Chapter 12: The Soviet Union and the Cold War

The Cold War

At the height of Soviet power in the late 1960s, one-third of the world’s population lived in communist countries. The great communist powers of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) and the People’s Republic of China loomed over a vast swath of Eurasia, while smaller countries occasionally erupted in revolution. Non-aligned countries like India were often as sympathetic to the “Soviet Bloc” (i.e. countries allied with or under the control of the USSR) as they were to the United States and the other major capitalist countries. Even in the capitalist countries of the West, intellectuals, students, and workers often sympathized with communism as well, despite the apparent mismatch between the Utopian promise of Marxism and the reality of a police state in the USSR.

This global split between communist and capitalist was only possible because of the vast might of the USSR. The threat of world war terrified every sane person on the planet, but beyond that, the threat of conventional military intervention by the Soviets was almost as threatening. The USSR controlled the governments of every Eastern European country, with the strange exception of Yugoslavia, and it had considerable influence almost everywhere in the globe. Its factories churned out military hardware at an enormous rate, even as its scientists proved themselves the equal of anything the west could produce and its athletes often defeated all challengers at the Olympics every four years.

Behind the façade of strength and power, however, the USSR was one of the strangest historical paradoxes of all time. It was a country whose official political ideology, Marxism-Leninism, proclaimed an end to class warfare and the stated goal of achieving true communism, a worker’s state in which everyone enjoyed the fruits of science and industrialism and no one was left behind. In reality, the nation was in a perpetual state of economic stagnation, with its citizens enjoying dramatically lower standards of living than their contemporaries in the west and workers toiling harder and for fewer benefits than did many in the west. Marxism-Leninism was officially hostile to imperialism, and yet the USSR controlled the governments of most of its “allied” nations after World War II. Of all forms of government, communism was supposed to be the most genuinely democratic, responding to the will of the people instead of false representatives bought with the money of the rich, and yet decision-making rested in the hands of high-level member of the communist party, the so-called apparatchiks, or arch-bureaucrats. Finally, Marxism-Leninism was officially a political program of peace, yet nothing received so much attention or priority in the USSR as did military power.

Stalinism

The Bolshevik party rose to power against the backdrop of the anarchy surrounding Russia’s disastrous military position in the latter part of World War I. Once the Bolsheviks were firmly in power by 1922, they embarked on a fascinating and almost unprecedented series of political and social experiments. After all, no country in the history of the planet to that point had undergone a successful communist revolution, so there was no precedent for how a socialist society was supposed to be organized. Facing a terrible economic crisis from the years of war, the Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin launched the New Economic Policy, which allowed limited market exchange of goods and foodstuffs, even as the state supported a renaissance in the arts and literature. For a few years, not only did standards of living rise, but there was a flowering of innovative creative energy as artists and intellectuals explored what it might mean to live in the country of the future.

Lenin had driven the revolution forward, and he oversaw the social and economic experiments that followed the war. He died in 1924, however, inaugurating a struggle within the Bolshevik leadership to succeed him. In 1927, Joseph Stalin politically defeated his enemies (most importantly the Bolshevik leaders Trotsky and Zinoviev, two of Lenin’s closest allies before his death) and consolidated total control of the state. Officially, Stalin was the “Premier” of the communist party – “the first” – overseeing its central decision-making committee, the Politburo. Unofficially, Stalin’s control of the top level of the party translated into pure autocracy, not hugely dissimilar in nature to the power of the Tsar before the revolution.

Before his rise to power, Stalin’s position in the Russian Communist Party had been relatively innocuous; he was its secretary, a position of little direct power but enormous potential influence. In order to achieve an appointment to a given position within the party, other members of the party had to go through Stalin. He shrewdly used this fact to cement political relationships and influence, so that by Lenin’s death he was well-positioned to make a power grab himself. Lenin suffered a series of strokes in the early 1920s, giving Stalin the opportunity to build up his power base without opposition, even though Lenin himself was worried about Stalin’s dictatorial tendencies.

Stalin is a much more enigmatic figure than Hitler, to whom he is often compared thanks to their respective legacies of mass murder. Stalin did not write manifestos about his beliefs, nor did he leave behind many documents or letters that might help historians reconstruct his motivations. Biographers have had to rely on the accounts of people who knew Stalin rather than having access to troves of personal records. He also changed his mind frequently and did not stick to consistent patterns of behavior or decision-making, making it difficult to pin down his essential beliefs or goals. His only overarching personality trait was tremendous paranoia: he almost always felt himself surrounded by potential traitors and enemies. He once informed his underlings that “every communist is a possible hidden enemy. And because it is not easy to recognize the enemy, the goal is achieved even if only five percent of those killed are truly enemies.”

