Chapter 11: The Enlightenment

In 1784, a Prussian philosopher named Immanuel Kant published a short essay entitled What is Enlightenment? He was responding to nearly a century of philosophical, scientific, and technical advances in Central and Western Europe that, he felt, had culminated in his own lifetime in a more enlightened and just age. According to Kant, Enlightenment was all about the courage to think for one’s self, to question the accepted notions of any field of human knowledge rather than relying on a belief imposed by an outside authority. Likewise, he wrote, ideas were now exchanged between thinkers in a network of learning that itself provided a kind of intellectual momentum. Kant’s point was that, more than ever before, thinkers of various kinds were breaking new ground not only in using the scientific method to discover new things about the physical world, but in applying rational inquiry toward improving human life and the organization of human society. While Kant’s essay probably overstated the Utopian qualities of the thought of his era, he was right that it did correspond to a major shift in how educated Europeans thought about the world and the human place in it.

Following Kant, historians refer to the intellectual movement of the eighteenth century as the Enlightenment. Historians now tend to reject the idea that the Enlightenment was a single, self-conscious movement of thinkers, but they still (usually) accept that there were indeed innovative new themes of thought running through much of the philosophical, literary, and technical writing of the period. Likewise, new forms of media and new forums of discussion came of age in the eighteenth century, creating a larger and better-informed public than ever before in European history.

The Enlightenment: Definitions

The Enlightenment was a philosophical movement that lasted about one hundred years, neatly corresponding to most of the eighteenth century; convenient dates for it are from the Glorious Revolution in Britain to the beginning of the French Revolution: 1688 – 1789. The central concern of the Enlightenment was applying rational thought to almost every aspect of human existence: not just science, but philosophy, morality, and society. Along with those philosophical themes, central to the Enlightenment was the emergence of new forms of media and new ways in which people exchanged information, along with new “sensibilities” regarding what was proper and desirable in social conduct and politics.

We owe the Enlightenment fundamental modern beliefs. Enlightenment thinkers embraced the idea that scientific progress was limitless. They argued that all citizens should be equal before the law. They claimed that the best forms of government were those with rational laws oriented to serve the public interest. In a major break from the past, they increasingly claimed that there was a real, physical universe that could be understood using the methods of science, in contrast to the false, made-up universe of “magic” suitable only for myths and storytelling. In short, Enlightenment thinkers proposed ideas that were novel at the time, but were eventually accepted by almost everyone in Europe (and many other places, not least the inhabitants of the colonies of the Americas).

The Enlightenment also introduced themes of thought that undermined traditional religious beliefs, at least in the long run. Perhaps the major theme of Enlightenment thought that ran contrary to almost every form of religious practice at the time was the rejection of “superstitions,” things that simply could not happen according to science (such a virgin giving birth to a child, or wine turning into blood during Communion). Most Enlightenment thinkers argued that the “real” natural universe was governed by natural laws, all watched over by a benevolent but completely remote “supreme being” – this was essentially the same as the Deism that had emerged from the Scientific Revolution. While few Enlightenment thinkers were outright atheists, almost all of them decried many church practices and what they perceived as the ignorance and injustice behind church (especially Catholic) laws.

The Enlightenment was also against “tyranny,” which meant the arbitrary rule of a monarch indifferent to the welfare of his or her subjects. Almost no Enlightenment thinkers openly rejected monarchy as a form of government – indeed, some Enlightenment thinkers befriended powerful kings and queens – but they roundly condemned cruelty and selfishness among individual monarchs. The perfect state was, in the eyes of most Enlightenment thinkers, one with an “enlightened” monarch at its head, presiding over a set of reasonable laws. Many Enlightenment thinkers thus looked to Great Britain, since 1689 ruled by a monarch who agreed to its written constitution and worked closely with an elected parliament, as the best extant model of enlightened rule.

