3. Engaging Stakeholders & Exploring Key Skills for Project Managers

Learning Objectives

- Identify various stakeholders involved in a typical project

- Discuss why the sponsor is the key ingredient to the successful completion of the project

- Describe personal characteristics that suit project-management duties

- Outline the skills required to lead and manage individuals and project teams effectively

- Recognize the value of communication in conflict management, negotiation, facilitation, problem solving, giving and receiving feedback

- Manage differences effectively – leading cross functional, cross cultural and virtual projects

- Examine the concepts of Emotional Intelligence, Personality Types and Leadership Styles

- Determine the type of Team that is best suited for the project

- Discuss The role of Project Culture in Project Management

Project Stakeholders

A project is successful when it achieves its objectives and meets or exceeds the expectations of the stakeholders. But who are the stakeholders? Stakeholders are individuals who either care about or have a vested interest in your project. They are the people who are actively involved with the work of the project or have something to either gain or lose as a result of the project. When you manage a project to add lanes to a highway, motorists are stakeholders who are positively affected. However, you negatively affect residents who live near the highway during your project (with construction noise) and after your project with far-reaching implications (increased traffic noise and pollution).

The project sponsor, generally an executive in the organization with the authority to assign resources and enforce decisions regarding the project, is a stakeholder. The customer, subcontractors, suppliers, and sometimes even the government are stakeholders. The project manager, project team members, and the managers from other departments in the organization are stakeholders as well. It’s important to identify all the stakeholders in your project upfront. Leaving out important stakeholders or their department’s function and not discovering the error until well into the project could be a project killer.

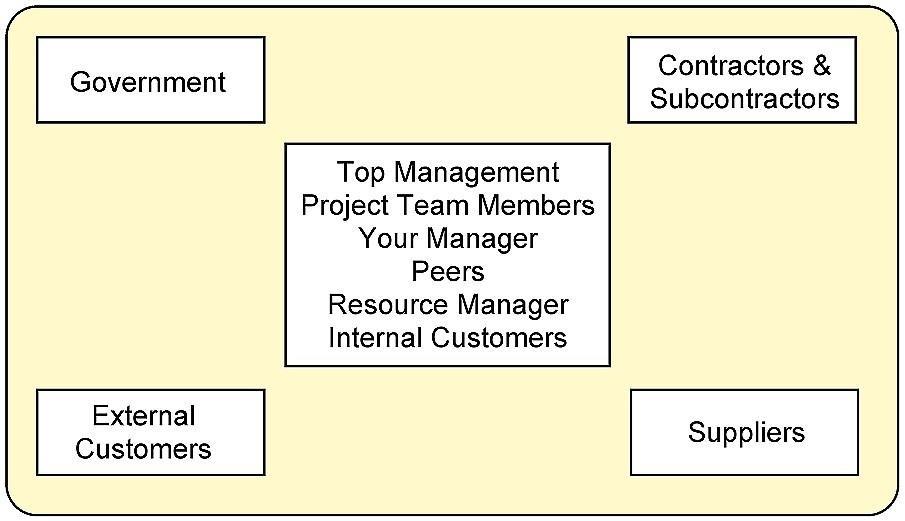

Figure 3.1 shows a sample of the project environment featuring the different kinds of stakeholders involved on a typical project. A study of this diagram confronts us with a couple of interesting facts.

- First, the number of stakeholders that project managers must deal with ensures that they will have a complex job guiding their project through the life cycle. Problems with any of these members can derail the project.

- Second, the diagram shows that project managers have to deal with people external to the organization as well as the internal environment, certainly more complex than what a manager in an internal environment faces. For example, suppliers who are late in delivering crucial parts may blow the project schedule. To compound the problem, project managers generally have little or no direct control over any of these individuals.

Let’s take a look at these Project Stakeholders and their relationships to the project manager.

Top Management

Top management may include the president of the company, vice-presidents, directors, division managers, the corporate operating committee, and others. These people direct the strategy and development of the organization.

On the plus side, you are likely to have top management support, which means it will be easier to recruit the best staff to carry out the project, and acquire needed material and resources; also visibility can enhance a project manager’s professional standing in the company.

On the other side, failure can be quite dramatic and visible to all, and if the project is large and expensive (most are), the cost of failure will be more substantial than for a smaller, less visible project.

Some suggestions in dealing with top management are:

- Develop in-depth plans and major milestones that must be approved by top management during the planning and design phases of the project.

- Ask top management associated with your project for their information reporting needs and frequency.

- Develop a status reporting methodology to be distributed on a scheduled basis.

- Keep them informed of project risks and potential impacts at all times.

The Project Team

The project team is made up of those people dedicated to the project. The team can include contracted or borrowed team members who work full-time or on a part-time basis. As project manager, you need management skills, such as planning, organizing, leading and controlling (POLC) to provide leadership, direction, and above all, support your team members as they go about accomplishing their tasks. Working closely with the team to solve problems can help you learn from the team and build rapport. Showing your support for the project team and for each member will help you get their support and cooperation.

Here are some difficulties you may encounter in dealing with project team members:

- Because project team members are borrowed and they don’t report to you, their priorities may be elsewhere.

- They may be juggling many projects as well as their full-time job and have difficulty meeting deadlines.

- Personality conflicts may arise. These may be caused by differences in social style or values or they may be the result of some bad experience when people worked together in the past.

- You may find out about missed deadlines when it is too late to recover.

Managing project team members requires interpersonal skills. Here are some suggestions that can help:

- Involve team members in project planning.

- Arrange to meet privately and informally with each team member at several points in the project, perhaps for lunch or coffee.

- Be available to hear team members’ concerns at any time.

- Encourage team members to pitch in and help others when needed.

- Complete a project performance review for team members.

Check Your Understanding

Your Manager

Typically the boss decides what the assignment is and who can work with the project manager on projects. Keeping your manager informed will help ensure that you get the necessary resources to complete your project.

If things go wrong on a project, it is nice to have an understanding and supportive boss to go to bat for you if necessary. By supporting your manager, you will find your manager will support you more often.

Communication tips:

- Find out exactly how your performance will be measured.

- When unclear about directions, ask for clarification.

- Develop a reporting schedule that is acceptable to your boss.

- Communicate frequently.

Peers

Peers are people who are at the same level in the organization as you and may or may not be on the project team. These people will also have a vested interest in the product. However, they will have neither the leadership responsibilities nor the accountability for the success or failure of the project that you have.

