Chapter 3: The Bronze Age and The Iron Age

The Bronze Age is a term used to describe a period in the ancient world from about 3000 BCE to 1100 BCE. That period saw the emergence and evolution of increasingly sophisticated ancient states, some of which evolved into real empires. It was a period in which long-distance trade networks and diplomatic exchanges between states became permanent aspects of political, economic, and cultural life in the eastern Mediterranean region. It was, in short, the period during which civilization itself spread and prospered across the area.

The period is named after one of its key technological bases: the crafting of bronze. Bronze is an alloy of tin and copper. An alloy is a combination of metals created when the metals bond at the molecular level to create a new material entirely. Needless to say, historical peoples had no idea why, when they took tin and copper, heated them up, and beat them together on an anvil they created something much harder and more durable than either of their starting metals. Some innovative smith did figure it out, and in the process ushered in an array of new possibilities.

Bronze was important because it revolutionized warfare and, to a lesser extent, agriculture. The harder the metal, the deadlier the weapons created from it and the more effective the tools. Agriculturally, bronze plows allowed greater crop yields. Militarily, bronze weapons completely shifted the balance of power in warfare; an army equipped with bronze spear and arrowheads and bronze armor was much more effective than one wielding wooden, copper, or obsidian implements.

An example of bronze’s impact is, as noted in the previous chapter, the expansionism of the New Kingdom. The New Kingdom of Egypt conquered more territory than any earlier Egyptian empire. It was able to do this in part because of its mastery of bronze-making and the effectiveness of its armies as a result. The New Kingdom also demonstrates another noteworthy aspect of bronze: it was expensive to make and expensive to distribute to soldiers, meaning that only the larger and richer empires could afford it on a large scale. Bronze tended to stack the odds in conflicts against smaller city-states and kingdoms, because it was harder for them to afford to field whole armies outfitted with bronze weapons. Ultimately, the power of bronze contributed to the creation of a whole series of powerful empires in North Africa and the Middle East, all of which were linked together by diplomacy, trade, and (at times) war.

The Bronze Age States

There were four major regions along the shores of, or near to, the eastern Mediterranean that hosted the major states of the Bronze Age: Greece, Anatolia, Canaan and Mesopotamia, and Egypt. Those regions were close enough to one another (e.g. it is roughly 800 miles from Greece to Mesopotamia, the furthest distance between any of the regions) that ongoing long-distance trade was possible. While wars were relatively frequent, most interactions between the states and cultures of the time were peaceful, revolving around trade and diplomacy. Each state, large and small, oversaw diplomatic exchanges written in Akkadian (the international language of the time) maintaining relations, offering gifts, and demanding concessions as circumstances dictated. Although the details are often difficult to establish, we can assume that at least some immigration occurred as well.

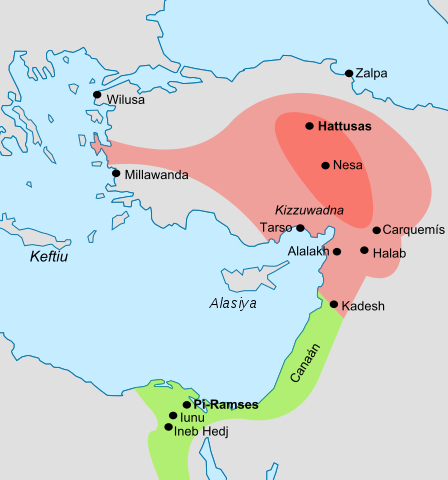

One state whose very existence coincided with the Bronze Age, vanishing afterwards, was that of the Hittites. Beginning in approximately 1700 BCE, the Hittites established a large empire in Anatolia, the landmass that comprises present-day Turkey. The Hittite Empire expanded rapidly based on a flourishing bronze-age economy, expanding from Anatolia to conquer territory in Mesopotamia, Syria, and Canaan, ultimately clashing with the New Kingdom of Egypt. The Hittites fought themselves to a stalemate against the Egyptians, after which they reached a diplomatic accord to hold on to Syria while the Egyptians held Canaan.