Behind both the scientific worldview and the rejection of tyranny was a focus on the human mind’s capacity for reason. Reason is the mental faculty that takes sensory data and orders it into thoughts and ideas. The basic argument that underwrote the thought of the Enlightenment is that reason is universal and inherent to humans, and that if society could strip away the pernicious patterns of tradition, superstition, and ignorance, humankind would arrive naturally at a harmonious society. Thus, almost all of the major thinkers of the Enlightenment tried to get to the bottom of just that task: what is standing in the way of reason, and how can humanity become more reasonable?

Context and Causes

One of the major causes of the Enlightenment was the Scientific Revolution. It cannot be overstated how important the work of scientists was to the thinkers of the Enlightenment, because works like Newton’s Mathematical Principles demonstrated the existence of eternal, immutable laws of nature (ones that may or may not have anything to do with God) that were completely rational and understandable by humans. Indeed, in many ways the Enlightenment begins with Newton’s publication of the Principles in 1687.

Having thus established that the universe was rational, one of the major themes of the Enlightenment was the search for equally immutable and equally rational laws that applied to everything else in nature, most importantly human nature. How do humans learn? How might government be designed to ensure the most felicitous environment for learning and prosperity? If humans are capable of reason, why do they deviate from reasonable behavior so frequently?

Among the other causes of the Enlightenment, perhaps the most important was the significant growth of the urban literate classes, most notably what was called in France the bourgeoisie: the mercantile middle class. Ever since the Renaissance era, elites increasingly acquired at least basic literacy, but by the eighteenth century even artisans and petty merchants in the cities of Central and Western Europe sent their children (especially boys) to schools for at least a few years. There was a real reading public by the eighteenth century that eagerly embraced the new ideas of the Enlightenment and provided a book market for both the official, copyrighted works of Enlightenment philosophy and pirated, illegal ones. That same reading public also eagerly embraced the quintessential new form of fiction of the eighteenth century: the novel, with the reading of novels becoming a major leisure activity of the period.

Thus, the Enlightenment thought took place in the midst of what historians call the “growth of the public sphere.” Newspapers, periodicals, and cheap books became very common during the eighteenth century, which in turn helped the ongoing growth of literacy rates. Simultaneously, there was a full-scale shift away from the sacred languages to the vernaculars (i.e. from Latin to English, Spanish, French, etc.)., which in turn helped to start the spread of the modern state-sponsored vernaculars as spoken languages in regions far from royal capitals. For the first time, large numbers of people acquired at least a basic knowledge of the official language of their state rather than using only their local dialect. Those official languages allowed the transmission of ideas across entire kingdoms. For example, by the time the French Revolution began in the late 1780s, an entire generation of men and women was capable of expressing shared ideas about justice and politics in the official French tongue.

