8.1 Intercultural communication

We may be tempted to think of intercultural communication as interaction between two people from different countries. While two distinct national passports communicate a key part of our identity non-verbally, what happens when two people from two different parts of the same country communicate? Indeed, intercultural communication happens between subgroups of the same country. Whether it be the distinctions between dialects in the same language, the differences in perspective between an Eastern Canadian and a Western Canadian, or the rural- versus-urban dynamic, our geographic, linguistic, educational, sociological, and psychological traits influence our communication.

Culture is part of the very fabric of our thought, and we cannot separate ourselves from it, even as we leave home and begin to define ourselves in new ways through work and achievements. Every business or organization has a culture, and within what may be considered a global culture, there are many subcultures or co-cultures. For example, consider the difference between the sales and accounting departments in a corporation. We can quickly see two distinct groups with their own symbols, vocabulary, and values. Within each group there may also be smaller groups, and each member of each department comes from a distinct background that in itself influences behaviour and interaction.

Suppose we have a group of students who are all similar in age and educational level. Do gender and the societal expectations of roles influence interaction? Of course! There will be differences on multiple levels.

More than just the clothes we wear, the movies we watch, or the video games we play, all representations of our environment are part of our culture. Culture also involves the psychological aspects and behaviours that are expected of members of our group. From the choice of words (message), to how we communicate (in person or by e-mail), to how we acknowledge understanding with a nod or a glance (non-verbal feedback), to the internal and external interference, all aspects of communication are influenced by culture.

Defining culture

Culture consists of the shared beliefs, values, and assumptions of a group of people who learn from one another and teach to others that their behaviours, attitudes, and perspectives are the correct ways to think, act, and feel.

It is helpful to think about culture in the following five ways:

- Culture is learned.

- Culture is shared.

- Culture is dynamic.

- Culture is systemic.

- Culture is symbolic.

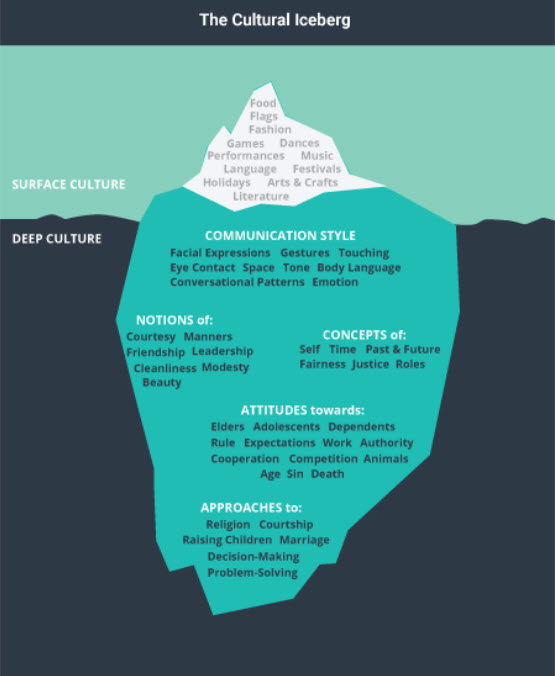

The iceberg (shown in Figure 7.5.1), is a commonly used metaphor to describe culture and is great for illustrating the tangible and the intangible. When talking about culture, most people focus on the “tip of the iceberg,” which is visible but makes up just 10 percent of the object. The rest of the iceberg, 90 percent of it, is below the waterline.

Figure 7.51 The cultural iceberg (by Laura Underwood), adapted from Lindner (2013)

Many business leaders, when addressing intercultural situations, pick up on the things they can see—things on the “tip of the iceberg.” Things like food, clothing, and language difference are easily and immediately obvious, but focusing only on these can mean missing or overlooking deeper cultural aspects such as thought patterns, values, and beliefs that are under the surface. Solutions to any interpersonal miscommunication that results become temporary bandages covering deeply rooted conflicts.

Multicultural, cross-cultural, and intercultural communication

Although they are often used interchangeably, it is important to note the distinctions between the terms multicultural, cross-cultural, and intercultural communication.

Multiculturalism is a rather surface approach to the coexistence and tolerance of different cultures. It takes the perspective of “us and the others” and typically focuses on those tip-of-the-iceberg features of culture, thus highlighting and accepting some differences but maintaining a “safe” distance. If you have a multicultural day at work, for example, it usually will feature some food, dance, dress, or maybe learning about how to say a few words or greetings in a sampling of cultures.