Unlike the Egyptians, the Hittites had the practice of adopting the customs, technologies, and religions of the people they conquered and the people they came in contact with. They did not seek to impose their own customs on others, instead gathering the literature, stories, and beliefs of their subjects. Their pantheon of gods grew every time they conquered a new city-state or tribe, and they translated various tales and legends into their own language. There is some evidence that it was the Hittites who formed the crucial link between the civilizations of Mesopotamia and the civilizations of the Mediterranean, most importantly of the Greeks. The Hittites transmitted Mesopotamian technologies (including math, astronomy, and engineering) as well as Mesopotamian legends like the Epic of Gilgamesh, the latter of which may have gone through a long process of translation and re-interpretation to become the Greek story of Hercules. Simply put, the Hittites were the quintessential Bronze Age civilization: militarily powerful, economically prosperous, and connected through diplomacy and war with the other cultures and states of the time.

The Hittite state is depicted in pink and New Kingdom Egyptian territory in green on the map above. The island “Alasiya” is present-day Cyprus in the eastern Mediterranean.

To the east of the Hittite Empire, Mesopotamia was not ruled by a single state or empire during most of the Bronze Age. The Babylonian empire founded by Hammurabi was overthrown by the Kassites (whose origins are unknown) in 1595 BCE, the conquest following a Hittite invasion that sacked Babylon but did not stay to rule over it. Over the following centuries, the Kassites successfully ruled over Babylon and the surrounding territories, with the entire region enjoying a period of prosperity. To the north, beyond Mesopotamia (the land between the rivers) itself, a rival state known as Assyria both traded with and warred against Kassite-controlled Babylon. Eventually (starting in 1225 BCE), Assyria led a short-lived period of conquest that conquered Babylon and the Kassites, going on to rule over a united Mesopotamia before being forced to retreat against the backdrop of a wider collapse of the political and commercial network of the Bronze Age (described below).

Both the Kassites and the Assyrians were proud members of the diplomatic network of rulers that included New Kingdom Egypt and the Hittites (as well as smaller and less significant kingdoms in Canaan and Anatolia). Likewise, both states encouraged trade, and goods were exchanged across the entire region of the Middle East. Compared to some later periods, it was a time of relative stability and, while sometimes interrupted by short-term wars, mostly peaceful relations between the different states.

To the west, it was during the Bronze Age that the first distinctly Greek civilizations arose: the Minoans of the island of Crete and the Mycenaeans of Greece itself. Their civilizations, which likely merged together due to invasion after a long period of coexistence, were the basis of later Greek civilization and thus a profound influence on many of the neighboring civilizations of the Middle East in the centuries to come, just as the civilizations of the Middle East unquestionably influenced them. At the time, however, the Minoans and Mycenaeans were primarily traders and, in the case of the Mycenaeans, raiders, rather than representing states on par with those of the Hittites, Assyrians, or Egyptians.

Both the Minoans and Mycenaeans were seafarers. Whereas almost all of the other civilizations of the eastern Mediterranean were land empires, albeit ones who traded and traveled via waterways, the Greek civilizations were very closely tied to the sea itself. The Minoans ruled the island of Crete in the Mediterranean and created a merchant marine (i.e. a fleet whose purpose is primarily trade, not war) to trade with the Egyptians, Hittites, and other peoples of the area. One of the noteworthy archaeological traits of the Minoans is that there is very little evidence of fortifications of their palaces or cities, unlike those of other ancient peoples, indicating that they were much less concerned about foreign invasion than were the neighboring land empires thanks to the Minoans’ island setting.

The Minoans built enormous palace complexes that combined government, spiritual, and commercial centers in huge, sprawling areas of building that were interconnected and which housed thousands of people. The Greek legend of the labyrinth, the great maze in which a bull-headed monster called the minotaur roamed, was probably based on the size and the confusion of these Minoan complexes. Frescoes painted on the walls of the palaces depicted elaborate athletic events featuring naked men leaping over charging bulls. Minoan frescoes have even been found in the ruins of an Egyptian (New Kingdom) palace, indicating that Minoan art was valued outside of Crete itself.