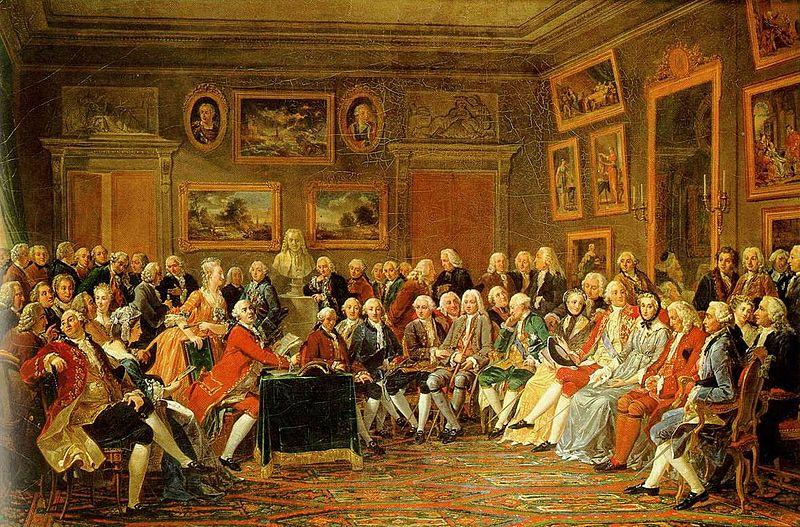

There were various social forums and spaces in which groups of self-styled “enlightened” men and women gathered to discuss the new ideas of the movement. The most significant of these were coffee houses in England and salons in France and Central Europe. Coffee houses, unlike their present-day analogs, charged an entry fee but then provided unlimited coffee to their patrons. Those patrons were from various social classes, and would gather together to discuss the latest ideas and read the periodicals provided by the coffee house (all while becoming increasingly caffeinated). Salons, which were common in the major cities of France and Germany, were more aristocratic gatherings in which major philosophers themselves would often read from their latest works, with the assembled group then engaging in debate and discussion. Salons were noteworthy for being led by women in most cases; educated women were thought to be the best moderators of learned discussion by most Enlightenment thinkers, men and women alike. Likewise, women writers were contributing members of salons, not just hostesses but participants in discussions and debates.

One of the best-known salons, run by Marie Thérèse Rodet Geoffrin, seated on the right. All of the men pictured are their actual likelinesses. Two are of particular note: seated under the marble bust is Jean le Rond D’Alembert, noted below, and the bust is of Voltaire (also described below), whose work is being read to the gathering in the picture.

Outside of the gatherings at coffee houses and salons, the ideas and themes of the Enlightenment reached much of the reading public through the easy availability of cheap print, and it is also clear that even regular artisans were conversant in many Enlightenment ideas. To cite a single example, one French glassworker, Jacques-Louis Menetra, left a memoir in which he demonstrated his own command of the ideas of the period and even claimed to have chatted over drinks with the great Enlightenment philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau. The major thinkers of the Enlightenment considered themselves to be part of a “republic of letters,” similar to the “republic of science” that played such a role in the Scientific Revolution. They wrote voluminous correspondence and often sent one another unpublished manuscripts. Thus, from the thinkers themselves participating in the republic of letters down to artisans trading pirated copies of enlightenment works, the new ideas of the period permeated much of European society.

Enlightenment Philosophes

The term most often used for Enlightenment thinkers is philosophe, meaning simply “philosopher” in French. Many of the most famous and important philosophes were indeed French, but there were major English, Scottish, and Prussian figures as well. Some of the most noteworthy philosophes included the following.

John Locke: 1637 – 1704

Locke was an Englishman who, along with Newton, was among the founding figures of the Enlightenment itself. Locke was a great political theorist of the period of the English Civil Wars and Glorious Revolution, arguing that sovereignty was granted by the people to a government but could be revoked if that government violated the laws and traditions of the country. He was also a major advocate for religious tolerance; he was even bold enough to note that people tended to be whatever religion was prevalent in their family and social context, so it was ridiculous for anyone to claim exclusive access to religious truth.

Locke was also the founding figure of Enlightenment educational thought, arguing that all humans are born “blank slates” – Tabula Rasa in Latin – and hence access to the human faculty of reason had entirely to do with the proper education. Cruelty, selfishness, and destructive behavior were because of a lack of education and a poor environment, while the right education would lead anybody and everybody to become rational, reasonable individuals. This idea was hugely inspiring to other Enlightenment thinkers, because it implied that society could be perfected if education was somehow improved and rationalized.

Voltaire: 1694 – 1778

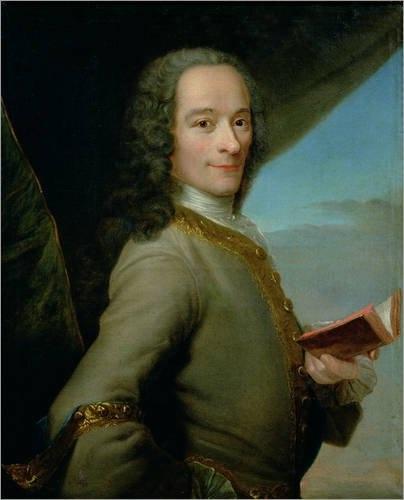

The pen name of François-Marie Arouet, Voltaire was arguably the single most influential figure of the Enlightenment. The greatest novelist, poet, and philosopher of France during the height of the Enlightenment period, Voltaire became famous across Europe for his wit, intelligence, and moral battles against what he perceived as injustice and superstition.

