Chapter 9: Fascism

Disappointment

In many ways, World War I was what truly ended the nineteenth century. It undermined the faith in progress that had grown, despite all of its setbacks, throughout the nineteenth century among many, perhaps most, Europeans. The major political movements of the nineteenth century seemed to have succeeded: everywhere in Europe nations replaced empires (nationalism). Europe controlled more of the world in 1920 than it ever had or ever would again (imperialism). In the aftermath of the war, almost every government in Europe, even Germany, was a republican democracy based on the rule of law (liberalism). Even socialists had cause to celebrate: there was a nominally Marxist state in Russia and socialist parties were powerful and militant all across Europe. The old order of monarchs and nobles was rendered all but obsolete, with noble titles holding on as nothing more than archaic holdovers from the past in nearly every country. In addition, of course, technology continued to advance apace.

Despite the success of all of those movements, however, with all of the hopes and aspirations of their supporters over the last century, Europe had degenerated into a horrendous and costly war. The war had not purified and invigorated the great powers; they were all left reeling, weakened, and at a loss for how to prevent a future war. Science had advanced, but its most noteworthy accomplishment was the production of more effective weapons. The global empires remained, but the seeds of their dissolution were already present.

The results were bitterness and reprisals. The Treaty of Versailles that ended the war imposed harsh penalties on Germany, returning Alsace and Lorraine to France and imposing a massive indemnity on the defeated country. The Treaty also required Germany to accept the “war guilt clause,” in which it assumed full responsibility for the war having started in the first place. Simultaneously, the Austrian Empire collapsed, with Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and the new Balkan nation of Yugoslavia all becoming independent countries and Austria a short-lived republic. Almost no one would have believed that another “Great War” would occur in twenty years.

In other words, World War I did not resolve any of the problems or international tensions that had started it. Instead, it made them worse because it proved how powerful and devastating modern weapons were, and it also demonstrated that no single power was likely to be able to assert its dominance. France and Britain went out of their way in blaming Germany for the conflict, while in Germany itself, those on the right believed in the conspiracy theory in which communists and Jews had conspired to sabotage the German war effort – this was later called the “Stab in the Back” myth. Thus, many Germans felt they had been wronged twice: they had not “really” lost the war, yet they were forced to pay outrageous indemnities to the “victors.”

It was in this context of anger and disappointment that fascism and its racially-obsessed offshoot Nazism arose. World War I provided the trauma, the bloodshed, and the skepticism toward liberalism and socialism that underwrote the rise of fascism. Fascism was a modern conservatism, a conservatism that clung to its mania for order and hierarchy, but which did not seek a return to the days of feudalism and monarchy. It was a populist movement, a movement of the people by the people, but instead of petty democratic bickering, it glorified the (imagined) nation, a nation united by a movement and an ethos.

Fascism

Fascism centered on the glorification of the state, the rejection of liberal individualism, and an incredible emphasis on hierarchy and authority. Fascist movements sprung up right as the war ended. The term fascism was invented by the Italian Fascist Party itself, based on the term fascii: a bundle of sticks with an axe embedded in the middle. Symbolically, the sticks are weak individually but strong as a group, and the axe represented the power over life and death. In ancient Rome, the bodyguards of the Roman consuls carried fascii as a badge of authority over war, peace, law, and death, and that symbolism appealed to the Italian Fascists.

By the early 1920s, there were fascist movements in many European countries, all of them agitating for some kind of right-wing revolution against democracy and socialism. One place of particular note in the early history of fascism was France. There, a right-wing monarchist group called Actione Française had existed since the Dreyfus Affair, but it transformed itself into a French fascist group despite still clinging to monarchist and traditional Catholic ideologies. When Germany defeated France in World War II, the Nazis found a large contingent of right-wing Frenchmen who were all too happy to create a home-grown French fascist state (a fact that many in France tried their best to forget after the war). Likewise, when the Nazis seized power in various places in Eastern Europe, they often found it expedient to simply work with or appoint the already-existing local fascist groups to power.

Fascism was a twentieth-century phenomenon, but its ideological roots were firmly planted in the nineteenth century. Mostly obviously, fascism was an extreme form of nationalism. The nation was not just the home of a “people” in fascism, it was everything. The nation became a mythic entity that had existed since the ancient past, and fascists claimed that the cultural traits and patterns of the nation defined who a person was and how they regarded the world.

