6. Defining Scope & Quality

Learning Objectives

- Define project scope.

- Prepare a scope document.

- Develop a Work Breakdown Structure (WBS).

- Examine the significance of WBS

- Explain quality management and its significance in relation to customer satisfaction

- Examine how integral quality is to all aspects of project management.

- Identify tools for quality planning and management.

You always want to know exactly what work has to be done before you start it. You have a collection of team members, and you need to know exactly what they’re going to do to meet the project’s objectives. The scope planning process is the very first thing you do to manage your scope. When you start the project, you need to have a clear picture of all the work that needs to happen on your project, and as the project progresses, you need to keep that scope up to date and written down in the project’s scope management plan.

Defining the Scope

Once you have determined the objective of the project, you need to plan further and write down all the intermediate and final deliverables that you and your team will produce over the course of the project. Deliverables include everything that you and your team produce for the project. The deliverables for your project include all of the products or services that you and your team are performing for the client, customer, or sponsor. They include every intermediate document, plan, schedule, budget, blueprint, and anything else that will be made along the way, including all of the project management documents you put together. Project deliverables are tangible outcomes, measurable results, or specific items that must be produced to consider either the project or the project phase completed.

All deliverables must be described in a sufficient level of detail so that they can be differentiated. For example:

- A twin engine plane versus a single engine plane

- A red marker versus a green marker

- A daily report versus a weekly report

One of the project manager’s primary functions is to accurately document the deliverables of the project and then manage the project so that they are produced according to the agreed-on criteria. Deliverables are the output of each development phase, described in a quantifiable way.

Project Requirements

After all the deliverables are identified, the project manager needs to document all the requirements of the project. Requirements describe the characteristics of the final deliverable, whether it is a product or a service. A requirement is an objective that must be met. The project’s requirements, defined in the scope plan, describe what a project is supposed to accomplish and how the project is supposed to be created and implemented. Requirements answer the following questions regarding states of the business: who, what, where, when, how much, and how does a business process work?

Requirements may include attributes like dimensions, ease of use, color, specific ingredients, and so on. Requirements must be measurable, testable, related to identified business needs or opportunities, and defined to a level of detail sufficient for system design. They can be divided into six basic categories: functional, non-functional, technical, business, user, and regulatory requirements.

Measuring Requirements

As a practical matter, it is typically useful to have some concept of the volume of the requirements for a particular software product. This number is useful in evaluating the size of a change in requirements, in estimating the cost of a development or maintenance task, or simply in using it as the denominator in other measurements (see Table 6.1)

[table id=1 /]

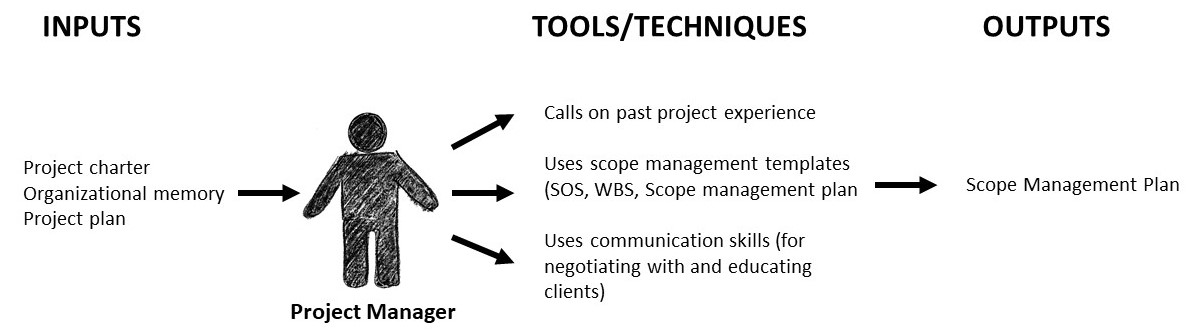

Scope Inputs

The project manager gathers initial project facts from the project charter. In addition, background information on the stakeholder’s workplace, existing business model and rules, etc. assist in creating the vision of the final product/service, and consequently, the project scope.

