The English Civil War and the Glorious Revolution

England was perhaps the most outstanding example of a state in which the absolutist form of monarchy resolutely failed during the seventeenth century, and yet the state itself emerged all the stronger. Ironically, the two most powerful states in Europe during the following century were absolutist France and its political opposite, the first major constitutional monarchy in Europe: the United Kingdom of Great Britain.

Some of the characteristics that historians often associate with modernity are representative governments, capitalist economies, and (relative, in the case of early-modern states) religious toleration. All of those things first converged in England at the end of the seventeenth and start of the eighteenth centuries. Likewise, England would eventually evolve from an important but secondary state in terms of its power and influence to the most powerful nation in the world in the nineteenth century. For those reasons it is worthwhile to devote considerable attention to the case of English politics during that period.

The irony of the fact that England was the first state to move toward “modern” patterns and political dominance is that, at the start of the seventeenth century, England was a relative backwater. Its population was only a quarter of that of France and its monarchy was comparatively weak; precisely as France was reorganizing along absolutist lines, England’s monarchy was beset by powerful landowners with traditional privileges they were totally unwilling to relinquish. The English monarchy ran a kingdom with various ethnicities and divided religious loyalties, many of whom were hostile to the monarchy itself. It was an unlikely candidate for what would one day be the most powerful “Great Power” in Europe.

The English King Henry VIII had broken the official English church – renamed the Church of England – away from the Roman Catholic Church in the 1530s. In the process, he had seized an enormous amount of wealth from English Catholic institutions, mostly monasteries, and used it to fund his own military buildup. Subsequently, his daughter Elizabeth I was able to build up an effective navy (based at least initially on converted merchant vessels) that fought off the Spanish Armada in 1588. While Elizabeth’s long reign (r. 1558 – 1603) coincided with a golden age of English culture, most notably with the works of Shakespeare, the money plundered from Catholic coffers had run out by the end of it.

Despite Elizabeth’s relative toleration of religious difference, Great Britain remained profoundly divided. The Church of England was the nominal church of the entire realm, and only Anglicans could hold public office as judges or members of the British parliament, a law-making body dominated by the gentry class of landowners. In turn, the church was itself divided between an “high church” faction that was in favor of all of the trappings of Catholic ritual versus a “Puritan” faction that wanted an austere, moralistic approach to Christianity more similar to Calvinism than to Catholicism. The Puritans were, in fact, Calvinist in their beliefs (concerning the Elect, predestination, and so on), but were still considered to be full members of the church. Meanwhile, Scotland was largely Presbyterian (Scottish Calvinist), and Ireland – which had been colonized by the English starting in the sixteenth century – was overwhelmingly Catholic. Within English society there were numerous Catholics as well, most of whom remained fairly clandestine in their worship out of fear of persecution.

Thus, the monarchy presided over a divided society. It was also relatively poor, with the English crown overseeing a small bureaucracy and no official standing army. The only way to raise revenue from the rest of the country was to raise royal taxes, which were resisted by the very proud and defensive gentry class (the landowners) as well as the titled nobility. The traditional right of parliament was to approve or reject taxes, but an open question as of the early seventeenth century was whether it had the right to set laws as well. The bottom line is that English kings or queens could not force lawmakers to grant them taxes without having to beg, plead, cajole, and bargain. In turn, the stability of government depended on cooperation between the Crown and the House of Commons, the larger of the two legal bodies in the parliament, which was populated by members of the gentry.

The Stuarts and the English Civil War

While her reign was plagued by these issues, Elizabeth I was a savvy monarch who was very skilled at reconciling opposing factions and winning over members of parliament to her perspective. She also benefited from what was left of the money her father had looted from the English monasteries. This delicate balance started to fall apart with Elizabeth’s death in 1603. She died without an heir (she had never married, rightly recognizing that marriage would undermine her own authority), so her successor was from the Scottish royal house of the Stuarts, fellow royals related to the Tudors. The new king was James I (r. 1603 – 1625), the first of the new royal line to rule England. James was already the king of Scotland when he inherited the English crown, so England and Scotland were politically united and the kingdom of “Great Britain” was born (it was later ratified as a permanent legal reality in 1707 with the “Act of Union” passed by parliament).