In addition to writing hilarious novellas lambasting everything from Prussia’s obsession with militarism to the idiotic fanaticism of the Spanish Inquisition, Voltaire was well known for publicly intervening against injustice. He wrote essays and articles decrying the unjust punishment of innocents and personally convinced the French king Louis XV to commute the sentences of certain individuals unjustly convicted of crimes. He was also an amateur scientist and philosopher – he wrote many of the most important articles in the “official” handbook of the Enlightenment, the Encyclopedia (described below).

Voltaire

While he was a tireless advocate of reason and justice, It is also important to note the ambiguities of Voltaire’s philosophy. He was a deep skeptic about human nature, despite believing in the existence and desirability of reason. He acknowledged the power of ignorance and outmoded traditions to govern human behavior, and he expressed considerable skepticism that society could ever be significantly improved. For example, despite his personal disdain for Christian (especially Catholic) institutions, he noted that “if God did not exist, it would be necessary to invent Him,” because without a religious structure shoring up their morality, the ignorant masses would descend into violence and barbarism.

Emilie de Châtelet: 1706 – 1749

A major scientist and philosopher of the period, Châtelet published works on subjects as diverse as physics, mathematics, the Bible, and the very nature of happiness. Perhaps her best-known work during her lifetime was an annotated translation of Newton’s Mathematical Principles which explained the Newtonian concepts to her (French) readers. Despite the gendered biases of most of her scientific contemporaries, she was accepted as an equal member of the “republic of science.” In Châtelet the link between the legacy of the Scientific Revolution and the Enlightenment is clearest: while her companion (and lover) Voltaire was keenly interested in science and engaged in modest efforts at his own experiments, Châtelet was a full-fledged physicist and mathematician.

The Encyclopedia of Diderot and D’Alembert (1751)