The Minoans traded actively with their neighbors and developed their own systems of bureaucracy and writing. They used a form of writing referred to by historians as Linear A that has never been deciphered. Their civilization was very rich and powerful by about 1700 BCE and it continued to prosper for centuries. Starting in the early 1400s BCE, however, a wave of invasions carried out by the Mycenaeans to the north eventually extinguished Minoan independence. By that time, the Minoans had already shared artistic techniques, trade, and their writing system with the Mycenaeans, the latter of which served as the basis of Mycenaean record keeping in a form referred to as Linear B. Thus, while the Minoans lost their political independence, Bronze-Age Greek culture as a whole became a blend of Minoan and Mycenaean influences.

The Minoans were, according to the surviving archaeological evidence, relatively peaceful. They traded with their neighbors, and while there is evidence of violence (including human sacrifice) within Minoan society, there is no indication of large-scale warfare, just passing references from the Mycenaeans about Minoan mastery of the seas. In contrast, the Mycenaeans were extremely warlike. They traded with their neighbors but they also plundered them when the opportunity arose. Centuries later, the culture of the Mycenaeans would be celebrated in the epic poems (nominally written by the poet Homer, although it is likely “Homer” is a mythical figure himself) The Iliad and The Odyssey, describing the exploits of great Mycenaeans heroes like Agamemnon, Achilles, and Odysseus. Those exploits almost always revolved around warfare, immortalized in Homer’s account of the Mycenaean siege of Troy, a city in western Anatolia whose ruins were discovered in the late nineteenth century CE.

From their ships, the Mycenaeans operated as both trading partners and raiders as circumstances would dictate; it is clear from the archeological evidence that they traded with Egypt and the Near East (i.e. Lebanon and Palestine), but equally clear that they raided and warred against both vulnerable foreign territories and against one another. There is even evidence that the Hittites enacted the world’s first embargo of shipping and goods against the Mycenaeans in retaliation for Mycenaean meddling in Hittite affairs.

The Mycenaeans relied on the sea so heavily because Greece was a very difficult place to live. Unlike Egypt or Mesopotamia, there were no great rivers feeding fertile soil, just mountains, hills, and scrubland with poor, rocky soil. There were few mineral deposits or other natural resources that could be used or traded with other lands. As it happens, there are iron deposits in Greece but its use was not yet known by the Mycenaeans. They thus learned to cultivate olives to make olive oil and grapes to make wine, two products in great demand all over the ancient world that were profitable enough to sustain seagoing trade. It is also likely that the difficult conditions in Greece helped lead the Mycenaeans to be so warlike, as they raided each other and their neighbors in search of greater wealth and opportunity.

The “Mask of Agamemnon,” a Mycenaean funerary mask discovered by a German archaeologist in the late nineteenth century.

The Mycenaeans were a society that glorified noble warfare. As war is depicted in the Iliad, battles consisted of the elite noble warriors of each side squaring off against each other and fighting one-on-one, with the rank-and-file of poorer soldiers providing support but usually not engaging in actual combat. In turn, Mycenaean ruins (and tombs) make it abundantly clear that most Mycenaeans were dirt-poor farmers working with primitive tools, lorded over by bronze-wielding lords who demanded labor and wealth. Foreign trade was in service to providing luxury goods to this elite social class, a class that was never politically united but instead shared a common culture of warrior-kings and their armed retinues. Some beautiful artifacts and amazing myths and poems have survived from this civilization, but it was also one of the most predatory civilizations we know about from ancient history.

The Collapse of the Bronze Age

The Bronze Age at its height witnessed several large empires and peoples in regular contact with one another through both trade and war. The pharaohs of the New Kingdom corresponded with the kings and queens of the Hittite Empire and the rulers of the Kassites and Assyrians; it was normal for rulers to refer to one another as “brother” or “sister.” Each empire warred with its rivals at times, but it also worked with them to protect trade routes. Certain Mesopotamian languages, especially Akkadian, became international languages of diplomacy, allowing travelers and merchants to communicate wherever they went. Even the warlike and relatively unsophisticated Mycenaeans played a role on the periphery of this ongoing network of exchange.

That said, most of the states involved in this network fell into ruin between 1200 – 1100 BCE. The great empires collapsed, a collapse that it took about 100 years to recover from, with new empires arising in the aftermath. There is still no definitive explanation for why this collapse occurred, not least because the states that had been keeping records stopped doing so as their bureaucracies disintegrated. The surviving evidence seems to indicate that some combination of events – some caused by humans and some environmental – probably combined to spell the end to the Bronze Age.