The confusing jumble of what defined a nation in the first place often took on explicitly racial, and racist, terms among fascist groups. Now, Germans were not just people who spoke German in Central Europe; they were the German (or “Aryan,” the term itself nothing more than a pseudo-scholarly jumble of linguistic history and racist nonsense) “race.” French fascists talked about the bloodlines of the ancient Gauls that supposedly survived despite the “pollution” of the Roman invasions in the ancient past. Likewise, Mussolini and the Italian Fascists claimed that “the Italians” were the direct descendants of the most glorious tradition of the ancient Roman Empire and were destined to create a new, even greater empire. The pseudo-sciences of race had arisen in the late nineteenth century as perverse offshoots of genuine advances in biology and the natural sciences. Fascism was, among other things, a cultural movement that found in “scientific” racism a profoundly compatible doctrine: the “scientific” proof in the rightness of the racial nation’s rise to power.

At first sight, one surprising aspect of fascism was that many fascists were former communists – Benito Mussolini, the leader of the Italian Fascist Party, had been a prominent member of the Italian Communist Party before World War I. What fascism and communism had in common was a rejection of bourgeois parliamentary democracy. They both sought transcendent political and social orders that went beyond “mere” parliamentary compromise. The major difference between them was that fascists discovered in World War I that most people were not willing to die for their social class, but they were willing to die for their nation. Fascism was, in part, a kind of collective movement that substituted nationalism for the class war. All classes would be united in the nation, fascists believed, for the greater glory of the race and movement.

Italian Fascism

As noted above, the very term “fascist” is a product of the first fascist group to seize control of a powerful country: the Italian Fascist Party. Italian Fascism was an invention of Italian army veterans. Most important among them was Benito Mussolini, a combat veteran who had welcomed the war as a cleansing, invigorating opportunity for Italy to grow into a more powerful nation. He was deeply disappointed by its lackluster aftermath. Italy, having joined with England and France against Germany and Austria in hopes of seizing territory from the Austrians, was given very little land after the war. Thus, to Mussolini and many other Italians, the war had been especially pointless.

The Fascists, who started out with a mere 100 members in the northern Italian city of Milan, grew rapidly because of the incredible social turmoil in Italy in 1919 and 1920. Italy had a powerful communist movement, one that was inspired by and linked to the Soviet Union’s recent birth and the success of the communist revolution in Russia. After the war, a huge strike wave struck Italy and many poor Italians in the countryside seized land from the semi-feudal landlords who still dominated rural society. There was genuine concern among traditional conservatives, the Church, business leaders, and the middle classes that Italy would undergo a communist revolution just as had occurred in Russia – at the time Russia was still in the midst of its civil war between the “Red” Bolsheviks and the anti-communist coalition known as the Whites. By 1920 the Reds were clearly winning.

The Fascists organized themselves into paramilitary units of thugs known as the Blackshirts (for their party-issued uniforms) and engaged in open street fighting against communists, breaking up strikes, attacking communist leaders, destroying communist newspaper offices, and intimidating voters from communist-leaning neighborhoods and communities. They were often tacitly aided by the police, who rounded up communists but ignored Fascist lawbreaking as long as it was directed against the communists. Likewise, business leaders started funding the Fascists as a kind of guarantee against further gains by communists. Fascist politicians ran for office in the Italian parliament while their gangs of thugs terrorized the opposition.

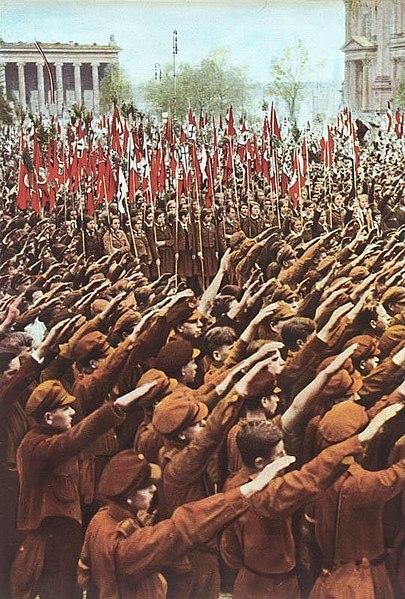

In 1922, the weak-willed King of Italy, Vittorio Emanuele III, appointed Mussolini Prime Minister, seeing in Mussolini a bulwark against the threat of communism (and caving in to the growing strength of the Fascist Party). Fascists from all over Italy converged in a famous “March on Rome,” a highly staged piece of political theater meant to demonstrate Fascist unity and strength. Mussolini then set out to destroy Italian democracy from within. From 1922 to 1926 Mussolini and the Fascists manipulated the Italian parliament, intimidated political opponents or actually had them murdered, and succeeded finally in eliminating party politics and a free press. The Fascist party became the only legal party in Italy and the police apparatus expanded dramatically. Mussolini’s official title was

