers to competently engage, support and provide a quality educational experience for all learners.

There was consistent evidence of an inclusive environment that was resourced, mindful, supportive, colourful, inviting, safe, stimulating and purposeful, as highlighted in Figure 7.4.

Characteristics of inclusive classrooms

Shared attitudes and expectations are evidenced across the school in relation to diversity and inclusion. Attitudes, and expectations were evidenced that focused on acknowledging diversity and accepting the professional responsibility of understanding, planning and catering for diversity. There was also a shared commitment to inclusive practices with an explicit focus on providing a quality education for all students. The professional development of teachers and teacher aides regularly linked to legislative reminders as well as moral and ethical obligations that fore fronted the valuing of inclusion as more than an obligation. The school community focused on ensuring professional targeted student-centred learning where professional learning for teachers and support staff was informed by data where identified needs were explicitly addressed. Inclusion was and still is portrayed as the way of accepted working in the school. Staff were explicitly aware that “all school sectors must provide all students with access to high-quality schooling that is free from discrimination based on gender, language, sexual orientation, pregnancy, culture, ethnicity, religion, health or disability, socioeconomic background or geographic location” (MCEETYA, 2008, p.7).

Teachers with expert knowledge coached and mentored other teachers supporting them within the classroom, facilitating their opportunities to increase their knowledge, understanding, and implementation of inclusive practices. This involved coordinated and administratively supported planning times; collaborative group, team and school processes; and in-class strategies and resource supports. Such support necessitates significant adjustments to school organisation and pedagogical practice that meets the needs of a highly diverse population of students with a broad range of skills, knowledge, and understandings (McLeskey & Waldron, 2002; Smith & Tyler, 2011).

At a classroom level the instructional practices and accommodations used by teachers for ESLD learners were modelled and teachers were supported by experienced and knowledgeable educators in best practice. Instructional practices were centred on what worked best with an individual student and how best to teach to fill the gap in their learning ensuring that they could demonstrate this learning. For some students this involved intensive on-arrival English-language programs delivered in a specific classroom, with English lessons also provided out of work hours for parents. The instructional practices often targeted a group of students who appeared to have similar learning needs with individual students taught in differing ways and with different resources. The intervention was clearly targeted, based on the specific needs of individual learners. Educators acknowledged that refugee students with interrupted schooling face the daunting task of acquiring English and may also have other additional learning needs. For this reason, a team of educators were used to support and monitor the progress of individual students so that positive education outcomes were set based on individual targets. If individual targets were not achieved, then exploratory questions were asked, such as ‘why has this occurred’ and ‘what needs to be done differently to support this learner’?

The decisions made regarding the provision of accommodations for students with special needs were complex, informed by data, collaborative, and involved three levels of decision making. Firstly, the decisions were made from a whole school perspective in alignment with the school vision and policy (principal led process); secondly they were collaboratively refined by teaching staff who engaged in on-going professional dialogue where the needs of the individual child were fore-fronted and then the clustering of student needs were aligned with resources; and thirdly by the individual class teacher.

Individual teachers were supported by colleagues and their own embracement of learning to ensure that needs such as those identified by Miller, Mitchell, and Brown (2005) were catered for: the topic-specific vocabularies of academic subjects, understandings of register and genre, cultural backgrounds to scaffold their understanding, social understandings of how to ‘be’ in the classroom, and learning strategies to process content were imparted competently. Data was utilised extensively in all three levels of the decision making to inform judgments regarding teaching and learning, ensuring that individual learning goals, instructional practices and accommodations were appropriately aligned to individual students. The decision making also seemed to be based on maximising resources to support the needs of all students. Intervention for students was enacted as soon as needs were perceived, discussed and planned for and this enactment could be triggered at the individual class level, in group teacher discussions, such as year level meetings, or at the whole school level. Support was provided at multiple points for both the learner and the teacher and this support was collaboratively developed as depicted in Figure 7.5.

The unrelenting focus on the development of teams and ways of productively working in teams ensures the effectiveness of these collective decision-making processes within the school. The school had a way of working where collaborative decision making was embedded. A team of informed experts considers the specific needs of each student and this team collaborates on how best to meet the needs of the students with the current available resources.