James, inspired by developments on the continent, tried to insist on the “royal prerogative,” the right of the king to rule through force of will. He set himself up as an absolute monarch and behaved with noticeable contempt towards members of parliament. Still, England was at peace and James avoided making demands that sparked serious resistance. While members of parliament grumbled about his heavy-handed manner of rule, there were no signs of actual rebellion.

His son, Charles I (r. 1625 – 1649), was a much greater threat from the perspective of parliament. He strongly supported the “high church” faction of the Anglican church just as Puritanism among the common people was growing, and he began to openly encroach on parliamentary authority. While styling himself after Louis XIII of France (to whom he was related), he came to be feared and hated by many of his own people. Charles imposed taxes and tariffs that were not approved by parliament, which was technically illegal, and then he forced rich subjects to grant the crown loans at very low interest rates. In 1629, after parliament protested, he dismissed it and tried to rule without summoning it again. He was able to do so until 1636, when he tried to impose a new high church religious liturgy (set of rituals) in Scotland. That prompted the Scots to openly break with the king and raise an army; to get the money to fund an English response, Charles had to summon parliament.

The result was civil war. Not only were the Scots well trained and organized, when parliament met it swiftly turned on Charles, declaring his various laws and acts illegal and dismissing his ministers, an act remembered as “The Grand Remonstrance.” Parliament also refused to leave, staying in session for years (it was called “the long parliament” as a result). Meanwhile, a huge Catholic uprising took place in Ireland and thousands of Protestants there were massacred. Many in parliament thought that Charles was in league with the Irish. War finally broke out in 1642, pitting the anti-royal “round-heads” (named after their bowl cuts) and their Scottish allies against the royalist “cavaliers.” In 1645, a Puritan commander named Oliver Cromwell united various parliamentary forces in the “New Model Army,” a well-disciplined fighting force whose soldiers were regularly paid and which actually paid for its supplies rather than plundering them and living off the land (as did the king’s forces). Thanks to the effectiveness of Cromwell, the New Model Army, and the financial backing of the city of London, the round-heads gained the upper hand in the war. In the end, Charles was captured, tried, and executed by parliament in 1649 as a traitor to his own kingdom.

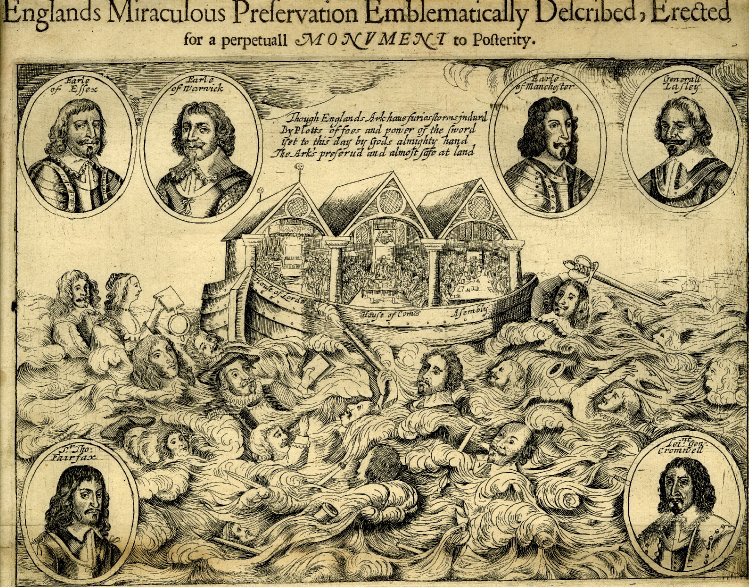

An engraving celebrating the victory of the parliamentary forces as “England’s Miraculous Preservation,” with the royalist forces drowning in the allegorical flood while the houses of parliament and the Church of England float on the ark.

During the English civil war, England went from one of the least militarized societies in Europe to one of the most militarized; one in eight English men were directly involved in fighting, and few regions in England were spared horribly bloody fighting. Simultaneously, debates arose among the round-heads concerning what kind of government they were fighting for; some, called the Levelers, argued in favor of a people’s government, a true democratic republic. The most radical were called the Diggers, who try to set up what amounts to a proto-communist society in which goods and land were held in common. Those more radical elements were ultimately defeated by the army, but the language they use in discussing justice and good government survived to inspire later debates, ultimately informing the concept of modern democracy itself.

