17.1 Documentation

Knowing What to Document

One of the biggest challenges facing early childhood educators is efficient use of time and the need to document what is significant. What do you document? How do you know what is significant? You cannot possibly document everything and it tends to become meaningless if this occurs. Educators need to select the important moments. You can’t write in detail about every child, and you can’t do it every day! However, in time you can gather pictures and stories about all the children to give a better idea about who they are and their dispositions.

Educators are keen observers. They notice not only what children are doing, but also what and how they are playing and what they are saying during play. This puts them in a strong position to develop a program based on their observations.

When trying to determine when and how to document, ask yourself:

- Why am I recording this—what is meaningful/significant?

- What is the learning occurring?

- How can we extend on this?

- How does it link to the outcomes we are measuring?[1]

Purposes of Documentation

Documentation serves different purposes at different times. The criteria for what counts as quality documentation depends on the context in which you are using it. What seems to remain constant is that quality documentation focuses on some aspect of learning—not just ‘what we did.’ It prompts questions and promotes conversations among children and adults that deepen and extend learning.

There are three good reasons to document observations in school age care:

- to inform program planning

- to deepen our understanding of the children

- to make learning visible and share it with others.[2]

To Inform Curriculum Planning

Documentation makes children’s and educators’ thinking visible. It allows children and educators to revisit it, reflect, uncover meaning and plan future directions. A program direction often comes from a simple moment spent in conversation or play with a child: a moment which makes us pause and reflect.

Ordinary moments are the pages in the child’s diary for the day. If we could resist our temptation to record only the grand moments, we might find the authentic child living in the in-between. If we could resist our temptation to put the children on a stage, we might find the real work being done in the wings. If we understood the great value in the ordinary moments, we might be less inclined to have a marvellous finale for a long term project. We appeal to educators everywhere to find the marvel in the mundane, to find the power of the ordinary moment![3]

(Forman, Hall & Berglund, 2001, p.52-3)

Before documenting, you should ask: Why am I documenting this? How is this significant? If there is not a worthwhile reason, there may not be good reasons for recording.

There are different ways in which observations can be recorded, such as:

- note pads carried around by individuals

- sticky notes which may be gathered over a period of time and used for reflection clipboards

- group journals/communication books

- video recorder

- camera

- voice recorder

- poster/spreadsheet

The documentation taken for program planning can be recorded in one place by all educators or it can be recorded individually (such as in notebooks) and brought together with the group during discussion.

Notes just need to act as a visual reminder to stimulate thought and plans for planning.[4]

Think of yourself in the classroom with young children. What might you want to capture with documentation? Why? What methods do you think would best capture these?

Reflective Thinking and Discussion to Deepen Our Understanding of the Children

Jotting down observations for later discussion helps educators, particularly new and inexperienced ones, reflect and analyse, which can lead to deeper understanding for the educators in the setting.

These observations may be recorded in a variety of ways, such as quick summaries on sticky notes, captioned photographs, or entries in child portfolios. What is important, however, is the fact that the learning has been made visible and the educators may share knowledge about this and question and extend it further. True collaborative planning can occur when educators share recorded observations. Once again there are a variety of ways to undertake this, but group discussion during meeting time is an ideal way to promote this deeper understanding and shared wisdom.

Encourage all educators in your setting to question why children’s play is significant. The thinking is more complex and needs to go beyond just thinking ‘they are playing in the home corner again’. Ask yourself why the children are choosing particular role-playing scenarios. What inspired it? Who is involved? Does it reflect an event or experience in a child’s life that they are choosing to act out in play? Is someone trying to work through some emotions? Are they undertaking family life lessons at school? What meaning are they getting from it? What misinterpretations are there? How can I assist their learning in this area? How can we build on this learning?

Curtis and Carter (2008) suggest examining children’s play from three angles:

- The child’s story (Why are they playing this? What fascinates them about this? What is their previous experience? How can I encourage them to show more?)

- The learning story

- The educator’s story (What excites you? What are you curious about? How can you find out more?)

During training, many educators have been encouraged to look at learning and developmental aspects; however, to engage in deeper thinking, it is important to consider all three perspectives.[5]

Making Learning Visible and Sharing it With Others

Educators may make some documentation visible to showcase the learning which has occurred and to find ways to connect with others. When you document a child’s story you give the child a voice, and have a valuable tool for opening a meaningful discussion with that child’s family. It is also a means to engage with other educators, such as teachers in the child’s school. Children also love to go back and reflect on documented moments.