Your relationship with peers can be impeded by:

- Inadequate control over peers

- Political maneuvering or sabotage

- Personality conflicts or technical conflicts

- Envy because your peer may have wanted to lead the project

- Conflicting instructions from your manager and your peer’s manager.

Peer support is essential. Because most of us serve our self-interest first, use some investigating, selling, influencing, and politicking skills here. To ensure you have cooperation and support from your peers:

- Get the support of your project sponsor or top management to empower you as the project manager with as much authority as possible. It’s important that the sponsor makes it clear to the other team members that their cooperation on project activities is expected.

- Confront your peer if you notice a behaviour that seems dysfunctional, such as bad-mouthing the project.

- Be explicit in asking for full support from your peers. Arrange for frequent review meetings.

- Establish goals and standards of performance for all team members.

Resource Managers

Because project managers are in the position of borrowing resources, other managers control their resources. So their relationships with people are especially important. If their relationship is good, they may be able to consistently acquire the best staff and the best equipment for their projects. If relationships aren’t good, they may find themselves not able to get good people or equipment needed on the project.

Internal Customers

Internal customers are individuals within the organization who are customers for projects that meet the needs of internal demands. The customer holds the power to accept or reject your work. Early in the relationship, the project manager will need to negotiate, clarify, and document project specifications and deliverable. After the project begins, the project manager must stay tuned in to the customer’s concerns and issues and keep the customer informed.

Common stumbling blocks – what would you do?

External Customers

External customers are the customers when projects could be marketed to outside customers. In the case of Ford Motor Company, for example, the external customers would be the buyers of the automobiles. Also if you are managing a project at your company for Ford Motor Company, they will be your external customer.

Government

Project managers working in certain heavily regulated environments (e.g., pharmaceutical, banking, or military industries) will have to deal with government regulators and departments. These can include all or some levels of government from municipal, provincial, federal, to international.

Contractors, Subcontractors and Suppliers

There are times when organizations don’t have the expertise or resources available in-house, and work is farmed out to contractors or subcontractors. This can be a construction management foreman, network consultant, electrician, carpenter, architect, or anyone who is not an employee. Managing contractors or suppliers requires many of the skills needed to manage full-time project team members.

Any number of problems can arise with contractors or subcontractors:

- Quality of the work

- Cost overruns

- Schedule slippage

Many projects depend on goods provided by outside suppliers. This is true for example of construction projects where lumber, nails, bricks, and mortar come from outside suppliers. If the supplied goods are delivered late or are in short supply or of poor quality or if the price is greater than originally quoted, the project may suffer.

Depending on the project, managing contractor and supplier relationships can consume more than half of the project manager’s time. It is not purely intuitive; it involves a sophisticated skill set that includes managing conflicts, negotiating, and other interpersonal skills.

Politics of Projects

Many times, project stakeholders have conflicting interests. It’s the project manager’s responsibility to understand these conflicts and try to resolve them. It’s also the project manger’s responsibility to manage stakeholder expectations. Be certain to identify and meet with all key stakeholders early in the project to understand all their needs and constraints.

Project managers are somewhat like politicians. Typically, they are not inherently powerful or capable of imposing their will directly on coworkers, subcontractors, and suppliers. Like politicians, if they are to get their way, they have to exercise influence effectively over others. On projects, project managers have direct control over very few things; therefore their ability to influence others – to be a good politician – may be very important

Here are a few steps a good project politician should follow. However, a good rule is that when in doubt, stakeholder conflicts should always be resolved in of the customer.

Steps

Culture of Stakeholders

When project stakeholders do not share a common culture, project management must adapt its organizations and work processes to cope with cultural differences. The following are three major aspects of cultural difference that can affect a project:

- Communications

- Negotiations

- Decision making

Communication is perhaps the most visible manifestation of culture. Project managers encounter cultural differences in communication in language, context, and candor.

Language is clearly the greatest barrier to communication. When project stakeholders do not share the same language, communication slows down and is often filtered to share only information that is deemed critical.

The barrier to communication can influence project execution where quick and accurate exchange of ideas and information is critical.

The interpretation of information reflects the extent that context and candor influence cultural expressions of ideas and understanding of information. In some cultures, an affirmative answer to a question does not always mean yes. The cultural influence can create confusion on a project where project stakeholders represent more than one culture.

Not all cultural differences are related to international projects. Corporate cultures and even regional differences can create cultural confusion on a project.

Managing Stakeholders

Often there is more than one major stakeholder in the project. An increase in the number of stakeholders adds stress to the project and influences the project’s complexity level. The business or emotional investment of the stakeholder in the project and the ability of the stakeholder to influence the project outcomes or execution approach will also influence the stakeholder complexity of the project. In addition to the number of stakeholders and their level of investment, the degree to which the project stakeholders agree or disagree influences the project’s complexity.

A small commercial construction project will typically have several stakeholders. All the building permitting agencies, environmental agencies, and labor and safety agencies have an interest in the project and can influence the execution plan of the project. The neighbors will have an interest in the architectural appeal, the noise, and the purpose of the building.

Relationship Building Tips

Take the time to identify all stakeholders before starting a new project. Include those who are impacted by the project, as well as groups with the ability to impact the project. Then, begin the process of building strong relationships with each one using the following method.

These are the basics of building strong stakeholder relationships. But as in any relationship, there are subtleties that every successful project manager understands – such as learning the differences between and relating well to different types stakeholders.

How to Relate to Different Types of Stakeholders

By conducting a stakeholder analysis, project managers can gather enough information on which to build strong relationships – regardless of the differences between them. For example, the needs and wants of a director of marketing will be different from those of a chief information officer. Therefore, the project manager’s engagement with each will need to be different as well.

Stakeholders with financial concerns will need to know the potential return of the project’s outcomes. Others will support projects if there is sound evidence of their value to improving operations, boosting market share, increasing production, or meeting other company objectives.

Keep each stakeholder’s expectations and needs in mind throughout each conversation, report or email, no matter how casual or formal the communication may be. Remember that the company’s interests are more important than any individual’s – yours or a stakeholder’s. When forced to choose between them, put the company’s needs first.

No matter what their needs or wants, all stakeholders will respect the project manager who:

- Is always honest, even when telling them something they don’t want to hear

- Takes ownership of the project

- Is predictable and reliable

- Stands by his or her decisions

- Takes accountability for mistakes

Supportive Stakeholders are Essential to Project Success

Achieving a project’s objectives takes a focused, well-organized project manager who can engage with a committed team and gain the support of all stakeholders. Building strong, trusting relationships with interested parties from the start can make the difference between project success and failure.