Techniques

An experienced project manager can draw on past experiences with like projects to determine the work that is realistically doable, given time and cost constraints, for a current project. Communication and negotiation skills are a “must-have” as well. Project managers need to educate stakeholders about the project impacts of some requirements. Adding complexity to a project may require more staff, time, and/or money. It may also have an impact on project quality. Some aspects of the project may be unfeasible – stakeholders need to know this so they can adjust their vision or prepare for future challenges. Gathering requirements is part of scope definition, and it can be done using one or more of following techniques:

Work Breakdown Structure

Now that we have the deliverables and requirements well defined, the process of breaking down the work of the project via a work breakdown structure (WBS) begins. The WBS defines the scope of the project and breaks the work down into components that can be scheduled, estimated, and easily monitored and controlled. The idea behind the WBS is simple: you subdivide a complicated task into smaller tasks, until you reach a level that cannot be further subdivided. Anyone familiar with the arrangements of folders and files in a computer memory or who has researched their ancestral family tree should be familiar with this idea. You stop breaking down the work when you reach a low enough level to perform an estimate of the desired accuracy. At that point, it is usually easier to estimate how long the small task will take and how much it will cost to perform than it would have been to estimate these factors at the higher levels. Each descending level of the WBS represents an increased level of detailed definition of the project work.

WBS describes the products or services to be delivered by the project and how they are decomposed and related. It is a delive of a project into smaller components. It defines and groups a project’s discrete work elements in a way that helps organize and define the total work scope of the project.

A WBS also provides the necessary framework for detailed cost estimating and control, along with providing guidance for schedule development and control.

Overview

WBS is a hierarchical decomposition of the project into phases, deliverables, and work packages. It is a tree structure, which shows a subdivision of effort required to achieve an objective (e.g., a program, project, and contract). In a project or contract, the WBS is developed by starting with the end objective and successively subdividing it into manageable components in terms of size, duration, and responsibility (e.g., systems, subsystems, components, tasks, subtasks, and work packages), which include all steps necessary to achieve the objective.

The WBS creation involves:

- Listing all the project outputs (deliverables and other direct results)

- Identifying all the activities required to deliver the outputs

- Subdividing these activities into sub-activities and tasks

- Identifying the deliverable and milestone(s) of each task

- Identifying the time usage of all the resources (personnel and material) required to complete each task

The purpose of developing a WBS is to:

- Allow easier management of each component

- Allow accurate estimation of time, cost, and resource requirements

- Allow easier assignment of human resources

- Allow easier assignment of responsibility for activities.