There are numerous ways to document for others to see. Some options include:

Wall Displays/Documentation Panels

Documenting and displaying the children’s project work allows them to express, revisit, and construct and reconstruct their feelings, ideas and understandings. Pictures of children engaged in experiences; their words as they discuss what they are doing, feeling and thinking; and the children’s interpretation of experience through the visual media are displayed as a graphic presentation of the dynamics of learning. Documented wall displays or documentation panels is a Reggio Emilia concept which aims to place emphasis on the process, not just the end product.

Making images of learning visible and being together in a group is a way to foster group identity and learning. This type of documentation promotes conversation or deepens understanding about one or more aspects of a learning experience. It can serve as a memory experience, allowing children and adults to reflect on, evaluate, and build on their previous ideas. Sharing documentation with learners can take many forms: a photocopied sheet of paper, words, scrapbook pages, or a carefully arranged panel.

Learning Stories

A learning story is an alternative to other forms of observations. Margaret Carr developed this narrative form of assessment to meet documentation requirements in New Zealand to demonstrate knowledge and understanding of each child. In learning stories, educators capture significant moments throughout the day with photos and then tell the story of the child’s learning (Carr, 2001).

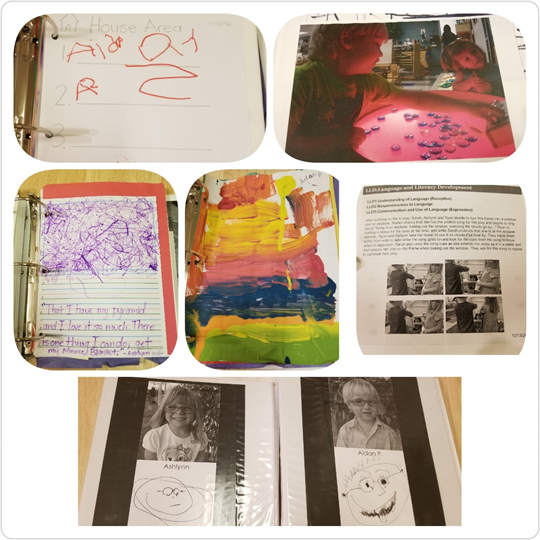

Portfolios

A portfolio could document a child’s development over time and highlight each child’s learning story. The portfolio belongs to the child and contains their work and their stories. Portfolios are as individual as the children and they don’t follow a prescribed pattern or format, they can just evolve. School age care is a social setting and children’s portfolios should contain photos and stories of their friends, but be mindful of children and families who do not wish their photos to be included in others’ folders and find strategies to deal with this. Portfolios and scrapbooks are long-term projects which can be undertaken jointly by the children and educators.

Vignette

The educators at our school age care decided they wanted to improve the basic child files and develop new and improved individual child portfolios. Some of the educators attended professional development sessions and spoke to other services to get feedback on how others set up portfolios.

We looked at scrap books, display books, worksheets and folders. We liked the idea of a display book into which we could easily slip pages and photos. We also liked the idea of a scrap book where children could paste, draw, collage and write and which they could make quite personal.

We considered developing a ‘contents page’, but thought not all children would be interested in completing all the experiences in the contents. We also had a huge selection of worksheets including about me, family trees, self-portraits, birthdays, special things, coat of arms, pets, friends and when I grow up.

Educators decided that, rather than a standard format, they wanted each child’s portfolio to be unique to the individual. We wanted choice and variety: written work, photos, typed stories, collage, artwork, scrapbooking.

As space is limited at our service, we wanted something that was easy to store so that the children could easily find their portfolio without flicking through or moving other children’s portfolios.

The solution:

- one display book per child

- type each child’s name on the labelling machine and stick it on the spine of the display book

- put the display books in alphabetical order in plastic tubs

- provide each child with an notebook and place this in the front of the display book to be used as a scrap book/journal

- copy all the different sheets we have sourced and place each in a plastic pocket in a folder so that children can ‘choose’ what they want to include in their portfolio

- set up a folder for each child on the children’s laptop so that children’s photos and learning stories can be stored and easily accessed.

The result:

- The children were so excited to have their own personal, individual portfolios.

- The children are able to easily access their portfolios.

- The children can browse through the worksheet folder and choose what they would like to do.

- Some children have stuck records of other experiences they have done at school age care in their

- journals/scrap books.

