11.8: Supporting Dance

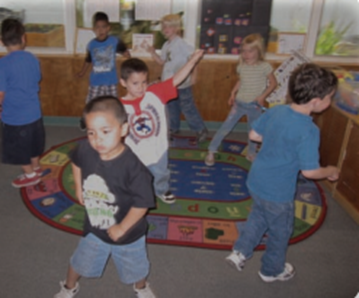

Dance and movement are an inherent part of life and are as natural as breathing. Dance is an elemental human experience and a means of expression. It begins before words are formed, and it is innate in children before they use language to communicate. It is a means of self-expression and can take on endless forms. Movement is a natural human response when thoughts or emotions are too overwhelming or cannot be expressed in words.

Dance

1.0 Notice, Respond, and Engage

| At around 48 months of age | At around 60 months of age |

| 1.1 Engage in dance movements. | 1.1 Further engage and participate in dance movements. |

| 1.2 Begin to understand and use vocabulary related to dance. | 1.2 Connect dance terminology with demonstrated steps. |

| 1.3 Respond to instruction of one skill at a time during movement, such as a jump or fall. | 1.3 Use understanding of different steps and movements to create or form a dance. |

| 1.4 Explore and use different steps and movements to create or form a dance. | 1.4 Use understanding of different steps and movements to create or form a dance. |

2.0 Develop Skills in Dance

| At around 48 months of age | At around 60 months of age |

| 2.1 Begin to be aware of own body in space. | 2.1 Continue to develop awareness of body in space. |

| 2.2 Begin to be aware of other people in dance or when moving in space. | 2.2 Show advanced awareness and coordination of movement with other people in dance or when moving in space. |

| 2.3 Begin to respond to tempo and timing through movement. | 2.3 Demonstrating some advanced skills in responding to tempo and timing through movement. |

3.0 Create, Invent, and Express Through Dance

| At around 48 months of age | At around 60 months of age |

| 3.1 Begin to act out and dramatize through music and movement patterns. | 3.1 Extend understanding and skills for acting out and dramatizing through music and movement patterns. |

| 3.2 Invent dance movements. | 3.2 Invent and recreate dance movements. |

| 3.3 Improvise simple dances that have a beginning and an end. | 3.3 Improvise more complex dances that have a beginning, middle, and an end. |

| 3.4 Communicate feelings spontaneously through dance and begin to express simple feelings intentionally through dance when prompted by adults. | 3.4 Communicate and express feelings intentionally through dance. |

There are many ways to describe each dance element. Teachers and children can add their ideas to this chart.

Table 11.5: Elements of Dance

| Body | Space | Time | Energy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Body parts: Head, torso, shoulders, hips, legs, feet

Body Actions: Nonlocomotor Stretch, bend, twist, circle, rise, fall Swing, sway, shake, suspend, collapse (qualities of movement) Locomotor Walk, run, leap, hop, jump, gallop, skip, slide |

Size: Big, little

Level: High, medium, low Place: On the spot (personal space), through the space (general space) Direction: forward, backward, sideways, turning Focus: Direction of gaze of facing Pathway: Curved, straight Relationships: In front of, behind, over, under, beside |

Beat: Underlying pulse

Tempo: Fast, slow Accent: Force Duration: Long, short Pattern: A combination of these elements of time produces a rhythmic pattern |

Attack: Sharp, smooth (qualities of movement)

Weight: Heavy, light Strength: Tight, loose Flow: Free-flowing, bound, balanced, neutral |

Teachers can support children’s development of the dance foundations with the following:

- Help children to become enthusiastic participants in learning dance.

- Warm up! Even though preschool bodies are much more resilient than adult bodies, they should still be gradually prepared for any vigorous activities.

- Use play with games that require dance movements and cooperation.

- Be aware of cultural norms that may influence children’s participation.

- Create environments and routines conducive to movement experiences.

- Consider the space, music, costumes, and props you provide.

- Establish spatial boundaries to ensure children have personal space when engaging in movement and dancing.

- Use children’s prior knowledge.

- Structure learning activities so children are active participants.

- Introduce the learning of a dance skill by using imagery.

- Draw on children’s interests in dance making.

- Plan movement activities appropriate for various developmental stages and skill levels.

- Incorporate dances that can be performed without moving the entire body.

- Encourage variety in children’s movement.

- Teach rhythm using traditional movement games.

- Use the “echo” as a helpful rhythm exercise.

- Use dance to communicate feelings.

- Use movement to introduce and reinforce concepts from other domains.

- Provide opportunities for unplanned, spontaneous dancing[1]

Table 11.6: Suggested Materials for Dance

| Type of Materials | Examples of Materials |

|---|---|

| Found or Recycled Materials | Boxes, wheels, chairs, hula hoops, balloons, umbrellas, scarves, and other found objects can be used for choreographic variety. Costumes can be assembled from fabrics or donated by families or the community. |

| Basic | Open rug space; outdoor environment with defined dance space |

| Enhanced | Piano, drums, maracas, tambourines, claves, triangles, cymbals, woodblocks, or music system A local dance troupe may donate children’s costumes that are no longer used in productions. |

| Natural Environment | Palm leaves, feathers, sand, water, and sticks can be used in movement activities. |

| Adaptive Materials | If a child has a prosthesis, he or she can decide whether to dance with it on or off. If a child uses a wheelchair, props can be useful to extend what the body can do; a few possibilities are balloons tied to a stick, crepe paper streamers, and scarves. |

Research Highlight

Research supports the inclusion of dance in a preschool curriculum for a number of reasons, not the least of these being the social–emotional benefits gained from dancing at an early age.

In The Feeling of What Happens, neuroscientist Antonio Damasio describes the body as the theater for emotions and considers emotional responses to be responsible for profound changes in the body’s (and the brain’s) landscape. Damasio creates three distinct classifications for emotions based on the source of the emotion and the physical response to the emotion: primary, secondary, and background emotions. The primary emotions are the familiar emotions recognizable in preschoolers and adults alike: happiness, sadness, fear, anger, and surprise. Damasio describes secondary emotions as social emotions, such as jealousy or envy when a child is eyeing a friend’s toy or feelings of pride when accomplishing a difficult task. And of particular interest in a discussion of dance are the background emotions—much like moods. These refer to indications that a person feels down, tense, cheerful, discouraged, or calm, and others.

Background emotions do not use the differentiated repertoire of explicit facial expressions that easily define primary and social emotions; they are also richly expressed in musculoskeletal changes, for instance, in subtle body posture and overall shaping of body movement. Movement and dance are natural vehicles for expression of these emotions.[3]

Source:

A. Damasio, The Feeling of What Happens: Body and Emotion in the Making of Consciousness (New York: Harcourt Brace, 1999), 51–53.

Vignettes

Sammy, a four-year-old in Ms. Huang’s class, pulls a top hat off the hat rack and begins to perform controlled balances high on the balls of his feet. Two other children become interested in this performance, and suddenly three children are using hats as creative props to stretch high into the air, with their arms, as they rise up on their toes forming a chorus line; Sammy continues to play the lead, placing a hat on a foot and balancing on one leg like a bird; the other children imitate. The movement progresses to a balancing game, and the children occasionally tumble to the floor, giggling.

Ms. Huang observes the movement game for several minutes and notices the children have taken to making the same shape of the lifted bird leg. She recognizes the children’s imagination by commenting on their creative play with the hat; she then suggests to Sammy that he attempt to bring his leg behind him (in a pose resembling a ballet arabesque) while keeping the hat balanced on his foot. The trio becomes more focused with their balances and inventive with the shapes, moving the legs from the front to back and even experimenting with lowering the torso while lifting the leg.

Mr. Soto leads the children in a lively singing and dancing performance of Juanito (Little Johnny). The children shake and twist their bodies while clapping their hands as they sing. “Juanito cuando baila, baila, baila, baila. Juanito cuando baila, baila con el dedito, con el dedito, ito, ito. Asi baila Juanito.” (When little Johnny dances, he dances, dances. When little Johnny dances, he dances with his pinkie, with his pinkie, pinkie, pinkie. That’s how little Johnny dances.)

In the first verse, they wiggle the pinkie back and forth; in the second, they shake the foot and then wiggle the pinkie. Each time a new verse is sung, a movement is added until the children’s bodies are in motion, from head to toe!

Even Matthew, who is generally reluctant to dance, picks his knees high up and waves his arms exuberantly. Mr. Soto changes the character of the song to Mateo, and Matthew dances into the center of the circle.[4]

- Source of text in black: The California Preschool Curriculum Framework, Volume 2 by the California Department of Education is used with permission; Source of text in blue: Clint Springer; Source of foundations: The California Preschool Curriculum Framework, Volume 2 by the California Department of Education is used with permission ↵

- The California Preschool Curriculum Framework, Volume 2 by the California Department of Education is used with permission ↵

- Ibid ↵

- Ibid ↵