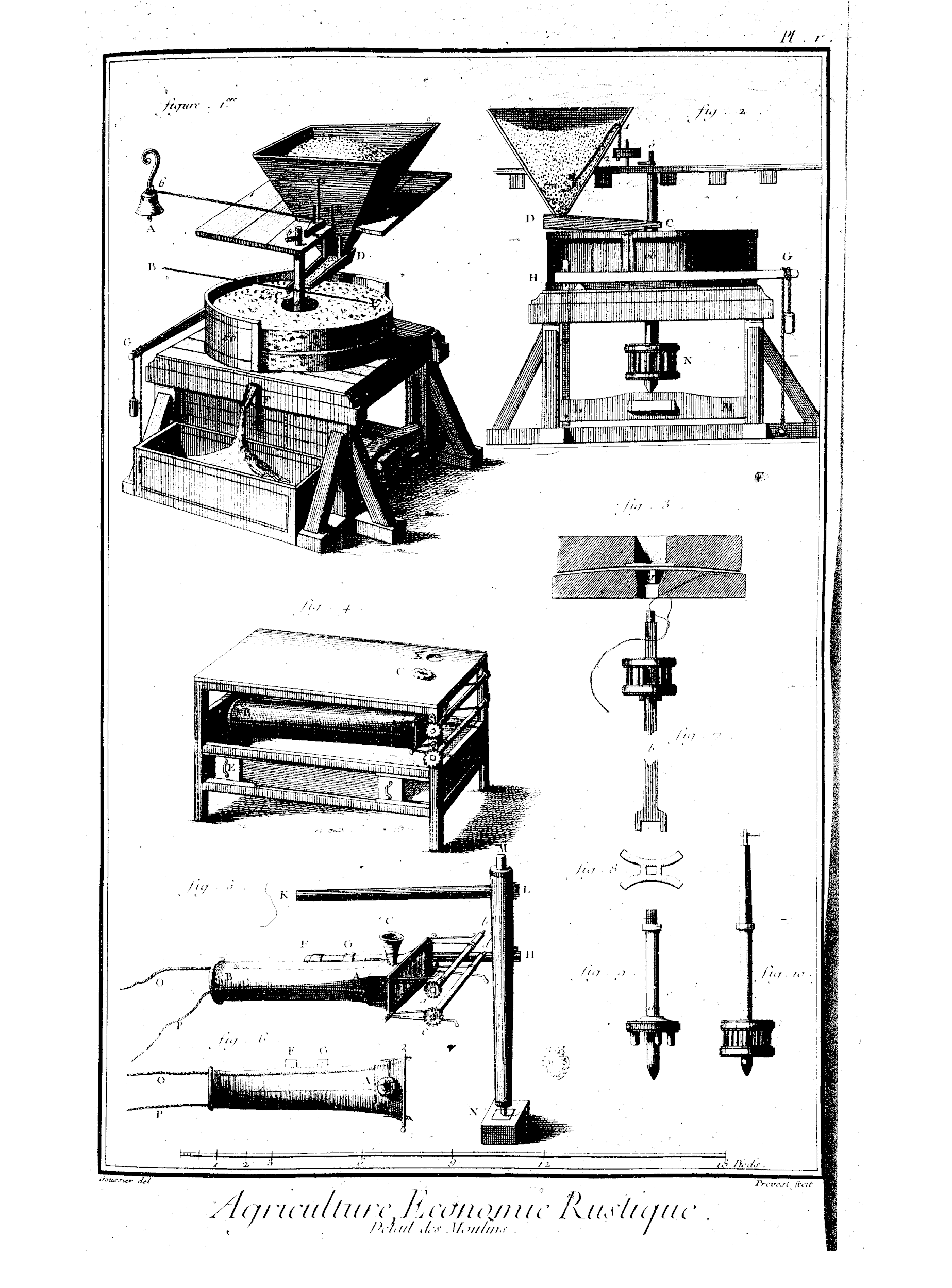

The brainchild of two major French philosophes, the Encyclopedia was a full-scale attempt to catalog, categorize, and explain all of human knowledge. While its co-inventors, Jean le Rond D’Alembert and Denis Diderot, themselves wrote many of the articles, the majority were written by other philosophes, including (as noted above) Voltaire. The first volume was published in 1751, with other volumes following. In the end the Encyclopedia consisted of 28 volumes containing 60,000 articles with 2,885 illustrations. While its volumes were far too expensive for most of the reading public to access directly, pirated chapters ensured that its ideas reached a much broader audience.

One of the illustrations from the Encyclopedia, in this case diagrams of (at the time, state of the art) agricultural equipment.

The Encyclopedia was explicitly organized to refute traditional knowledge, namely that provided by the church and (to a lesser extent) the state. The claim was that the application of reason to any problem could result in its solution. It also attempted to be a technical resource for would-be scientists and inventors, not only describing aspects of science but including detailed technical diagrams of everything from windmills to mines. In short, the Encyclopedia was intended to be a kind of guide to the entire realm of human thought and technique – a cutting-edge description of all of the knowledge a typical philosophe might think necessary to improve the world.

David Hume: 1711 – 1776

Hume was the major philosopher associated with the Scottish Enlightenment, an outpost of the movement centered in the Scottish capital of Edinburgh. Hume was one of the most powerful critics of all forms of organized religion, which he argued smacked of superstition. To him, any religion based on “miracles” was automatically invalid, since miracles do not happen in an orderly universe knowable through science. In fact, Hume went so far as to suggest that belief in a God who resembled a kind of omnipotent version of a human being, with a personality, intentions, and emotions, was simply an expression of primitive ignorance and fear early in human history, as people sought an explanation for a bewildering universe.