- Some children have shown their portfolios to their families.

- Educators have gone through all our ‘old’ photos and placed them in the new child portfolios. Children and families have enjoyed revisiting past experience at school age care by looking at the photos from previous years.

- Some children have sat down with educators to share their portfolios and this has assisted educators to get to know the children.

We decided that in the future we would:

- encourage children to self-initiate what items they want to file in their portfolio

- print a list of all children that attend school age care. Each term, check each child’s portfolio and document what they have included.

- encourage those that have not filed anything to complete a sheet or learning story. Educators could place a photo in the child’s portfolio and then ask the child to tell the educator about that experience and how they felt.

- ask the children what they want to include in their portfolios. What other resources can educators provide?

- look at child portfolios at a staff meeting and evaluate how effective our new system has been and where we can improve.

How can we keep the children motivated once the novelty wears off?[6]

What are pros and cons to the different ways of documenting children presented here? Why might an educator want to use each? What might be some drawbacks?

What are other types of documentation to consider that weren’t provided here?

Children’s Voice in Documentation

Educators can gain valuable insight by creating a culture of listening to and working collaboratively with children. How do you know what the children in your care want from their time in care?

There is a strong synergy between children’s being and belonging and their active involvement in democratic processes, and having an impact on what the environment, programs and partnerships look, sound and feel like. The information you gather from children is integral to the development of a program that meets their needs and interests.

A range of ways can be used to gather and document children’s voices in school age care settings including:

- ‘All about me’ sheets, where children and families document important information about themselves, such as likes, dislikes, hobbies and such

- setting time to have informal and formal discussions with children

- children interviewing other children

- suggestion boxes and surveys

- recording children’s comments and thoughts about experiences as part of the evaluation process

- children’s portfolios

- reating opportunities for joint planning, including setting up of the care environment

- photographing children and asking them to write about the experience

- children writing their own learning stories

- joint problem-solving opportunities.

Careful consideration needs to be given to children who may be non-verbal or have difficulty expressing themselves to ensure their voices are heard in your care setting.[7]

Ethical Considerations

When documenting children’s learning, educators must be respectful of the rights of children and families. Permission must be sought from children and families before information is collected and documented. Children and families must have the right to privacy, be informed about how the information will be used and have a choice about participating.

MacNaughton, Smith and Lawrence suggest that to protect and enhance children’s rights through consultation with them, adults should ensure that children have:

- safe spaces in which to share their ideas without challenge or critique

- privacy: ask children for permission to document/ record what they say

- ownership of their ideas: ask children to display and/ or share their ideas and understandings with others

- appropriate equipment with which adults can care for children’s work in ways that shows that their voice is important and respected

Some further questions to consider when thinking about documentation include:

- What does observing, documenting and evaluating look like in your setting?

- How do you involve children in the process?

- How do you involve families in the process?

- How do you know what is valued or expected for children within the family and cultural context?

- Do you assess children at an individual level? Do you think this is important in your setting?

- How do you define ‘regular’ in the context of children who attend ‘regularly’?

- What methods or tools would you use?

- Does the documentation focus on learning, not just something you did?

- Does the documentation promote conversation or deepen understanding about some aspect of learning?

- What documentation do you collect which is appropriate to share/display?

- Does the documentation focus on outcomes for children and not just what the educators are doing?

- Does the documentation focus on the process as well as the product(s)?

- Does the documentation clearly communicate the aspects of learning you consider most important?

- Does your display documentation have a title?

- Is the documentation presented in a way that draws the viewer in?

Documentation does not need to be repeated. A narrative story with photos can be shared at a staff meeting, with input from all educators about links, questions, and where ideas may be built upon. The story can then be displayed in the room (as a work in progress or perhaps with an end product if there is one). The child can show people who are important to them the documentation and it will open up discussion with families, children and educators. Once it has been displayed for a period of time it can be filed away in the child’s portfolio, where it can be revisited at any time. It is also available if an assessor wants to look at it during a visit as well. So this one piece of documentation serves many purposes.[8]

- Australian Government Department of Education (n.d.) Educator My Time, Our Place. Retrieved from files.acecqa.gov.au/files/National-Quality-Framework-Resources-Kit/educators_my_time_our_place.pdf ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Australian Government Department of Education (n.d.) Educator My Time, Our Place. Retrieved from files.acecqa.gov.au/files/National-Quality-Framework-Resources-Kit/educators_my_time_our_place.pdf ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