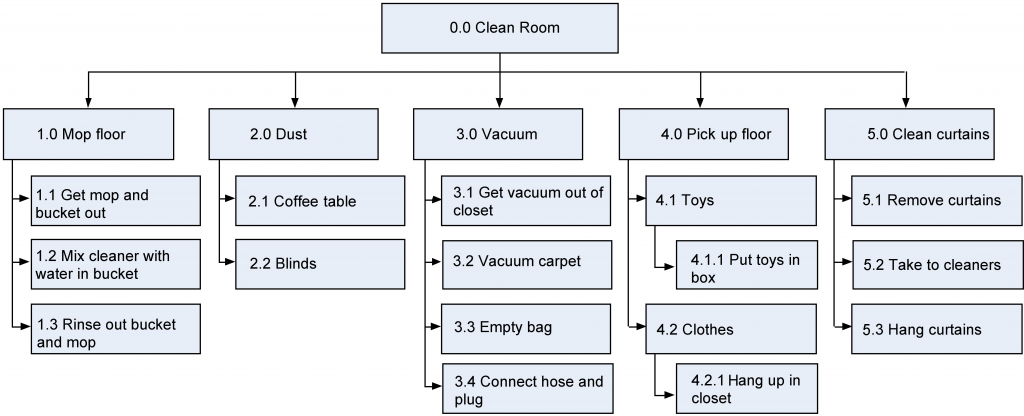

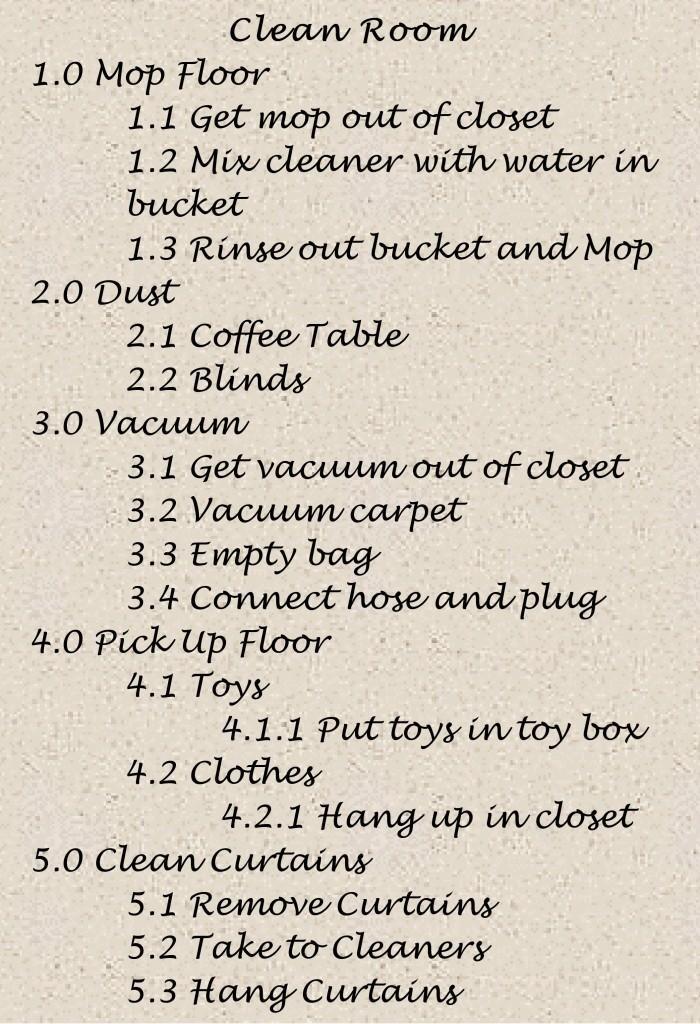

Example of a WBS

If I want to clean a room, I might begin by picking up clothes, toys, and other things that have been dropped on the floor. I could use a vacuum cleaner to get dirt out of the carpet. I might take down the curtains and take them to the cleaners, and then dust the furniture. All of these tasks are sub-tasks performed to clean the room. As for vacuuming the room, I might have to get the vacuum cleaner out of the closet, connect the hose, empty the bag, and put the machine back in the closet. These are smaller tasks to be performed in accomplishing the sub-task called vacuuming.