Hume also expressed enormous contempt for the common people, who were ignorant and susceptible to superstition. Hume is important to consider because he embodied one of the characteristics of the Enlightenment that often seems the most surprising from a contemporary perspective, namely the fact that it did not champion the rights, let alone anything like the right to political expression, of regular people. To a philosopher like Hume, the average commoner (whether a peasant or a member of the poor urban classes) was so mired in ignorance, superstition, and credulity that he or she should be held in check and ruled by his or her betters.

Adam Smith: 1723 – 1790

Smith was another Scotsman who did his work in Edinburgh. He is generally credited with being the first real economist: a social scientist devoted to analyzing how markets function. In his most famous work, The Wealth of Nations, Smith argued that a (mostly) free market, one that operated without undue interference of the state, would naturally result in never-ending economic growth and nearly universal prosperity. His targets were the monopolies and protectionist taxes and tariffs that limited trade between nations; he argued that if states dropped those kind of burdensome practices, the market itself would increase wealth as if the general prosperity of the nation was lifted by an “invisible hand.”

Smith’s importance, besides founding the discipline of economics itself, was that he applied precisely the same kind of Enlightenment ideas and ideals to market exchange as did the other philosophes to morality, science, and so on. Smith, too, insisted that something in human affairs – economics – operated according to rational and knowable laws that could be discovered and explained. His ideas, along with those of David Ricardo, an English economist a generation younger than Smith, are normally considered the founding concepts of “classical” economics.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712 – 1778)

Rousseau was the great contrarian philosophe of the Enlightenment. He rose to prominence by winning an essay contest in 1749, penning a scathing critique of his contemporary French society and claiming that its so-called “civilization” was a corrupt facade that undermined humankind’s natural moral character. He went on to write both novels and essays that attracted enormous attention both in France and abroad, claiming among other things that children should learn from nature by experiencing the world, allowing their natural goodness and character to develop. He also championed the idea that political sovereignty arose from the “general will” of the people in a society, and that citizens in a just society had to be fanatically devoted to both that general will and to their own moral standards (Rousseau claimed, in a grossly inaccurate and anachronistic argument, that ancient Sparta was an excellent model for a truly enlightened and moral polity). Rousseau’s concept of a moralistic, fanatical government justified by a “general will” of the people would go on to become of the ideological bases of the French Revolution that began just a decade after his death.

Politics and Society

The political implications of the Enlightenment were surprisingly muted at the time. Almost every society in Europe exercised official censorship, and many philosophes had to publish their more provocative works using pseudonyms, sometimes resorting to illegal publishing operations and book smugglers in order to evade that censorship (not to mention their own potential arrest). Likewise, one of the important functions of the salons mentioned above was in providing safe spaces for Enlightenment ideas, and many of the women who ran salons supported (sometimes financially) controversial projects like the Encyclopedia in its early stages. In general, philosophes tended to openly attack the most egregious injustices they perceived in royal governments and the organized churches, but at the same time their skepticism about the intellectual abilities of the common people was such that almost none of them advocated a political system besides a better, more rational version of monarchy. Likewise, philosophes were quick to salute (to the point of being sycophantic at times) monarchs who they thought were living up to their hopes for the ideal of rational monarchy.

In turn, various monarchs and nobles were attracted to Enlightenment thought. They came to believe in many cases in the essential justice of the arguments of the philosophes and did not see anything contradictory between the exercise of their power and enlightenment ideas. That said, monarchs tended to see “enlightened reforms” in terms of making their governments more efficient. They certainly did not renounce any of their actual power, although some did at least ease the burdens on the serfs who toiled on royal lands.

One major impact that Enlightenment thought unquestionably had on European (and, we should note, early American) politics was in the realm of justice. A noble from Milan, Cesare Bonesana, wrote a brief work entitled On Crimes and Punishment in 1764 arguing that the state’s essential duty was the protection of the life and dignity of its citizens, which to him included those accused of crimes. Among other things, he argued that rich and poor should be held accountable before the same laws, that the aim of the justice system should be as much to prevent future crimes as to punish past ones, and that torture was both barbarous and counter-productive. Several monarchs in the latter part of the eighteenth century did, in fact, ban torture in their realms, and “rationalized” justice systems slowly evolved in many kingdoms during the period.