Around 1050 BCE, two of the victims of the collapse, the New Kingdom of Egypt and the Hittite Empire, left clear indications in their records that drought had undermined their grain stores and their social stability. In recent years archaeologists have presented strong scientific evidence that the climate of the entire region became warmer and more arid, supporting the idea of a series of debilitating droughts. Even the greatest of the Bronze Age empires existed in a state of relative precarity, relying on regular harvests in order to not just feed their population, but sustain the governments, armies, and building projects of their states as a whole. Thus, environmental disaster could have played a key role in undermining the political stability of whole regions at the time.

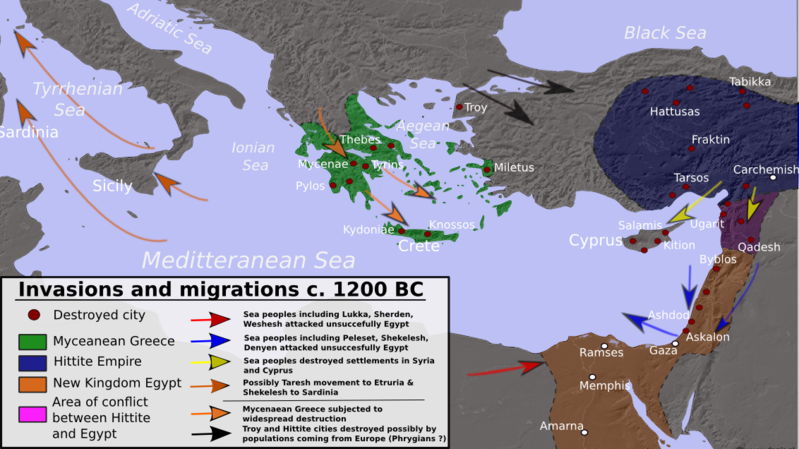

Even earlier, starting in 1207 BCE, there are indications that a series of invasions swept through the entire eastern Mediterranean region. The New Kingdom of Egypt survived the invasion of the “sea people,” some of whom historians are now certain went on to settle in Canaan (they are remembered in the Hebrew Bible as the Philistines against whom the early Hebrews struggled), but the state was badly weakened in the process. In the following decades, other groups that remain impossible to identify precisely appear to have sacked the Mycenaean palace complexes and various cities across the Near East. While Assyria in northern Mesopotamia survived the collapse, it lost its territories in the south to Elan, a warlike kingdom based in present-day southern Iran.

The identity of the foreign invaders is not clear from the scant surviving record. One distinct possibility is that the “bandits” (synonymous in many cases with “barbarians” in ancient accounts) blamed for destabilizing the region might have been a combination of foreign invaders and peasants displaced by drought and social chaos who joined the invasions out of desperation. It is thus easy to imagine a confluence of environmental disaster, foreign invasion, and peasant rebellion ultimately destroying the Bronze Age states. What is clear is that the invasions took place over the course of decades – from roughly 1180 to 1130 BCE – and that they must have played a major role in the collapse of the Bronze Age political and economic system.

While the precise details are impossible to pin down, the above map depicts likely invasion routes during the Bronze Age Collapse. More important than those details is the result: the fall of almost all of the Bronze Age kingdoms and empires.

For roughly 100 years, from 1200 BCE to 1100 BCE, the networks of trade and diplomacy considered above were either disrupted or destroyed completely. Egypt recovered and new dynasties of pharaohs were sometimes able to recapture some of the glory of the past Egyptian kingdoms in their building projects and the power of their armies, but in the long run Egypt proved vulnerable to foreign invasion from that point on. Mycenaean civilization collapsed utterly, leading to a Greek “dark age” that lasted some three centuries. The Hittite Empire never recovered in Anatolia, while in Mesopotamia the most noteworthy survivor of the collapse – the Assyrian state – went on to become the greatest power the region had yet seen.

The Iron Age

The decline of the Bronze Age led to the beginning of the Iron Age. Bronze was dependent on functioning trade networks: tin was only available in large quantities from mines in what is today Afghanistan, so the collapse of long-distance trade made bronze impossible to manufacture. Iron, however, is a useful metal by itself without the need of alloys (although early forms of steel – iron alloyed with carbon, which is readily available everywhere – were around almost from the start of the Iron Age itself). Without copper and tin available, some innovative smiths figured out that it was possible, through a complicated process of forging, to create iron implements that were hard and durable. Iron was available in various places throughout the Middle East and Mediterranean regions, so it did not require long-distance trade as bronze had. The Iron Age thus began around 1100 BCE, right as the Bronze Age ended.

One cautionary note in discussing this shift: iron was very difficult to work with compared to bronze, and its use spread slowly. For example, while iron use became increasingly common starting in about 1100 BCE, the later Egyptian kingdoms did not use large amounts of iron tools until the seventh century BCE, a full five centuries after the Iron Age itself began. Likewise, it took a long time for “weaponized” iron to be available, since making iron weapons and armor that were hard enough to endure battle conditions took a long time. Once trade networks recovered, bronze weapons were still the norm in societies that used iron tools in other ways for many centuries.

Outside of Greece, which suffered its long “dark age” following the collapse of the Bronze Age, a number of prosperous societies and states emerged relatively quickly at the start of the Iron Age. They re-established trade routes and initiated a new phase of Middle Eastern politics that eventually led to the largest empires the world had yet seen.

Iron Age Cultures and States

The region of Canaan, which corresponds with modern Palestine, Israel, and Lebanon, had long been a site of prosperity and innovation. Merchants from Canaan traded throughout the Middle East, its craftsmen were renowned for their work, and it was even a group of Canaanites – the Hyksos – who briefly ruled Egypt during the Second Intermediate Period. Along with their neighbors the Hebrews, the most significant of the ancient Canaanites were the Phoenicians, whose cities (politically independent but united in culture and language) were centered in present-day Lebanon.

The Phoenicians were not a particularly warlike people. Instead, they are remembered for being travelers and merchants, particularly by sea. They traveled farther than any other ancient people; sometime around 600 BCE, according to the Greek historian Herodotus, a Phoenician expedition even sailed around Africa over the course of three years (if that actually happened, it was an achievement that would not be accomplished again for almost 2,000 years). The Phoenicians established colonies all over the shores Mediterranean, where they provided anchors in a new international trade network that eventually replaced the one destroyed with the fall of the Bronze Age. Likewise, Phoenician cities served as the crossroads of trade for goods that originated as far away as England (metals were mined in England and shipped all the way to the Near East via overland routes). The most prominent Phoenician city was Carthage in North Africa, which centuries later would become the great rival of the Roman Republic.

Phoenician trade was not, however, the most important legacy of their society. Instead, of their various accomplishments, none was to have a more lasting influence than that of their writing system. As early as 1300 BCE, building on the work of earlier Canaanites, the Phoenicians developed a syllabic alphabet that formed the basis of Greek and Roman writing much later. A syllabic alphabet has characters that represent sounds, rather than characters that represent things or concepts. These alphabets are much smaller and less complex than symbolic ones. It is possible for a non-specialist to learn to read and write using a syllabic alphabet much more quickly than using a symbolic one (like Egyptian hieroglyphics or Chinese characters). Thus, in societies like that of the Phoenicians, there was no need for a scribal class, since even normal merchants could become literate. Ultimately, the Greeks and then the Romans adopted Phoenician writing, and the alphabets used in most European languages in the present is a direct descendant of the Phoenician one as a result. To this day, the English word “phonetic,” meaning the correspondence of symbols and sounds, is directly related to the word “Phoenician.”

The Phoenician mastery of sailing and the use of the syllabic alphabet were both boons to trade. Another was a practice – the use of currency – originating in the remnants of the Hittite lands. Lydia, a kingdom in western Anatolia, controlled significant sources of gold (giving rise to the Greek legend of King Midas, who turned everything he touched into gold). In roughly 650 BCE, the Lydians came up with the idea of using lumps of gold and silver that had a standard weight. Soon, they formalized the system by stamping marks into the lumps to create the first true (albeit crude) coins, called staters. Currency revolutionized ancient economics, greatly increasing the ability of merchants to travel far afield and buy foreign goods, because they no longer had to travel with huge amounts of goods with them to trade. It also made tax collection more efficient, strengthening ancient kingdoms and empires.