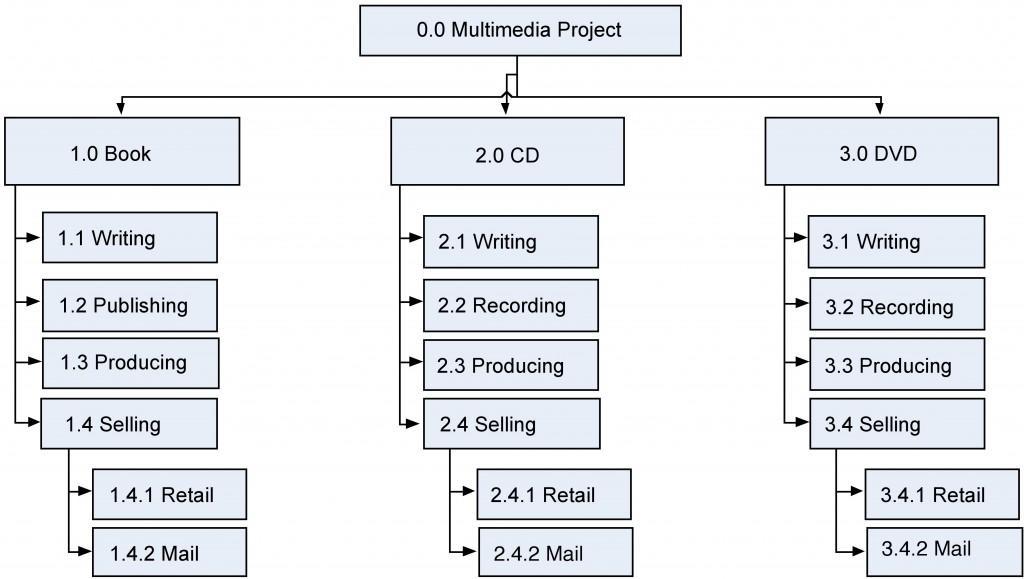

It is very important to note that we do not worry about the sequence in which the work is performed or any dependencies between the tasks when we do a WBS. That will be worked out when we develop the schedule. For example, under 3.0 Vacuum, it would be obvious that 3.3 Vacuum carpet would be performed after 3.4 Connect hose and plug! However, you will probably find yourself thinking sequentially, as it seems to be human nature to do so. The main idea of creating a WBS is to capture all of the tasks, irrespective of their order. So if you find yourself and other members of your team thinking sequentially, don’t be too concerned, but don’t get hung up on trying to diagram the sequence or you will slow down the process of task identification. A WBS can be structured any way it makes sense to you and your project. In practice, the chart structure is used quite often but it can be composed in outline form as well.

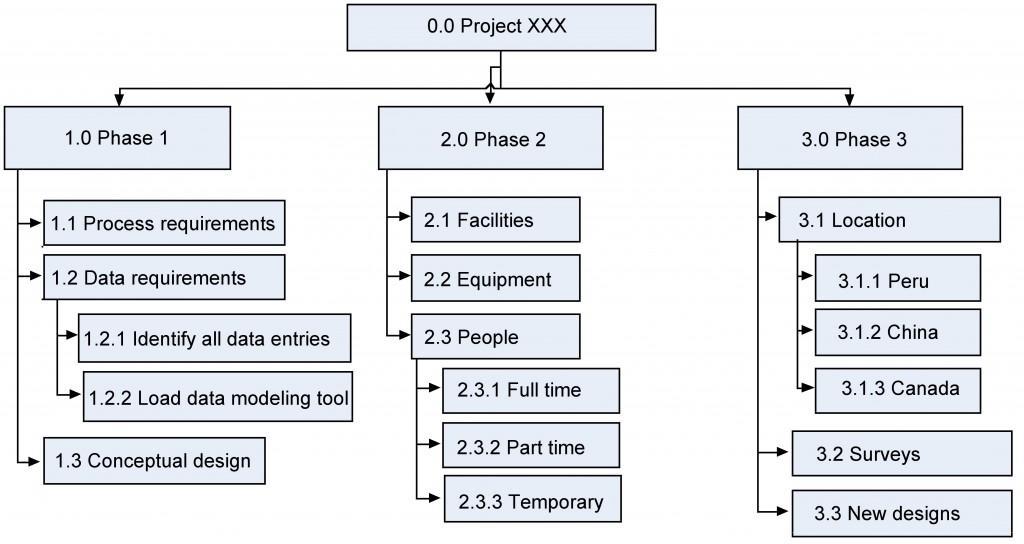

You’ll notice that each element at each level of the WBS in both figures is assigned a unique identifier. This unique identifier is typically a number, and it’s used to sum and track costs, schedules, and resources associated with WBS elements.

There are also many ways you can organize the WBS. For example, it can be organized by either deliverable or phase. The major deliverables of the project are used as the first level in the WBS. For example, if you are doing a multimedia project the deliverables might include producing a book, CD, and a DVD (Figure 6.4).

Many projects are structured or organized by project phases (Figure 9.6). Each phase would represent the first level of the WBS and their deliverables would be the next level and so on.

The project manager is free to determine the number of levels in the WBS based on the complexity of the project. You need to include enough levels to accurately estimate project time and costs but not so many levels that are difficult to distinguish between components. Regardless of the number of levels in a WBS, the lowest level is called a work package.

Work packages are the components that can be easily assigned to one person or a team of people, with clear accountability and responsibility for completing the assignment. The work-package level is where time estimates, cost estimates, and resource estimates are determined.

100 Percent Rule

The 100 percent rule is the most important criterion in developing and evaluating the WBS. The rule states that each decomposed level (child) must represent 100 percent of the work applicable to the next higher (parent) element. In other words, if each level of the WBS follows the 100 percent rule down to the activities, then we are confident that 100 percent of the activities will have been identified when we develop the project schedule. When we create the budget for our project, 100 percent of the costs or resources required will be identified.