Il Duce: “The Leader,” and his authority over every political decision was absolute. The Fascist motto was “believe, obey, fight,” a distant parody of the French liberal motto (from the French Revolution) “liberty, equality, fraternity.”

Mussolini immediately understood the importance of appearances. The 1920s was the early age of mass media, especially radio, and an intrinsic part of fascism was public spectacle. Mussolini staged enormous public exhibitions and rallies and he carefully controlled how he was portrayed in the media – the press was forbidden to mention his age or his birthday, to give the illusion that he never aged. He was always on the move, usually in a race car, and usually accompanied by models, actresses, and socialites years his junior. He spoke about his own “animal magnetism” and often walked around without a shirt on as a kind of (would be) herculean archetype.

Officially, Italian Fascism promised to end the class conflict that lay at the heart of socialist ideology by favoring what it called “corporatism” over mere capitalism. Corporatism was supposed to be a unified decision-making system in which workers and business owners would serve on joint committees to control work. In fact, the owners derived all of the benefits; trade unions were banned and the plight of workers degenerated without representation.

What Italian Fascism did do for the Italian people was essentially ideological and, in a sense, emotional: it directed youth movements and recreational clubs and sought the involvement of all Italians. It glorified the idea of the Italian people and in turn many actual Italians did come to feel great national pride, even if they were working in difficult conditions in a stagnant economy. In turn, Fascist propaganda tried to inculcate Italian pride and Fascist identity among Italian citizens, while Fascist-led police forces targeted would-be dissidents, sentencing thousands to prison terms or internal exile in closed prison villages (not unlike some of the Russian gulags that would exemplify a different but related totalitarian system to the east).

While Mussolini was often praised in the foreign press, including in American newspapers and magazines, for accomplishments like making (a few) Italian trains run on time, in the long term the Fascist government proved to be inefficient and often outright ineffectual. Mussolini himself, convinced of his own genius, made arbitrary and often foolish decisions, especially when it came to building up and training the Italian military. The circle of Fascist leaders around him were largely corrupt sycophants who lied to Mussolini about Italy’s strength and prosperity to keep him happy. When World War II began in 1939, the Italian forces were revealed to be poorly trained, equipped, and led.

The Weimar Republic

One place in Europe during the interwar period stands out as a microcosm of the political and cultural struggles occurring elsewhere: Weimar Germany. Named after the resort town in which its constitution was written in early 1919, the Weimar Republic represented a triumphant culmination of liberalism. Its constitution guaranteed universal suffrage for men and women, fundamental human rights, and the complete rejection of the remnants of monarchism. Unfortunately, the government of the new republic was deeply unpopular among many groups, including right-wing army veterans like a young Adolf Hitler.

One great lie that poisoned the political climate of the Weimar Republic was, as mentioned above, the “stab-in-the-back” myth. Toward the end of World War I, Germany was losing. Its own General Staff informed the Kaiser of this fact; with American troops and munitions flooding in, it was simply a matter of time before the Allies were able to march in force on Germany. As defeat loomed, however, the military leaders Hindenburg and Ludendorff, along with the Kaiser himself, concocted the idea that Germany could have kept fighting, and won, but instead public commitment to the war wavered because of agitators on the home front and saboteurs who crippled military supply lines. Usually, according to the conspiracy theory, those responsible were some combination of Jews and communists (and, of course, Jewish communists). This was an outright lie, but it was a convenient lie that the political right in Germany could cling to, blaming “Jewish saboteurs” and “Bolshevik agents” for Germany’s loss.

The Versailles Treaty had also required Germany to disarm – the German army went from millions of men to a mere 100,000 soldiers. It was forbidden from building heavy military equipment or having a fleet of more than a handful of warships. Given the social prestige and power associated with the German military before the war, this was an enormous blow to German pride. While the nations of Europe pledged to pursue peaceful resolutions to their problems in the future, many Germans were still left with a sense of vulnerability, particularly as the Bolsheviks cemented their control by the end of the 1920s in Russia.