Culture and Project Management

When working with internal and external customers on a project, it is essential to pay close attention to relationships, context, history, and the corporate culture. Corporate culture refers to the beliefs, attitudes, and values that the organization’s members share and the behaviours consistent with them (which they give rise to). Corporate culture sets one organization apart from another, and dictates how members of the organization will see you, interact with you, and sometimes judge you. Often, projects too have a specific culture, work norms, and social conventions.

Some aspects of corporate culture are easily observed; others are more difficult to discern. You can easily observe the office environment and how people dress and speak. In one company, individuals work separately in closed offices; in another, teams may work in a shared environment. The more subtle components of corporate culture, such as the values and overarching business philosophy, may not be readily apparent, but they are reflected in member behaviours, symbols, and conventions used.

Project Manager’s Checklist

Once the corporate culture has been identified, members should try to adapt to the frequency, formality, and type of communication customary in that culture. This adaptation will strongly affect project members’ productivity and satisfaction internally and externally. Consider the following:

- Which stakeholders will make the decision in this organization on this issue? Will your project decisions and documentation have to go up through several layers to get approval? If so, what are the criteria and values that may affect acceptance there? For example, is being on schedule the most important consideration? Cost? Quality?

- What type of communication among and between stakeholders is preferred? Do they want lengthy documents? Is “short and sweet” the typical standard?

- What medium of communication is preferred? What kind of medium is usually chosen for this type of situation? Check the files to see what others have done. Ask others in the organization.

- What vocabulary and format are used? What colors and designs are used (e.g., at Hewlett-Packard, all rectangles have curved corners)?

Project Team Challenges

Today’s globally distributed organizations (and projects) consist of people who have differing “worldviews.” Worldview is a looking glass through which people see the world as Bob Shebib describes: “[It is] a belief system about the nature of the universe, its perceived effect on human behaviour, and one’s place in the universe. Worldview is a fundamental core set of assumptions explaining cultural forces, the nature of humankind, the nature of good and evil, luck, fate, spirits, the power of significant others, the role of time, and the nature of our physical and natural resources” (Shebib, 2003, p. 296).

In most situations, there is simply no substitute for having a well-placed person from the host culture to guide the new person through the cultural nuances of getting things done. In fact, if this “intervention” isn’t present, it is likely to affect the person’s motivation or desire to continue trying to break through the cultural (and other) barriers. Indeed, optimal effectiveness in such situations requires learning of cultures in developing countries or international micro-cultures and sharing perceptions among the culturally diverse task participants on how to get things done. Project leaders require sensitivity and awareness of multicultural preferences. The following broad areas should be considered:

- Individual identity and role within the project versus family of origin and community

- Verbal and emotional expressiveness

- Relationship expectations

- Style of communication

- Language

- Personal priorities, values, and beliefs

- Time orientation

- Working with Individuals

The Project Manager – Engaging with the Team

Working with other people involves dealing with them both logically and emotionally. A successful working relationship between individuals begins with appreciating the importance of emotions and how they relate to personality types, leadership styles, negotiations, and setting goals.

Emotional Intelligence

Emotions are both a mental and physiological response to environmental and internal stimuli. Leaders need to understand and value their emotions to appropriately respond to the client, project team, and project environment.

Emotional intelligence includes the following:

- Self-awareness

- Self-regulation

- Empathy

- Relationship management

Emotions are important to generating energy around a concept, building commitment to goals, and developing high-performing teams. Emotional intelligence is an important part of the project manager’s ability to build trust among the team members and with the client. It is an important factor in establishing credibility and an open dialogue with project stakeholders. Emotional intelligence is critical for project managers, and the more complex the project profile, the more important the project manager’s emotional intelligence becomes to project success.

Personality Types

Personality types refer to the differences among people in such matters as what motivates them, how they process information, how they handle conflict, etc. Understanding people’s personality types is acknowledged as an asset in interacting and communicating with them more effectively. Understanding your personality type as a project manager will assist you in evaluating your tendencies and strengths in different situations.

Understanding others’ personality types can also help you coordinate the skills of your individual team members and address the various needs of your client.

The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) is one of most widely used tools for exploring personal preference, with more than two million people taking the MBTI each year. The MBTI is often referred to as simply the Myers-Briggs. It is a tool that can be used in project management training to develop awareness of preferences for processing information and relationships with other people.

The Myers-Briggs identifies 16 personality types based on four preferences derived from the questionnaire. The preferences are between pairs of opposite characteristics and include the following:

- Extroversion (E)-Introversion (I)

- Sensing (S)-Intuition (N)

- Thinking (T)-Feeling (F)

- Judging (J)-Perceiving (P)

Sixteen Myers-Briggs types can be derived from the four dichotomies. Each of the 16 types describes a preference: for focusing on the inner or outer world (E-I), for approaching and internalizing information (S-I), for making decisions (T-F), and for planning (J-P). For example, an ISTJ is a Myers-Briggs type who prefers to focus on the inner world and basic information, prefers logic, and likes to decide quickly.

Take a free 16 Personalities Test … What type are you?

It is important to note that there is no best type and that effective interpretation of the Myers-Briggs requires training. The purpose of the Myers-Briggs is to understand and appreciate the differences among people. This understanding can be helpful in building the project team, developing common goals, and communicating with project stakeholders. For example, different people process information differently. Extroverts prefer face-to-face meetings as the primary means of communicating, while introverts prefer written communication. Sensing types focus on facts, and intuitive types want the big picture.

On larger, more complex projects, some project managers will use the Myers-Briggs as a team-building tool during project start-up. This is typically a facilitated work session where team members take the Myers-Briggs and share with the team how they process information, what communication approaches they prefer, and what decision-making preferences they have. This allows the team to identify potential areas of conflict, develop communication strategies, and build an appreciation for the diversity of the team.

Leadership

Understanding the differences among people is a critical leadership skill. This includes understanding how people process information, how different experiences influence the way people perceive the environment, and how people develop filters that allow certain information to be incorporated while other information is excluded. The more complex the project, the more important the understanding of how people process information, make decisions, and deal with conflict. There are many personality-type tests that have been developed and explore different aspects of people’s personalities. It might be prudent to explore the different tests available and utilize those that are most beneficial for your team.

Leadership Styles

Leadership style is a function of both the personal characteristics of the leader and the environment in which the leadership must occur, and a topic that several researchers have attempted to understand. Robert Tannenbaum and Warren Schmidt described leaders as either autocratic or democratic[1]. Harold Leavitt described leaders as pathfinders (visionaries), problem solvers (analytical), or implementers (team oriented)[2]. James MacGregor Burns conceived leaders as either transactional (focused on actions and decisions) or transformational (focused on the long-term needs of the group and organization)[3].