Cross-cultural approaches typically go a bit deeper, the goal being to be more diplomatic or sensitive. They account for some interaction and recognition of difference through trade and cooperation, which builds some limited understanding—such as, for instance, bowing instead of shaking hands, or giving small but meaningful gifts. A common drawback of cross-cultural comparisons is that we can wade into stereotyping and ethnocentric attitudes—judging other cultures by our own cultural standards—if we aren’t mindful.

Lastly, when we look at intercultural approaches, we are well beneath the surface of the iceberg, intentionally making efforts to better understand other cultures as well as ourselves. An intercultural approach is not easy and is often messy, but when you get it right, it is usually far more rewarding than the other two approaches. The intercultural approach is difficult and effective for the same reasons; it acknowledges complexity and aims to work through it to a positive, inclusive, and equitable outcome.

Whenever we encounter someone, we notice similarities and differences. While both are important, it is often the differences that contribute to communication troubles. We don’t see similarities and differences only on an individual level. In fact, we also place people into in-groups and out-groups based on the similarities and differences we perceive. We tend to react to someone we perceive as a member of an out-group based on the characteristics we attach to the group rather than the individual (Allen, 2010). In these situations, it is more likely that stereotypes and prejudice will influence our communication. This division of people into opposing groups has been the source of great conflict around the world, and learning about difference and why it matters will help us be more competent communicators and help to prevent conflict.

Theories of cross-cultural communication

Hofstede

Social psychologist Geert Hofstede (Hofstede, 1982, 2001, 2005) is one of the most well-known researchers in cross-cultural communication and management. Hofstede’s theory places cultural dimensions on a continuum that range from high to low and really only make sense when the elements are compared to another culture. Hofstede’s dimensions include the following:

- Power distance: High power distance means a culture accepts and expects a great deal of hierarchy; low power distance means the president and janitor could be on the same level.

- Individualism: High individualism means that a culture tends to put individual needs ahead of group or collective needs.

- Uncertainty avoidance: High uncertainty avoidance means a culture tends to go to some lengths to be able to predict and control the future. Low uncertainty avoidance means the culture is more relaxed about the future, which sometimes shows in being willing to take risks.

- Masculinity: High masculinity relates to a society valuing traits that were traditionally considered masculine, such as competition, aggressiveness, and achievement. A low masculinity score demonstrates traits that were traditionally considered feminine, such as cooperation, caring, and quality of life.

- Long-term orientation: High long-term orientation means a culture tends to take a long- term, sometimes multi-generational view when making decisions about the present and the future. Low long-term orientation is often demonstrated in cultures that want quick results and that tend to spend instead of save.

- Indulgence: High indulgence means cultures that are okay with people indulging their desires and impulses. Low indulgence or restraint-based cultures value people who control or suppress desires and impulses.

These tools can provide wonderful general insight into making sense of understanding differences and similarities across key below-the-surface cross-cultural elements, but remember that people are still individuals and may or may not conform to what’s listed in the tools.

Trompenaars

Fons Trompenaars is another researcher who came up with a different set of cross-cultural measures. These are his seven dimensions of culture (The seven dimensions of culture, n.d.):

- Universalism vs. particularism: the extent that a culture is more prone to apply rules and laws as a way of ensuring fairness, in contrast to a culture that looks at the specifics of context and looks at who is involved, to ensure fairness. The former puts the task first; the latter puts the relationship first.

- Individualism vs. communitarianism: the extent that people prioritize individual interests versus the community’s interest.

- Specific vs. diffuse: the extent that a culture prioritizes a head-down, task-focused approach to doing work, versus an inclusive, overlapping relationship between life and work.

- Neutral vs. emotional: the extent that a culture works to avoid showing emotion versus a culture that values a display or expression of emotions.

- Achievement vs. ascription: the degree to which a culture values earned achievement in what you do versus ascribed qualities related to who you are based on elements like title, lineage, or position.

- Sequential time vs. synchronous time: the degree to which a culture prefers doing things one at time in an orderly fashion versus preferring a more flexible approach to time with the ability to do many things at once.

- Internal direction vs. outer direction: the degree to which members of a culture believe they have control over themselves and their environment versus being more conscious of how they need to conform to the external environment.

Like Hofstede’s work, Trompenaars’ dimensions help us understand some of those beneath-the-surface-of-the-iceberg elements of culture. It’s equally important to understand our own cultures as it is to look at others, always being mindful that our cultures, as well as others, are made up of individuals.

High context and low context cultures

High context cultures are replete with implied meanings beyond the words on the surface and even body language that may not be obvious to people unfamiliar with the context. Low context cultures are typically more direct and tend to use words to attempt to convey precise meaning.

For example, an agreement in a high context culture might be verbal because the parties know each other’s families, histories, and social position. This knowledge is sufficient for the agreement to be enforced. No one actually has to say, “I know where you live. If you don’t hold up your end of the bargain, …” because the shared understanding is implied and highly contextual. A low context culture usually requires highly detailed, written agreements that are signed by both parties, sometimes mediated through specialists like lawyers, as a way to enforce the agreement. This is low context because the written agreement spells out all the details so that not much is left to the imagination or “context.”

Working with others

How can you prepare to work with people from cultures different than your own? Start by doing your homework. Let’s assume that you have a group of Japanese colleagues visiting your office next week. How could you prepare for their visit? If you’re not already familiar with the history and culture of Japan, this is a good time to do some reading or a little bit of research online. If you can find a few English-language publications from Japan (such as newspapers and magazines), you may wish to read through them to become familiar with current events and gain some insight into the written communication style used.

Preparing this way will help you to avoid mentioning sensitive topics and to show correct etiquette to your guests. For example, Japanese culture values modesty, politeness, and punctuality, so with this information, you can make sure you are early for appointments and do not monopolize conversations by talking about yourself and your achievements. You should also find out what faux pas to avoid. For example, in company of Japanese people, it is customary to pour others’ drinks (another person at the table will pour yours). Also, make sure you do not put your chopsticks vertically in a bowl of rice, as this is considered rude. If you have not used chopsticks before and you expect to eat Japanese food with your colleagues, it would be a nice gesture to make an effort to learn. Similarly, learning a few words of the language (e.g., hello, nice to meet you, thank you, and goodbye) will show your guests that you are interested in their culture and are willing to make the effort to communicate.

If you have a colleague who has traveled to Japan or has spent time in the company of Japanese colleagues before, ask them about their experience so that you can prepare. What mistakes should you avoid? How should you address and greet your colleagues? Knowing the answers to these questions will make you feel more confident when the time comes. But most of all, remember that a little goes a long way. Your guests will appreciate your efforts to make them feel welcome and comfortable. People are, for the most part, kind and understanding, so if you make some mistakes along the way, be kind to yourself. Reflect on what happened, learn from it, and move on. Most people are keen to share their culture with others, so your guests will be happy to explain various practices to you.

Improving your intercultural competence

One helpful way to develop your intercultural communication competence is to develop sensitivity to intercultural communication issues and best practices. From everything we have learned so far, it may feel complex and overwhelming. The Intercultural Development Continuum is a theory created by Mitchell Hammer (2012) that helps demystify the process of moving from monocultural approaches to intercultural approaches. There are five steps in this transition:

1. Denial: Denial is the problem-denying stage. For example, a well-meaning person might say that they pay no attention to race issues because they themselves are “colour blind” and treat everyone the same, irrespective of race. While on the surface this attitude seems fair-minded, it can mean willfully blinding oneself to very real cultural differences. Essentially, not much sensitivity or empathy can be present if one denies that cultural differences actually exist. This is a monocultural mindset. When there’s denial in organizations, diversity feels ignored.

2. Polarization: Polarization is the stage where one accepts and acknowledges that there is such a thing as cultural difference, but the difference is framed as a negative “us versus them” proposition. This usually means “we” are the good guys, and “they” are the bad guys. Sometimes a person will reverse this approach and say their own culture is bad or otherwise deficient and see a different culture as superior or very good. Either way, polarization reinforces already-existing biases and stereotypes and misses out on nuanced understanding and empathy. It is thus considered more of a monocultural mindset. When polarization exists in organizations, diversity usually feels uncomfortable.