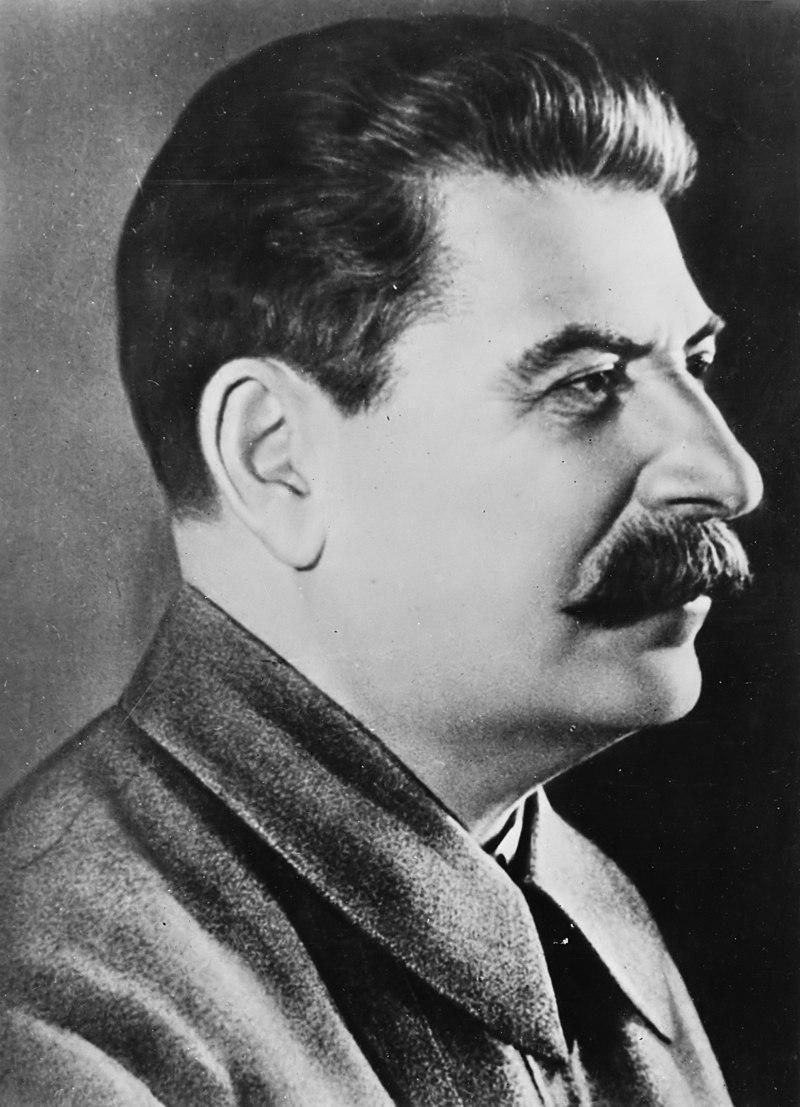

Stalin

Stalin’s paranoia was reflected in his ruthless policies. Starting at the end of the 1920s, Stalin forced through massive change to the Soviet economy and society while periodically killing off anyone he could imagine being a threat or enemy. Communism was “supposed” to spread around the world after an initial revolutionary outburst, but instead it was stuck in one place, “socialism in one country,” in Stalin’s words, which he believed necessitated a massive industrial buildup. The only thing that benefited from Stalin’s oversight was the military, which grew dramatically and, for the first time since the Napoleonic Wars, achieved a level of parity with the west.

Of his many destructive policies, Stalin is perhaps best remembered for the purges. “Purging” consisted of rounding up and executing members of the communist party, the army, or even the police forces themselves. Normally, Stalin’s agents would use torture to force the hapless victims to confess to outlandish charges like conspiring with Germany or (later) the United States to bring down the Soviet Union from within. His secret police force, the NKVD (its Russian acronym – it was later changed to KGB) often following direct orders from Stalin himself, eliminated uncounted thousands more. Thus, even at the highest levels of power in the USSR, no one was safe from Stalin’s paranoia.

Stalin relied on the NKVD to carry out the purges, targeting better-off peasants known as kulaks, then the Old Bolsheviks (who had taken part in the revolution itself), army officers, middle-ranking communist party members, and finally, tens of thousands of regular citizens caught in the grotesque machinery of accusation and punishment that plagued the country in the second half of the 1930s. Every purge was designed to, at least in part, purge the past purgers, blaming them for “excesses” that had killed innocent people – this of course simply led to the murder of more innocents. So many people disappeared that most Soviets came to believe that the NKVD was everywhere, that everyone was an informer, and that everything was bugged. In addition to outright murder, thousands more were imprisoned in labor camps known as gulags, almost all of which were located in the frigid northern regions of Siberia. The total number of victims is estimated conservatively at 700,000, which does not count the hundreds of thousands deported to the gulags.