Fred Fiedler introduced his contingency theory, which is the ability of leaders to adapt their leadership approach to the environment[4]. Most leaders have a dominant leadership style that is most comfortable for them. For example, most engineers spend years training in analytical problem solving and often develop an analytical approach to leadership.

A leadership style reflects personal characteristics and life experiences. Although a project manager’s leadership style may be predominantly a pathfinder, most project managers become problem solvers or implementers when they perceive the need for these leadership approaches. The leadership approach incorporates the dominant leadership style and Fiedler’s contingency focus on adapting to the project environment.

No particular leadership approach is specifically appropriate for managing a project. Due to the unique circumstances inherent in each project, the leadership approach and the management skills required to be successful vary depending on the complexity profile of the project. However, the Project Management Institute published Shi and Chen’s research that studied project management leadership traits and concluded that good communication skills and the ability to build harmonious relationships and motivate others are essential[5]. Beyond this broad set of leadership skills, the successful leadership approach will depend on the profile of the project. For example, a transactional project manager with a strong command-and-control leadership approach may be very successful on a small software development project or a construction project, where tasks are clear, roles are well understood, and the project environment is cohesive. This same project manager is less likely to be successful on a larger, more complex project with a diverse project team and complicated work processes.

Matching the appropriate leadership style and approach to the complexity profile of the project is a critical element of project success. Even experienced project managers are less likely to be successful if their leadership approach does not match the complexity profile of the project.

Each project phase may also require a different leadership approach. During the start-up phase of a project, when new team members are first assigned to the project, the project may require a command-and-control leadership approach. Later, as the project moves into the conceptual phase, creativity becomes important, and the project management takes on a more transformational leadership approach. Most experienced project managers are able to adjust their leadership approach to the needs of the project phase. Occasionally, on very large and complex projects, some companies will bring in different project managers for various phases of a project. Changing project managers may bring the right level of experience and the appropriate leadership approach, but is also disruptive to a project. Senior management must balance the benefit of matching the right leadership approach with the cost of disrupting established relationships.

Example: Multinational Textbook Publishing Project

On a project to publish a new textbook at a major publisher, a project manager led a team that included members from partners that were included in a joint venture. The editorial manager was Greek, the business manager was German, and other members of the team were from various locations in the United States and Europe. In addition to the traditional potential for conflict that arises from team members from different cultures, the editorial manager and business manager were responsible for protecting the interest of their company in the joint venture.

The project manager held two alignment or team-building meetings. The first was a two-day meeting held at a local resort and included only the members of the project leadership team. An outside facilitator was hired to facilitate discussion, and the topic of cultural conflict and organizational goal conflict quickly emerged. The team discussed several methods for developing understanding and addressing conflicts that would increase the likelihood of finding mutual agreement.

The second team-building session was a one-day meeting that included the executive sponsors from the various partners in the joint venture. With the project team aligned, the project manager was able to develop support for the publication project’s strategy and commitment from the executives of the joint venture. In addition to building processes that would enable the team to address difficult cultural differences, the project manager focused on building trust with each of the team members. The project manager knew that building trust with the team was as critical to the success of the project as the technical project management skills and devoted significant management time to building and maintaining this trust.

Adjusting Leadership Styles

Remember that personality traits reflect an individual’s preferences, not their limitations. It is important to understand that individuals can still function in situations for which they are not best suited. It is also important to realize that you can change your leadership style according to the needs of your team and the particular project’s attributes and scope.

For example, a project leader who is more thinking (T) than feeling (F) (according to the Myers-Briggs model) would need to work harder to be considerate of how team members who are more feeling (F) might react if they were singled out in a meeting because they were behind schedule. If individuals knows their own preferences and which personality types are most successful in each type of project or project phase, they can set goals for improvement in their ability to perform in those areas that are not their natural preference.

Another individual goal is to examine which conflict resolution styles you are least comfortable and work to improve those styles so that they can be used when they are more appropriate than your default style.

Leadership Skills

The project manager must be perceived to be credible by the project team and key stakeholders. A successful project manager can solve problems and has a high degree of tolerance for ambiguity. On projects, the environment changes frequently, and the project manager must apply the appropriate leadership approach for each situation.

The successful project manager must have good communication skills. All project problems are connected to skills needed by the project manager:

- Breakdown in communication represents the lack of communication skills

- Uncommitted team members represents the lack of team-building skills

- Role confusion represents the lack of organizational skills.

Project managers need a large numbers of skills. These skills include administrative skills, organizational skills, and technical skills associated with the technology of the project. The types of skills and the depth of the skills needed are closely connected to the complexity profile of the project. Typically on smaller, less complex projects, project managers need a greater degree of technical skill. On larger, more complex projects, project managers need more organizational skills to deal with the complexity. On smaller projects, the project manager is intimately involved in developing the project schedule, cost estimates, and quality standards. On larger projects, functional managers are typically responsible for managing these aspects of the project, and the project manager provides the organizational framework for the work to be successful.

Listening

One of the most important communication skills of the project manager is the ability to actively listen. Active listening is placing oneself in the speaker’s position as much as possible, understanding the communication from the point of view of the speaker, listening to the body language and other environmental cues, and striving not just to hear, but to understand. Active listening takes focus and practice to become effective. It enables a project manager to go beyond the basic information that is being shared and to develop a more complete understanding of the information.

Example: Client’s Body Language

A client from the Abu Dhabi project visited the VPD to review the progress of the project with the Senior Management Team (SMT). The project manager listened and took notes on the five concerns expressed by the Senior Management Team (SMT).

The project manager observed that the client’s body language showed more tension than usual. This was a cue to listen very carefully. The project manager nodded occasionally and clearly demonstrated he was listening through his posture, small agreeable sounds, and body language. The project manager then began to provide feedback on what was said using phrases like “What I hear you say is…” or “It sounds like.…” The project manager was clarifying the message that was communicated by the client.

The project manager then asked more probing questions and reflected on what was said. “It sounds as if it was a very tough board meeting.” “Is there something going on beyond the events of the project?” From these observations and questions, the project manager discovered that the SMT meeting did not go well. The agency had experienced challenges and may require to cuts back the human resources committed for project and an expectation that the project would finish earlier than planned. The project manager also discovered that the client’s relationship with the agency would depend on the success of the project. The project manager asked, “Do you think we will need to do things differently?” They began to develop a plan to address the SMT’ concerns.

Through active listening, the project manager was able to develop an understanding of the issues that emerged from the SMT meeting and participate in developing solutions. Active listening and the trusting environment established by the project manager enabled the client to safely share information he had not planned on sharing and to participate in creating a workable plan that resulted in a successful project.

In the example above, the project manager used the following techniques:

- Listening intently to the words of the client and observing the client’s body language

- Nodding and expressing interest in the client without forming rebuttals

- Providing feedback and asking for clarity while repeating a summary of the information back to the client

- Expressing understanding and empathy for the client

Active listening was important in establishing a common understanding from which an effective project plan could be developed.

Negotiation

When multiple people are involved in an endeavor, differences in opinions and desired outcomes naturally occur. Negotiation is a process for developing a mutually acceptable outcome when the desired outcome for each party conflicts. A project manager will often negotiate with a client, team members, vendors, and other project stakeholders. Negotiation is an important skill in developing support for the project and preventing frustration among all parties involved, which could delay or cause project failure.

Negotiations involve four principles:

- Separate people from the problem. Framing the discussions in terms of desired outcomes enables the negotiations to focus on finding new outcomes.

- Focus on common interests. By avoiding the focus on differences, both parties are more open to finding solutions that are acceptable.

- Generate options that advance shared interests. Once the common interests are understood, solutions that do not match with either party’s interests can be discarded, and solutions that may serve both parties’ interests can be more deeply explored.

- Develop results based on standard criteria. The standard criterion is the success of the project. This implies that the parties develop a common definition of project success.

For the project manager to successfully negotiate issues on the project, he or she should first seek to understand the position of the other party. If negotiating with a client, what is the concern or desired outcome of the client? What are the business drivers and personal drivers that are important to the client? Without this understanding, it is difficult to find a solution that will satisfy the client. The project manager should also seek to understand what outcomes are desirable to the project. Typically, more than one outcome is acceptable. Without knowing what outcomes are acceptable, it is difficult to find a solution that will produce that outcome.

One of the most common issues in formal negotiations is finding a mutually acceptable price for a service or product. Understanding the market value for a product or service will provide a range for developing a negotiating strategy. The price paid on the last project or similar projects provides information on the market value. Seeking expert opinions from sources who would know the market is another source of information. Based on this information, the project manager can then develop an expected range within the current market from the lowest price to the highest price.

Additional factors will also affect the negotiated price. The project manager may be willing to pay a higher price to assure an expedited delivery or a lower price if delivery can be made at the convenience of the supplier or if payment is made before the product is delivered. Developing as many options as possible provides a broader range of choices and increases the possibility of developing a mutually beneficial outcome.

The goal of negotiations is not to achieve the lowest costs, although that is a major consideration, but to achieve the greatest value for the project. If the supplier believes that the negotiations process is fair and the price is fair, the project is more likely to receive higher value from the supplier. The relationship with the supplier can be greatly influenced by the negotiation process and a project manager who attempts to drive the price unreasonably low or below the market value will create an element of distrust in the relationship that may have negative consequences for the project. A positive negotiation experience may create a positive relationship that may be beneficial, especially if the project begins to fall behind schedule and the supplier is in a position to help keep the project on schedule.

Conflict Resolution

Conflict on a project is to be expected because of the level of stress, lack of information during early phases of the project, personal differences, role conflicts, and limited resources. Although good planning, communication, and team building can reduce the amount of conflict, conflict will still emerge. How the project manager deals with the conflict results in the conflict being destructive or an opportunity to build energy, creativity, and innovation.

David Whetton and Kim Cameron developed a response-to-conflict model that reflected the importance of the issue balanced against the importance of the relationship[6]. The model presented five responses to conflict:

- Avoiding

- Forcing

- Collaborating

- Compromising

- Accommodating

Each of these approaches can be effective and useful depending on the situation. Project managers will use each of these conflict resolution approaches depending on the project manager’s personal approach and an assessment of the situation.

Most project managers have a default approach that has emerged over time and is comfortable. For example, some project managers find the use of the project manager’s power the easiest and quickest way to resolve problems. “Do it because I said to” is the mantra for project managers who use forcing as the default approach to resolve conflict. Some project managers find accommodating with the client the most effective approach to dealing with client conflict.

The effectiveness of a conflict resolution approach will depend on the situation. The forcing approach often succeeds in a situation where a quick resolution is needed, and the investment in the decision by the parties involved is low.

Example: Resolving an Office Space Conflict

Two senior managers both want the office with the window. The project manager intercedes with little discussion and assigns the window office to the manager with the most seniority. The situation was a low-level conflict with no long-range consequences for the project and a solution all parties could accept.

Sometimes office size and location is culturally important, and this situation would take more investment to resolve.

Example: Conflict over a Change Order

In another example, the client rejected a request for a change order because she thought the change should have been foreseen by the project team and incorporated into the original scope of work. The project controls manager believed the client was using her power to avoid an expensive change order and suggested the project team refuse to do the work without a change order from the client.

This is a more complex situation, with personal commitments to each side of the conflict and consequences for the project. The project manager needs a conflict resolution approach that increases the likelihood of a mutually acceptable solution for the project. One conflict resolution approach involves evaluating the situation, developing a common understanding of the problem, developing alternative solutions, and mutually selecting a solution. Evaluating the situation typically includes gathering data. In our example of a change order conflict, gathering data would include a review of the original scope of work and possibly of people’s understandings, which might go beyond the written scope. The second step in developing a resolution to the conflict is to restate, paraphrase, and reframe the problem behind the conflict to develop a common understanding of the problem. In our example, the common understanding may explore the change management process and determine that the current change management process may not achieve the client’s goal of minimizing project changes. This phase is often the most difficult and may take an investment of time and energy to develop a common understanding of the problem.

After the problem has been restated and agreed on, alternative approaches are developed. This is a creative process that often means developing a new approach or changing the project plan. The result is a resolution to the conflict that is mutually agreeable to all team members. If all team members believe every effort was made to find a solution that achieved the project charter and met as many of the team member’s goals as possible, there will be a greater commitment to the agreed-on solution.

Delegation

Delegating responsibility and work to others is a critical project management skill. The responsibility for executing the project belongs to the project manager. Often other team members on the project will have a functional responsibility on the project and report to a functional manager in the parent organization. For example, the procurement leader for a major project may also report to the organization’s vice-president for procurement. Although the procurement plan for the project must meet the organization’s procurement policies, the procurement leader on the project will take day-to-day direction from the project manager. The amount of direction given to the procurement leader, or others on the project, is the decision of the project manager.