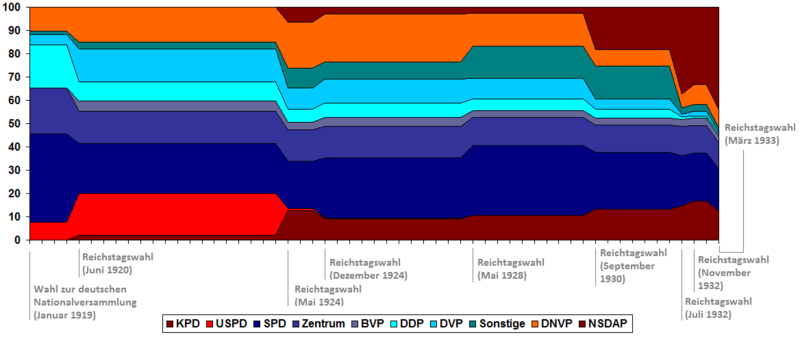

Neither did the Weimar government itself inspire much confidence. Its parliament, the Reichstag, was trapped in an almost perpetual state of political deadlock. Its constitution stipulated that voting was proportional, with the popular vote translated into a corresponding number of seats for the various political parties. Unfortunately, given the vast range of political allegiances present in German society, there were fully thirty-two different parties, representing not just elements of the left – right political spectrum, but regional and religious identities as well. The most powerful parties were those of the far left, the communists, and the far right, initially monarchists and conservative Catholics, with the Nazis rising to prominence at the end of the 1920s. Thus, it was nearly impossible for the Reichstag to govern, with the various parties undermining one another’s goals and coalition governments crumbling as swiftly as they formed.

Simultaneously, the Weimar Republic faced ongoing economic issues, which fed into the resentment of most Germans toward the terms of the Versailles Treaty and its reparation payments (set to 132 billion gold marks annually, although that amount was renegotiated and lowered over the course of the decade). The actual economic impact of those payments is still debated by historians; what is not debated is that Germans regarded them as utterly unjust, since they felt that all of the countries of Europe were responsible for World War I, not just Germany. Especially in moments of economic crisis, many otherwise “ordinary” Germans looked to political extremists for possible solutions; to cite the most important example, the electoral fortunes of the Nazi party rose and fell in an inverse relationship to the health of the German economy.

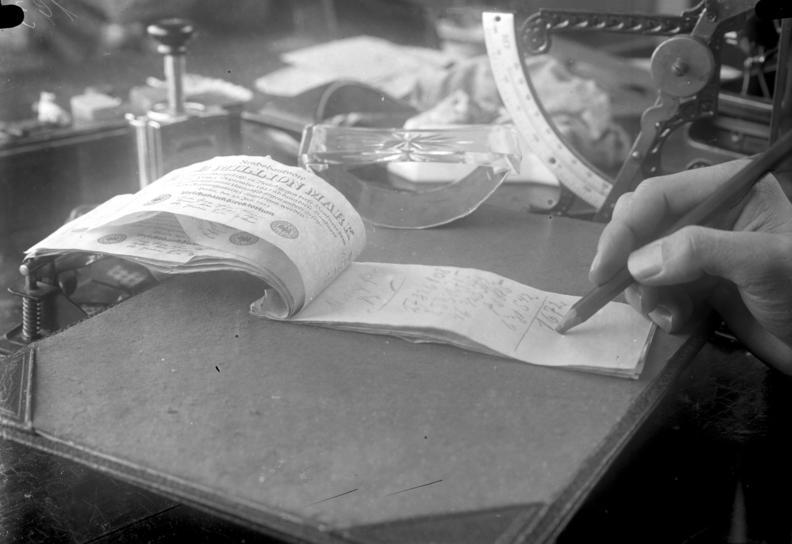

The economy of Germany underwent a severe crisis less than five years after the end of the war. In 1923, unable to make its payments, the Weimar government requested new negotiations. The French responded by seizing the mineral-rich Ruhr Valley. In order to pay striking workers, the government simply printed more money, thereby undermining its value. This, in turn, led to hyperinflation: the German Mark simply collapsed as a currency, with one American dollar being worth nearly 10,000,000,000 marks by the end of the year. Workers were paid in wheelbarrows full of cash at the start of their lunch break so they had time to buy a few groceries before inflation forced shopkeepers to raise prices by the afternoon.

