15.8: Developmentally Appropriate Planning for Infants and Toddlers – The Infant and Toddler Learning and Development Foundations

We started the chapter by looking at what infants and toddlers are like. The foundations, which describe competencies—knowledge and skills—that all young children typically learn with appropriate support, provide guidance on how to plan what is developmentally appropriate for infants and toddlers. They also present infant/toddler learning and development as an integrated process that includes social–emotional development, language development, cognitive development, and perceptual and motor development. The foundations give a comprehensive view of what infants and toddlers learn through child-initiated exploration and discovery, teacher-facilitated experiences, and planned environments, offering rich background information for teachers to consider as they plan for children.

The foundations identify key areas of learning and development. While moving in the direction identified by each foundation, every child will progress along a unique path that reflects his or her individuality and cultural and linguistic experiences. The foundations help teachers understand children’s learning and can give focus to intentional teaching.[1]

Social–Emotional Development

Social–emotional development includes the child’s experience, expression, and management of emotions and the ability to establish positive and rewarding relationships with others. It encompasses both intra- and interpersonal processes.

Guiding principles of the social-emotional curriculum include:

- Learn from the family about the child’s social–emotional development

- Place relationships at the center of curriculum planning

- Read and respond to children’s emotional cues

- Attend to the environment’s impact on children’s social– emotional development

- Understand and respect individuality

The environment should:

- Be positive and allow children to explore freely, while often hearing “yes” and seldom hearing “no”

- Provide materials that support relationships and the development of social understanding

- Provide materials that relate to feelings and emotional expression

- Be arranged to support peer interactions and relationships

Caregivers should:

- Offer learning opportunities through caregiving routines

- Learn about temperament

- Pay attention to feelings and emotional responses

- Support and respect the child’s relationship with his or her family

- Support relationships and interactions among the children in the program

- Model responsive and respectful interactions and behavior

- Respect children’s interests

- Support children’s regulation of emotions

- Demonstrate acceptance for all of the feelings children express[2]

Vignette

Anita is holding six-month-old Jed on her lap. Jed is the first child to arrive in Anita’s family child care home each day. They have a few quiet minutes together before the other children begin to arrive. Anita has noticed that Jed often demonstrates excitement when watching the older children. He kicks his legs and puffs his breath when he sees Carlo and his mother enter the playroom. Miss Anita turns so that Jed can easily see Carlo and she says softly to Jed, “Here is Carlo, coming to play. He made you laugh yesterday, didn’t he?” Anita smiles and greets Carlo and his mother, and then she says, “Carlo, Jed is so happy to see you. Do you see how he kicks his legs and waves his arms? Would you like to say hello?” When Carlo approaches, Anita says to Jed, “Here is Carlo, coming to say hello.” The boys gaze at each other quietly for a moment. Anita is attentive and silent. Then Carlo makes a silly face and dances, and Jed lets out a little giggle. Carlo’s mother, who is several months pregnant, shares a smile with Anita.[3]

Summary of Infant/Toddler Foundations in Social/Emotional Development

The key concepts in the Social/Emotional domain that provide an overview of the infants and toddlers social and emotional development are:

- Interactions with Adults: The developing ability to respond to and engage with adults

| 8 months | 18 months | 36 months |

| At around eight months of age, children purposefully engage in reciprocal interactions and try to influence the behavior of others. Children may be both interested in and cautious of unfamiliar adults. (7 mos.; Lame, Bornstein, and Teti 2002) (8 mos.; Meisels and others 2003, 16) | At around 18 months of age, children may participate in routines and games that involve complex back-and-forth interaction and may follow the gaze of the infant care teacher to an object or person. Children may also check with a familiar infant care teacher when uncertain about something or someone. (18 mos.; Meisels and others, 2003, 33) | At around 36 months of age, children interact with adults to solve problems or communicate about experiences or ideas. (California Department of Education 2005, 6; Marvin and Britner 1999, 60) |

- Relationships with Adults: The development of close relationships with certain adults who provide consistent nurturance Interactions with Peers: The developing ability to respond to and engage with other children

| 8 months | 18 months | 36 months |

| At around eight months of age, children seek a special relationship with one (or a few) familiar adult(s) by initiating interaction and seeking proximity, especially when distressed. (6-9 mos.; Marvin and Britner 1999, 52) | At around 18 months of age, children feel secure exploring the environment in the presence of important adults with whom they have developed a relationship over an extended period of time. When distressed, children seek to be physically close to these adults. (6-18 mos.; Marvin and Britner 1999, 52; Bowlby 1983) | At around 36 months of age, when exploring the environment, from time to time children reconnect, in a variety of ways, with the adult(s) with whom they have developed a special relationship: through eye contact; facial expressions; shared feelings; or conversations about feelings, shared activities, or plans. When distressed, children may still seek to be physically close to these adults. (By 36 mos.; Marvin and Britner 1999, 57) |

- Interactions with peers: The developing ability to respond to and engage with other children

| 8 months | 18 months | 36 months |

| At around eight months of age, children show interest in familiar and unfamiliar peers. Children may stare at another child, explore another child’s face and body, and respond to siblings and older peers. (8 mos.; Meisels and others 2003) | At around 18 months of age, children engage in simple back-and-forth interactions with peers for short periods of time. (Meisels and others 2003, 35) | At around 36 months of age, children engage in simple cooperative play with peers. (36 mos.; Meisels and others 2003 70) |

- Relationships with Peers: The development of relationships with certain peers through interactions over time

| 8 months | 18 months | 36 months |

| At around eight months of age, children show interest in familiar and unfamiliar children. (8 mos.; Meisels and others 2003, 17) | At around 18 months of age, children prefer to interact with one or two familiar children in the group and usually engage in the same kind of back-and-forth play when interacting with those children. (12-18 mos.; Mueller and Lucas 1975) | At around 36 months of age, children have developed friendships with a small number of children in the group and engage in more complex play with those friends than with other peers. |

- Identity of Self in Relation to Others: The developing concept that the child is an individual operating within social relationships

| 8 months | 18 months | 36 months |

| At around eight months of age, children show clear awareness of being a separate person and of being connected with other people. Children identify others as both distinct from and connected to themselves. (Fogel 2001, 347) | At around 18 months of age, children demonstrate awareness of their characteristics and express themselves as distinct persons with thoughts and feelings. Children also demonstrate expectations of others’ behaviors, responses, and characteristics on the basis of previous experiences with them. | At around 36 months of age, children identify their feelings, needs, and interests, and identify themselves and others as members of one or more groups by referring to categories. (24-36 mos.; Fogel 2001, 415; 18-30 mos.) |

- Recognition of Ability: The developing understanding that the child can take action to influence the environment

| 8 months | 18 months | 36 months |

| At around eight months of age, children understand that they are able to make things happen. | At around 18 months of age, children experiment with different ways of making things happen, persist in trying to do things even when faced with difficulty, and show a sense of satisfaction with what they can do. (McCarty, Clifton, and Collard 1999). | At around 36 months of age, children show an understanding of their own abilities when describing themselves. |

- Expression of Emotion: The developing ability to express a variety of feelings through facial expressions, movements, gestures, sounds, or words

| 8 months | 18 months | 36 months |

| At around eight months of age, children express a variety of primary emotions such as contentment, distress, joy, sadness, interest, surprise, disgust, anger, and fear. (Lamb, Bornstein, and Teti 2002, 341) | At around 18 months of age, children express emotions in a clear and intentional way, and begin to express some complex emotions, such as pride. | At around 36 months of age, children express complex, self-conscious emotions such as pride, embarrassment, shame, and guilt. Children demonstrate awareness of their feelings by using words to describe feelings to others or action them out in pretend play. (Lewis and others 1989; Lewis 2000b; Lagattuta and Thompson 2007)

|

- Empathy: The developing ability to share in the emotional experiences of others Emotion

| 8 months | 18 months | 36 months |

| At around eight months of age, children demonstrate awareness of others’ feelings by reacting to their emotional expressions. | At around 18 months of age, children change their behavior in response to the feelings of others even though their actions may not always make the other person feel better. Children show an increased understanding of the reason for another’s distress and may become distressed by the other’s distress. (14 mos.; Zahn-Waxler, Robinson, and Emde 1992; Thompson 1987; 24 mos.; Zahn-Waxler and Radke-Yarrow 1982, 1990) | At around 36 months of age, children understand that other people have feelings that are different from their own and can sometimes respond to another’s distress in a way that might make that person feel better. (24-36 mos.; Hoffman 1982; 18 mos.; Thompson 1987, 135) |

- Regulation: The developing ability to manage emotional responses with assistance from others and independently

| 8 months | 18 months | 36 months |

| At around eight months of age, children use simple behaviors to comfort themselves and begin to communicate the need for help to alleviate discomfort or distress. | At around 18 months of age, children demonstrate a variety of responses to comfort themselves and actively avoid or ignore situations that cause discomfort. Children can also communicate needs and wants through the use of a few words and gestures. (National Research Council and Institute of Medicine 2000, 112; 15-18 mos.; American Academy of Pediatrics 2004, 270; Coplan 1990, 1) | At around 36 months of age, children anticipate the need for comfort and try to prepare themselves for changes in routine. Children have many self-comforting behaviors to choose from, depending on the situation, and can communicate specific needs and wants. (Kopp 1989; CDE 2005) |

- Impulse Control: The developing capacity to wait for needs to be met, to inhibit potentially hurtful behavior, and to act according to social expectations, including safety rules

| 8 months | 18 months | 36 months |

| At around eight months of age, children act on impulses. (Birth-9 mos.; Bronson 2000b, 64) | At around 18 months of age, children respond positively to choices and limits set by an adult to help control their behavior. (18 mos.; Meisels and others 2003, 34; Kaler and Kopp 1990) | At around 36 months of age, children may sometimes exercise voluntary control over actions and emotional expressions. (Bronson 2000b, 67) |

- Social Understanding: The developing understanding of the responses, communication, emotional expressions, and actions of other people

| 8 months | 18 months | 36 months |

| At around eight months of age, children have learned what to expect from familiar people, understand what to do to get another’s attention, engage in back-and-forth interaction with others, and imitate the simple actions or facial expressions of others. | At around 18 months of age, children know how to get the infant care teacher to respond in a specific way through gestures, vocalizations, and shared attention; use another’s emotional expressions to guide their own response to unfamiliar events; and learn more complex behavior through imitation. Children also engage in more complex social interactions and have developed expectations for a greater number of familiar people. | At around 36 months of age, children can talk about their own wants and feelings and those of other people, describe familiar routines, participate in coordinate episodes of pretend play with peers, and interact with adults in more complex ways. |

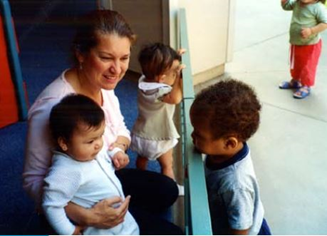

Foundations in Action

|

|

|

Looking at this sequence of images, what might have happened here? Which of the Social/Emotional Foundations do you see in these three images?

Language Development

Language development naturally occurs through ongoing interactions with adults. Babies have an inborn capacity to learn language that emerges by experiencing language input from adults. Experiences with language allow infants and toddlers to acquire mastery of sounds, grammar, and rules that guide communication and to share meaning with others.

Guiding principles of the language curriculum include:

- Be responsive to the active communicator and language learner

- Include language in your interactions with infants and toddlers

- Celebrate and support the individual

- Connect with children’s cultural and linguistic experiences at home

- Build on children’s interests

- Make communication and language interesting and fun

- Create literacy-rich environments

The environment should:

- Provide for exploration of books and other sources of print

- Moderate background noise

- Be arranged to support language development and communication

- Provide open-ended materials that foster communication

Caregivers should:

- Be responsive when children initiate communication

- Engage in nonverbal communication

- Use child-directed language

- Use self-talk and parallel talk (narrate their own and others actions)

- Help children expand language

- Support dual-language development

- Attend to individual development and needs

- Be playful with language[4]

Vignette

It is early in the morning, and 24-month-old Sabela is sitting quietly on the lap of her teacher, Sonja. Sonja and the other teachers talk about the day ahead. Sonja says to another child, “Tony, let’s go out early today. It’s supposed to rain this morning.” Sabela hops up, walks over to the cupboard, and takes out a bag of sand toys to play with outside. Taking out the sand toys and then collecting them to bring them back to the classroom is an activity that Sabela often helps with. Upon seeing Sabela move toward the back door, dragging the sack of sand toys, Sonja makes eye contact and smiles. Sonja also notes that Sabela understood Sonja’s comments to Tony.[5]

Summary of Infant/Toddler Foundation in Language Development

The key concepts in the Language domain that provide an overview of the infants and toddlers language and communication development are:

- Receptive Language: The developing ability to understand words and increasingly complex utterances

| 8 months | 18 months | 36 months |

| At around eight months of age, children show understanding of a small number of familiar words and react to the infant care teacher’s overall tone of voice. | At around 18 months of age, children show understanding of one-step requests that have to do with the current situation. | At around 36 months of age, children demonstrate an understanding of the means of others’ comments, questions, requests, or stories. (BY 36 mos.; American Academy of Pediatrics 2004, 307). |

- Expressive Language: The developing ability to produce the sounds of language and use vocabulary and increasingly complex utterances

| 8 months | 18 months | 36 months |

| At around eight months of age, children experiment with sounds, practice making sounds, and use sounds or gesture to communicate needs, wants, or interests. | At around 18 months of age, children say a few words and use conventional gestures to tell others about their needs, wants, and interests. (By 15 to 18 mos.; American Academy of Pediatrics 2004 270; Coplan 1993, 1; Hulit and Howard 2006, 142) | At around 36 months of age, children communicate in a way that is understandable to most adults who speak the same language they do. Children combine words into simple sentences and demonstrate the ability to follow some grammatical rules of the home language. (By 36 mos.; American Academy of Pediatrics 2004, 307; 30-36mos.; Lerner and Ciervo 2003; by 36 mos.; Hart and Risley 1999, 67)\ |

- Communication Skills and Knowledge: The developing ability to communicate nonverbally and verbally

| 8 months | 18 months | 36 months |

| At around eight months of age, children participate in back-and-forth communication and games. | At around 18 months of age, children use conventional gestures and words to communicate meaning in short back-and-forth interactions and use the basic rules of conversational turn-taking when communicating. (Bloom, Rocissano, and Hood 1976) | At around 36 months of age, children engage in back-and-forth conversations that contain a number of turns, with each turn building upon what was said in the previous turn. (Hart and Risely 1999, 122) |

- Interest in Print: The developing interest in engaging with print in books and in the environment

| 8 months | 18 months | 36 months |

| At around eight months of age, children explore books and show interest in adult-initiated literacy activities, such as looking at photos and exploring books together with an adult. (Scaled score of 10 for 7:16-8:15 mos.; Bayley 2006, 57; infants; National Research Council 1999, 28) | At around 18 months of age, children listen to the adult and participate while being read to by pointing, turning pages, or making one- or two-word comments. Children actively notice print in the environment. | At around 36 months of age, children show appreciation for books and initiate literacy activities: listening, asking questions, or making comments while being read to; looking at books on their own; or making scribble marks on paper and pretending to read what is written. (Schickedanz and Casbergue 2004, 11) |

What happens when a child cannot hear spoken language? They can learn to communicate through sign language. American Sign Language (ASL) is a complete, natural language that has the same linguistic properties as spoken languages, with grammar that differs from English. ASL is expressed by movements of the hands and face. It is the primary language of many North Americans who are deaf and hard of hearing, and is used by many hearing people as well.Parents are often the source of a child’s early acquisition of language, but for children who are deaf, additional people may be models for language acquisition. A deaf child born to parents who are deaf and who already use ASL will begin to acquire ASL as naturally as a hearing child picks up spoken language from hearing parents. However, for a deaf child with hearing parents who have no prior experience with ASL, language may be acquired differently. In fact, 9 out of 10 children who are born deaf are born to parents who hear. Some hearing parents choose to introduce sign language to their deaf children. Hearing parents who choose to have their child learn sign language often learn it along with their child. Children who are deaf and have hearing parents often learn sign language through deaf peers and become fluent.Parents should expose a deaf or hard-of-hearing child to language as soon as possible. The earlier a child is exposed to and begins to acquire language, the better that child’s language, cognitive, and social development will become. Research suggests that the first few years of life are the most crucial to a child’s development of language skills, and even the early months of life can be important for establishing successful communication with caregivers. Thanks to screening programs in place at almost all hospitals in the United States and its territories, newborn babies are tested for hearing before they leave the hospital. If a baby has hearing loss, this screening gives parents an opportunity to learn about communication options. Parents can then start their child’s language learning process during this important early stage of development.[6]

Cognitive Development

The term cognitive development refers to the process of growth and change in intellectual or mental abilities such as thinking, reasoning, and understanding. It includes the acquisition and consolidation of knowledge. Over the past three decades, infancy research has caused developmental psychologists to change the way they characterize the earliest stages of cognitive development. Once regarded as an organism driven mainly by simple sensorimotor schemes, the infant is now seen as having sophisticated cognitive skills and concepts that guide knowledge acquisition.

Guiding principles of the language curriculum include:

- Relate to the child as an active learner

- Provide opportunities for exploration

- Respect the child’s initiative and choices

- Allow ample time for children to make sense of experiences

- Appreciate the child’s creativity

- Describe the child’s actions and effects of actions

- Support self-initiated repetition and practice

- Give appropriate encouragement for problem solving and mastery

- Support the child’s activity participation in personal care routines

The environment should:

- Provide play spaces with rich opportunities for learning

- Provide storage/display of toys in places that are easily visible and accessible

- Include both novelty and predictability

- Be arranged to encourage exploration

- Provide nesting and stacking toys to support an understanding of spatial relationships

- Provide toys that support cause-and-effect experimentation

- Include toys and props for and be arranged to support pretend play

- Provide toys that support the collection and storage of treasures

Caregivers should:

- Notice what interests the child

- Use language to engage each child’s intellect

- Use personal care routines to support cognitive development[7]

Vignette

Jenna has been crawling for several weeks now and is getting quite fast at moving around. This morning, her teacher, Archie, is watching closely as Jenna crawls up the wide ramp to a platform where there are several large, plastic boxes of different sizes. Jenna crawls up to a box and sticks her head inside it, as if she were going to crawl into the box.

Archie knows she will not be able to fit her entire body inside the box, but Jenna is already halfway inside it. Archie scoots up the ramp to Jenna, who may be feeling a little stuck at this point, and gently places his hand on Jenna’s back, saying, “You put your head in this big box, and the rest of you is out here with me. I’m here, Jenna.”

Jenna pulls her head out, looks at Archie, and then vocalizes, “Ahhh, ya, ya” and gestures toward the box. Archie smiles and says, “Yes, I saw you with your head in there. I came right up here in case you needed me, but you got yourself out, didn’t you?” Jenna looks back at Archie, and then at the box, a few times. Then she bangs on the box with her hands and crawls to a larger box. She glances back at Archie, who smiles, and she crawls in, fitting into the larger box quite easily. “You are in the big box, Jenna. You sure are, and I’m out here.” Jenna smiles and bangs on the box while vocalizing her triumph. [8]

Summary of Infant/Toddler Foundation in Cognitive Development

The key concepts in the Cognitive domain that provide an overview of the infants and toddlers cognitive development are:

- Cause-and-Effect: The developing understanding that one event brings about another

| 8 months | 18 months | 36 months |

| At around eight months of age, children perform simple actions to make things happen, notice the relationships between events, and notice the effects of others on the immediate environment. | At around 18 months of age, children combine simple actions to cause things to happen or change the way they interact with objects and people in order to see how it changes the outcome. | At around 36 months of age, children demonstrate an understanding of cause and effect by making predictions about what would happen and reflect upon what caused something to happen. (California Department of Education [CDE] 2005) |

- Spatial Relationships: The developing understanding of how things move and fit in space

| 8 months | 18 months | 36 months |

| At around eight months of age, children move their bodies, explore the size and shape of objects, and observe people and objects as they move through space. | At around 18 months of age, children use trial and error to discover how things move and fit in space (12-18 mos.; Parks 2004, 81) | At around 36 months of age, children can predict how things will fit and move in space without having to try out every possible solution, and show understanding of words used to describe size and locations in space. |

- Problem Solving: The developing ability to engage in a purposeful effort to reach a goal or figure out how something works

| 8 months | 18 months | 36 months |

| At around eight months of age, children use simple actions to try to solve problems involving objects, their bodies, or other people. | At around 18 months of age, children use a number of ways to solve problems: physically trying out possible solutions before finding one that works; using objects as tools; watching someone else solve the problem and then applying the same solution; or gesturing or vocalizing to someone else for help. | At around 36 months of age, children solve some problems without having to physically try out every possible solution and may ask for help when needed. (By 36 mos.; American Academy of Pediatrics 2004, 308) |

- Imitation The developing ability to mirror, repeat, and practice the actions of others, either immediately or later

| 8 months | 18 months | 36 months |

| At around eight months of age, children imitate simple actions and expressions of others during interactions. | At around 18 months of age, children imitate others’ actions that have more than one step and imitate simple actions that they have observed others doing at an earlier time. (Parks 2004; 28) | At around 36 months of age, children reenact multiple steps of others’ actions that they have observed at an earlier time. (30-36 mos.; Parks 2004, 29) |

- Memory: The developing ability to store and later retrieve information about past experiences

| 8 months | 18 months | 36 months |

| At around eight months of age, children recognize familiar people, objects, and routines in the environment and show awareness that familiar people still exist even when they are no longer physically present. | At around 18 months of age, children remember typical actions of people, the location of objects, and steps of routines. | At around 36 months of age, children anticipate the series of steps in familiar activities, events, or routines; remember characteristics of the environment or people in it; and may briefly describe recent past events or act them out. (24-36 mos.; Seigel 1999, 33) |

- Number Sense: The developing understanding of number and quantity

| 8 months | 18 months | 36 months |

| At around eight months of age, children usually focus on one object or person at a time, yet they may at times hold two objects, one in each hand. | At around 18 months of age, children demonstrate understanding that there are different amounts of things. | At around 36 months of age, children show some understanding that numbers represent how many and demonstrate understanding of words that identify how much. (By 36 mos.; American Academy of Pediatrics 2004, 308) |

- Classification: The developing ability to group, sort, categorize, connect, and have expectations of objects and people according to their attributes

| 8 months | 18 months | 36 months |

| At around eight months of age, children distinguish between familiar and unfamiliar people, places, and objects, and explore the difference between them. (Barrera and Mauer 1981) | At around 18 months of age, children show awareness when objects are in some way connected to each other, match two objects that are the same, and separate a pile of objects into two groups based on one attribute. (Mandler and McDonough 1998) | At around 36 months of age, children group objects into multiple piles based on one attribute at a time, put things that are similar but not identical into one group, and may label each grouping, even though sometimes these labels are overgeneralized. (36 mos.; Mandler and McDonough 1993) |

- Symbolic Play: The developing ability to use actions, objects, or ideas to represent other actions, objects, or ideas

| 8 months | 18 months | 36 months |

| At around eight months of age, children become familiar with objects and actions through active exploration. Children also build knowledge of people, action, objects, and ideas through observation. (Fenson and others 1976; Rogoff and others 2003) | At around 18 months of age, children use one object to represent another object and engage in one or two simple actions of pretend play. | At around 36 months of age, children engage in make-believe play involving several sequenced steps, assigned roles, and an overall plan and sometimes pretend by imagining an object without needing the concrete object present. (30-36 mos.; Parks 2004, 29) |

- Attention Maintenance: The developing ability to attend to people and things while interacting with others and exploring the environment and play materials

| 8 months | 18 months | 36 months |

| At around eight months of age, children pay attention to different things and people in the environment in specific, distinct ways. (Bronson 200, 64) | At around 18 months of age, children rely on order and predictability in the environment to help organize their thoughts and focus attention. (Bronson 2000, 191) | At around 36 months of age, children sometimes demonstrate the ability to pay attention to more than one thing at a time. |

- Understanding of Personal Care Routines: The developing ability to understand and participate in personal care routines

| 8 months | 18 months | 36 months |

| At around eight months of age, children are responsive during the steps of personal care routines. (CDE 2005) | At around 18 months of age, children show awareness of familiar personal care routines and participate in the steps of these routines. (CDE 2005) | At around 36 months of age, children initiate and follow through with some personal care routines. (CDE 2005) |

Discoveries of Infancy

Learning Schemes

Learning schemes are the building blocks for all other discovery during infancy. By using schemes such as banging, reaching, and mouthing, children gain valuable information about things. Scheme development helps children discover how objects are best used and how to use objects in new and interesting ways.

Cause and Effect

As infants develop, they begin to understand that events and outcomes are caused. They learn that:

They can cause things to happen either with their own bodies or through their own actions.

Other people and objects can cause things to happen.

Specific parts of objects, for example, wheels, light switches, knobs, and buttons on cameras, can cause specific effects.

Use of Tools

Tools are anything children can use to accomplish what they want. Among the tools infants use are a cry, a hand, a caregiver, and an object. Infants learn to extend their power through the use of tools. They learn that a tool is a means to an end.

Object Permanence

For young infants, ‘out of sight’ often means ‘out of mind.’ Infants are not born knowing about the permanence of objects. They make this important discovery gradually through repeated experiences with the same objects, such as a bottle, and the same persons, such as their mother or father. Infants learn that things exist even when one cannot see them.

Understanding Space

Much of early learning has to do with issues of distance, movement, and perspective. Infants learn about spatial relationships through bumping into things, squeezing into tight spaces, and seeing things from different angles. In a sense, infants and toddlers at play are young scientists, busily investigating the physical universe. For example, they find out about:

- Relative size as they try to fit an object into a container

- Gravity as they watch play cars speedily roll down a slide

- Balance as they try to stack things of different shapes and sizes

Imitation

One of the most powerful learning devices infants and toddlers use is imitation. It fosters the development of communication and a broad range of other skills.

Even very young infants learn from trying to match other people’s actions. . . .

As infants develop, their imitations become increasingly complex and purposeful. . . . At every stage of infancy, children repeat and practice what they see. By doing the same thing over and over again they make it their own.”

—Discoveries of Infancy: Cognitive Development and Learning (PITC child care Video Magazine)[9]

Pause to Reflect

How do these discoveries of infancy relate to the Cognitive Foundations? How might you use both to plan engaging curriculum for infants and toddlers?

Perceptual and Motor Development

Perception refers to the process of taking in, organizing, and interpreting sensory information. Perception is multimodal, with multiple sensory inputs contributing to motor responses. Motor development refers to changes in a child’s ability to control his body movements, from the infant’s first spontaneous waving and kicking movements to the adaptive control of reaching, locomotion, and complex sport skills. Gross motor actions include the movement of large limbs or the whole body, such as walking. Fine motor behaviors include the use of fingers to grasp and manipulate objects. Motor behaviors such as touching and grasping are forms of exploratory activity.

Guiding principles of perceptual and motor development curriculum include:

- Recognize the child’s developing abilities

- Encourage self-directed movement

- Respect individual differences

- Provide a safe place for each age group

- Be available to children as they move and explore

- The environment should:

- Include materials that support perceptual and motor development, focusing on the children’s interests and how to expand on those interests

- Provide many opportunities for movement and large motor play, both indoors and outdoors

- Provide safe, but challenging spaces where children can move, both indoors and outdoors

- Establish physical boundaries for moving and exploring with the arrangement of furniture and space

- Protect young children’s need for sheltered spaces

- Be arranged safely

- Allow children to move easily

- Include everyday objects and materials

- Provide a variety of sensory and motor experiences

Caregivers should:

- Provide the infant with freedom to move

- See things from the infant’s perspective

- Help build the infant’s feelings of comfort, security, and awareness of his body

- Use common routines, activities, and behaviors to allow for practice of perceptual and motor skills

- Acknowledge each child’s accomplishments. [10]

Vignette

Seven-month-old Abasi is seated comfortably in teacher Stephen’s lap, ready for lunch. Abasi tugs at his bib and watches intently as Stephen fills a bowl with orange baby food. Abasi opens his mouth when Stephen holds up a full spoon for him to see. Stephen gently moves the spoon to Abasi’s lips, and Abasi closes his mouth on the spoon. Almost immediately, Abasi spits out the spoon and food and grimaces. Stephen is surprised. Abasi refuses another bite and ends up having a bottle instead. Stephen mentions this episode to Abasi’s grandmother at pickup time. She laughs and says, “His favorite food is peaches, but that was carrots. I told his Mama that it would be a nasty surprise for him!” Abasi watches as the two adults laugh together. Stephen comments, “Abasi, you looked at the orange color and expected your favorite—peaches. What a surprise to taste carrots!”[11]

Summary of Infant/Toddler Foundations in Perceptual and Motor Development

It is important to recognize that, though developmental charts may show motor development unfolding in the form of a smooth upward progression toward mastery, the development of individual children often does not follow a smooth upward trajectory. In fact, “detours” and steps backward are common as development unfolds.[12]

The key concepts in the Perceptual and Motor Development domain that provide an overview of the infants and toddlers perceptual and motor development are:

- Perceptual Development: The developing ability to become aware of the social and physical environment through the senses

| 8 months | 18 months | 36 months |

| At around eight months of age, children use the senses to explore objects and people in the environment. (6-9 mos.; Ruff and Kohler 1978) | At around 18 months of age, children use the information received from the senses to change the way they interact with the environment. | At around 36 months of age, children can quickly and easily combine the information received from the senses to inform the way they interact with the environment. |

- Gross Motor: The developing ability to move the large muscles

| 8 months | 18 months | 36 months |

| At around eight months of age, children demonstrate the ability to maintain their posture in a sitting position and to shift between sitting and other positions. | At around 18 months of age, children move from one place to another by walking and running with basic control and coordination. | At around 36 months of age, children move with ease, coordinating movements and performing a variety of movements. |

- Fine Motor: The developing ability to move the small muscles

| 8 months | 18 months | 36 months |

| At around eight months of age, children easily reach for and grasp things and use eyes and hands to explore objects actively. (6 mos.; Alexander, Boehme, and Cupps 1993, 112) | At around 18 months of age, children are able to hold small objects in one hand and sometimes use both hands together to manipulate objects. (18 mos.; Meisels and others 2003, 40) | At around 36 months of age, children coordinate the fine movements of the fingers, wrists, and hands to skillfully manipulate a wide range of objects and materials in intricate ways. Children often use one hand to stabilize an object while manipulating it. |

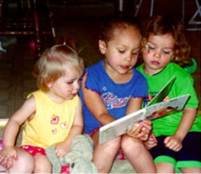

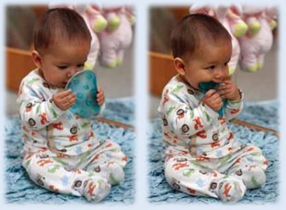

Foundations in Action

These two images capture all three of the Perception and Motor Foundations. Can you see how all of these are at play here?

- The California Infant/Toddler Curriculum Framework by the California Department of Education is used with permission ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- American Sign Language by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services is in the public domain ↵

- The California Infant/Toddler Curriculum Framework by the California Department of Education is used with permission ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