Thanks in large part to the ongoing political debates of the period, the Civil War resulted in an explosion of print in England. Various factions attempted to impose and maintain censorship, but they were largely unsuccessful due to the political fragmentation of the period. Instead, there was an enormous growth of political debate in the form of printed pamphlets; there were over 2,000 political pamphlets published in 1642 alone. Ordinary people had begun in earnest to participate in political dialog, another pattern associated with modern politics.

After the execution of the king in 1649, England became a (technically republican) dictatorship under Cromwell, who assumed the title of Lord Protector in 1649. He ruled England for ten years, carrying out an incredibly bloody invasion of Ireland that is still remembered with bitterness today, and ruling through his control of the army. Following his death in 1658, parliament decided to reinstate the monarchy and the official power of the Church of England (which took until 1660 to happen), essentially because there was a lack of consensus about what could be done otherwise. None of the initial problems that brought about the civil wars in the first place were resolved, and Cromwell himself had ended up being as authoritarian and autocratic as Charles had been.

The Glorious Revolution

Thus, in 1660, Charles II (r. 1660 – 1685), the son of the executed Charles I, took the throne. He was a cousin of Louis XIV of France and, like his father, tried to adopt the trappings of absolutism even though he recognized that he could never achieve a Louis-XIV-like rule (nor did he try to dismiss parliament). Various conspiracy theories surrounded him, especially ones that claimed he was a secret Catholic; as it turns out, he had drawn up a secret agreement with Louis XIV to re-Catholicize England if he could, and he proclaimed his Catholicism on his deathbed. A crisis occurred late in his reign when a parliamentary faction called the Whigs tried to exclude his younger brother, James II, from being eligible for the throne because he was openly Catholic. They were ultimately beaten (legally) by a rival faction, the Tories, that supported the notion of the divine right of kings and of hereditary succession.

When James II (r. 1685 – 1688) took the throne, however, even his former supporters the Tories were alarmed when he started appointing Catholics to positions of power, against the laws in place that required all lawmakers and officials to be Anglicans. In 1688, James’s wife had a son, which thus threatened that a Catholic monarchy might remain for the foreseeable future. A conspiracy of English lawmakers thus invited William of Orange, a Dutch military leader and lawmaker in the Dutch Republic, to lead a force against James. William was married to Mary, the Protestant daughter of James II, and thus parliament hoped that any threat of a Catholic monarchy would be permanently defeated by his intervention. William arrived and the English army defected to him, forcing James to flee with his family to France. This series of events became known as the Glorious Revolution – “glorious” because it was bloodless and resulted in a political settlement that finally ended the better part of a century of conflict.

William and his English wife Mary were appointed as co-rulers by parliament and they agreed to abide by a new Bill of Rights. The result was Europe’s first constitutional monarchy: a government led by a king or queen, but one in which lawmaking was controlled by a parliament and all citizens were held accountable to the same set of laws. Even as absolutism became the predominant mode of politics on the continent, Britain set forth on a different, and opposing, political trajectory.

Great Britain After the Glorious Revolution

One unexpected benefit to constitutional monarchy was that British elites, through parliament, no longer opposed the royal government but instead became the government. After the Glorious Revolution, lawmakers in England felt secure enough from royal attempts to seize power unlawfully that they were willing to increase the size and power of government and to levy new taxes. Thus, the English state grew very quickly, whereas it had been its small size and the intransigence of earlier generations of members of parliament in raising taxes that had been behind the conflicts between king and parliament for most of the seventeenth century.

The English state could grow because parliament was willing to make it grow after 1688. It did grow because of war. William of Orange had already been at war with Louis XIV before he came to England, and once he was king Britain went to war with France in 1690 over colonial conflicts and because of Louis’s constant attempts to seize territory in the continent. The result was over twenty years of constant warfare, from 1690 – 1714.

To raise money for those wars, private bankers founded the Bank of England in 1694. While it was not created by the British government itself, the Bank of England soon became the official banking institution of the state. This was a momentous event because it allowed the government to manage state debt effectively. The Bank issued bonds that paid a reasonable amount of interest, and the British government stood behind those bonds. Thus, individual investors were guaranteed to make money and the state could finance its wars through carefully regulated sales of bonds. In contrast, Louis XIV financially devastated the French government with his wars, despite the efforts of his Intendants and other royal officials to squeeze every drop of tax revenue they could out of the huge and prosperous kingdom. Britain, meanwhile, remained financially solvent even as their wars against France grew larger every year. Ultimately, this would see the transformation of Britain from secondary political power to France’s single most important rival in the eighteenth century.

The Overall Effects of Absolutism

While Britain was thus the outstanding exception to the general pattern of absolutism, the growth in its state was comparable to the growth among its absolutist rivals. As an aggregate, the states of Europe were transformed by absolutist trends. Some of those can be captured in statistics: royal governments grew roughly 400% in size (i.e. in terms of the number of officials they employed and the tax revenues they collected) over the course of the seventeenth century, and standing armies went from around 20,000 men during the sixteenth century to well over 150,000 by the late seventeenth century.

Armies were not just larger – they were better-disciplined, trained, and “standardized.” For the first time, soldiers were issued standard uniforms. Warfare, while still bloody, was nowhere near as savage and chaotic as it had been during the wars of religion, thanks in large part to the fact that it was now waged by professional soldiers answering to noble officers, rather than mercenaries simply unleashed against an enemy and told to live off of the land (i.e. the peasants) while they did so. Officers on opposing sides often considered themselves to be part of a kind of extended family; a captured officer could expect to be treated as a respected peer by his “enemies” until his own side paid his ransom.

What united such disparate examples of absolutism as France and Prussia was a shared concept of royal authority. The theory of absolutism was that the king was above the nobles and not answerable to anyone in his kingdom, but he owed his subjects a kind of benevolent protection and oversight. “Arbitrary” power was not the point: the power exercised by the monarch was supposed to be for the good of the kingdom – this was known as raison d’etat, right or reason of the state. Practically speaking, this meant that the whole range of traditional rights, especially those of the nobles and the cities, had to be respected. Louis XIV famously claimed that “L’etat, c’est moi” – I am the state. His point was that there was no distinction between his own identity and the government of France itself, and his actions were by definition for the good of France (which was not always true from an objective standpoint, as was starkly demonstrated in his wars).

Those who lost out in absolutism were the peasants: especially in Central and Eastern Europe, what freedoms peasants had enjoyed before about 1650 increasingly vanished as the newly absolutist monarchs struck deals with their nobility that ratified the latter’s right to completely control the peasantry. Serfdom, already in place in much of the east, was hardened in the seventeenth century, and the free labor, fees, and taxes owed by peasants to their lords grew harsher (e.g., the Austrian labor obligation was known as the robot, and it could consist of up to 100 days of labor a year). The general pattern in the east was that nobles answered to increasingly powerful kings or emperors, but they were themselves “absolute” rulers of their own estates over their serfs.

The irony of the growth of both royal power and royal tax revenue was that it still could not keep up with the cost of war. Military expenditures were enormous; in a state like France the military took up 50% of state revenues during peacetime, and 80% or more during war (which was frequent). Thus, monarchs granted monopolies on products and then taxed them, and they frequently sold noble titles and state offices to the highest bidder (the queen of Sweden doubled the number of noble families in ten years). They relentlessly taxed the peasantry as well: royal taxes doubled in France between 1630 – 1650, and the concomitant peasant uprisings were ruthlessly suppressed.

One aspect of the hardening of social hierarchies, necessitated in part by the great legal benefits enjoyed by members of the nobility in the absolutist system, was that the rights and privileges of nobility were codified into clear laws for the first time. Most absolutist states created “tables of ranks” that specified exactly where nobles stood vis-à-vis one another as well as the monarch and “princes of the blood.” Louis XIV of France had a branch of the royal government devoted entirely to verifying claims of nobility and stripping noble titles from those without adequate proof.

Conclusion

The process by which states went from decentralized and fairly loosely organized to “absolutist” was a long one. Numerous aspects of government even in the late eighteenth century remained strikingly “medieval” in some ways, such as the fact that laws were different from town to town and region to region based on the accumulation of various royal grants and traditional rights over the centuries. That being noted, there is no question that things had changed significantly over the course of the seventeenth century: governments were bigger, better organized, and more explicitly hierarchical in organization.

Image Citations (Wikimedia Commons):

Cardinal Richelieu – Public Domain

Hall of Mirrors – Jorge Láscar

Louis XIV – Public Domain

Prussia – Public Domain

English Civil War Engraving – Public Domain