12 Curriculum Models

Curriculum Models provide a framework to organize planning experiences for children. In previous chapters, the planning cycle has been introduced and in accordance with best practices, the models identified in this chapter represent a variety of ways to use the planning cycle within these models.

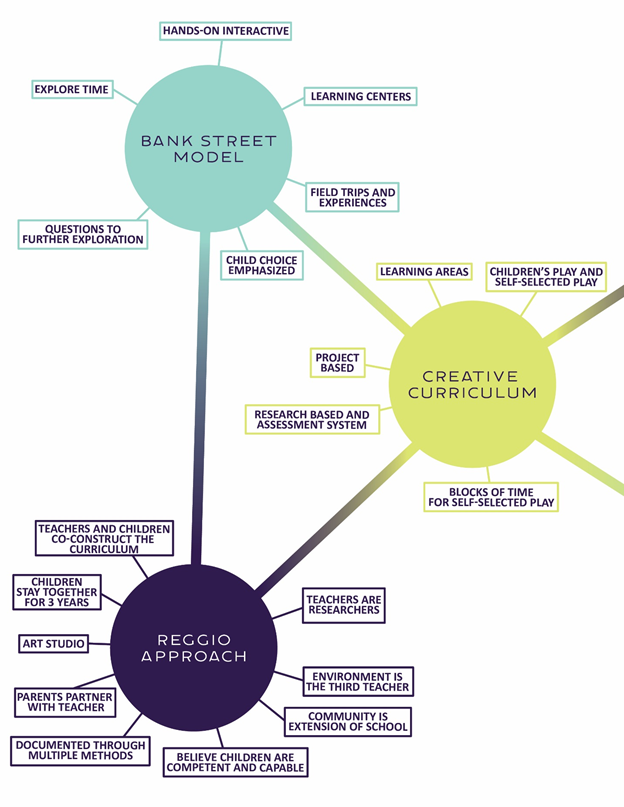

Bank Street Model

Lucy Sprague Mitchell founded Bank Street, an Integrated Approach also referred to as the Developmental-Interactionist Approach.

In this model, the environment is arranged into learning centers and planning is organized by the use of materials within the learning areas (centers).

- Art

- Science

- Sensory/Cooking

- Dramatic Play

- Language/Literacy

- Math/Manipulative/Blocks

- Technology

- Outdoors: Water and Sand Play

The Bank Street Model of curriculum represents the ideology of Freud, Erikson, Dewey, Vygotsky, and Piaget. This model draws upon the relationship between psychology and education. By understanding developmental domains and creating interest centers with materials that promote specific areas of development, children’s individual preferences and paces of learning are the focus.

“A teacher’s knowledge and understanding of child development is crucial to this approach. Educational goals are set in terms of developmental processes and include the development of competence, a sense of autonomy and individuality, social relatedness and connectedness, creativity and integration of different ways of experiencing the world”.[1]

Creative Curriculum Model (Diane Trister Dodge)

In the Creative Curriculum model, the focus is primarily on children’s play and self-selected activities. The Environment is arranged into learning areas and large blocks of time are given for self-selected play. This model focuses on project-based investigations as a means for children to apply skills and addresses four areas of development: social/emotional, physical, cognitive, and language.

The curriculum is designed to foster development of the whole child through teacher-led, small and large group activities centered around 11 interest areas:

- blocks

- dramatic play

- toys and games

- art

- library

- discovery

- sand and water

- music and movement

- cooking

- computers

- outdoors.

The commercial curriculum provides teachers with details on child development, classroom organization, teaching strategies, and engaging families in the learning process. Child assessments are an important part of the curriculum, but must be purchased separately. Online record-keeping tools assist teachers with the maintenance and organization of child portfolios, individualized planning, and report production.[2]