If the project manager delegates too little authority to others to make decisions and take action, the lack of a timely decision or lack of action will cause delays on the project. Delegating too much authority to others who do not have the knowledge, skills, or information will typically cause problems that result in delay or increased cost to the project. Finding the right balance of delegation is a critical project management skill.

When developing the project team, the project manager selects team members with the knowledge, skills, and abilities to accomplish the work required for the project to be successful. Typically, the more knowledge, skills, abilities, and experience a project team member brings to the project, the more that team member will be paid. To keep the project personnel costs lower, the project manager will develop a project team with the level of experience and the knowledge, skills, and abilities to accomplish the work.

On smaller, less complex projects, the project manager can provide daily guidance to project team members and be consulted on all major decisions. On larger, more complex projects, there are too many important decisions made every day for the project manager to be involved at the same level, and project team leaders are delegated decision-making authority. Larger projects, with a more complex profile will typically pay more because of the need for the knowledge and experience. On larger, more complex projects, the project manager will develop a more experienced and knowledgeable team that will enable the project manager to delegate more responsibility to these team members.

Example: Learning Project in Abu Dhabi

The project to purchase helicopters for the Abu Dhabi Police Force was falling behind schedule, and a new manager was assigned to the design team, which was the one most behind schedule. He was an experienced project manager from Canada with a reputation for meeting aggressive schedules. However, he failed to see that as a culture, Arabians do a great deal more socializing than teams in Canada. The project manager’s communication with the team was then limited because he did not go out and spend time with them, and his team did not develop trust or respect for him. Due to these cultural differences, the project fell further behind, and another personnel change had to be made at a significant cost of time, trust, and money.

The project manager must have the skills to evaluate the knowledge, skills, and abilities of project team members and evaluate the complexity and difficulty of the project assignment. Often project managers want project team members they have worked with in the past. Because the project manager knows the skill level of the team member, project assignments can be made quickly with less supervision than with a new team member with whom the project manager has little or no experience.

Delegation is the art of creating a project organizational structure with the work organized into units that can be managed. Delegation is the process of understanding the knowledge, skills, and abilities needed to manage that work and then matching the team members with the right skills to do that work. Good project managers are good delegators.

Team Development and Behaviour

A team is a collaboration of people with different personalities that is led by a person with a favored leadership style. Tuckman’s model of team development – Forming, Storming, Norming, Performing and Adjourning is a helpful explanation of team development behaviour. The model explains that as the team develops maturity and ability, relationships establish, and the leader changes leadership style. Beginning with a direct style, the leader moves through coaching, then participating, finishing with delegating

Managing the interactions of the various personalities and styles as a group is an important aspect of project management.

Trust

Trust is the foundation for all relationships within a project. Without a minimum level of trust, communication breaks down, and eventually the project suffers in the form of costs increasing and schedules slipping. Often, when reviewing a project where the performance problems have captured the attention of upper management, the evidence of problems is the increase in project costs and the slippage in the project schedule. The underlying cause is usually blamed on communication breakdown. With deeper investigation, the communication breakdown is associated with a breakdown in trust.

On projects, trust is the filter through which we screen information that is shared and the filter we use to screen information we receive. The more trust that exists, the easier it is for information to flow through the filters. As trust diminishes, the filters become stronger and information has a harder time getting through, and projects that are highly dependent on an information-rich environment will suffer from information deprivation.

Contracts and Trust Relationships

A project typically begins with a charter or contract. A contract is a legal agreement that includes penalties for any behaviour or results not achieved. Contracts are based on an adversarial paradigm and do not lend themselves to creating an environment of trust. Contracts and charters are necessary to clearly establish the scope of the project, among other things, but they are not conducive to establishing a trusting project culture.

A relationship of mutual trust is less formal but vitally important. When a person or team enters into a relationship of mutual trust, each person’s reputation and self-respect are the drivers in meeting the intent of the relationship. A relationship of mutual trust within the context of a project is a commitment to an open and honest relationship. There is nothing that enforces the commitments in the relationship except the integrity of the people involved. Smaller, less complex projects can operate within the boundaries of a legal contract, but larger, more complex projects must develop a relationship of mutual trust to be successful.

Types of Trust

Svenn Lindskold describes four kinds of trust[7]:

- Objective credibility. A personal characteristic that reflects the truthfulness of an individual that can be checked against observable facts.

- Attribution of benevolence. A form of trust that is built on the examination of the person’s motives and the conclusion that they are not hostile.

- Non-manipulative trust. A form of trust that correlates to a person’s self-interest and the predictability of a person’s behaviour in acting consistent in that self-interest.

- High cost of lying. The type of trust that emerges when persons in authority raise the cost of lying so high that people will not lie because the penalty will be too high.

Creating Trust

Building trust on a project begins with the project manager. On complex projects, the assignment of a project manager with a high trust reputation can help establish the trust level needed. The project manager can also establish the cost of lying in a way that communicates an expectation and a value for trust on the project. Project managers can also assure that the official goals (stated goals) and operational goals (goals that are reinforced) are aligned. The project manager can create an atmosphere where informal communication is expected and reinforced.

The informal communication is important to establishing personal trust among team members and with the client. Allotting time during project start-up meetings to allow team members to develop a personal relationship is important to establishing the team trust. The informal discussion allows for a deeper understanding of the whole person and creates an atmosphere where trust can emerge.

Example: High Cost of Lying in a Project

On the project in Abu Dhabi, the client was asking for more and more backup to information from the project. The project manager visited the client to better understand the reporting requirements and discovered the client did not trust the reports coming from the project and wanted validating material for each report. After some candid discussion, the project manager discovered that one of the project team members had provided information to the client that was inaccurate. The team member had made a mistake but had not corrected it with the client, hoping that the information would get lost in the stream of information from the project. The project manager removed the team member from the project for two main reasons. The project manager established that the cost of lying was high. The removal communicated to the project team an expectation of honesty. The project manager also reinforced a covenant with the client that reinforced the trust in the information the project provided. The requests for additional information declined, and the trust relationship between project personnel and the client remained high.

Small events that reduce trust often take place on a project without anyone remembering what happened to create the environment of distrust. Taking fast and decisive action to establish a high cost of lying, communicating the expectation of honesty, and creating an atmosphere of trust are critical steps a project manager can take to ensure the success of complex projects.