In the course of a year, Germans who had spent their lives carefully building up savings saw those savings rendered worthless. This inspired anger and resentment among common people who might otherwise not be attracted to extremist solutions. The situation stabilized in 1924 after emergency negotiations overseen by American banks resulted in a new stabilized currency, but for many people in Germany their experience of democracy thus far had been disastrous. It was in this context of economic instability and political dysfunction that an extreme right-wing fringe group from the southern German state of Bavaria, the National Socialist German Workers Party, began to attract attention.

The Nazis

Any discussion of the Nazis must start with Adolf Hitler. It is impossible to overstate Hitler’s importance to Nazism: his own private obsessions became state policy and were used as the justification for war and genocide. His unquestionable powers of public speaking and political maneuvering transformed the Nazis from a small fringe group to a major political party, and while he was largely ineffective as a practical decision-maker, he remained central to the image of strength, vitality, and power that the Nazis associated with their state. Hitler was also one of the three “greatest” murderers of the twentieth century, along with Josef Stalin of the Soviet Union and Mao Tse-Tung of China. His obsession with a racialized, murderous vision of German power translated directly into both the Holocaust of the European Jews and World War II itself.

Nothing about Hitler’s biography would seem to suggest his rise to power, however. Hitler was born in Austria in 1889, a citizen of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. He dreamed of being an artist as a young man, but was rejected by the Academy of Fine Arts in the Austrian capital of Vienna – many of his works survive, depicting boring, uninspired, and moderately well-executed Austrian landscapes. Listless and lazy, but convinced from adolescence of his own greatness, Hitler invented the idea that the rejection was due not to his own lack of talent, but because of a shadowy conspiracy that sought to undermine his rise to prominence.

For several years before the outbreak of World War I, Hitler lived in Vienna in flophouses, cheap hotels for homeless men, and there he discovered right-wing politics and cultivated a growing hatred for Austria’s ethnic and linguistic diversity. Hitler spent his days drifting around Vienna, absorbing the rampant anti-Semitism of Austrian society and developing his own theories about Jews and other “foreign” influences. Likewise, he read popular works of racist pseudo-scholarship that glorified a fabricated version of German history. It was in Vienna that he discovered his own talent for public speaking, as well. The first groups he held enraptured by his improvised speeches about German greatness and the Jewish (and Slavic) peril were his fellow flophouse residents.

Hitler regarded the fact that Germany and Austria were separate countries as a terrible historical error. He hated the weak Austrian government and fled to Germany rather than serve his required military service in Austria. Much to his delight, World War I broke out when he was already in Germany; he enthusiastically volunteered for the German army and served at the western front, surviving both a poison gas attack and shrapnel from an exploding shell. Unlike most veterans of the war, Hitler experienced combat and service in the trenches as exhilarating and fulfilling, and he was completely without compassion – he would later shock his own generals during World War II by his callousness in spending German lives to achieve symbolic military objectives.

After the war, he was sent by the army to the southern German city of Munich, which was full of angry, disenchanted army veterans like himself. His assignment was to investigate a small right-wing group, the German Workers Party. His “investigation” immediately transformed into enthusiasm, finding like-minded conservatives who loathed the Weimar Republic and blamed socialism and something they called “international Jewry” for the defeat of Germany in the war. He swiftly rose in the ranks of the Nazis, becoming the Führer (“Leader”) of the party in 1921 thanks to his outstanding command of oratory and his ability to browbeat would-be political opponents – he unceremoniously ejected the party’s founder in the process. Under Hitler’s leadership, the party was renamed the National Socialist German Workers Party (“Nazi” is derived from the German word for “national”), and it adopted the swastika, long a favorite of racist pseudo-historians looking for the ancient roots of the fabricated “Aryan” race, as its symbol.

What made Nazi ideology distinct from that of their Italian Fascist counterparts was its emphasis on biology. The Nazis believed that races were biological entities, that there was something inherent in the blood of each “race” that had a direct impact on its ability to create or destroy something as vague as “true culture.” According to Nazi ideology, only the so-called Aryan race, Germans especially but also including related white northern Europeans like the Danes, the Norwegians, and the English, had ever created culture or been responsible for scientific progress. Other races, including some non-European groups like the Persians and the Japanese, were considered “culture-preserving” races who could at least enjoy the benefits of true civilization. At the bottom end of this invented hierarchy were “culture-destroying” races, most importantly Jews but also including Slavs, like Russians and Poles. In the great scheme for the Nazi new world order, Jews would be somehow pushed aside entirely and the Slavs would be enslaved as manual labor for “Aryans.”