3. Minimization: Minimization is a hybrid category that is really neither monocultural nor intercultural. Minimization recognizes that there are cultural differences, even significant ones, but tends to focus on universal commonalities that can mask or paper over other important cultural distinctions. This is typically characterized by limited cultural self-awareness in the case of a person belonging to a dominant culture, or as a strategy by members of non-dominant groups to “go along to get along” in an organization. When dominant culture minimization exists in organizations, diversity feels not heard.

4. Acceptance: Acceptance demonstrates a recognition and deeper appreciation of both their own and others’ cultural differences and commonalities and is the first dimension that exhibits a more intercultural mindset. At this level, people are better able to detect cultural patterns and able to see how those patterns make sense in their own and other cultural contexts. There is the capacity to accept others as being different and at the same time being fully human. When there is acceptance in organizations, diversity feels understood.

5. Adaptation: Adaptation is characterized by an ability not only to recognize different cultural patterns in oneself and other cultures but also to effectively adapt one’s mindset or behaviour to suit the cultural context in an authentic way. When there is adaptation in organizations, diversity feels valued and involved.

The first two steps out of five reflect monocultural mindsets. According to Hammer (2009), people who belong to dominant cultural groups in a given society or people who have had very little exposure to other cultures may be more likely to have a worldview that’s more monocultural. But how does this cause problems in interpersonal communication? For one, being blind to the cultural differences of the person you want to communicate with (denial) increases the likelihood that you will encode a message that they won’t decode the way you anticipate, or vice versa.

For example, let’s say culture A considers the head a special and sacred part of the body that others should never touch, certainly not strangers or mere acquaintances. But let’s say in your culture, people sometimes pat each other on the head as a sign of respect and caring. So you pat your culture A colleague on the head, and this act sets off a huge conflict.

It would take a great deal of careful communication to sort out such a misunderstanding, but if each party keeps judging the other by their own cultural standards, it’s likely that additional misunderstanding, conflict, and poor communication will transpire.

Using this example, polarization can come into play because now there’s a basis of experience for selective perception of the other culture. Culture A might say that your culture is disrespectful, lacks proper morals, and values, and it might support these claims with anecdotal evidence of people from your culture patting one another on the sacred head!

Meanwhile, your culture will say that culture A is bad-tempered, unintelligent, and angry by nature and that there would be no point in even trying to respect or explain things them.

It’s a simple example, but over time and history, situations like this have mounted and thus led to violence, war, and genocide.

According to Hammer (2009), the majority of people who have taken the IDI inventory, a 50- question questionnaire to determine where they are on the monocultural–intercultural continuum, fall in the category of minimization, which is neither monocultural nor intercultural. It’s the middle-of-the-road category that on one hand recognizes cultural difference but on the other hand simultaneously downplays it. While not as extreme as the first two situations, interpersonal communication with someone of a different culture can also be difficult here because of the same encoding/decoding issues that can lead to inaccurate perceptions. On the positive side, the recognition of cultural differences provides a foundation on which to build and a point from which to move toward acceptance, which is an intercultural mindset.

There are fewer people in the acceptance category than there are in the minimization category, and only a small percentage of people fall into the adaptation category. This means most of us have our work cut out for us if we recognize the value—considering our increasingly global societies and economies—of developing an intercultural mindset as a way to improve our interpersonal communication skill.

References

Allen, B. (2010). Difference matters: Communicating social identity. Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press.

Hammer, M.R. (2009). The Intercultural Development Inventory. In M.A. Moodian (Ed.). Contemporary leadership and intercultural competence. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Hofstede, G. (1982). Culture’s consequences. (2nd ed.). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions, and organizations across nations (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Hofstede, G. (2005). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind. (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Lindner, M. (2013). Edward T. Hall’s cultural iceberg. Prezi presentation retrieved from https://prezi.com/y4biykjasxhw/edward-t-halls-cultural-iceberg/?utm_source=prezi-view&utm_medium=ending-bar&utm_content=Title-link&utm_campaign=ending-bar-tryout.

The seven dimensions of culture: Understanding and managing cultural differences. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.mindtools.com/pages/article/seven-dimensions.htm.

Attribution

This chapter is an adaptation of Part 4: Interpersonal communication in the professional environment in Professional Communications OER by the Olds College OER Development Team and is used under a CC-BY 4.0 International license. You can download this book for free at http://www.procomoer.org/.