Perhaps the most notable “enlightened monarch” was Frederick II (the Great) of Prussia (r. 1740 – 1786). A great lover of French literature and philosophy, he insisted only on speaking French whenever possible (he once said that German was a language only useful for talking to one’s horse), and he redecorated the Prussian royal palace in the French style, in which he avidly hosted Enlightenment salons. Frederick so impressed the French philosophes that Voltaire came to live at his palace for two years until the two of them had a falling out. Inspired by Enlightenment ideas, he freed the serfs on royal lands and banned the more onerous feudal duties owed by serfs owned by his nobles. He also rationalized the royal bureaucracy, making all applicants pass a formal exam, which provided a limited path of social mobility for non-nobles.

Another ruler inspired by Enlightenment ideas was the Tsarina Catherine the Great (r. 1762 – 1796) of Russia. Catherine was a correspondent of French philosophes and actively cultivated Enlightenment-inspired art and learning in Russia. Hoping to increase the efficiency of the Russian state, she expanded the bureaucracy, reorganized the Russian Empire’s administrative divisions, and introduced a more rigorous and broad education for future officers of the military. She also created the first educational institution for girls in Russia, the Smolny Institute, admitting the daughters of nobles and, eventually, well-off commoners (ironically, given her own power, the Institute trained noble girls to be dutiful, compliant wives rather than would-be leaders).

Catherine was not just an admirer of Enlightenment philosophy, but an active member of the “Republic of Letters,” writing a series of plays, memoirs, and operas meant to celebrate Russian culture (not least against accusations of Russian backwardness by writers in the West), as well as her own success as a ruler. Her enthusiasm for the Enlightenment dampened considerably, however, as the French Revolution began in 1789, and while Russian nobles found their own privileges expanded, the vast majority of Russian subjects remained serfs. Like Frederick of Prussia, Catherine’s appreciation for “reason” had nothing to do with democratic impulses.

One major political theme to emerge from the Enlightenment that did not require the goodwill of monarchs was the idea of human rights (or “the rights of man” as they were generally known at the time). Emerging from a combination of rationalistic philosophy and what historians describe as new “sensibilities” – above all the recognition of the shared humanity of different categories of people – concepts of human rights spread rapidly in the second half of the eighteenth century. In turn, they fueled both demands for political reform and helped to inspire the vigorous abolitionist (anti-slavery) movement that flourished in Britain in particular. Just as torture came to be seen by almost all Enlightenment thinkers as not just cruel, but archaic and irrational, so slavery went from an unquestionable economic necessity to a loathsome form of ongoing injustice. Just as the idea of human rights would soon inspire both the American and French Revolutions in the closing decades of the eighteenth century, the antislavery movements of the time would see many of their objectives achieved in the first few decades of the nineteenth (Britain would ban the slave trade in 1807 and slavery itself in 1833, although it would take the American Civil War in the 1860s to end slavery in the United States).

That concern for rights did not, with a few noteworthy exceptions, extend to women. Just as the Scientific Revolution had abandoned actual empirical methods entirely in merely endorsing ancient stereotypes about female inferiority, the vast majority of male philosophes either ignored women in their writing entirely or argued that women had to be kept in a subservient social position. The same philosophes who eagerly attended women-run salons often wrote against educated women relating to men as peers. The great works of early feminism that emerged in the late Enlightenment, such as the English writer Mary Wollstencraft’s Vindication of the Rights of Woman in 1791, were viciously attacked and then largely ignored until the modern feminist movement forced the issue the better part of a century later.

The Radical Enlightenment and The Underground

While the mainstream Enlightenment was definitely an elite affair conducted in public, there were other elements to it. The so-called Radical Enlightenment (the term was invented by historians, not people involved in it) had to do with the ideas too scandalous for mainstream philosophes to support, like outright atheism. One example of this phenomenon was the emergence of Freemasonry, “secret,” although not difficult to find for most male European elites, groups of like-minded Enlightenment thinkers who gathered in “lodges” to discuss philosophy, make political connections, and socialize.