Project managers can also establish expectations of team members to respect individual differences and skills, look and react to the positives, recognize each other’s accomplishments, and value people’s self-esteem to increase a sense of the benevolent intent.

Types of Meetings

Skilled project managers know what type of meeting is needed and how to develop an atmosphere to support the meeting type. Meetings of the action item type are focused on information sharing with little discussion. They require efficient communication of plans, progress, and other information team members need to plan and execute daily work. Management type meetings are focused on developing and progressing goals. Leadership meetings are more reflective and focused on the project mission and culture.

These three types of meetings do not cover all the types of project meetings. Specific problem-solving, vendor evaluation, and scheduling meetings are examples of typical project meetings. Understanding what kinds of meetings are needed on the project and creating the right focus for each meeting type is a critical project management skill.

Types of Teams

Teams can outperform individual team members in several situations. The effort and time invested in developing a team and the work of the team are large investments of project resources, and the payback is critical to project success. Determining when a team is needed and then chartering and supporting the development and work of the team are other critical project management abilities.

Teams are effective in several project situations:

- When no one person has the knowledge, skills, and abilities to either understand or solve the problem

- When a commitment to the solution is needed by large portions of the project team

- When the problem and solution cross project functions

- When innovation is required

Individuals can outperform teams on some occasions. An individual tackling a problem consumes fewer resources than a team and can operate more efficiently—as long as the solution meets the project’s needs. A person is most appropriate in the following situations:

- When speed is important

- When one person has the knowledge, skills, and resources to solve the problem

- When the activities involved in solving the problem are very detailed

- When the actual document needs to be written (Teams can provide input, but writing is a solitary task.)

In addition to knowing when a team is appropriate, the project manager must also understand what type of team will function best.

Functional Teams

A functional team refers to the team approach related to the project functions. The engineering team, the procurement team, and the project controls team are examples of functional teams within the project. On a project with a low complexity profile that includes low technological challenges, good team member experience, and a clear scope of work, the project manager can utilize well-defined functional teams with clear expectations, direction, and strong vertical communication.

Cross-Functional Teams

Cross-functional teams address issues and work processes that include two or more of the functional teams. The team members are selected to bring their functional expertise to addressing project opportunities.

Problem-Solving Teams

Problem-solving teams are assigned to address specific issues that arise during the life of the project. The project leadership includes members that have the expertise to address the problem. The team is chartered to address that problem and then disband.

Qualitative Assessment of Project Performance

Project managers should provide an opportunity to ask such questions as “What is your gut feeling about how the project going?” and “How do you think our client perceives the project?” This creates the opportunity for reflection and dialogue around larger issues on the project. The project manager creates an atmosphere for the team to go beyond the data and search for meaning. This type of discussion and reflection is very difficult in the stress of day-to-day problem solving.

The project manager has several tools for developing good quantitative information—based on numbers and measurements—such as the project schedules, budgets and budget reports, risk analysis, and goal tracking. This quantitative information is essential to understanding the current status and trends on the project. Just as important is the development of qualitative information—comparisons of qualities—such as judgments made by expert team members that go beyond the quantitative data provided in a report. Some would label this the “gut feeling” or intuition of experienced project managers.

The Human Factor is a survey tool developed by Russ Darnall to capture the thoughts of project participants. It derived its name from a project manager who always claimed he could tell you more by listening to the hum of the project than reading all the project reports. “Do you feel the project is doing the things it needs to do to stay on schedule?” and “Is the project team focused on project goals?” are the types of questions that can be included in the Human Factor. It is distributed on a weekly or less frequent basis depending on the complexity profile of the project. A project with a high level of complexity due to team-based and cultural issues will be surveyed more frequently.

The qualitative responses are converted to a quantitative value as a score from 1 to 10. Responses are tracked by individuals and the total project, resulting in qualitative comparisons over time. The project team reviews the ratings regularly, looking for trends that indicate an issue may be emerging on the project that might need exploring.

Example: Humm Survey Uncovers Concerns

On the project in Abu Dhabi the project surveyed the project leadership with a Humm Survey each week. The Humm Factor indicated an increasing worry about the schedule beginning to slip when the schedule reports indicated that everything was according to plan. When the project manager began trying to understand why the Humm Factor was showing concerns about the schedule, he discovered an apprehension about the performance of a critical project supplier. When he asked team members, they responded, “It was the way they answered the phone or the hesitation when providing information—something didn’t feel right.”

The procurement manager visited the supplier and discovered the company was experiencing financial problems and had serious cash flow problems. The project manager was able to develop a plan to help the supplier through the period, and the supplier eventually recovered. The project was able to meet performance goals. The Humm Factor survey provided a tool for members of the project team to express concerns that were based on very soft data, and the project team was able to discover a potential problem.

Another project team used the Humm Factor to survey the client monthly. The completed surveys went to a person who was not on the project team to provide anonymity to the responses. The responses were discussed at the monthly project review meetings, and the project manager summarized the results and addressed all the concerns expressed in the report. “I don’t feel my concerns are being heard” was one response that began increasing during the project, and the project manager spent a significant portion of the next project review meeting attempting to understand what this meant. The team discovered that as the project progressed toward major milestones, the project team became more focused on solving daily problems, spent more time in meetings, and their workday was becoming longer. The result was fewer contacts with the clients, slower responses in returning phone calls, and much fewer coffee breaks where team members could casually discuss the project with the client.

The result of the conversation led to better understanding by both the project team and client team of the change in behaviour based on the current phase of the project and the commitment to developing more frequent informal discussion about the project.

Creating a Project Culture

Project managers have a unique opportunity during the start-up of a project. They create a project culture, something organizational managers seldom have a chance to do. In most organizations, the corporate or organizational culture has developed over the life of the organization, and people associated with the organization understand what is valued, what has status, and what behaviours are expected. Edgar Schein identified three distinct levels in organizational culture:

- Artifacts and behaviours

- Espoused values

- Assumptions

Artifacts are the visible elements in a culture and they can be recognized by people not part of the culture. Espoused values are the organization’s stated values and rules of behaviour. Shared basic assumptions are the deeply embedded, taken-for-granted behaviours that are usually unconscious, but constitute the essence of culture.

Characteristics of Project Culture

A project culture represents the shared norms, beliefs, values, and assumptions of the project team. Understanding the unique aspects of a project culture and developing an appropriate culture to match the complexity profile of the project are important project management abilities.