Hitler himself invented this crude scheme of racial potential, codifying it in his autobiography Mein Kampf (see below). He was obsessed with the idea that the German race teetered on the brink of extinction, tricked into accepting un-German concepts like democracy or communism and foolishly interbreeding with lesser races. Behind all of this was, according to him, the Jews. Hitler claimed that the Jews were responsible for every disaster in German history; the loss of World War I was just the latest in a long string of catastrophes for which the Jews were responsible. The Jews had invented communism, capitalism, pacifism, liberalism, democracy…anything and everything that supposedly weakened Germany from Hitler’s perspective.

In 1921, under Hitler’s leadership, the Nazis organized a paramilitary wing called the Stormtroopers (SA in their German acronym). In 1923, inspired by the Italian Fascists’ success in seizing power in Italy, Hitler led his fellow Nazis in an attempt to seize the regional government of the German region of Bavaria, of which Munich is the capital. This would-be revolution is remembered as the “Beer-Hall Putsch.” It failed, but Hitler used his ensuing trial as a national stage, as the proceedings were widely reported on by the German press. The court officials, who sympathized with his politics, gave him and his followers ludicrously short sentences in minimum security prisons, a sentence Hitler spent dictating his autobiography, Mein Kampf (“My Struggle”), to the Nazi party’s secretary, Rudolf Hess.

When he was released in nine months (including time served and recognition of his good behavior), Hitler was a minor national celebrity on the right. The Nazis were still a fringe group, but they were now a fringe group that people had heard of. Nazi Stormtroopers harassed leftist groups and engaged in brawls with communist militants. The party created youth organizations, workers’ and farmers’ wings, and women’s groups. They held rallies constantly, creating early versions of “interest groups” to gauge the issues that attracted the largest popular audience. Even so, they did not have mass support in the 1920s – they only won 2.6% of the national vote in 1928.

The Great Depression, however, threw the Weimar government and German society into such turmoil that extremists like the Nazis suddenly gained considerable mass appeal. Promising the complete repudiation of the Versailles Treaty, the build-up of the German military, an end to economic problems, and a restoration of German pride and power, the Nazis steadily grew in popularity: an electoral breakthrough in 1930 saw them win 18% of the seats in the Reichstag. In 1932 they won 37% of the national vote, the most they ever won in a free, legal election.

That being noted, the Nazis never came close to winning an actual majority in the Reichstag. They were essentially a strong, combative far-right minority party. Thanks to the advent of the Depression, more “ordinary Germans” than before were attracted to their message, but that message did not seem at the time to be greatly different than the messages of other right-wing parties. That said, the Nazis were masters of fine-tuning their messages for the electorate; most of their propaganda had to do with German pride, unity, and the need for social and economic order and prosperity, not the hatred of Jews or the need to launch attacks on other European nations. They offered themselves as a solution to the inefficiency of the Weimar Republic, not as a potential bloodbath.

In fact, 1932 represented both the high point and what could have been the beginning of the decline of the Nazis as a party. The presidential election that year saw Hitler lose to Hindenburg, who had served as president since 1925, despite his own contempt for democracy. The Nazis lost millions of votes in the subsequent Reichstag election, and Hitler even briefly considered suicide. Unfortunately, in January of 1933, Hindenburg was convinced by members of his cabinet led by a conservative Catholic politician, Franz von Papen, to use Hitler and the Nazis as tools to help dismantle the Weimar state and replace it with a more authoritarian political order. Thus, Hindenburg appointed Hitler chancellor, the second-most powerful political position in the state.

Hitler seized the opportunity to launch a full-scale takeover of the German government. The Reichstag building was set on fire by an unknown arsonist in February, and Hitler blamed the communists, pushing through an emergency measure (the “Reichstag Fire Decree”) that suspended civil rights. That allowed the state to destroy the German Communist Party, imprisoning 20,000 of its members in newly-built concentration camps. Through voter fraud and massive intimidation by the Nazi Stormtroopers, new elections saw the Nazis win 49% in the next election. Soon, with the aid of other conservative parties, the Nazis pushed through the Enabling Act, which empowered Hitler and the presidential cabinet to pass laws by decree. In July, the Nazis outlawed all parties except themselves. By the summer of 1933, the Nazis controlled the state itself, with Hindenburg (impressed by Hitler’s decisiveness) willingly signing off on their measures.

