Chapter 13: Postwar Conflict

One of the definitive transformations in global politics after World War II was the shift in the locus of power from Europe to the United States and the Soviet Union. It was American aid or Soviet power that guided the reconstruction of Europe after the war, and both superpowers proved themselves more than capable of making policy decisions for the countries within their respective spheres of influence. The Soviets directly controlled Eastern Europe and had an enormous amount of influence in the other communist countries, while the United States exercised considerable influence on the member nations of NATO.

Thus, many Europeans struggled to make sense of their own identity, with the height of European power still being a living memory. One issue of tremendous importance to most Europeans was the status of their colonies, most of which were still intact in the immediate postwar period. Many Europeans felt that, with all their flaws, colonies still somehow proved the relevance and importance of the mother countries – as an example, the former British prime minister Winston Churchill was dismayed by the prospect of Indian independence from the British commonwealth even when most Britons accepted it as inevitable. Many in France and Britain in particular thought that their colonies could somehow keep them on the same level as the superpowers in terms of global power and, in a sense, relevance.

There were a host of problems with imperialism by 1945, however, that were all too evident. Colonial troops had played vital roles in the war, with millions of Africans and Asians serving in the allied armies (well over two million troops from India alone served as part of the British military). Colonial troops fought in the name of defending democracy from fascism and tyranny, yet back in their home countries they did not have access to democratic rights. Many independence movements, such as India’s, refused to aid in the war effort as a result. Once the war was over, troops returned home to societies that were still governed not only as political dependencies, but were divided starkly along racial lines. The contrast between the ostensible goals of the war and the obvious injustice in the colonies could not have been more evident.

Simultaneously, the Cold War became the overarching framework of conflict around the world, sometimes playing a primary role in domestic conflicts in countries hundreds or even thousands of miles from either of the superpowers themselves. At its worst, the Cold War led to “proxy wars” between American-led or at least American-supplied anti-communists and communist insurgents inspired by, and occasionally supported by the Soviet Union or communist (as of 1949) China. There was thus a complex matrix of conflict around the world that combined independence struggles within colonies on the one hand and proxy conflicts and wars between factions caught in the web of the Cold War on the other. Sometimes, independence movements like those of India and Ghana managed to avoid being ensnared in the Cold War. Other times, however, countries like Vietnam became battlegrounds on which the conflict between capitalism and communism erupted in enormous bloodshed.

The newly-founded United Nations generally failed to prevent the outbreak of war despite its nominal goal of arbitrating peaceful solutions for international problems. It was hamstrung by the fact that the two superpowers were among those with permanent seats on the UN Security Council, the body that was charged with authorizing the use of force when necessary. Likewise, the two “camps” of the Cold War generally remained loyal to their respective superpower leaders, ensuring that there could be no unified decision making when it came to Cold War conflicts.

In addition, while some independence movements that avoided becoming embroiled in the Cold War were able to secure national independence peacefully, others did not. In many cases, European imperial powers reacted violently to their colonial subjects’ demands for independent governance, leading both the bloodshed and grotesque violations of human rights. Here, again, the United Nations was generally unable to prevent violence, although it did at times at least provide an ethical framework by which the actions of the imperialist powers might be judged historically.

Major Cold War Conflicts

Fortunately for the human species, the Cold War never turned into a “hot” war between the two superpowers, despite close calls like that of the Cuban Missile Crisis. It did, however, lead to wars around the world that were part of the Cold War setting but also involved conflicts between colonizers and the colonized. In other words, many conflicts in the postwar era represented a combination of battles for independence from European empires and proxy wars between the two camps of the Cold War.

The first such war was in Korea. Korea had been occupied by Japan since 1910, one of the first countries to be conquered during Japan’s bid to create an East Asian and Pacific empire that culminated in the Pacific theater of World War II. After the defeat of Japan, Korea was occupied by Soviet troops in the north and US troops in the south. In the midst of the confusion in the immediate postwar era, the two superpowers ignored Korean demands for independence and instead divided the country in two. In 1950, North Korean troops supported with Soviet arms and allied Chinese troops invaded the south in the name of reuniting the country under communist rule. This was a case in which both the Soviets and the Chinese directly supported an invasion in the name of spreading communism, something that would become far less common in subsequent conflicts. A United Nations force consisting mostly of American soldiers, sailors, and pilots fought alongside South Korean troops against the North Korean and Chinese forces.