Culture is developed through the communication of:

- The priority

- The given status

- The alignment of official and operational rules

Official rules are the rules that are stated, and operational rules are the rules that are enforced. Project managers who align official and operational rules are more effective in developing a clear and strong project culture because the project rules are among the first aspects of the project culture to which team members are exposed when assigned to the project.

Example: Creating a Culture of Collaboration

A project manager met with his team prior to the beginning of an instructional design project. The team was excited about the prestigious project and the potential for career advancement involved. With this increased competitive aspect came the danger of selfishness and backstabbing. The project leadership team told stories of previous projects where people were fired for breaking down the team efforts and often shared inspirational examples of how teamwork created unprecedented successes—an example of storytelling. Every project meeting started with teambuilding exercises—a ritual—and any display of hostility or separatism was forbidden—taboo—and was quickly and strongly cut off by the project leadership if it occurred.

Culture guides behaviour and communicates what is important and is useful for establishing priorities. On projects that have a strong culture of trust, team members feel free to challenge anyone who breaks a confidence, even managers. The culture of integrity is stronger than the cultural aspects of the power of management.

Innovation on Projects

The requirement of innovation on projects is influenced by the nature of the project. Some projects are chartered to develop a solution to a problem, and innovation is a central ingredient of project success. The lack of availability of education to the world at large prompted the open education movement, a highly innovative endeavor, which resulted in the textbook you are now reading. Innovation is also important to developing methods of lowering costs or shortening the schedule. Traditional project management thinking provides a trade-off between cost, quality, and schedule. A project sponsor can typically shorten the project schedule with an investment of more money or a lowering of quality. Finding innovative solutions can sometimes lower costs while also saving time and maintaining the quality.

Innovation is a creative process that requires both fun and focus. Stress is a biological reaction to perceived threats. Stress, at appropriate levels, can make the work environment interesting and even challenging. Many people working on projects enjoy a high-stress, exciting environment. When the stress level is too high, the biological reaction increases blood flow to the emotional parts of the brain and decreases the blood flow to the creative parts of the brain, making creative problem solving more difficult. Fun reduces the amount of stress on the project. Project managers recognize the benefits of balancing the stress level on the project with the need to create an atmosphere that enables creative thought.

Example: Stress Managed on a Website Design Project

When a project manager visited the team tasked with designing the website for a project, she found that most of the members were feeling a great deal of stress. As she probed to find the reason behind the stress, she found that in addition to designing, the team was increasingly facing the need to build the website as well. As few of them had the necessary skills, they were wasting time that could be spent designing trying to learn building skills. Once the project manager was able to identify the stress as well as its cause, she was able to provide the team with the support it needed to be successful.

Exploring opportunities to create savings takes an investment of time and energy, and on a time-sensitive project, the project manager must create the motivation and the opportunity for creative thinking.

Key Takeaways

- A project is successful when it achieves its objectives and meets or exceeds the expectations of the stakeholders

- It’s important to identify all the stakeholders in your project upfront. Leaving out important stakeholders or their department’s function and not discovering the error until well into the project could be a project killer

- The project team is made up of those people dedicated to the project. The team can include contracted or borrowed team members who work full-time or on a part-time basis.

- As project manager, you need management skills, such as planning, organizing, leading and controlling (POLC) to provide leadership, direction, and above all, support your team members as they go about accomplishing their tasks.

- Managing project team members requires interpersonal skills.

- Working with other people involves dealing with them both logically and emotionally.

- A successful working relationship between individuals begins with appreciating the importance of emotions and how they relate to personality types, leadership styles, negotiations, and setting goals.

- Understanding your personality type as a project manager will assist you in evaluating your tendencies and strengths in different situations. Understanding others’ personality types can also help you coordinate the skills of your individual team members and address the various needs of your client.

- Leadership style is a function of both the personal characteristics and life experiences of the leader and the environment in which the leadership must occur.

- No particular leadership approach is specifically appropriate for managing a project. Due to the unique circumstances inherent in each project, the leadership approach and the management skills required to be successful vary depending on the complexity profile of the project.

- The successful project manager must have good communication skills and other skills. These skills include administrative skills, organizational skills, and technical skills associated with the technology of the project. The types of skills and the depth of the skills needed are closely connected to the complexity profile of the project.

- The project manager must have the skills to evaluate the knowledge, skills, and abilities of project team members and evaluate the complexity and difficulty of the project assignment.

- The project manager has several tools for developing good quantitative information—based on numbers and measurements—such as the project schedules, budget reports, risk analysis, and goal tracking. This quantitative information is essential to understanding the current status and trends on the project. Equally important is the development of qualitative information—such as judgments made by expert team members which goes beyond the quantitative data provided in a report.

- A project culture represents the shared norms, beliefs, values, and assumptions of the project team. Understanding the unique aspects of a project culture and developing an appropriate culture to match the complexity profile of the project are important project management abilities.

Attribution

This chapter is based on chapter 5 Stakeholder Management and 11 Resource Planning in Project Management by Adrienne Watt. Watt’s Chapter 5 & 11 CC BY 4.0 are adapted from the following texts:

- Project Management by Merrie Barron and Andrew Barron. © CC BY (Attribution).

- Project Decelerators – Lack of Stakeholder Support by Jose Solera. © CC BY (Attribution).

- How to Build Relationships with Stakeholders by Erin Palmer. © CC BY (Attribution).

- Project Management From Simple to Complex by Russel Darnall, John Preston, Eastern Michigan University. © CC BY (Attribution).

- Resource Management, Edgar Schein, and Resource Leveling by Wikipedia. © CC BY-SA (Attribution-ShareAlike).

- Project Management for Instructional Designers by Amado, M., et. al. © Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Licence.

- Tannenbaum, R., & Schmidt, W. (1958). How to Choose a Leadership Pattern. Harvard Business Review 36, 95–101. ↵

- Leavitt, H. (1986). Corporate Pathfinders. New York: Dow-Jones-Irwin and Penguin Books. ↵

- Burns, J.M. (1978). Leadership. New York: Harper & Row. ↵

- Fiedler, F.E. (1971). Validation and Extension of the Contingency Model of Leadership Effectiveness. Psychological Bulletin, 76(2), 128–48. ↵

- Shi, Q., & Chen, J. (2006). The Human Side of Project Management: Leadership Skills. Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute. ↵

- Whetton, D., & Cameron, K. (2005). Developing Management Skills. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education. ↵

- Lindskold, S. (1978). Trust Development, the GRIT Proposal, and the Effects of Conciliatory Acts on Conflict and Corporation. Psychological Bulletin 85(4), 772–93. ↵