While emblematic of Stalin’s tyranny, the purges did not result in nearly as many deaths as did his other policies. Beginning in 1928, Stalin ordered a definitive break with the limited market exchange of the New Economic Policy, announcing a “Great Turn” towards industrialization, state-controlled economics, and agricultural reorganization. Starting in 1929, the Soviet state imposed the collectivization of agriculture, forcing millions of peasants to abandon their farms and villages and move to gigantic new collective farms. Collectivization required peasants to meet state-imposed quotas, which were immediately set at unachievable levels. In the winter of 1932 – 1933 in particular, peasants across the USSR (and especially in the Ukraine) starved to death – probably around 3 million people died of starvation, and the collectivization process resulted in another 6 – 10 million deaths including those who were executed for resisting. Thus, the total deaths were probably over 10 million. Despite falling abysmally short of its production goals, where collectivization “succeeded” was in destroying the age-old bonds between the peasants and the land. In the future, Soviet peasants would be a resentful and inefficient class of farm workers rather than peasants rooted in the land who identified with traditional values.

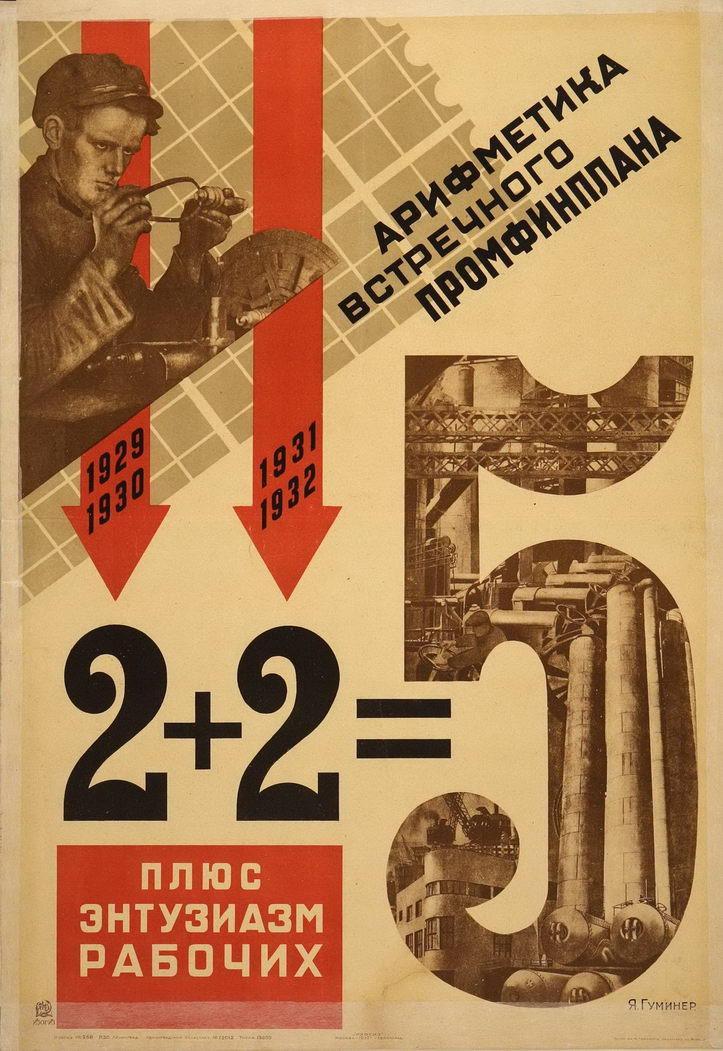

Acknowledging the vast gap between the Soviet Union’s industrial capacity and that of the west, Stalin also introduced the Five-Year Plans, in which sky-high production quotas were set for heavy industry. While those quotas were never actually met and thousands died in the frenzy of industrial buildup, the Five-Year Plans (three of which took place before World War II began) were successful as a whole in achieving near parity with the western powers in terms of industrial capacity. One of the only aspects of communist ideology that was reflected in reality in the USSR was that industrial workers, while obliged to toil in conditions far from a “worker’s paradise,” were at least spared the worst depredations of the purges and did not face outright starvation.

Stalin’s overriding goals were twofold: secure allies abroad against the growing power of Germany (and, to an extent, Japan), and drag the USSR into the industrial age. Despite the turmoil of his murderous campaigns, he succeeded on both counts. While remaining deeply hostile to the western powers, the Soviet state under Stalin did end the Soviet Union’s pariah status, receiving official diplomatic recognition from the US and France in 1933. The Five-Year Plans were part of the USSR’s new “command economy,” one in which every conceivable commodity was produced based on quotas imposed within the vast party bureaucracy in Moscow. That approach to economic planning was disastrous in the long run, but in the short run it did succeed in industrializing the USSR. On the eve of World War II, the USSR had become the third-largest industrial power in the world after the United States and Germany, and was counted among the major political powers of not just Europe, but the world.

World War II and its Aftermath

Thus, at a terrible human cost, Stalin’s policies did transform the USSR into a semblance of a modern state by the eve of World War II – “just in time” as it turned out. During the war the USSR bore the brunt of German military power. More than 25 million Soviets died on the eastern front, soldiers and civilians alike, and it was through the incredible sacrifice of the Soviet people that the German army was finally broken and driven back. In the aftermath of World War II, Stalin’s power was unshakable. During the war, he had played the role of the powerful, protective “uncle” of the Soviet people, and after victory was achieved he enjoyed a period of genuine popularity, especially as returning Soviet soldiers were given good positions in the bureaucracy.

During the war, the one thing that tied Britain, the US, and the USSR together in alliance was their shared enemy, Germany, not shared perspectives on a desirable postwar outcome besides German defeat. The war required them to work together, however, and that included making compromises that would in some cases haunt the postwar period. In 1943, after the tide of the war had shifted against Germany but well before the end was in sight, the “Big Three” leaders of Britain, the US, and the USSR met in Tehran to discuss the war and what would be done afterwards. There, Stalin insisted that the territory seized from Poland by the USSR in 1939 would remain in Soviet hands: Poland would thus shrink enormously. Roosevelt and Churchill, well aware of the critical role then being played by Soviet troops, were not in a position to insist otherwise.

In 1944, a team of politicians and economists from several Allied nations met in New Hampshire and devised the basis of the postwar economic order, the Bretton Woods Agreement. That agreement fixed the dollar as the monetary reserve of the western world, created the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank to stabilize the international economy, and fixed currency exchange rates. This plan initially included the Soviets, who would thus be eligible for financial support in addressing the devastation wrought by Germany (as noted below, however, the USSR pulled out in 1948, thereby driving home an economic as well as political divide between east and west).

In January of 1945, when the end was finally in sight and Soviet forces already occupied most of Eastern Europe, Stalin stipulated that the postwar governments in Eastern Europe would need to be “friendly” to the Soviet Union, an ambiguous term whose practical meaning suggested dominance by communist parties. Churchill and Roosevelt agreed on the condition that Stalin promised to support free elections, something Stalin never intended to allow. The leaders also agreed to divide Germany into different zones until such time as they could determine how to allow the Germans, purged of Nazism they hoped, to have self-government again.

In part, Britain and the US gave in to Soviet demands because of the incredible sacrifice of the Soviet people in the war; 90% of the casualties on the Allied side up to 1944 were Soviets (mostly Russians, but including millions of Ukrainians and Central Asians as well). Until 1945, Roosevelt assumed the United States would need Soviet help in bringing about the final defeat of Japan as well. Each side tried to avoid antagonizing the other, especially while the war continued, even though they privately recognized that there were incompatible visions of postwar European reorganization at stake.

Despite those incompatible ideas, many political leaders (and regular citizens) across the globe hoped that the postwar order would be fundamentally different than its prewar analog. Fundamental to that vision was the creation of an official international body whose purpose was the prevention of armed conflict and the pursuit of peaceful and productive policies around the world: the United Nations, the second attempt at an international coordinating organization after the pitiful failure of the League of Nations in the 1920s and 1930s. The UN was founded in 1945 as a body of arbitration and, when necessary, enforcement of internationally-agreed upon policies, seeing its first major role in the Nuremberg Trials of the surviving Nazi leaders. Its Security Council was authorized to deploy military force when necessary, but its very reason to be was to prevent war from being used as a tool of political aggrandizement. The Soviet Union joined the western powers as a founding member of the UN, and there were at least some hopes that it would oversee a just and equitable postwar political order.

The Cold War

Despite the foundation of the UN, and the fact that both the US and USSR were permanent members of the Security Council, the divide between them undermined the possibility of global unity. Instead, by the late 1940s, the world was increasingly split into the two rival “camps” of the Cold War. The term itself refers to the decades-long rivalry between the two postwar “superpowers,” the United States and the Soviet Union. This was a conflict that, fortunately for the human species, never became a “hot” war. Both sides had enormous nuclear arsenals by the 1960s that would have ensured that a “hot” war would almost certainly see truly unprecedented destruction, up to and including the actual possibility of the extinction of the human species (the American government invented a memorable phrase for this known as M.A.D.: Mutually Assured Destruction). Instead, both nations had enough of a collective self-preservation instinct that the conflict worked itself out in the form of technological and scientific rivalry, an enormous and ongoing arms race, and “proxy wars” fought elsewhere that did not directly draw both sides into a larger conflict.

The open declaration of the Cold War, as it were, consisted of doctrines and plans. In 1947 the US issued the Truman Doctrine, which pledged to help people resist communism wherever it appeared – the rhetoric of the doctrine was about the defense of free people who were threatened by foreign agents, but as became very clear over the next few decades, it was more important that people were not communists than they were “free” from dictatorships. The Truman Doctrine was born out of the idea of “containment,” of keeping communism limited to the countries in which communist takeovers had already occurred. The immediate impetus for the doctrine was a conflict raging in Greece after WWII, in which the communist resistance movement that had fought the Nazis during the war sought to overthrow the right-wing, royalist government of Greece in the aftermath. Importantly, while both the British and then the US supported the Greek government, the USSR did not lend any aid to the communist rebels, rightly fearing that doing so could lead to a much larger war. Furious at what he regarded as another instance of western capitalist imperialism, however, Stalin pulled the USSR out of the Bretton Woods economic agreement in early 1948.

The Truman Doctrine was closely tied to the fear of what American policy-makers called the “Domino Theory”: if one nation “fell” to communism, it was feared, communism would spread to the surrounding countries. Thus, preventing a communist takeover anywhere, even in a comparatively small and militarily insignificant country, was essential from the perspective of American foreign policy during the entire period of the Cold War. That theory was central to American policy from the 1950s through the 1980s, deciding the course of politics, conflicts, and wars from Latin America to Southeast Asia.

Along with the Truman Doctrine, the United States introduced the Marshall Plan in 1948, named for the American secretary of state at the time. The Marshall Plan consisted of enormous American loans to European countries trying to rebuild from the war. European states also founded a intra-European economic body called the Organization of European Economic Cooperation that any country accepting loans was obliged to join. Stalin regarded the OEEC as a puppet of the US, so he banned all countries under Soviet influence from joining, and hence from accepting loans. Simultaneously, the Soviets were busy extracting wealth and materials from their new puppets in Eastern Europe to help recover from their own war losses. The legacy of the Marshall Plan, the OEEC, and Soviet policy was to create a stark economic division: while Western Europe rapidly recovered from the war, the East remained poor and comparatively backwards.

Already by 1946, in the words of Winston Churchill, the “iron curtain” had truly fallen across Eastern Europe. Everywhere, local communist parties at first ruled along with other parties, following free elections. Then, with the aid of Soviet “advisers,” communists from Poland to Romania pushed other parties out through terror tactics and legal bans on non-communist political organizations. Soon, each of the Eastern European states was officially pledged to cooperate with the USSR. Practically speaking, this meant that every Eastern European country was controlled by a communist party that took its orders directly from Moscow – there was no independent political decision-making allowed.

The major exception was Yugoslavia. Ironically, the one state that had already been taken over by a genuine communist revolution was the one that was not a puppet of the USSR. During the war, an effective anti-German resistance was led by Yugoslav communists, and in the aftermath they succeeded in seizing power over the entire country. Tito, the communist leader of Yugoslavia, had great misgivings about the Soviet takeover of the rest of Eastern Europe, and he and Stalin angrily broke with one another after the war. Thus, Yugoslavia was a communist country, but not one controlled by the USSR.

In turn, it was Stalin’s anger that Yugoslavia was outside of his grasp that inspired the Soviets to carry out a series of purges against the communist leadership of the Eastern European countries now under Soviet domination. Soviet agents sought “Titoists” who were supposedly undermining the strength of commitment to communism. Between 1948 and 1953 more communists were killed by other communists than had died at the hands of the Nazis during the war (i.e. in terms of direct Nazi persecution of communists, not including casualties of World War II itself). Communist leaders were put on show trials, both in their own countries and sometimes after being hauled off to Moscow, where they were first tortured into confessing various made-up crimes (collaborating with western powers to overthrow communism was a popular one), then executed. It is worth noting that this period, especially the first few years of the 1950s, saw anti-Semitism become a staple of show trials and purges as well, as latent anti-Semitic sentiments came to the surface and Jewish communist leaders suffered a disproportionate number of arrests and executions, often accused of being “Zionists” secretly in league with the west.

Simultaneously, the world was dividing into the two “camps” of the Cold War. The zones of occupation of Germany controlled by the US, France, and Britain became the new nation of the Federal Republic of Germany, known as West Germany, while the Soviet-controlled zone became the German Democratic Republic, or East Germany. Nine western European countries joined the US in forming the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, NATO, whose stated purpose was the defense of each of the member states from invasion – understood to be the invasion of Western Europe by the USSR. The USSR tested its first atomic bomb in August of 1949, thereby establishing the stakes of the conflict: the total destruction of human life. And, finally, by 1955 the Soviets had formalized their own military system with the Warsaw Pact, which bound together the Soviet Bloc in a web of military alliances comparable to NATO.

In hindsight, it is somewhat surprising that the USSR was not more aggressive in the early years of the Cold War, making no overt attempts to sponsor communist takeovers outside of Eastern Europe. The one direct confrontation between the two camps took place between May of 1948 and June of 1949, when the Soviets blockaded West Berlin. The city of Berlin was in East Germany, but its western “zones” remained in the hands of the US, Britain, and France, the phenomenon a strange relic of the immediate aftermath of the war. As Cold War tensions mounted, Stalin ordered the blockade of all supplies going to the western zones. The US led a massive ongoing airlift of food and supplies for nearly a year while both sides studiously avoided armed confrontation. In the end, the Soviets abandoned the blockade, and West Berlin became a unique pocket of the western camp in the midst of communist East Germany.

It is worth considering the fact that Europe had been, scant years earlier, the most powerful region on Earth, ruling the majority of the surface of the globe. Now, it was either under the heel of one superpower or dominated by the other, unable to make large-scale international political decisions without implicating itself in the larger conflict. The rivalries that had divided the former “great powers” in the past seemed insignificant compared to the threat of a single overwhelming war initiated by foreign powers that could result in the end of history.

The USSR During the Cold War

Stalin died in 1954, leaving behind a country that was still comparatively poor, but enormously powerful. In addition, Stalin left a legacy of death and imprisonment that touched nearly every family in the USSR, with millions still trapped in the gulags of Siberia. After a power struggle between the top members of the communist party, Stalin’s successor emerged: Nikita Khrushchev, a former coal miner and engineer who rose in the ranks of the party to become its leader. Khrushchev was a “true believer” in the Soviet system, genuinely believing that the USSR would overtake the west economically and that its citizens would in turn eventually enjoy much better standards of living than those experienced in the west.

Khrushchev broke with Stalinism soon after securing power. In 1956, he gave a speech to the leaders of the communist party later dubbed the “secret speech” – it was not broadcast to the general public, but Khrushchev allowed it to leak to the state-controlled press. In it, Khrushchev blamed Stalin for bringing about a “cult of personality” that was at variance with true communist principles, and for “excesses,” a thinly veiled acknowledgement of the Siberian prison camps and summary executions. Shortly after the speech, Khrushchev had four million prisoners released from the gulags as a practical gesture demonstrating his sincerity. This period is called “The Thaw” in Soviet history. For a brief period, there was another flowering of literary and artistic experimentation comparable to that of the early 1920s. The ubiquitous censorship was relaxed, with a few accurate accounts of the gulags making it into mainstream publication. In turn, among many, there were genuine hopes for larger political reforms of the system.

This hope of a new beginning was not limited to the Soviet Union itself. In October of 1956, a reformist faction of the Hungarian communist party inspired a mass uprising calling for not just a reformed, more humanistic communism, but the expulsion of Soviet forces and “advisers” completely. That led to a full-scale invasion by the Soviet army that killed several thousand protesters in violent clashes (primarily in the capital city of Budapest), followed by the arrests of over half a million people in the aftermath. It was clear that Khrushchev might not want to follow directly in Stalin’s footsteps, but he had no intention of allowing genuine independence in the Soviet Bloc countries of Eastern Europe.

Angered both by the events in Hungary and by the growth of outright dissent with the Soviet system in the USSR itself, Khrushchev reasserted control. A few noteworthy works of art that hinted at dissent were allowed to trickle out (until Khrushchev was ousted by hardliners in 1964, at any rate), but larger-scale change was out of the question. The state instead concentrated on wildly ambitious – sometimes astonishingly impractical – economic projects. Soviet engineers and planners drained whole river systems to irrigate fields, Soviet factories churned out thousands of tons of products and materials no one wanted, and whole regions were polluted to the point of becoming nearly uninhabitable. Over time, cynicism replaced terror as the default outlook of Soviet citizens. It was no longer as dangerous to be alive as it had been under Stalin, but people recognized that the system was not “really” about the pursuit of communism. Instead, for most, the only hope of achieving a decent standard of living and relative personal stability was forming the right connections within the enormous party bureaucracy. The USSR went from a murderous police state under Stalin to a bloated, corrupt police state under Khrushchev and the leaders who followed him.

It was also under Khrushchev that the Cold War reached its most frenzied pitch. Khrushchev himself was an explosive personality who sincerely believed in the possibility of the USSR “winning” the Cold War by outstripping the western world economically and winning over the nations of the Third World to communism politically. To that end, he continued the Stalinist focus on building up heavy industry and, especially, military hardware, but he also devoted huge energies toward science and engineering.