Some Masonic lodges were associated with a much more widespread part of the “radical” Enlightenment: the vast underground world of illegal publishers and smugglers. In areas with relatively relaxed censorship like the Netherlands and Switzerland, numerous small printing presses operated throughout the eighteenth century, cranking out illegal literature. Some of this literature consisted of the banned works of major philosophes themselves, but much of it was simply pirated and “dumbed-down” versions of things like the Encyclopedia. This illegal industry supplied the reading public, especially the reading public with little money to spend on books, with their essential access to Enlightenment thought.

For example, as noted above, an actual volume (let alone the entire multi-volume set) of the Encyclopedia was much too expensive for a common artisan or merchant to afford. Such a person could, however, afford a pamphlet-sized, pirated copy of several of the articles from the Encyclopedia that might interest her. Likewise, many works that were clearly outside of the acceptable bounds of legal publishing at the time (including both outright attacks on Christianity as a fraud as well as a shocking amount of pornography) were published and smuggled into places like France, England, and Prussia from the underground publishing houses. Perhaps the greatest impact of the Radical Enlightenment at the time is that it made mainstream Enlightenment ideas – however poorly summarized they might have been in pirated works – more accessible to far more of European society as a whole than they would have been otherwise.

Conclusion: Implications of the Enlightenment

The noteworthy philosophes of the Enlightenment rarely attacked outright the social hierarchy that they were part of. The abuses of the church, the ignorance of the nobility, even the injustices of kings might be fair game for criticism, but none of the better-known philosophes called for the equivalent of a political revolution. Only Rousseau was bold enough to advocate a republican form of government as a viable alternative to monarchy, and his political ideas were far less well-known during his lifetime than were his ruminations on education, nature, and morality. Even Kant’s essay celebrated what he described as the “public use of reason,” namely intellectuals exchanging ideas, while defending the authoritarian power of the (Prussian, in his case) king to demand that his subjects “obey!”

The problem was that even though most of the major figures of the Enlightenment were themselves social elites, their thought was ultimately disruptive to the Christian society of orders. Almost all of the philosophes claimed that the legitimacy of a monarch was based on their rule coinciding with the prosperity of the nation and the absence of cruelty and injustice in the laws of the land. The implication was that people have the right to judge the monarch in terms of his or her competence and rationality. Likewise, one major political and social structure that philosophes did attack was the fact that nobles enjoyed vast legal privileges but had generally done nothing to deserve those privileges besides being born a member of a noble family. In contrast, philosophes were quick to point out that many members of the middle classes were far more intelligent and competent than was the average nobleman.

In addition, despite the inherent difficulty of publishing against the backdrop of censorship, philosophes did much to see that organized religion itself was undermined. The one stance all of the major Enlightenment thinkers agreed on regarding religion was that “revealed” religion – religion whose authority was based on miracles – was nonsense. According to the philosophes, the history of miracles could be disproved, and contemporary miracles were usually experienced by lunatics, women, and the poor (and were thus automatically suspect from their elite, male perspective). Miracles, by their very nature, purported to violate natural law, and according to the very core principles of Enlightenment thought, that simply was not possible.

Thus, the Enlightenment did more to disrupt the social and political order by the late eighteenth century than most of its members ever intended. The most obvious and spectacular expression of that disruption took place in a pair of political revolutions: first in the American colonies of Great Britain in the 1770s, then in France starting in the 1780s. In both of those revolutions, ideas that had remained in the abstract during the Enlightenment were made manifest in the form of new constitutions, laws, and principles of government, and in both cases, one of the byproducts was violent upheaval.

Image Citations (Wikimedia Commons):

Salon of Mme. Geoffrin – Public Domain

Encyclopedia Illustration – Public Domain