Empires of the Iron Age

While the Phoenicians played a major role in jumpstarting long-distance trade after the collapse of the Bronze Age, they did not create a strong united state. Such a state emerged farther east, however: alone of the major states of the Bronze Age, the Assyrian kingdom in northern Mesopotamia survived. Probably because of their extreme focus on militarism, the Assyrians were able to hold on to their core cities while the states around them collapsed. During the Iron Age, the Assyrians became the most powerful empire the world had ever seen. The Assyrians were the first empire in world history to systematically conquer almost all of their neighbors using a powerful standing army and go on to control the conquered territory for hundreds of years. They represented the pinnacle of military power and bureaucratic organization of all of the civilizations considered thus far. (Note: historians of the ancient world distinguish between the Bronze Age and Iron Age Assyrian kingdoms by referring to the latter as the Neo-Assyrians. The Neo-Assyrians were direct descendants of their Bronze Age predecessors, however, so for the sake of simplicity this chapter will refer to both as the Assyrians.)

The Assyrians were shaped by their environment. Their region in northern Mesopotamia, Ashur, has no natural borders, and thus they needed a strong military to survive; they were constantly forced to fight other civilized peoples from the west and south, and barbarians from the north. The Assyrians held that their patron god, a god of war also called Ashur, demanded the subservience of other peoples and their respective gods. Thus, their conquests were justified by their religious beliefs as well as a straightforward desire for dominance. Eventually, they dispatched annual military expeditions and organized conscription, fielding large standing armies of native Assyrian soldiers who marched out every year to conquer more territory.

The period of political breakdown in Mesopotamia following the collapse of the Bronze Age ended in about 880 BCE when the Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II began a series of wars to conquer Mesopotamia and Canaan. Over the next century, the (Neo-)Assyrians became the mightiest empire yet seen in the Middle East. They combined terror tactics with various technological and organizational innovations. They would deport whole towns or even small cities when they defied the will of the Assyrian kings, resettling conquered peoples as indentured workers far from their homelands. They tortured and mutilated defeated enemies, even skinning them alive, when faced with any threat of resistance or rebellion. The formerly-independent Phoenician city-states within the Assyrian zone of control surrendered, paid tribute, and deferred to Assyrian officials rather than face their wrath in battle.

The Assyrians were the most effective military force of the ancient world up to that point. They outfitted their large armies with well-made iron weapons (they appear to be the first major kingdom to manufacture iron weapons in large numbers). They invented a messenger service to maintain lines of communication and control, with messengers on horseback and waystations to replace tired horses, so that they could communicate across their empire. All of their conquered territories were obliged to provide annual tributes of wealth in precious metals and trade goods which funded the state and the military.

The Assyrians introduced two innovations in military technology and organization that were of critical importance: a permanent cavalry, the first of any state in the world, and a large standing army of trained infantry. It took until the middle of the eighth century BCE for selective breeding of horses to produce real “war horses” large enough to carry a heavily armed and armored man into and through an entire battle. The Assyrians adopted horse archery from the barbarians they fought from the north, which along with swords and short lances wielded from horseback made chariots permanently obsolete. The major focus of Assyrian taxation and bureaucracy was to keep the army funded and trained, which allowed them to completely dominate their neighbors for well over a century.

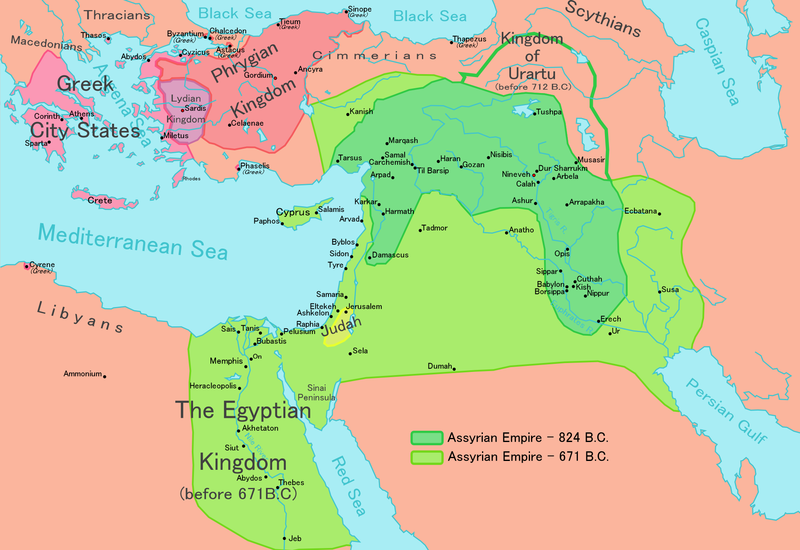

By the time of the reign of Assyrian king Tiglath-Pilezer III (r. 745 – 727 BCE), the Assyrians had pushed their borders to the Mediterranean in the west and to Persia (present-day Iran) in the east. Their conquests culminated in 671 BCE when king Esarhaddon (r. 681 – 668 BCE) invaded Egypt and conquered not only the entire Egyptian kingdom, but northern Nubia as well. This is the first time in history that both of the founding river valleys of ancient civilization, those of the Nile and of Mesopotamia, were under the control of a single political entity.

The expansion of the Assyrian Empire, originating from northern Mesopotamia.

The style of Assyrian rule ensured the hatred of conquered peoples. They demanded constant tribute and taxation and funneled luxury goods back to their main cities. They did not try to set up sustainable economies or assimilate conquered peoples into a shared culture, instead skimming off the top of the entire range of conquered lands. Their style of rule is well known because their kings built huge monuments to themselves in which they boasted about the lands they conquered and the tribute they exacted along the way.

While their subjects experienced Assyrian rule as militarily-enforced tyranny, Assyrian kings were proud of the cultural and intellectual heritage of Mesopotamia and supported learning and scholarship. The one conquered city in their empire that was allowed a significant degree of autonomy was Babylon, out of respect for its role as a center of Mesopotamian culture. Assyrian scribes collected and copied the learning and literature of the entire Middle East. Sometime after 660 BCE, the king Asshurbanipal ordered the collection of all of the texts of all of his kingdom, including the ones from conquered lands, and he went on to create a massive library to house them. Parts of this library survived and provide one of the most important sources of information that scholars have on the beliefs, languages, and literature of the ancient Middle East.

The Assyrians finally fell in 609 BCE, overthrown by a series of rebellions. Their control of Egypt lasted barely two generations, brought to an end when the puppet pharaoh put in place by the Assyrians rebelled and drove them from Egypt. Shortly thereafter, a Babylonian king, Nabopolassar, led a rebellion that finally succeeded in sacking Nineveh, the Assyrian capital. The Babylonians were allied with clans of horse-riding warriors in Persia called the Medes, and between them the Assyrian state was destroyed completely. Nabopolassar went on to found the “Neo-Babylonian” empire, which became the most important power in Mesopotamia for the next few generations.

The Neo-Babylonians adopted some of the terror tactics of the Assyrians; they, too, deported conquered enemies as servants and slaves. Where they differed, however, was in their focus on trade. They built new roads and canals and encouraged long-distance trade throughout their lands. They were often at war with Egypt, which also tried to take advantage of the fall of the Assyrians to seize new land, but even when the two powers were at war Egyptian merchants were still welcome throughout the Neo-Babylonian empire.

A combination of flourishing trade and high taxes led to huge wealth for the king and court, and among other things led to the construction of noteworthy works of monumental architecture to decorate their capital. The Babylonians inherited the scientific traditions of ancient Mesopotamia, becoming the greatest astronomers and mathematicians yet seen, able to predict eclipses and keep highly detailed calendars. They also created the zodiac used up to the present in astrology, reflecting the age-old practice of both science and “magic” that were united in the minds of Mesopotamians. In the end, however, they were the last of the great ancient Mesopotamian empires that existed independently. Less than 100 years after their successful rebellion against the Assyrians, they were conquered by what became the greatest empire in the ancient world to date: the Persians, described in a following chapter.