During Khrushchev’s tenure as premier the “space race” joined the arms race as a major centerpiece of Cold War policy. Despite the limited practical consequences of some aspects of the space race, it was symbolically important to both sides – it was a very visible demonstration of scientific superiority, and the first superpower to reach a given breakthrough in the space race had thus “won” a major symbolic victory in the eyes of the world. In addition, since the space race was based on the mastery of rocket technology, the military implications were obvious. In 1957, the Soviets launched Sputnik, the first satellite to orbit the earth, an event which was perceived as a major Soviet triumph in the Cold War. Khrushchev claimed that the USSR had also developed missiles that could strike targets on the other side of the world, and thus the west feared that the Soviets could as easily detonate a nuclear weapon in the US as in Europe.

The resulting fear and resentment between the two sides saw even greater emphasis on both the space race and the buildup of nuclear arms going into the 1960s. The American President John F Kennedy was a hard-line anti-communist, a “cold warrior,” and he believed it was important to stand up to the Soviets symbolically and, if necessary, militarily. In 1959, Cuban revolutionaries overthrew the right-wing dictator Fulgencio Batista (who had been an American ally), and fearing American intervention, eventually aligned themselves with the USSR. Thus, as Kennedy took office in 1960, he faced not only the growing technological and military power of the USSR itself, but what he regarded as a Soviet puppet on the very doorstep of US territory.

In 1962, the US Central Intelligence Agency staged an unsuccessful attempt to overthrow the Cuban communist leader Fidel Castro, an event known as the Bay of Pigs Invasion. In the aftermath, Castro and Khrushchev agreed to install missile batteries in Cuba both as a deterrent against a potential invasion by the US in the future and to redress the superiority of American missile deployments. Khrushchev was eager to establish a military presence in the western hemisphere, especially since the US had already installed missile batteries in its allied nations of Italy and Turkey within striking distance of the USSR. American spy planes, however, detected the construction of the missile site in Cuba and the shipments of missiles en route to Cuba, leading to the point in history when the human race stood closest to complete extinction: the Cuban Missile Crisis.

When the US government learned of the Soviet missiles, there was serious consideration of launching a full-scale assault on Cuba, something that could have led directly to nuclear war. Many American military leaders believed at the time in the possibility of a “limited nuclear war” in which missile sites would be destroyed quickly enough to prevent the Soviets from launching counter-strikes. Instead, however, Kennedy and Khrushchev carefully engaged in behind-the-scenes diplomacy, both of them realizing the stakes of the conflict and, thankfully for world history, not wanting to destroy the world in the name of national pride. The American and Soviet navies faced off in the Atlantic while frenzied diplomacy sought an end to the crisis. After thirteen panicked days, both sides agreed to withdraw their missiles, but not before an incident in which a Soviet submarine very nearly launched nuclear torpedoes at an American ship. A single Soviet officer – Vasili Arkhipov – called off the strike that could have led directly to nuclear war.

In the aftermath of the Cuban Missile Crisis, the US and USSR agreed to create a “hotline” to ensure rapid communication in the event of future crises. The United States dropped the very idea of “limited” nuclear war from its tactical repertoire and instead recognized that any nuclear strike was the equivalent of “M.A.D.” (Mutually Assured Destruction). While the arms race between the superpowers continued, spiking again during the 1980s, both sides did enter into various treaties that limited the pace of nuclear arms production as well.

In 1964, having lost the confidence of key members of the Politburo, Khrushchev was forced out of office. He was replaced by Leonid Brezhnev, a lifelong communist bureaucrat. Brezhnev would hold power until 1982, overseeing a long period of what is usually characterized as stagnation by historians: the Soviet system, including its nominal adherence to Marxism-Leninism, would remain in place, but even elites abandoned the idea that “real” communism was achievable. Instead, life in the USSR was about trying to find a place in the system, rather than pursuing the more far-reaching goals of communist theory. The state and the economy – deeply wedded in any case – were rife with corruption and nepotism, and a deep-seated, bitter cynicism became the outlook of most Soviet citizens toward their government and their lot in life. Arguably, this pattern had already emerged under Khrushchev, but it truly came of age under Brezhnev.

During Brezhnev’s tenure as the Soviet premier, another eastern bloc nation tried unsuccessfully to break away from Soviet domination: Czechoslovakia. In the Spring of 1968, the Czech communist leader Alexander Dubcek (who had fought against the Nazis in the war and had been a staunch ally and trusted underling of the Soviets up to that point) received permission from Moscow to experiment with limited reforms. He called for “socialism with a human face,” meaning a kind of communist government that allowed freedom of speech, a liberalized outlook on human expression, and a diversified economy that could address sectors besides heavy industry. Dubcek relaxed censorship and allowed workers to organize into Soviets (councils) as they had in the early years of communist revolution in Russia. These reforms were eagerly embraced by the Czechs and Slovaks.