The Nazi government that followed was a mess of overlapping bureaucracies with no clear areas of control, just influence. The Weimar constitution was never officially repudiated, but the letter of laws became far less important than their interpretation according to the “spirit” of Nazism. In lieu of a rational political order, there was a kind of governing principle that one Nazi party member described as “working towards the Führer”: trying to determine the “spirit” of Nazism and abiding by it rather than following specific rules or laws. The only unshakable core principle was the personal supremacy of the Führer, who was supposed to embody Nazism itself.

Nazism was not just a governing philosophy, however. Hitler was obsessed with winning over “ordinary Germans” to the party’s outlook, and to that end the state both bombarded the population with propaganda and sought to alleviate the dismal economic situation of the early 1930s. The Nazi state poured money into a debt-based recovery from the Depression (the economics of the recovery were totally unsustainable, but the Nazi leadership gambled that war would come before the inevitable economic collapse). Employment recovered somewhat as the state funded huge public works and, after he publicly broke with the terms of the Versailles Treaty in 1935, rearmament. Even though there were still food and consumable shortages, many Germans felt that things were better than they had been. The Nazis refused to continue war reparations and soon the rapidly-rebuilding military was staging enormous public rallies.

Ultimately, the Nazi party controlled Germany from 1933 until Germany surrendered to the Allies in World War II in 1945 – that period is remembered as that of the Third Reich, the Nazis’ own term for what Hitler promised would be a “1,000 years” of German dominance. During that time, the Nazis sponsored a full-scale attempt to recreate German culture and society to correspond with their vision of a racialized, warlike, and “purified” German nation. They claimed to have launched a “national revolution” in the name of unifying all Germans in one Volksgemeinschaft: people’s community.

The Nazis targeted almost every conceivable social group with a specific propaganda campaign and encouraged (or required) German citizens to join a specific Nazi league: workers were encouraged to work hard for the good of the state, women were encouraged to produce as many healthy children as possible (and to stay out of the workplace), boys were enrolled in a paramilitary scouting organization, the Hitler Youth, and girls in the League of German Girls, trained as future mothers and domestics. All vocations and genders were united in the glorification of the military and, of course, of the Führer himself (“Heil Hitler” was the official greeting used by millions of German citizens, whether or not they ever joined the Nazi party itself). The purpose of the campaigns was to win the loyalty of the population to the regime and to Hitler personally, and nearly the entire population at least paid lip service to the new norms.

The dark side of both the propaganda and the legal framework of the Third Reich was the suspension of civil rights and the concomitant campaigns against the so-called “enemies” of the German people. The Nazis vilified Jews, as well as other groups like people with disabilities and the Romani (better known as “Gypsies,” although the term itself is something of an ethnic slur). Starting in 1933, the state began a campaign of involuntary sterilizations of disabled and mixed-race peoples. Jewish businesses were targeted for vandalism and Jewish people were attacked. In 1935 the Nazis passed the so-called “Nuremberg Laws” which outlawed Jews from working in various professions, stripped Jews of citizenship, and made sex between Jews and non-Jews a serious crime.

Even as Germans were encouraged to identify with the Nazi state, and joining the Nazi Party itself soon became an excellent way to advance one’s career, the Nazis also held out the threat of imprisonment or death for those who dared defy them. The first concentration camp was opened within weeks of Hitler’s appointment of chancellor in 1933, and a vast web of police forces soon monitored the German population. The most important organization in Nazi Germany was the SS (Schutzstaffel, meaning “protection squadron”), an enormous force of dedicated Nazis with almost unlimited police powers. The SS had the right to hold anyone indefinitely, without trial, in “protective custody” in a concentration camp, and the Nazi secret police, the Gestapo, were merely one part of the SS. This combination of incentives (e.g. propaganda, programs, incentives) and threats (e.g. the SS, concentration camps) helps explain why there was no significant resistance to the Nazi regime from within Germany.

The Spanish Civil War

The first real war launched by fascist forces was not in Italy or Germany, however, but in Spain. The greatest of the European powers in the sixteenth century, Spain had long since sunk into obscurity, commercial weakness, and backwardness. Its society in 1920 was very much like it had been a century earlier: most of the country was populated by poor rural farmers and laborers, and an alliance of the army, Catholic church, and old noble families still controlled the government in Madrid. The king, Alfonso XIII, still held real power, despite his own personal ineptitude. In many ways, Spain was the last place in Europe that clung to the old order of the nineteenth century.