Scope Statement

Scope statements may take many forms depending on the type of project being implemented and the nature of the organization. The scope statement details the project deliverables and describes the major objectives. The objectives should include measurable success criteria for the project.

A scope statement captures, in very broad terms, the product of the project: for example, “development of a software-based system to capture and track orders for software.” A scope statement should also include the list of users using the product, as well as the features in the resulting product.

As a baseline scope statements should contain:

- The project name

- The project charter

- The project owner, sponsors, and stakeholders

- The problem statement

- The project goals and objectives

- The project requirements

- The project deliverables

- The project non-goals (what is out of scope)

- Milestones

- Cost estimates

In more project-oriented organizations, the scope statement may also contain these and other sections:

- Project scope management plan

- Approved change requests

- Project assumptions and risks

- Project acceptance criteria

Quality Management

It’s not enough to make sure you get a project done on time and under budget. You need to be sure you make the right product to suit your stakeholders’ needs. Quality means making sure that you build what you said you would and that you do it as efficiently as you can.

Everybody “knows” what quality is. But the way the word is used in everyday life is a little different from how it is used in project management. Just like the triple constraint (scope, cost, and schedule), you manage quality on a project by setting goals and taking measurements. That’s why you must understand the quality levels your stakeholders believe are acceptable, and ensure that your project meets those targets, just like it needs to meet their budget and schedule goals.

Customer satisfaction is about making sure that the people who are paying for the end product are happy with what they get. When the team gathers requirements for the specification, they try to write down all of the things that the customers want in the product so that you know how to make them happy. Some requirements can be left unstated. Those are the ones that are implied by the customer’s explicit needs. For example, some requirements are just common sense (e.g., a product that people hold can’t be made from toxic chemicals that may kill them). It might not be stated, but it’s definitely a requirement.

“Fitness to use” is about making sure that the product you build has the best design possible to fit the customer’s needs. Which would you choose: a product that’s beautifully designed, well-constructed, solidly built, and all around pleasant to look at but does not do what you need, or a product that does what you want despite being ugly and hard to use? You’ll always choose the product that fits your needs, even if it’s seriously limited. That’s why it’s important that the product both does what it is supposed to do and does it well. For example, you could pound in a nail with a screwdriver, but a hammer is a better fit for the job.

Conformance to requirements is the core of both customer satisfaction and fitness to use, and is a measure of how well your product does what you intend. Above all, your product needs to do what you wrote down in your requirements document. Your requirements should take into account what will satisfy your customer and the best design possible for the job. That means conforming to both stated and implied requirements.

In the end, your product’s quality is judged by whether you built what you said you would build.

Quality planning focuses on taking all of the information available to you at the beginning of the project and figuring out how you will measure quality and prevent defects. Your company should have a quality policy that states how it measures quality across the organization. You should make sure your project follows the company policy and any government rules or regulations on how to plan quality for your project.

You need to plan which activities you will use to measure the quality of the project’s product. And you’ll need to think about the cost of all the quality-related activities you want to do. Then you’ll need to set some guidelines for what you will measure against. Finally, you’ll need to design the tests you will run when the product is ready to be tested.

Quality planning tools

High quality is achieved by planning for it rather than by reacting to problems after they are identified. Standards are chosen and processes are put in place to achieve those standards. Planning for quality is part of the initial planning process. The early scope, budget, and schedule estimates are used to identify processes, services, or products where the expected grade and quality should be specified. Risk analysis is used to determine which of the risks to the project could affect quality.

Defining and Meeting Client Expectations

Clients provide specifications for the project that must be met for the project to be successful. Recall that meeting project specifications is one definition of project success. Clients often have expectations that are more difficult to capture in a written specification. For example, one client will want to be invited to every meeting of the project and will then select the ones that seem most relevant. Another client will want to be invited only to project meetings that need client input. Inviting this client to every meeting will cause unnecessary frustration. Listening to the client and developing an understanding of the expectations that are not easily captured in specifications is important to meeting those expectations.