Meanwhile, in 1945 Vietnamese insurgents declared Vietnam’s independence from France, and French forces (such as they were following the German occupation) hastily invaded in an attempt to hold on to the French colony of Indochina. When the Korean War exploded a few years later, the United States intervened to support France, convinced by the events in Korea that communism was spreading like a virus across Asia. As American involvement grew, orders for munitions and equipment from the US to Japan revitalized the Japanese economy and, ironically given the carnage of the Pacific theater of World War II, began to forge a strong political alliance between the two former enemies.

After three years of bloody fighting, including the invasion of a full-scale Chinese army in support of the northern forces, the Korean War ended in a stalemate. A demilitarized zone was established between North and South Korea in 1953, and both sides agreed to a cease fire. Technically, however, the war has never officially ended – both sides have simply remained in a tense state of truce since 1953. The war itself tore apart the country, with three million casualties (including 140,000 American casualties), and a stark ideological and economic divide between north and south that only grew stronger in the ensuing decades. As South Korea evolved to become a modern, technologically advanced and politically democratic society, the north devolved into a nominally “communist” tyranny in which poverty and even outright famine were tragic realities of life.

The Korean War energized the American obsession with preventing the spread of communism. President Truman of the US insisted, against the bitter protests of the British and French, that West Germany be allowed to rearm in order to help bolster the anti-Soviet alliance. As French forces suffered growing defeats in Indochina, the US ramped up its commitment in order to prevent another Asian nation from becoming a communist state. The American theory of the “domino effect” of the spread of communism from country to country seemed entirely plausible at the time, and across the American political spectrum there was a strong consensus that communism could only be held in check by the application of military force.

That obsession led directly to the Vietnam War (known in Vietnam as the American War). The Vietnam War is among the most infamous in modern American history (for Americans) because America lost it. In turn, American commitment to the war only makes if it is placed in its historical context, that of a Cold War conflict that appeared to American policymakers as a test of resolve in the face of the spread of communism. The conflict was, in fact, as much about colonialism and imperialism as it was communism: the essential motivation of the North Vietnamese forces was the desire to seize genuine independence from foreign powers. The war itself was an outgrowth of the conflict between the Vietnamese and their French colonial masters, one that eventually dragged in the United States.

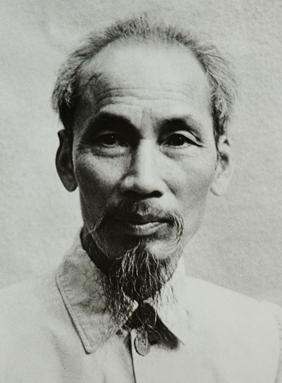

The war “really” began with the end of World War II. During the war, the Japanese seized Vietnam from the French, but with the Japanese defeat the French tried to reassert control, putting a puppet emperor on the throne and moving their forces back into the country. Vietnamese independence leaders, principally the former Parisian college student (and former dishwasher – he worked at restaurants in Paris while a student) Ho Chi Minh, led the communist North Vietnamese forces (the Viet Minh) in a vicious guerrilla war against the beleaguered French. In a prescient moment with a French official, Ho Chi Minh once prophesied that “you will kill ten of our men, but we will kill one of yours and you will end up by wearing yourselves out.” The Soviet Union and China both provided weapons and aid to the North Vietnamese, while the US anticipated its own (later) invasion by supporting the South.

The French period of the conflict reached its culminating point in 1954 when the French were soundly defeated at Dien Bien Phu, a French fortress that was overwhelmed by the Viet Minh. The French retreated, leaving Vietnam torn between the communists in the north and a corrupt but anti-communist force in the south supported by the United States. Refusing to allow the national elections that had been planned for 1956, the US instead propped up an unpopular president, Ngo Dinh Diem, who claimed authority over the entire country. An insurgency, labeled the Viet Cong (“Vietnamese communists”) by the Diem government, supported by the north erupted in 1958, leading the US to provision hundreds of millions of dollars in aid and, soon, an increasing number of military advisers to the south.

In 1964, pressured by both Soviet and Chinese advisers and with the US stepping up pressure on the Viet Cong, the Viet Minh leadership launched a full-scale invasion in the name of Vietnamese unification. American involvement skyrocketed as the South Vietnamese proved unable to contain the Viet Minh and the Viet Cong insurgents. Over time, thousands of American military “advisers,” mostly made up of what would become known as special forces, were joined by hundreds of thousands of American troops. In 1964, citing a fabricated attack on an American ship in the Gulf of Tonkin, President Lyndon Johnson called for a full-scale armed response, which opened the floodgates for a true commitment to the war (technically, war was never declared, however, with the entire conflict constituting a “police action” from the American policy perspective).

Ultimately, Ho Chi Minh was proven right in his predictions about the war. American and South Vietnamese forces were fought to a standstill by the Viet Minh and Viet Cong, with neither side winning a definitive victory. All the while, however, the war was becoming more and more unpopular in America itself and in its allied countries. As the years went by, journalists catalogued much of the horrific carnage unleashed by American forces, with jungles leveled by chemical agents and napalm and, notoriously, civilians massacred. The United States resorted to a lottery system tied to conscription – “the draft” – in 1969, which led to tens of thousands of American soldiers sent against their will to fight in jungles thousands of miles from home. Despite the vast military commitment, US and South Korean forces started to lose ground by 1970.

The entire youth movement of the 1960s and 1970s was deeply embedded in the anti-war stance caused by the mendacious press campaigns about the war carried on by the US government, by atrocities committed against Vietnamese civilians, and by the deep unpopularity of the draft. In 1973, with American approval for the war hovering at 30%, President Richard Nixon oversaw the withdrawal of American troops and the end of support for the South Vietnamese. The Viet Minh finally seized the capital of Saigon and ended the war in 1975. The human cost was immense: over a million Vietnamese died, along with some 60,000 American troops.

In historical hindsight, one of the striking aspects of the Vietnam War was the relative restraint of the Soviet Union. The USSR provided both military supplies and financial aid to North Vietnamese forces, but it fell far short of any kind of sustained intervention along the American model in the south. Likewise, the People’s Republic of China supported the Viet Minh, but it did so in direct competition with the USSR (following a historic break between the two countries in 1956). Nevertheless, whereas the US regarded Vietnam as a crucial bulwark against the spread of communism, and subsequently engaged in a full-scale war as a result, the USSR remained circumspect, focusing on maintaining power and control in the eastern bloc and avoiding direct military commitment in Vietnam.

That being noted, not all Cold War conflicts were so lopsided in terms of superpower involvement. As described in the last chapter, Cuba was caught at the center of the single most dangerous nuclear standoff in history in part because the USSR was willing to confront American interests directly. Something comparable occurred across the world in Egypt even earlier, representing another case of an independence movement that became embedded in Cold War politics. There, unlike in Vietnam, both superpowers played a major role in determining the future of a nation emerging from imperial control, although (fortunately) neither committed itself to a war in doing so.

Egypt had been part of the British empire since 1882 when it was seized during the Scramble for Africa. It achieved a degree of independence after World War I, but remained squarely under British control in terms of its foreign policy. Likewise, the Suez Canal – the crucially important link between the Mediterranean and Red Sea completed in 1869 – was under the direct control of a Canal Company dominated by the British and French. In 1952 the Egyptian general Gamal Abdel Nasser overthrew the British-supported regime and asserted complete Egyptian independence. The United States initially sought to bring him into the American camp by offering funds for a massive new dam on the Nile, but then Nasser made an arms deal with (communist) Czechoslovakia. The funds were denied, and Nasser announced that he would instead seize the Suez Canal (which flowed directly through Egyptian territory) to pay for the dam instead.

Thus, in the summer of 1956 Nasser nationalized the Suez Canal. Henceforth, all of the traffic going through the vitally important canal would be regulated by Egypt directly. Stung by the nationalization, Britain and France plotted to reassert control. The British and French were joined by Israeli politicians who saw Nasser’s bold move as a direct threat to Israeli security (sharing as they did an important border). A few months of frenzied behind-the-scenes diplomacy and planning ensued, and in October Israeli, British, and French forces invaded Egypt.

Despite being a legacy of imperialism, the “Suez Crisis” swiftly became a Cold War conflict as well. Concerned both at the imperial posturing of Britain and France and at the prospect of the invasion sparking Soviet involvement, US President Dwight Eisenhower forcefully demanded that the Israelis, French, and British withdraw, threatening economic boycotts (all while attempting to reduce the volatility with the Soviets). Days later Khrushchev threatened nuclear strikes if the French, Israeli, and British forces did not pull back. Cowed, the Israeli, French, and British forces retreated. The Suez Crisis demonstrated that the US dominated the policy decisions of its allies almost as completely as did the Soviets theirs. The US might not run its allied governments as puppet states, but it could directly shape their foreign policy.

In the aftermath of the Suez Crisis, Egypt’s control of the canal was assured. While generally closer to the USSR than the US in its foreign policy, it also tried to initiate a genuine “third way” between the two superpowers, and Egyptian leaders called for Arab nationalism and unity in the Middle East as a way to stay independent of the Cold War. Despite that intention, however, the Suez Crisis saw both superpowers take a more active interest in maintaining client, or at least friendly, states in the region, regardless of the ideological commitments of those states. This led to the strange spectacle of the United States, nominal champion of democracy, forming a close alliance with the autocratic monarchy of Saudi Arabia and other states resolutely uncommitted to representative government or even basic human rights.

Independence Movements and Decolonization

Despite the enormous pressure exerted by the superpowers, some independence movements did manage to avoid becoming a proxy conflict within the Cold War. For the most part, the simplest way in which an independence movement might avoid superpower involvement was to steer clear of communist rhetoric or nationalized industries. From Asia to Latin America, independence movements and rebel groups that adopted communist ideology were targeted by the US, whereas those that avoided it rarely drew the ire of either superpower. The exceptions were countries like Iran that tried to nationalize domestic industries – the US sponsored a coup to overthrow the prime minister Mohammed Mosadeq in 1953 for trying to assert Iranian ownership of its own oil fields, replacing him with a corrupt king, Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, who was beholden to American interests. Still, in general it was possible for a country to fight for its independence and still stay in the good graces of the USSR (as with Egypt) without openly embracing communism, whereas it was impossible for a country to embrace socialism and stay out of the crosshairs of the US thanks to the Truman Doctrine, which committed the United States to armed intervention in the case of a communist-backed uprising.

Thus, while there were only a handful of true proxy wars over the course of the Cold War, there were dozens of successful movements of independence. As quickly as European empires had grown in the second half of the nineteenth century, they collapsed in the decades following World War II in a phenomenon known as decolonization. In the inverse of the Scramble for Africa, nearly the entire continent of Africa remained colonized by European powers as of World War II but nearly all of it was independent by the end of the 1960s. Likewise, European possessions in Asia all but vanished in the postwar era.

Given the rapidity with which the empires collapsed it is tempting to imagine that the European states simply acknowledged the moral bankruptcy of imperialism after World War II and peacefully relinquished their possessions. Instead, however, decolonization was often as bloody and inhumane as had been the establishment of empire in the first place. In some cases, such as Dutch control of Indonesia and French sovereignty in Indochina, European powers clung desperately to colonies in the name of retaining their geopolitical relevance. In others, such as the British in Kenya and the French in Algeria, large numbers of white settlers refused to be “abandoned” by the European metropole, leading to sometimes staggering levels of violence. That being noted, there were also major (soon to be former) colonies that achieved independence without the need for violent insurrection against their imperial masters. (Note: given the very large number of countries that achieved independence during the period of decolonization, this chapter concentrates on some of the particularly consequential cases in terms of their geopolitical impact at the time and since).

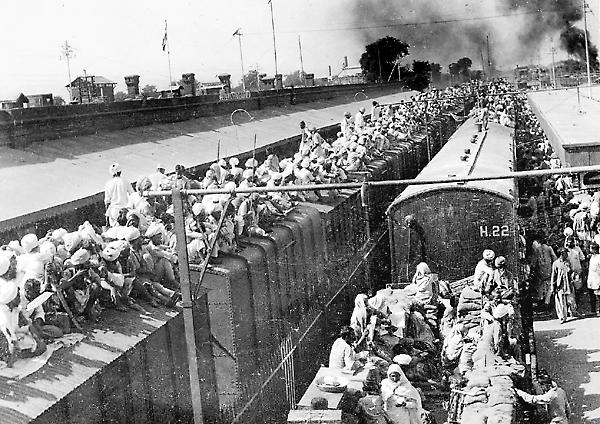

The case of India is iconic in that regard. Long the “jewel in the crown of the British empire,” India was both an economic powerhouse and a massive symbol of British prestige. By World War II, however, the Indian National Congress had agitated for independence for almost sixty years. An astonishing 2.5 million Indian troops served the British Empire during World War II despite the growth in nationalist sentiment, but returned after victory in Europe was achieved to find a social and political system still designed to keep Indians from positions of importance in the Indian administration. Peaceful protests before the war grew in intensity during it, and in the aftermath (in part because of the financial devastation of the war), a critical mass of British politicians finally conceded that India would have to be granted independence in the near future. The British state established the date of independence as July 18, 1947.

The British government, however, made it clear that the actual logistics of independence and of organizing a new government were to be left to the Indians. A conflict exploded between the Indian Muslim League and the Hindu-dominated Congress Party, with the former demanding an independent Muslim state. The British came to support the idea and finally the Congress Party conceded to it despite the vociferous resistance of the independence leader Mahatma Gandhi. When independence became a reality, India was divided between a non-contiguous Muslim state, Pakistan, and a majority-Hindu state, India.

This event is referred to as “The Partition.” Millions of Muslims were driven from India and millions of Hindus and Sikhs were driven from Pakistan, leading to countless acts of violence during the expulsion of both Muslims and Hindus from what had been their homes. Hundreds of thousands, and possibly more than a million people died, and the states of Pakistan and India remain at loggerheads to the present. Gandhi himself, who bitterly opposed the Partition, was murdered by a Hindu extremist in 1948.

Religious (and ethnic) divides within former colonies were not unique to India. Many countries that sought independence were products of imperialism in the first place – the “national” borders of states like Iraq, Ghana, and Rwanda had been arbitrarily created by the imperial powers decades earlier with complete disregard for the religious and ethnic differences of the people who lived within the borders. In the Iraqi example, both Sunni and Shia Muslims, Christian Arabs (the Assyrians, many of whom claim a direct line of descent from ancient Assyria), different Arab ethnicities, and Kurds all lived side-by-side. Its very existence was due to a hairbrained scheme by Winston Churchill, foreign secretary of the British governments after World War I, to lump together different oil-producing regions in one convenient state under British domination. Iraq’s ethnic and religious diversity did not guarantee violent conflict, of course, but when circumstances arose that inspired conflict, violence could, and often did, result.

The current ongoing crisis of Israel – Palestine is both a result of arbitrary borders drawn up by former imperial powers as well as a unique case of a nationalist movement achieving its goals for a ethnic-religious homeland. The British had held the “mandate” (political governorship) of the territory of Palestine before WWII, having seized it after the collapse of the Ottoman Empire. Thousands of European Jews had been immigrating to Palestine since around the turn of the century, fleeing anti-Semitism in Europe and hoping to create a Jewish state as part of the Zionist movement founded during the Dreyfus Affair in France.

During World War I, the British had both promised to support the creation of a Jewish homeland in Palestine while also assuring various Arab leaders that Britain would aid them in creating independent states in the aftermath of the Ottoman Empire’s expected demise. Even the official British declaration that offered support for a Jewish homeland – the Balfour Declaration of 1917 – specifically included language that promised the Arabs of Palestine (both Muslim and Christian) support in ensuring their own “civil and religious rights.” In other words, the dominant European power in the area at the time, and the one that was to directly rule it from 1920 – 1947, tried to appease both sides with vague assurances.

After World War I, however, the British established control over a large swath of territory that included the future state of Israel, frustrating Arab hopes for their own independence. Countries like Iraq, Transjordan, and the Nadj (forerunner to today’s Saudi Arabia) were simply invented by British politicians, often with compliant Arab leaders dropped onto newly-invented thrones in the process. Meanwhile, between 1918 and 1939, the Jewish population of Palestine went from roughly 60,000 to 650,000 as Jews attracted to Zionism moved to the area. The entire period was replete with riots and growing hostility between the Arab and Jewish populations, with the British trying (and generally failing) to keep the peace. As war loomed in 1939 the British even tried to restrict Jewish immigration to avoid alienating the region’s Arab majority.

After World War II, the British proved unable and unwilling to try to manage the volatile region, turning the territory over to the newly-created United Nations in April of 1947. The UN’s plan to divide the territory into two states – one for Arabs and one for Jews – was rejected by all of the countries in the region, and Israel’s creation as a formal state in May of 1948 saw nine months of war between the Jews of the newly-created state of Israel and a coalition of the surrounding Arab states: Egypt, Syria, Iraq, and Lebanon, along with small numbers of volunteers from other Arab countries. Israel consistently fielded larger, better-trained and better-equipped armies in the ensuing war, as the Arab states were in their infancy as well, and Jewish settlers in Palestine had spent years organizing their own militias. When the dust settled, there were nearly a million Palestinian refugees and a state that promised to be the center of conflict in the region for decades to come.

Since the creation of Israel, there have been three more full-scale regional wars: the 1956 Suez War (noted above in the discussion of Egypt), which had no lasting consequences besides adding fuel to future conflicts, the Six-Day War of 1967, that resulted in great territorial gains for Israel, and the Yom Kippur War of 1973 that undid some of those gains. In addition to the actual wars, there have been ongoing explosions of violence between Palestinians and Israelis that continue to the present.

Africa

While the cases of India and Israel were, and are, of tremendous geopolitical significance, the most striking case of decolonization at the time was the wave of independence movements across Africa in the 1950s and 1960s. Africa had been the main target of the European imperialism of the late nineteenth century. The Scramble for Africa was both astonishingly quick (lasting from the 1880s until about 1900) and amazingly complete, with all of Africa but Liberia and Ethiopia taken over by one European state or another. In the postwar era, almost every African country secured independence just as quickly; the whole edifice of European empire in Africa collapsed as rapidly as it had arisen a bit over a half century earlier. In turn, in some places this process was peaceful, but in many it was extremely violent.

In West Africa, the former colony of the Gold Coast became well known for its charismatic independence leader Kwame Nkrumah. Nkrumah not only successfully led Ghana to independence in 1957 after a peaceful independence movement and negotiations with the British, but founded a movement called Pan-Africanism in which, he hoped, the nations of Africa might join together in a “United States of Africa” that would achieve parity with the other great powers of the world to the betterment of Africans everywhere. His vision was of a united African league, possibly even a single nation, whose collective power, wealth, and influence would ensure that outside powers would never again dominate Africans. While that vision did not come to pass, the concept of pan-Africanism was still vitally important as an inspiration for other African independence movements at the time.

In Kenya, in contrast, hundreds of thousands of white colonists were not interested in independence from Britain. By 1952, a complex web of nationalist rebels, impoverished villagers and farmers, and counter-insurgent fighters plunged the country into a civil war. The British and native white Kenyans reacted to the uprising by creating concentration camps, imprisoning rebels and slowly starving them to death in the hills. The rebels, disparagingly referred to as “Mau Maus” (meaning something like “hill savages”), in turn, attacked white civilians, in many cases murdering them outright. Finally, after 11 years of war, Kenya was granted its independence and elected a former insurgent leader as its first president. Ironically, while British forces were in a dominant position militarily, the British state was financially over-extended. Thus, Britain granted Kenyan independence in 1963.

While most former colonies adopted official policies of racial equality, and for the first time since the Scramble black Africans achieved political power almost everywhere, there was one striking exception: South Africa. South Africa had always been an unusual British colony. 21% of the South African population was white, divided between the descendents of British settlers and the older Dutch colony of Afrikaners who had been conquered and then incorporated by the British at the end of the nineteenth century. The Afrikaners in particular were virulently racist and intransigent, unwilling to share power with the black majority. As early as 1950 white South Africans (British and Afrikaner alike) emphatically insisted on the continuation of a policy known as Apartheid: the legal separation of whites and blacks and the complete subordination of the latter to the former.

South Africa became independent from Britain in 1961, but Apartheid remained as the backbone of the South African legal system, systematically repressing and oppressing the majority black population. Even as overtly racist laws were repealed elsewhere – not least in the United States as a result of the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s – Apartheid remained resolutely intact. That system would remain in place until 1991, when the system finally collapsed and the long-imprisoned anti-Apartheid activist leader Nelson Mandela was released, soon becoming South Africa’s first black president.

British colonies were not alone in struggling to achieve independence, nor in the legacy of racial division that remained from the period of colonization. One of the most violent struggles for independence of the period of decolonization in Africa occurred in the French territory of Algeria. The struggles surrounding Algerian independence, which began in 1952, were among the bloodiest wars of decolonization. Hundreds of thousands of Algerians died, along with tens of thousands of French and

pieds-noires (“black feet,” the pejorative term invented by the French for the white residents of Algeria). The heart of the conflict had to do with a concept of French identity: particularly on the political right, many French citizens felt that France’s remaining colonies were vital to its status as an important geopolitical power. Likewise, many in France were ashamed of the French defeat and occupation in World War II and refused to simply give up France’s empire without a struggle. This sentiment was felt particularly acutely by the French officer corps, with many French officers having only ever been on the losing side of wars (World War II and Indochina). They were thus determined to hold on to Algeria at all costs.

On the other hand, many French citizens realized all too well that the values the Fourth French Republic supposedly stood for – liberty, equality, and fraternity – were precisely what had been denied the native people of Algeria since it was first conquered by France during the restored monarchy under the Bourbons in the early nineteenth century. In fact, “native” Algerians were divided legally along racial and religious lines: Muslim Arab and Berber Algerians were denied access to political power and usually worked in lower-paying jobs, while white, Catholic Algerians (descendents of both French and Italian settlers) were fully enfranchised French citizens. In 1954, a National Liberation Front (FLN) composed of Arab and Berber Algerians demanded independence from France and launched a campaign of attacks on both French officials and, soon,

pieds-noires civilians.

The French response was brutal. French troops, many fresh from the defeat in Indochina, responded to the National Liberation Front with complete disregard for human rights, the legal conduct of soldiers in relation to civilians, or concern for the guilt or innocence of those suspected of supporting the rebellion. Infamously, the army resorted almost immediately to a systematic campaign of torture against captured rebels and those suspected of having information that could aid the French. Algerian civilians were often caught in the middle of the fighting, with the French army targeting the civilian populace when it saw fit. While the torture campaign was kept out of the press, rumors of its prevalence soon spread to continental France, inspiring an enormous debate as to the necessity and value of holding on to Algeria. The war grew in Algeria even as France itself was increasingly torn apart by the conflict.

Within a few years, as the anti-war protest campaign grew in France itself, many soldiers both in Algeria and in other parts of France and French territories grew disgusted with what they regarded as the weak-kneed vacillation on the part of republican politicians. Those soldiers created ultra-rightist terrorist groups, launching attacks on prominent intellectuals who spoke out against the war (the most prominent French philosopher at the time, Jean-Paul Sartre, had his apartment in Paris destroyed in a bomb attack). Troops launched an attempted coup in Algeria in 1958 and briefly succeeded in seizing control of the French-held island of Corsica as well.

It was in this context of near-civil war, with the government of the Fourth Republic paralyzed and the prospect of a new right-wing military dictatorship all too real, that the leader of the Free French forces in World War II, Charles de Gaulle, volunteered to “rescue” France from its predicament, with the support of the army. He placated the army temporarily, but when it became clear he intended to pull France out of Algeria, a paramilitary terrorist group twice tried to assassinate him. De Gaulle narrowly survived the assassination attempts and forced through a new constitution that vested considerable new powers in the office of the president. De Gaulle opened negotiations with the FLN in 1960, leading to the ratification of Algerian independence in 1962 by a large majority of French voters. Despite being an ardent believer in the French need for “greatness,” De Gaulle was perceptive enough to know that the battle for Algeria was lost before it had begun.

In the aftermath of the Algerian War, millions of white Algerians moved to France, many of them feeling betrayed and embittered. They became the core of a new French political far-right, openly racist and opposed to immigration from France’s former colonies. Many members of that resurgent right wing coalesced in the first openly fascistic party in France since the end of World War II: the Front National. Racist, anti-Semitic, and obsessed with a notion of French identity embedded in the culture of the Vichy Regime (i.e. the French fascist puppet state under Nazi occupation), the National Front remains a powerful force in French politics to this day.

The Non-Aligned Movement and Immigration

In the context of the Cold War, many struggles over decolonization were tied closely to the attitudes and involvement of the US and USSR. Vietnam provides perhaps the most iconic example. What was “really” a struggle for independence became a global conflict because of the socialist ideology espoused by the Viet Minh nationalists. Many leaders of formerly-colonized countries, however, rejected the idea that they had to choose sides in the Cold War and instead sought a truly independent course. The dream of many political elites in countries in the process of emerging from colonial domination was that former colonies around the world, but especially those in Africa and Asia, might create a new “superpower” through their alliance. The result was the birth of the Nonaligned Movement.

The beginning of the Nonaligned Movement was the Bandung Conference of 1955. In the Indonesian city of Bandung, leaders from countries in Africa, Asia, and South America met to discuss the possibility of forming a coalition that might push back against superpower dominance. This was the high point of the Pan-Africanism championed by Kwame Nkrumah described above, and in turn non-aligned countries earnestly hoped that their collective strength could compensate for their individual weakness vis-à-vis the superpowers. A French journalist at the conference created the term “third world” to describe the bloc of nations: neither the first world of the US and western Europe, nor the second world of the USSR and its satellites, but the allied bloc of former colonies.

While the somewhat utopian goal of a truly united third world proved as elusive as a United States of Africa, the real, meaningful effect of the conference (and the continued meetings of the nonaligned movement) was at the United Nations. The Nonaligned Movement ended up with over 100 member nations, wielding considerable power in the General Assembly of the UN and successfully directing policies and aid money to poorer nations. During the crucial decades of decolonization itself, the Nonaligned Movement also served as inspiration for millions around the world who sought not only independence for its own sake, but in the name of creating a more peaceful and prosperous world for all.

The irony of decolonization is that even as former European colonies were achieving formal political independence, millions of former colonized peoples were flocking to Europe for work. A postwar economic boom in Europe (described in the next chapter) created a huge market for labor, especially in fields of unskilled labor. Thus, Africans, Caribbeans, Asians, and people from the Middle East from former colonies all came in droves to work at jobs Europeans did not want, because those jobs still paid more than even skilled work did in the former colonies.

Initially, most immigrant laborers were single men, “guest workers” in the parlance of the time, who were expected to work for a time, send money home, then return to their places of origin. By the mid-1960s, however, families followed, demographically transforming the formerly almost all-white Europe into a genuinely multi-ethnic society. For the first time, many European societies grew ethnically and racially diverse, and within a few decades, a whole generation of non-white people were native-born citizens of European countries.

The result was an ongoing struggle over national and cultural identity. Particularly in places like Britain, France, and postwar West Germany, the official stance of governments and most people alike was that European culture was colorblind, and that anyone who culturally assimilated could be a productive part of society. The problem was that it was far easier to maintain that attitude before many people not born in Europe made their homes there; as soon as significant minority populations became residents of European countries, there was an explosion of anti-immigrant racism among whites. In addition, in cases like France, former colonists who had fled to the metropole were often hardened racists who openly called for exclusionary practices and laws. Europeans were forced to grapple with the idea of cultural and racial diversity in a way that was entirely new to them (in contrast to countries like the United States, which has

always

been highly racially diverse following the European invasions of the early modern period).

One group of British Marxist scholars, many of whom were immigrants or the children of immigrants, described this phenomenon as “the empire strikes back”: having seized most of the world’s territory by force, Europeans were now left with a legacy of racial and cultural diversity that many of them did not want. In turn, the universalist aspirations of “Western Civilization” were challenged as never before.

Image Citations (Wikimedia Commons):

Korean Refugees – Public Domain

Ho Chi Minh – Public Domain

Napalm Attack – Fair Use, Nick Ut / Associated Press

Partition – Public Domain

Algerian War Soldiers – Public Domain