Socialists and liberals were increasingly militant by the early 1920s, and Catalan and Basque nationalists likewise agitated for independence from Spain. From 1923 to 1930, a general named Primo de Rivera acted as a virtual dictator (with the support of the king) trying to drag Spain into the twentieth century by building dams, roads, and sewers. He weakened what representation there was in the state by making government ministers independent of the parliament (the Cortes) and he even managed to lose support in the army by interfering in the promotion of officers.

In 1931, the king abdicated after an anti-monarchist majority took the Cortes. The result was a republic, whose parliament was dominated by liberals and moderate socialists. The parliament pushed through laws that formally separated church and state (for the first time in Spanish history) and redistributed land to the poor, seized from the enormous estates of the richest nobles. Peasants in the countryside went further, attacking churches, convents, and the estates of the nobility. Meanwhile, Spanish communists sought a Russian-style communist revolution and, even further to the left, a substantial anarchist coalition aimed at the complete abolition of government. Thus, the left-center coalition was increasingly beleaguered, as the far left gravitated away and the nobility and clergy joined with the army in an anti-parliamentarian right. Two years of anarchy resulted, from 1933 – 1935.

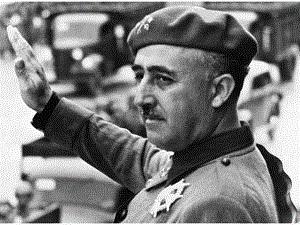

In 1935, as the forces of the right rallied around a general named Francisco Franco, the socialists, liberals, anarchists, and communists formed a Popular Front to fight it. More chaos ensued, with Franco’s forces growing in power and the Popular Front suffering from infighting (i.e. the anarchists, communists, liberals, and nationalist minorities did not work well together). Franco’s traditional conservative forces joined with Spanish fascists, the Falange, soon openly supported by Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. In 1936, Franco’s forces seized several key regions in Spain.

The war began in earnest in that year. It was hugely bloody; probably about 600,000 people died, of which 200,000 were “loyalists” (the blanket term for the pro-republican, or at least anti-monarchical, forces) summarily executed after being captured by the “nationalists” under Franco. Meanwhile, the loyalists carried out atrocities of their own, targeting especially members of the church. One of the iconic moments in the war was the arrival of over 20,000 foreign volunteers on the side of the loyalists, including the Abraham Lincoln Brigade from the United States. Both the American writer Ernest Hemingway and the English writer George Orwell fought in defense of the republic.

While, officially, there was an international non-interventionist agreement among the governments of Europe and the US with regards to Spain, Germany and Italy blatantly violated it and provided both troops and equipment to the nationalist forces. The most effective support provided by Italy or Germany came from the German air force, the

Luftwaffe, which used Spain as a training ground with real targets. The loyalists had no means to fight against planes, so they suffered consistent defeats and setbacks from German bombing raids. Overall, the Spanish Civil War allowed Italy and Germany to “try out” their new armies before committing to a larger war in Europe (Italy, however, did launch a brutal invasion of Ethiopia in 1934 as well).

The nationalists triumphed in early 1939, having cut off the pockets of loyalists off from one another. They were recognized as the legitimate government of Spain internationally, and despite their promises to the contrary, they immediately began carrying out reprisals against the now-defeated loyalists. Franco adopted the title of Caudillo, or leader, in the same manner as Mussolini and Hitler. Where Spain differed from the other fascist powers was that Franco was well aware of its relative weakness and deliberately avoided an expansionist foreign policy; Hitler once spent a fruitless day trying to convince him to join the war once World War II was underway.

Franco’s regime, which united the old nobles, the army, and the Catholic church, controlled the country until Franco’s death in 1975. Just as Spain was one of the last countries still tied to the old political order of kings and nobles after World War I, it was among the last fascistic countries long after Hitler’s Germany and Mussolini’s Italy had fallen.

Image Citations (Wikimedia Commons):

March on Rome – Public Domain

Weimar Electoral Results – Pass3456

Hyperinflation– Creative Commons License

Hitler in WWI – Creative Commons License

Beer Hall Putsch – Creative Commons License

Hitler Youth and League of German Girls – Creative Commons License

Franco– Creative Commons License