Project surveys can capture how the client perceives the project performance and provide the project team with data that are useful in meeting client expectations. If the results of the surveys indicate that the client is not pleased with some aspect of the project, the project team has the opportunity to explore the reasons for this perception with the client and develop recovery plans. The survey can also help define what is going well and what needs improvement.

Techniques

Several different tools and techniques are available for planning and controlling the quality of a project. The extent to which these tools are used is determined by the project complexity and the quality management program in use by the client.

The following list represents the quality planning tools available to the project manager:

Once you have your quality plan, you know your guidelines for managing quality on the project. Your strategies for monitoring project quality should be included in the plan, as well as the reasons for all the steps you are taking. It’s important that everyone on the team understand the rationale behind the metrics being used to judge success or failure of the project.

Quality Assurance

The purpose of quality assurance is to create confidence that the quality plan and controls are working properly. Time must be allocated to review the original quality plan and compare that plan to how quality is being ensured during the implementation of the project.

Process Analysis

The flowcharts of quality processes are compared to the processes followed during actual operations. If the plan was not followed, the process is analyzed and corrective action taken. The corrective action could be to educate the people involved on how to follow the quality plan, or it could be to revise the plan.

Because projects are temporary, there are fewer opportunities to learn and improve within a project, especially if it has a short duration. But even in short projects, the quality manager should have a way to learn from experience and change the process for the next project of a similar complexity profile.

Example: Analyzing Quality Processes in Safety Training

The JIBC is responsible for training employees in safe plant practices evaluates its instructor selection process at the end of the training to see if it had the best criteria for selection. For example, it required the instructors to have master’s degrees in manufacturing to qualify as college instructors. The college used an exit survey of the students to ask what they thought would improve the instruction of future classes on this topic. Some students felt that it would be more important to require that the instructors have more years of training experience, while others recommended that instructors seek certification at a Work Safe BC training center. The institute considered these suggestions and decided to retain its requirement of a master’s degree but add a requirement that instructors be certified in plant safety.

Key Takeaways

- Project scope planning is concerned with the definition of all the work needed to successfully meet the project objectives.

- Requirements describe the characteristics of the final deliverable, whether it is a product or a service.

- Project deliverables are tangible outcomes, measurable results, or specific items that must be produced to consider either the project or the project phase completed.

- Work breakdown structure (WBS) is a technique used to decompose high-level project goals into the many tasks required to achieve them.

- WBS is a hierarchical decomposition of the project into phases, deliverables, and work packages. It is a tree structure, which shows a subdivision of effort required to achieve an objective.

- Once WBS is complete, managers can estimate the time and cost required to complete each task. They can also assign people to the tasks they’ve identified.

- The benefits of developing a WBS includes: defining task, identifying responsibility, aids project communication and provides an excellent graphical way to present the progress of the project.

- The WBS may reveal some challenging conclusions: The project will cost more than it’s worth, the organization lacks the skills to do the job, or the project will take too long to complete.

- A scope statement captures, in very broad terms, the product or service of the project. A scope statement specify what is within the scope of the project and what is not. It should also include the list of users using the product or service as well as the features in the resulting product. This is important to avoid scope creep.

- Managing project quality enables you to go from identifying customer needs to achieving customer satisfaction

- Effective quality management is consistent with effective project management.

Attribution

This chapter is based on chapter 9 and chapter 14 in Project Management by Adrienne Watt.

Chapter 9 in Project Management by Adrienne Watt CC BY 4.0 is a derivative the following texts:

- Project Management by Merrie Barron and Andrew Barron. CC BY (Attribution).

- Project Management/PMBOK/Scope Management and Development Cooperation Handbook/Designing and Executing Projects/Detailed Planning or design stage by Wikibooks. © CC BY-SA (Attribution-ShareAlike).

- Requirements Traceability Matrix by DHWiki. © CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives)

- Work Breakdown Structure by Wikipedia. © CC BY-SA (Attribution-ShareAlike).

- 100 Percent Rule by Pabipedia. © CC BY-SA (Attribution-ShareAlike).

Chapter 14 in Project Management by Adrienne Watt CC BY 4.0 is a derivative of Project Management for Instructional Designers by Wiley, et al. © CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike)