12.4: Introducing to the Foundations

The preschool learning foundations for History and Social Science are organized into five broad categories or strands:

- Self and Society: children’s growing ability to see themselves within the context of society

- Becoming a Preschool Community Member (Civics): becoming responsible and cooperative members of the preschool community

- Sense of Time (History): developing understanding of past and future events and their association with the present

- Sense of Place (Geography and Ecology): developing knowledge of the physical settings in which children live and how they compare with other locations

- Marketplace (Economics): developing understanding of economic concepts, including the ideas of ownership, money exchanged for goods and services, value and cost, and bartering[1]

Supporting Self and Society

An early childhood education setting acquaints young children with people who have different backgrounds, family practices, languages, cultural experiences, special needs, and abilities. In their relationships with teachers and peers, preschoolers perceive how others are similar to them and how they are different, and gradually they learn to regard these differences with interest and respect rather than wariness or doubt. This is especially likely if early childhood educators incorporate inclusive practices into the preschool environment. The relationships that young children develop with others in the preschool provide opportunities for understanding these differences in depth and in the context of the people whom the child knows well. One of the most valuable features of a thoughtfully designed early childhood program is helping young children to perceive the diversity of human characteristics as part of the richness of living and working with other people.

Young children are beginning to perceive themselves within the broader context of society in another way also. Their interest in adult social roles, occupations, and responsibilities motivates pretend play, excitement about visits to places such as a fire station or grocery store, and questions about work and its association with family roles and family income. Teachers can help young children explore these interests as children try to understand the variety of adult roles

1.0 Culture and Diversity

| At around 48 months of age | At around 60 months of age |

| 1.1 Exhibit developing cultural, ethnic, and racial identity and understand relevant language and cultural practices. Display curiosity about diversity in human characteristics and practices, but prefer those of their own group. | 1.1 Manifest stronger cultural, ethnic, and racial identity and greater familiarly with relevant language, traditions, and other practices. Show more interest in human diversity, but strongly favor characteristics of their own group. |

2.0 Relationships

| At around 48 months of age | At around 60 months of age |

| 2.1 Interact comfortably with many peers and adults; actively contribute to creating and maintaining relationships with a few significant adults and peers. | 2.1 Understand the mutual responsibilities of relationships; take initiative in developing relationships that are mutual, cooperative, and exclusive. |

3.0 Social Roles and Occupations

| At around 48 months of age | At around 60 months of age |

| 3.1 Play familiar adult social roles and occupations (such as parent, teacher, and doctor) consistent with their developing knowledge of these roles. | 3.1 Exhibit more sophisticated understanding of a broader variety of adult roles and occupations, but uncertain how work relates to income. |

Teachers can support children’s development of the self and society foundations with the following:

- Practice a reflective approach to build awareness of self and others by examining your own attitudes and values

- Maintain a healthy curiosity about the experiences of others; ask authentic questions to build understanding

- Partner with families in goal setting and program design; learn individual family values and each family’s goals for their child’s care and education

- Prepare an active learning environment that incorporates the full spectrum of the human experience including diversity of cultures, ethnicities, gender, age, abilities, socioeconomic class, and family structure

- Create an environment, both indoors and outdoors, that is inclusive, meaning every child can fully participate and engage in the learning environment regardless of gender, home language, or abilities

- Address children’s initial comments and inquiries about diversity with honest, direct communication

- Have discussions about similarities and differences

- Sing songs and share stories in different languages

- Plan meaningful and authentic celebrations with support of the children and families

- Read and talk about books that:

- Accurately represent the lives and experiences of children

- Deal with the theme of friendship and relating to others

- Include images and stories of different workers

- Develop meaningful, nurturing relationships with the children in your program

- Prepare an early learning environment and daily routine that foster peer interaction

- Support children’s development of interaction strategies and relationship building skills through:

- Modeling

- Explicit instruction during large-group times

- Coaching and providing prompts

- Offer sensitive guidance through challenges

- Facilitate positive social problem solving

- Provide children with play props for exploring occupations and work settings

- Get to know the workers in your community

- Convey respect for the roles of adults who work at home

- Highlight the roles that elders play in family life and in society

- Include the pursuit of further education among work options

- Invite family members to share their work experiences, including those that may diverge from traditional gender roles

- Talk about future career goals

- Visit community stores, businesses, and service providers to observe workers in action[2]

Vignette

“You always get to do the money,” complains Emma. Beck announces, “No, Tommy, I’m the customer. I was here first.” Ella and Maya argue about the pieces of a plastic hamburger: “You can’t have it again. It’s the only one . . . ” These and similar interactions between children have been typical in the area ever since Ms. Berta added the ”Restaurant” prop box to it.

Now Ms. Berta is struggling to figure out how to foster more cooperation among children playing in this dramatic play area. The restaurant theme is very popular, but children’s play is currently dominated by arguments over who gets to use which items from the restaurant prop box. Each child seems to be trying, independently, to hoard the most items from the box.

Ms. Berta shares her dilemma with Ms. Galyna, the school’s mentor teacher, who says she can come in for a quick visit during the next day’s play time. She follows her visit with some suggestions that help Ms. Berta rethink the area’s design for the following week

On Monday, the children entering the area are greeted by a large restaurant sign. A waist-high shelf unit defines the front of the area. On top of it sit two toy cash registers, supplied with ample paper bills, plastic coins, receipt pads, and pencils. A clear plastic jar labeled “Tips” sits in between. On a hook, hang clip-on badges: Cook, Cashier, Server, and Customer. There are several of each. The shelves under the front counter hold stacks of paper drink cups and trays. The cooking pans and utensils are clearly displayed on the area’s stove and sink shelves, as are multiples of food items and dishes in the refrigerator and cupboard. The eating table is set for customers

Ms. Berta begins play time as a restaurant customer, placing her order, asking questions of the employees, and helping the other players think about what a cook, server, or cashier in a restaurant would do. She refers them to each other with their ideas and questions, and soon they are having restaurant conversations with her and with each other “in character.”

Over the next two weeks, the group makes changes and additions to the restaurant. At a class meeting, the group votes to make it a pizza restaurant, and the teacher adds donated pizza rounds that children cover with drawn-on toppings. With Ms. Berta’s help, interested children work in pairs to write and post menus. Several small groups of children remain intensely interested in the theme, and their play in the restaurant area becomes more elaborate and content-rich. With active teacher support and modeling, friends are able to constructively solve conflicts that occur.[3]

Pause to Reflect

What are some of your own biases and “blind spots” about people whose racial or cultural backgrounds are very different from yours?

In what ways could you partner with the families to support attitudes of acceptance and inclusion?

Supporting Becoming A Preschool Community Member (Civics)

An early childhood program is a wonderful setting for learning how to get along with others and for understanding and respecting differences between people. It is also an important setting for learning about oneself as a responsible member of the group. In an early childhood education setting, young children are enlisted into responsible citizenship for the first time outside of the family, encouraged to think of themselves as sharing responsibility for keeping the room orderly, cooperating with teachers and peers, knowing what to do during group routines (e.g., circle time), cleaning up after group activities, participating in group decisions, supporting and complying with the rules of the learning community, and acting as citizens of the preschool.

Many formal and informal activities of an early childhood education setting contribute to developing the skills of preschool community membership. These include group decision making that may occur during circle time (including voicing opinions, voting on a shared decision, and accepting the judgment of the majority); resolving peer conflict and finding a fair solution; understanding the viewpoints of another with whom one disagrees; respecting differences in culture, race, or ethnicity; sharing stories about acting responsibly or helpfully and the guidance that older children can provide younger children or children with less positive experiences about being a preschool community citizen.

1.0 Skills for Democratic Participation

| At around 48 months of age | At around 60 months of age |

| 1.1 Identify as members of a group, participate willingly in group activities, and begin to understand and accept responsibility as group members, although assistance is required in coordinating personal interests with those of others. | 1.1 Become involved as responsible participants in group activities, with growing understanding of the importance of considering others’ opinions, group decision making, and respect for majority rules and the views of group members who disagree with the majority. |

2.0 Responsible Conduct

| At around 48 months of age | At around 60 months of age |

| 2.1 Strive to cooperate with group expectations to maintain adult approval and get along with others. Self-control is inconsistent, however, especially when children are frustrated or upset. | 2.1 Exhibit responsible conduct more reliably as children develop self-esteem (and adult approval) from being responsible group members. May also manage others’ behavior to ensure that others also fit in with group expectations. |

3.0 Fairness and Respect for Other People

| At around 48 months of age | At around 60 months of age |

| 3.1 Respond to the feelings and needs or others with simple forms of assistance, sharing, and turn-taking. Understand the importance of rules that protect fairness and maintain order. | 3.1 Pay attention to others’ feelings, more likely to provide assistance, and try to coordinate personal desires with those of other children in mutually satisfactory ways. Actively support rules that protect fairness to others. |

4.0 Conflict Resolution

| At around 48 months of age | At around 60 months of age |

| 4.1 Can use simple bargaining strategies and seek adult assistance when in conflict with other children or adults, although frustration, distress, or aggression also occurs. | 4.1 More capable of negotiating, compromising, and finding cooperative means of resolving conflict with peers or adults, although verbal aggression may also result. |

Teachers can support children’s development of the civics foundations with the following:

- Share control of the preschool environment with children

- Create community rules with children’s input and plan opportunities to continue discussing them with small- and large-group meetings

- Promote a sense of connection and community by using terms such as “we” and “our” when speaking with children and adults

- Incorporate class meetings into the daily routine of older preschool children

- Support freedom of thought and speech in individual investigations, as well as in planned group experiences

- Generate community rules and expectations to protect the rights of each individual and to create a community of trust and security

- Engage children in community brainstorming and problem solving

- Make group decisions when appropriate

- Acknowledge emotions related to group brainstorming and decision making

- Model the skills and behavior you want children to exhibit

- Use guidance to redirect children to more appropriate actions and behavior by using positive descriptions of what you expect children to do

- Help children remember and meet community generated rules and expectations by providing both visual and auditory cues and prompts

- Reinforce the positive actions of children by using descriptive language, emphasizing the positive impact of a child’s actions on others

- Facilitate problem solving

- Create an inclusive environment that values and encourages the participation of children from all cultural and linguistic backgrounds as well as children with special needs

- Set the tone for responsible conduct by creating a high-quality learning environment and thoughtfully scheduled daily routine

- Assign tasks for community care, such as watering plants, feeding program pets, or helping to prepare snacks, to help children practice responsibility

- Discuss the “whys” of fairness and respect

- Teach social skills, such as patience and generosity, by using social stories and role-play experiences

- Intervene and address negative interactions immediately

Prevent conflicts by limiting program transitions and minimizing waiting time - Provide children with a calm presence in conflict situations

- Support children’s conflict resolution by

using descriptive language to help children make sense of conflict

prompting children with open-ended questions and statements

facilitating, rather than dictating, the solution process - Create and refer children to problem-solving kits with visual cues

- Use and discuss books that have storylines around relationships, community, and conflict

- Use “persona dolls” or puppets and social stories to promote skill development and perspective taking[4]

Vignettes

The children gather for circle time, and after the group’s gathering song, Ms. Anya begins dramatically. “Today I am going to tell you a story about something that just happened in our room.

At the beginning of playtime today, two of our friends, Julia and Javier told me their plan was to work with the medical kits in the house area. They were going to use the stethoscopes, bandages, and all the other medical tools to take care of the babies. I told them I would plan to visit later to see if their patients were feeling better.

A few minutes later, Julia and Javier hurried over to tell me that all the babies were missing. They had looked all over the clinic, and had found no babies! Where do you think they looked?”

The children in the group call out their ideas about all the places the children could have looked. Ms. Anya continues, “You are right. They looked in all those places. No babies. So what did they do next?” Many children around the circle who are now recalling the incident call out, “They asked us to help!” “That’s right,” affirms Ms. Anya. “They know what good problem solvers you are and how good you are at teamwork, so they asked you. Pretty soon you gave them lots of helpful suggestions of places to look. And did they find the babies?” “Yes!” the children call out. “And where were the baby dolls, Julia and Javier?” “They were out on the porch!” the children respond, laughing.

Ms. Anya concludes the story by repeating, “Yes, you are right. The dolls were out on the porch drying after yesterday’s bath. Thank you all for helping us solve the mystery of the missing baby dolls.”[5]

Pause to Reflect

What are some ways educators can be a good example for children to follow as they learn skills for being members of a community?

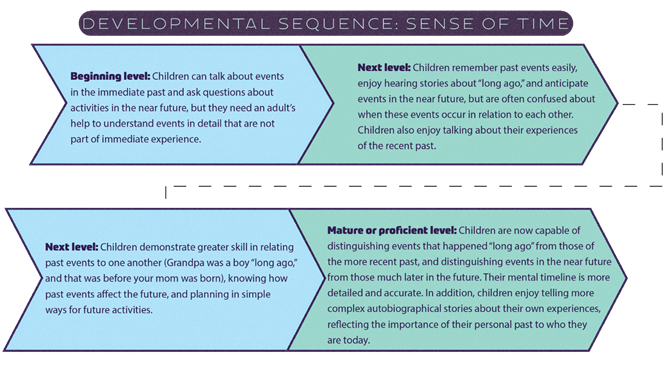

Supporting Sense of Time (History)

One of our unique human characteristics is the ability to think of ourselves in relation to past events and to anticipate the future. The ability to see oneself in time enables us to derive lessons from past experiences, understand how we are affected by historical events, and plan for the immediate future (such as preparing a meal) or the long-term (such as obtaining an education). The ability to see oneself in time is also the basis for perceiving one’s own growth and development, and the expectation of future changes in one’s life.

The preschool years are a period of major advances in young children’s understanding of past, present, and future events and how they are interconnected. Yet their ability to understand these interconnections is limited and fragile. Young preschoolers have a strong interest in past events but perceive them as ‟islands in time” that are not well connected to other past events. As they learn more about events of the past, and with the help of adults, children develop a mental timeline in which these events can be placed and related to each other. This is a process that begins during the preschool years and will continue throughout childhood and adolescence.

A thoughtfully designed early childhood program includes many activities that help young children develop a sense of the past and future. The activities may include conversations about a child’s memorable experiences, discussions of a group activity that occurred yesterday, stories about historical events, circle-time activities in anticipation of a field trip tomorrow, and picture boards with the daily schedule in which special events can be distinguished from what normally happens. In these and other ways, teachers help young children construct their own mental timelines.

1.0 Understanding Past Events

| At around 48 months of age | At around 60 months of age |

| 1.1 Recall past experiences easily and enjoy hearing stories about the past, but require adult help to determine when past events occurred in relation to each other and to connect them with current experience. | 1.1 Show improving ability to relate past events to other past events and current experiences, although adult assistance continues to be important. |

2.0 Anticipating and Planning Future Events

| At around 48 months of age | At around 60 months of age |

| 2.1 Anticipate events in familiar situations in the near future, with adult assistance. | 2.1 Distinguish when future events will happen, plan for them, and make choices (with adult assistance) that anticipate future needs. |

3.0 Personal History

| At around 48 months of age | At around 60 months of age |

| 3.1 Proudly display developing skills to attract adult attention and share simple accounts about recent experiences. | 3.1 Compare current abilities with skills at a younger age and share more detailed autobiographical stories about recent experiences. |

4.0 Historical Changes in People and the World

| At around 48 months of age | At around 60 months of age |

| 4.1 Easily distinguish older family members from younger ones (and other people) and events in the recent past from those that happened “long ago,” although do not readily sequence historical events on a timeline. | 4.1 Develop an interest in family history (e.g., when family members were children) as well as events of “long ago,” and begin to understand when these events occurred in relation to each other. |

Teachers can support children’s development of the history foundations with the following:

- Use predictable routines to facilitate children’s sense of time

- Incorporate time words into conversation, such as before, after, yesterday, first, next, and later

- Create opportunities to talk with children about meaningful experiences and build connections between current and past events and to anticipate future events

- Extend and expand on children’s narrative descriptions with language relating to time

- Share your memories of the children’s abilities over time

- Ask questions to increase children’s recollections of events

- Document and display children’s work at their eye level to encourage recall and reflection

- Sing songs, recite poetry, and read books that involve sequencing

- Promote planning as children engage in child-initiated projects

- Acknowledge birthdays, with sensitivity to family preferences

- Provide activities that invite personal reflection

- Make use of children’s stories that explore growth and individual change

- Utilize familiar resources, such as parents, grandparents, family members, close friends and community members, to share their own childhood experiences

- Read children’s stories about different places and times to expand children’s perspective

- Expose children to the arts

- Observe changes in animals, plants, and the outdoors

- Record significant events on a large calendar to create a program history

- Provide children with hands-on experiences with concrete artifacts and historical objects (e.g., toys, utensils, tools)[6]

Vignettes

At outdoor play time, Mateo hurries over to a large tree limb lying at the edge of the playground. “Look what happened!” he exclaims. “Yeah,” agrees Luis, who had joined him, “the wind did it. It crashed down our big tree, too, right into the street. Some guys are coming to saw it up.” Luis pauses. “My grandma said that tree was really old.” Ms. Sofia, who has followed them to the area, joins the conversation. “Your grandma told me about that when she came with you this morning. It’s a big surprise when a tree that was there just yesterday suddenly isn’t there anymore today, especially when it had been growing there for a long, long time. Things like that can happen fast. What do you think will be different when you get home this afternoon?”

For today’s circle time, Ms. Robin has prepared a two-column chart with the headings: “When I was a baby, I couldn’t . . .” and “Now I can . . .” She reads the first phrase and asks the group to think of things they were not able to do as babies. As children share their ideas, including, “I couldn’t walk; I couldn’t ride a trike, I couldn’t eat apples . . .” she lists them in the first column. When they finish, she reads all the ideas aloud to the group.

Ms. Robin then points to the phrase, “Now I can . . .” and again asks for children’s ideas. After they finish sharing, she reads aloud the second list. As she points to each list, she comments to the group enthusiastically, “Look how many things you couldn’t do when you were a baby! Look how many things you can do now! You’ve grown so much!”

Nico looks through the familiar homemade, photo-illustrated book titled Teacher Jen’s Broken Ankle that is displayed on the reading area book rack. “My papa fell and broke his arm when he was a little boy,” he tells Ms. Jen. She asks him how it happened, and he tells her the story his papa has told him. Ms. Jen wonders with Nico whether his papa had to wear a cast on his arm while it was healing. Nico says he thinks so, because he remembers that Papa was supposed to keep his arm dry for a long time. He then asks Ms. Jen to show him again the ankle cast she wore while her leg was healing. She keeps the two halv[7]es of her bright pink cast in the “Hospital” prop box that teachers use in the dramatic play area when children’s play signals interest in medical themes.

Pause to Reflect

How might you want to partner with families to make the preschool environment reflective of their diverse family stories?

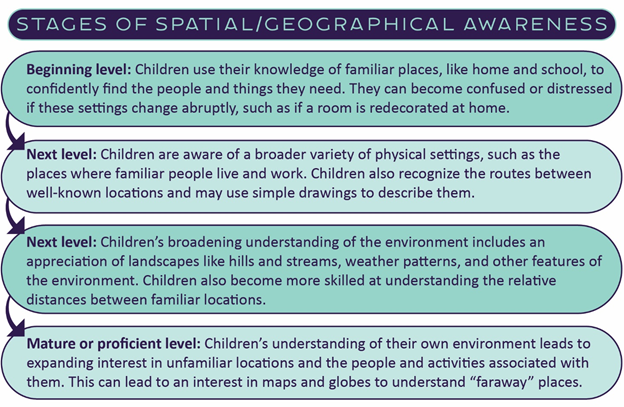

Supporting Sense of Place (Geography and Ecology)

Each person has a sense of the places to which they belong: home, workplace, school, and other locations that are familiar and meaningful. Young children experience this sense of place strongly because familiar locations are associated with important people who constitute the child’s environment of relationships. Locations are important because of the people with whom they are associated: home with family members, preschool with teachers and peers. Preschoolers also experience a sense of place because of the sensory experiences associated with each location: the familiar smells, sounds, and sometimes temperatures and tastes combine with familiar scenes to create for young children a sense of belonging.

Developing a sense of place also derives from how young children interact with aspects of that physical location. Preschool children relate with their environments as they work with materials; rearrange tables, chairs, and other furniture; create maps to familiar locations; travel regularly from one setting to another; and work in other ways with their environments. Young children also interact with their environments as they learn to care for them. Young children’s natural interest in living things engages their interest in caring for plants and animals, concern for the effects of pollution and litter on the natural environment, and later, taking an active role in putting away trash and recycling used items.

These interests present many opportunities to the early childhood educator. Young children can be engaged in activities that encourage their understanding of the environments in which they live, whether they involve creating drawings and maps of familiar locations, talking about how to care for the natural world, discussing the different environments in which people live worldwide, or taking a trip to a marshland or a farm.

1.0 Navigating Familiar Locations

| At around 48 months of age | At around 60 months of age |

| 1.1 Identify the characteristics of familiar locations such as home and school, describe objects and activities associated with each, recognize the routes between them, and begin using simple directional language (with various degrees of accuracy). | 1.1 Comprehend larger familiar locations, such as the characteristics of their community and region (including hills and streams, weather, common activities) and the distances between familiar locations (such as between home and school), and compare their home community with those of others. |

2.0 Caring for the Natural World

| At around 48 months of age | At around 60 months of age |

| 2.1 Show an interest in nature (including animals, plants, and weather) especially as children have direct experiences with them. Begin to understand human interactions with the environment (such as pollution in a lake or stream) and the importance of taking care of plants and animals. | 2.1 Show an interest in a wider range of natural phenomena, including those not directly experienced (such as snow for a child living in Southern California), and are more concerned about caring for the natural world and the positive and negative impacts of people on the natural world (e.g., recycling, putting trash in trash cans). |

3.0 Understanding the Physical World Through Drawings and Maps

| At around 48 months of age | At around 60 months of age |

| 3.1 Can use drawings, globes, and maps to refer to the physical world, although often unclear on the use of map symbols. | 3.1 Create their own drawings, maps, and models; are more skilled at using globes, maps, and map symbols; and use maps for basic problem solving (such as locating objects) with adult guidance. |

Teachers can support children’s development of the geography and ecology foundations with the following:

- Supply open-ended materials in the indoor and outdoor early learning environment to promote exploration of spatial relationships

- Set aside time for outdoor explorations each day

- Provide children with sensory experiences, especially those with sand and water

- Describe your own actions as you travel between locations

- Play games about how to get from here to there

- Engage children in conversation about how they travel to and from preschool each day

- Take walks through familiar locations and neighboring areas

- Talk about the here and now as well as encouraging later reflection

- Locate and explore local landmarks

- Promote children’s understanding of weather and its impact on their day-to-day experiences

- Comment on weather patterns and invite children to share their observations

- Read aloud books and engage children in storytelling related to

- navigating familiar locations and daily routines

- investigating the earth and its attributes

- Integrate living things into the indoor learning environment

- Observe life in its natural setting

- Compare and contrast living and nonliving things

- Model respect and care for the natural world

- Use descriptive language to talk about the earth and its features

- Teach young children easy ways to conserve the earth’s resources

- Grow a garden in the program’s outdoor space

- Eat fresh produce at snack time and obtain food directly from a local gardener, farmers market, or food vendor when possible

- Engage children in conversations about maps, provide map-making materials, incorporate maps into dramatic play, use maps when planning outings, and make a mpa of the classroom/building and outdoor space

- Supply the learning environment with a variety of blocks and other open-ended materials to support the symbolic representation of the world the children see and experience each day

- Play board games that use trails and pathways

- View locations from different physical perspectives

- Prepare a treasure hunt[8]

Vignettes

Michael sits down with his peers and Mr. Sean at the snack table. “There was a huge dump truck going down my street today,” he tells everyone. Mr. Sean asks him what was in the truck. “Rocks and big sidewalk pieces,” replies Michael. “I know that,” adds Rio. “It’s by my house. Papa says they’re digging up the street for water pipes.” Several other children nod and agree that they know where that is and they have gone by it, too. Mr. Sean tells the children that the construction site they are talking about is just around the corner and down one block from their preschool. “Would you like to take a walk together to watch them work?” he asks. “It sounds like a big and exciting construction project is happening in our neighborhood.”

“I like this place,” shares Maya as she looks around the small reading area. “What do you like about it?” asks Ms. Nicole. “I like the green. It’s like un bosque.” Yes, agrees Ms. Nicole. The green plants do make it seem like a forest.”

This is the castle for the princess and her friends,” explains Grace to Tanya as she describes her unit block structure. “Here’s the bedroom over here, and the tower over there.”

Ms. Julia, sitting in the block area to observe children’s play, responds, “It looks like a very long way from the bedroom to the tower. Do the princess and her friends ever get lost in the castle?” “Well . . . sometimes they do,” replies Grace. “I wonder if we could draw something to help them find their way,” suggests Ms. Julia. “Like a map!” exclaims Tanya to Grace.

Ms. Julia offers to bring the clipboards, equipped with paper and pencils, from the art area. She takes one and begins describing her drawing plan. “First I’m going to draw a square for the bedroom in this corner . . . ” The girls begin by imitating her technique and soon are exchanging ideas with each other as they draw their versions of the castle. When they are finished, Ms. Julia asks questions about the parts of their castle maps and offers to label them. When the maps are finished, labeled, and signed, Ms. Julia asks the girls’ permission to display them on the block area wall.[9]

Pause to Reflect

What would be ways you would be comfortable bringing caring for the natural world into your own classroom? What might some things to try beyond that?

Supporting Marketplace (Economics)

Young children’s interest in adult roles and occupations extends to the economy. Preschoolers know that adults have jobs, and they observe that money is used to purchase items and services, but the connections between work, money, and purchasing are unclear to them. This does not stop them, however, from enacting these processes in their pretend play and showing great interest in the economic transactions they observe (such as a trip to the bank with a parent).

Moreover, young children are also active as consumers, seeking to persuade their families to purchase toys or access to activities that they desire, sometimes hearing adult concerns about cost or affordability in response. On occasion, they also learn about economic differences between people and families, such as when a parent is unemployed or when families are living in poverty. All of these activities convince them that the economy, while abstract to them, is important.

A carefully designed early childhood education setting provides many opportunities for young children to explore these ideas through play, conversation, and the creation of economic items to buy, sell, or exchange.

1.0 Exchange

|

At around 48 months of age |

At around 60 months of age |

| 1.1 Understand ownership, limited supply, what stores do, give-and-take, and payment of money to sellers. Show interest in money and its function, but still figuring out the relative value of coins. | 1.1 Understand more complex economic concepts (e.g., bartering; more money is needed for things of greater value; if more people want something, more will be sold). |

Teachers can support children’s development of the economics foundations with the following:

- Introduce economic concepts (e.g., production, exchange, consumption) through children’s books

- Provide open-ended materials to support children’s spontaneous investigations of business and the economy

- Offer dramatic play experiences that allow children to explore economic concepts

- Explore alongside children, expanding on their initiative

- Draw attention to trends of consumption in the preschool setting

- Discuss wants and needs with children and allow children to help make economic decisions

- Explore all forms of exchange

- Visit local businesses

- Create an opportunity for children to make and sell their own product; discuss how the money made will be spent[10]

Vignettes

Ms. Jen settles into the reading chair to begin large group story time. She holds a tall empty jar, a small cloth bag, and a book.

“Today I brought something with me to help me tell a story,” she begins. Then she holds up the small drawstring bag and shakes it. “Money!” call out the children. “Yes, it is money. My little bag is full of coins: nickels, dimes and quarters,” she says, pulling out one of each. “This book is all about a family who collects coins and saves them in a jar that looks a lot like this one. It’s called A Chair for My Mother, and Vera B. Williams is the author. She wrote the words. She is also the illustrator, which means she painted the pictures.”

As Ms. Jen reads the book, she stops frequently to converse with children about what is happening in the story. “The mother in this story works as a server in a restaurant. That’s how she earns money to buy the things her family needs.” After reading the page that describes the “tips” that Mother brings home and puts into the jar, Ms. Jen asks the group if anyone they know gets tips at work. After explaining the idea, she pours the coins from her small bag into the tall jar she has brought as a story prop.

When she reads the pages about the family’s moving day, when all their relatives and neighbors brought things they needed to replace the ones lost in the fire, Ms. Jen talks about how people don’t always buy all the things they have. Sometimes people receive gifts and things that others share with them.

As each economic concept is introduced in the book, Ms. Jen pauses to draw attention to it, while maintaining the flow of the story. At the end, she holds up the jar of coins and asks the group how long they think it took for Josephine’s family to collect enough coins to buy the chair. She responds to their comments, listening as they share their own related ideas. She concludes by telling them that the book will be in the reading area tomorrow for them to enjoy again.[11]

Pause to Reflect

What resources are in your neighborhood that a preschool teacher could use to introduce children to the community’s economic life?

Engaging Families

Teachers can make the following suggestions to families to facilitate their support of history and social science

- Encourage families to tell stories and sing songs to their child about their home culture

- Remind families that they are the child’s most influential models.

- Support families to help their child develop strong, warm relationships with adults and children among their family and friends.

- Suggest ways that family members can talk with their child about the daily work they do.

- Suggest that adults find household projects to work on with their child.

- Remind adults to notice and recognize times when their child is being cooperative and responsible.

- Encourage adults to talk with their child about respect and fairness.

- Work with adult family members as they establish some simple, age-appropriate rules to be followed at home and help children understand that there is a reason for each rule.

- Share ways to establish some dependable family rituals and routines.

- Remind families to discuss family plans and events with children before they occur.

- Share with family adults the importance of recounting past shared events with their children. Suggest that they use storytelling to help children remember the sequence and details of both everyday and special experiences.

- Suggest that families find a special place for items that document children’s growth.

- Encourage adult family members to tell children stories about their family’s history.

- Suggest that they look for maps in places where their family goes.

- Suggest taking different routes when going to familiar places.

- Encourage families to talk about nature (i.e., weather, seasons, plants, animals, and so on) with their child.

- Encourage families to have conversations about ways they can help the earth (reduce waste, conserve natural resources, compost, etc.)

- Suggest that adult family members share with their child elements of the natural world they especially enjoy.

- Encourage families to talk with their child about the connection between cost and decisions to buy items and services.

- Assure families that it is fine to have conversations about “wants” and “needs.”

- Suggest that families show their child some alternative ways to acquire things the family needs or wants, as well as ways to help meet the needs of others.

- Encourage families to begin to share with preschool children their own values about money.

- Prepare yourselves, as early care and education professionals, to play an active role in supporting families facing personal economic crises. Educate yourselves about available community services and, when possible, help families to obtain access to them.[12]

- The California Preschool Curriculum Framework, Volume 3 by the California Department of Education is used with permission ↵

- Ibid ↵

- Ibid ↵

- The California Preschool Curriculum Framework, Volume 3 by the California Department of Education is used with permission; The California Preschool Learning Foundations (Volume 1) by the California Department of Education is used with permission ↵

- The California Preschool Curriculum Framework, Volume 3 by the California Department of Education is used with permission ↵

- The California Preschool Curriculum Framework, Volume 3 by the California Department of Education is used with permission; The California Preschool Learning Foundations (Volume 1) by the California Department of Education is used with permission ↵

- The California Preschool Curriculum Framework, Volume 3 by the California Department of Education is used with permission ↵

- The California Preschool Curriculum Framework, Volume 3 by the California Department of Education is used with permission; The California Preschool Learning Foundations (Volume 1) by the California Department of Education is used with permission ↵

- The California Preschool Curriculum Framework, Volume 3 by the California Department of Education is used with permission ↵

- The California Preschool Curriculum Framework, Volume 3 by the California Department of Education is used with permission; The California Preschool Learning Foundations (Volume 1) by the California Department of Education is used with permission ↵

- The California Preschool Curriculum Framework, Volume 3 by the California Department of Education is used with permission ↵

- Ibid ↵