Critical reflection

There is an acknowledged challenge: barriers need to be removed so all students are given the chance to engage with high quality education (Carter & Abawi, 2018). The inclusive practices enacted at the school featured in this chapter highlight the importance of cultural learning, not just language learning. The knowledge of how to ‘be a student’, and indeed look like one, entails many skills, behaviours, formative experiences and a great deal of knowledge (Miller, Mitchell, & Brown, 2005). Educators at Darling Heights State Primary School acknowledged that students with ESLD have much to learn but they also embraced their whole community as being capable and indeed important is this educative role. It was not merely the teacher teaching but the whole school community working as a fluid organism, operating with a way of working that embodied inclusive practices. “Education has the capacity to stimulate knowledge and understanding of the conditions and circumstances of those most vulnerable to marginalization and exclusion” (Matthews, 2008, p.35).

After watching the animations and the three scenario videos, and then reading about the process of inclusion, it is time to critically reflect and think about your thinking – engage the process of metacognition.

Watch and respond: Activity two

- Please engage in thinking about what it means to be inclusive by engaging with the critical reflection. Instructions for activity one which consists of three separate scenarios – please carefully read:

- Do NOT refresh – If you refresh your response is deleted.

- Once you complete your response you can then save as a PDF or print. If you quit out mid way through your response is lost.

- I strongly recommend you copy your response and save into a word document as you go so that you can edit this later. It also means that you can stop and return to the activity later and still have your previous response.

- This activity takes approximately 15 to 20 minutes.

- Engage here with activity two (it will open in a new tab).

In transferring your learning about inclusion into pedagogical practices in the workplace, outline what would it look like, sound like, and feel like to a new student; a new teacher; a parent; and how you would evidence inclusive practice?

Conclusion

School leaders and teachers play a vital role in supporting students, acknowledging their diversity, creating a culture where diversity is accepted within moral parameters and engaging in inclusive practices to foster optimal learning outcomes for all students. It involves advocacy and social justice where barriers to learning are recognised and where possible removed. To create an inclusive and caring culture takes time and commitment from the school community to embrace their strengths and weaknesses, and is underpinned by a willingness to learn new skills, acquire knowledge where mindsets are challenged, and develop, refine, and review processes that enable uses to make a positive difference. It was our hope in writing this chapter that your knowledge and understanding of inclusion has deepened and your passion for engaging in inclusive, socially just practices has been ignited. We leave you to ponder how an uncompromising social justice agenda can be maintained and anchored to the needs of a changing student cohort within a specific school context.

REFERENCES

Abawi, L. Carter, S. Andrews, D. & Conway, J. (2018). Inclusive schoolwide pedagogical principles: Cultural indicators in action. In O. Bernad-Cavero (Ed.), New pedagogical challenges in the 21st Century – Contributions of research in education. (pp. 33-55). DOI: 10.5772/intehopen.70358

Alexander, M. M. (2017). Transnational English language learners fighting on an unlevel playing field: high school exit exams, accommodations, and ESL status. Language policy, 16(2), 115-133.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2018). 2016 Census findings. Retrieved from http://www.abs.gov.au/websitedbs/D3310114.nsf/home/Home

Black, R., Adger, W. N., Arnell, N. W., Dercon, S., Geddes, A., & Thomas, D. (2011). The effect of environmental change on human migration. Global environmental change, 21, S3-S11.

Carter, S. & Abawi, L. (2018). Leadership, inclusion, and quality education for all. Australasian Journal of Special and Inclusive Education. doi 10.5772/66552

Forlin, C., Chambers, D., Loreman, T., Deppeler, J., & Sharma, U. (2013). Inclusive education for students with disability: A review of the best evidence in relation to theory and practice. Australia: Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth [ARACY]. Retrieved from https://www.aracy.org.au/publications-resources/command/download_file/id/246/filename/Inclusive_education_for_students_with_disability_-_A_review_of_the_best_evidence_in_relation_to_theory_and_practice.pdf

Guide, A. S. A. R. (2013). Pathways to Self-Discovery. Retrieved from https://www.google.com/search?q=Guide,+A.+S.+A.+R.,+2013+-+There+is+only+one+corner+of+the+universe+you+can+be+certain+of+improving,+and+that%27s+your+own+self&client=firefox-b&tbm=isch&tbo=u&source=univ&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjSjJTllqjfAhWOdH0KHYXWCzUQsAR6BAgBEAE&biw=1600&bih=764

Gurría, A. (2016). Remarks by Angel Gurría, Secretary-General, CEB-OECD High-Level Seminar, Paris, 17 May 2016, https://www.oecd.org/migrationinsights/the-refugee-crisis-challenges-and-responses-for-social-investment.htm (accessed 2016-06-30).

Hek, R. (2005). The experiences and needs of refugee and asylum seeking children in the UK: A literature review. Birmingham: National Evaluation of the Children’s Fund, University of Birmingham.

Henderson, A.T., & Mapp, K.L. (2002). A new wave of evidence: The impact of school, family, and community connections on student achievement. Austin, TX: Southwest Educational Development Laboratory.

Hylen, J., Van Damme, D., Mulder, F., & D’Antoni, S. (2012). Open Educational Resources: Analysis of Responses to the OECD Country Questionnaire. OECD Education Working Papers, No. 76. OECD Publishing (NJ1).

Jasinski, M. A. (2012). Helping Children to Learn at Home: A Family Project to Support Young English-Language Learners. TESL Canada Journal, 29, 224-230.

Kirk, S., Gallagher, J. Coleman, M. R., & Anastasiow, N. (2012). Educating Exceptional

Children. (13th ed.). Wadsworth, Canada: Cengage Learning.

Lusk, M., McCallister, J., & Villalobos, G. (2013). Mental health among Mexican refugees fleeing violence and trauma. Social Development Issues, 35(3), 1-17.

Maclean, R. (2017). (Ed). Life in schools and classrooms: Past present and future. Gateway East, Singapore: Springer Nature.

Matthews, J. (2008). Schooling and settlement: Refugee education in Australia. International studies in sociology of education, 18(1), 31-45.

McLeskey, J., Rosenberg, M., & Westling, D. (2013). Inclusion effective practices for all students. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.

McLeskey, J., & Waldron, N. L. (2002). School change and inclusive schools: Lessons learned from practice [Electronic version]. Phi Delta Kappan, 84(1), 65-72.

Menken, K., & García, O. (Eds.). (2010). Negotiating language policies in schools: Educators as policymakers. New York: Routledge.

Miller, J., Mitchell, J., & Brown, J. (2005). African refugees with interrupted schooling in the high school mainstream: Dilemmas for teachers.

Ministerial Council on Education, Employment, Training and Youth Affairs (MCEETYA) (2008). Melbourne declaration on educational goals for young Australians. Retrieved from http://www.curriculum.edu.au/verve/_resources/National_Declaration_on_the_Educational_Goals_for_Young_Australians.pdf

Ni Laoire, C., Carpena-Mendez, F., Tyrell, N., White, A. (2011). Childhood and Migration in Europe: Portraits of Mobility, Identity and Belonging in Contemporary Ireland. Ashgate Publishing: Surrey, UK.

Orellana, M. (2009). Translating Childhoods: Immigrant Youth, Language an345d Culture. Rutgers University Press: New Brumswick, NJ.

Principal, (2017). Interview data, unpublished.

Queensland Department of Education, (2018). Inclusive education policy and statement booklet. Queensland Department of Education. Retrieved 8th of October, 2018 from https://education.qld.gov.au/student/inclusive-education/Documents/policy-statement-booklet.pdf#search=Inclusion

Roberts, J. (2016). Language teacher education. Routledge.

Rutter, J. (2006). Refugee children in the UK. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Sime, D., & Fox, R. (2015). Migrant children, social capital and access to services post‐migration: Transitions, negotiations and complex agencies. Children & Society, 29(6), 524-534.

Smith, D.D. & Tyler, N.C. (2011). Effective inclusive education: Equipping education professionals with necessary skills and knowledge. Prospects, 41(3), 323-339.

West, S. (2004). School’s in for Australia’s refugee students. Principal Matters 61: 30–2.

White, A. (2011). Polish Families and Migration Since EU Accession. Polity Press: Bristol.

Media Resource Title: Activity one – Inclusive teaching Practices. (2018). Australia, University of Southern Queensland (USQ). Retrieved from

Media Resource Title: Activity two – Critical Reflection. (2018). Australia, University of Southern Queensland (USQ). Retrieved from https://lor.usq.edu.au/usq/file/f27deb3c-b0c5-4381-8c82-58b20371cfaf/1/html.zip/html/index.html?activity=2