Predictably, the reforms proved too radical for Moscow. Brezhnev sent in the Soviet military, and all of the other Warsaw Pact countries (except Romania) also sent in troops. This reaction was regarded around the world as especially crude and disproportionate, given that the Czechs and Slovaks did not rise up in any kind of violent way (as the Hungarians had done, at least briefly, twelve years earlier). Instead, the message was clear: no meaningful reform would be possible in the East unless the leadership in Moscow somehow underwent a fundamental change of outlook. That change did eventually come, but not until the 1980s under Mikhail Gorbachev.

Conclusion: What Went Wrong with the USSR

In historical hindsight, the paradox of a “communist” country that so profoundly failed to realize its stated goals of freedom, equality, and justice, has led many people (not just historians) to speculate about what was inherently flawed with the Soviet system. There are many theories, three of which are considered below.

One idea is that the Soviet state was trapped in impossible circumstances. It was largely cut off from the aid of the rest of the world until after World War II, and the Bolsheviks inherited control of a backwards, economically-underdeveloped nation. They did their best, however brutal their methods, to catch up with the nations of the west and to create at least the possibility of a better life for future Soviet citizens. This thesis is supported by the success of the Red Army: if Stalin had not industrialized Russia and the Ukraine by force, the theory goes, the results of World War II would have been even more awful.

Another take is that communism is somehow contrary to human nature and thus doomed to failure, no matter what the circumstances or context. Here, scholars note the incredible prevalence of corruption at every level of Soviet society: the huge black market and the nepotism and infighting present in everything from getting a job to getting an apartment in one of the major cities. Greed proved an implacable foe to communist social organization, with the party apparatchiks reaping the benefits of their positions – better food, better housing, vacations – that were never available to rank-and-file citizens.

A more subtle and sympathetic interpretation is that some kind of communism might be possible (social democracies have thrived in Europe for decades, after all), but the Soviet system went mad with trying to control everything. The Soviet economy was the ultimate expression of the idea of a command economy, with every product produced according to arcane quotas set by huge bureaucracies within the Soviet state, and every industry was beholden to equally unrealistic quotas. The most elementary laws of supply and demand in economics were ignored in favor of irrational, and indeed arbitrary, systems of production. The results were chronic shortages of goods and services people actually needed (or wanted) and equally vast surpluses of useless, shoddy junk, from ill-fitting shoes to unreliable machinery. To cite a single example (noted by the historian Tony Judt), party leaders in the Soviet republic of Kyrgyzstan told farmers to buy up grain supplies from stores in order to meet their yearly quotas; those quotas were utterly impossible to meet through actual farming.

All of these ideas have something to them. It should also be considered that there had never been anything like a democratic or liberal society in Russia. There was no tradition of what the British called the “loyal opposition” of political parties who may disagree on particulars but who are still accepted as legitimate expressions of the will and opinion of parts of the citizenry. There were no “checks and balances” to hold back corruption either, and by the Brezhnev era political connections were far more important than was any kind of heartfelt devotion to Marxist theory. Thus, the kinds of decisions made by the Soviet leadership were inspired by a pure, ruthless will to see results against a backdrop of staggering inefficiency and corruption.

In the end, perhaps the biggest problem with the Soviet system was the fact that it was more important to fit into the system than to speak the truth. The essential threat of violence and imprisonment during the Stalinist period cast a long shadow on the rest of Soviet history. Conformity, ideological dogmatism, and indifference to any notion of fairness were all synonymous with “success” in Soviet society. Before long, competence and honesty were

threats to too many people already in power to be allowed to exist – as an example, famous Russian scientists lived under house arrest for decades because they could not be disposed of, but neither could they be allowed to state their views openly.

It also bears consideration that not everything about Soviet society was, actually, a failure. After the “Thaw” in the early 1950s, almost no one was executed for simply disagreeing with the state, and prison terms were much shorter. Standards of living were mediocre, but medical care, housing, and food was either free or cheap because of state subsidies. The kind of “leveling-out” associated with communist theory did happen, in a sense, because most people lived at a similar standard of living, the perks allowed to senior members of the communist party notwithstanding. In the end, the Soviet Union represented one of the most profound, albeit often blood-soaked and inhumane, political experiments in world history.

Image Citations (Wikimedia Commons):

Stalin – Public Domain

Five Year Plan Propaganda – Public Domain

Big Three – Public Domain

Supply Plane – Public Domain

Sputnik Stamp – Public Domain