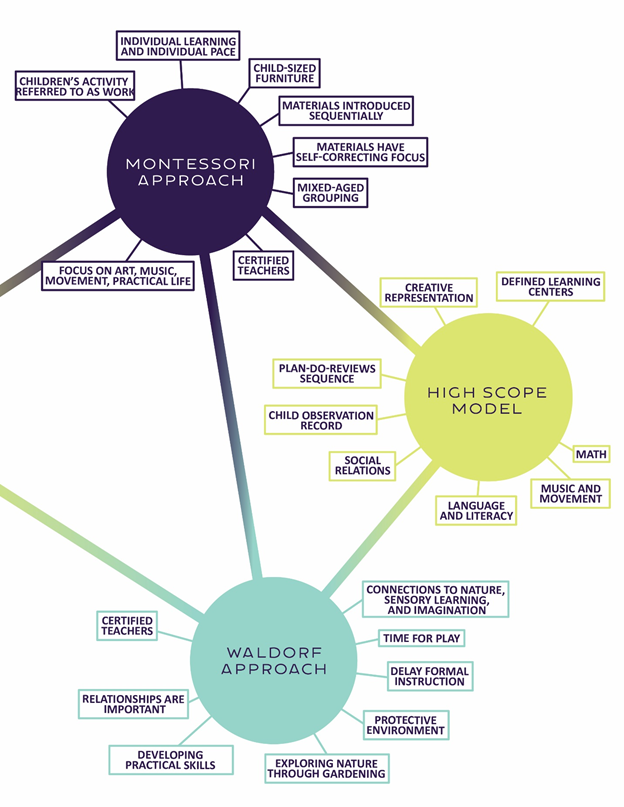

High Scope Model (David Weikert)

The High Scope Model focuses on developing learning centers similar to the Bank Street Model and emphasizes key experiences for tracking development. The key experiences are assessed using a Child Observation Record for tracking development and include areas of:

- Creative Representation

- Initiative

- Social Relations

- Language and Literacy

- Math (Classification, Seriation, Number, Space, Time)

- Music and Movement

The High Scope Model also includes a “Plan-Do-Review” Sequence in which children begin their day planning for activities they will participate in, followed by participation in the activities and engaging in a review session at the end of the day. Teachers can use this sequence format to help children learn how to organize choices of activities and to reflect upon what they liked or would do different at the end of the day. The High Scope Model reflects the theories of Piaget, Vygotsky and Reggio Emilia by way of emphasis on construction of knowledge through hands-on experiences with reflection techniques.

Montessori Approach (Dr. Maria Montessori)

The Montessori Approach refers to children’s activity as work (not play); children are given long periods of time to work and a strong emphasis on individual learning and individual pace is valued. Central to Montessori’s method of education is the dynamic triad of child, teacher and environment. One of the teacher’s roles is to guide the child through what Montessori termed the ‘prepared environment, i.e., a classroom and a way of learning that are designed to support the child’s intellectual, physical, emotional and social development through active exploration, choice and independent learning.

The educational materials have a self-correcting focus and areas of the curriculum consist of art, music, movement, practical life (example; pouring, dressing, cleaning). In the Montessori method, the goal of education is to allow the child’s optimal development (intellectual, physical, emotional and social) to unfold.

A typical Montessori program will have mixed-age grouping. Children are given the freedom to choose what they work on, where they work, with whom they work, and for how long they work on any particular activity, all within the limits of the class rules. No competition is set up between children, and there is no system of extrinsic rewards or punishments.[3]

Waldorf Approach (Rudolf Steiner)

The Waldorf Approach, founded by Rudolf Steiner, features connections to nature, sensory learning, and imagination. The understanding of the child’s soul, of his or her development and individual needs, stands at the center of Steiner’s educational world view.

The Waldorf approach is child centered.[4] It emerges from a deep understanding of child development and seeks to support the particular developmental tasks (physical, emotional and intellectual) children face at any given stage. Children aged 3–5, for example, are developing a keen interest in the world, supported to a large extent by freedom of movement and must be supported to follow and deepen their curiosity through the encouragement of their sometimes endless asking of questions (Van Alphen & Van Alphen 1997). This approach to supporting children’s naturally blossoming curiosity, rather than answering the teachers’ questions. At this stage, children’s play becomes increasingly complex, with children spontaneously engaging in role plays, as they construct and act upon imaginative situations based on their own experiences and stories they have heard. Thus, in Waldorf schools, ample time is given for free imaginative play as a cornerstone of children’s early learning.[5]

The environment should protect children from negative influences and curriculum should include exploring nature through gardening, but also developing in practical skills, such as cooking, sewing, cleaning, etc. Relationships are important so groupings last for several years, by way of looping.

Reggio Emilia Approach (Loris Malaguzzi)

The Reggio Emilia approach to early childhood education is based on over forty years of experience in the Reggio Emilia Municipal Infant/toddler and Preschool Centers in Italy. Central to this approach is the view that children are competent and capable.

It places emphasis on children’s symbolic languages in the context of a project-oriented curriculum. Learning is viewed as a journey and education as building relationships with people (both children and adults) and creating connections between ideas and the environment. Through this approach, adults help children understand the meaning of their experience more completely through documentation of children’s work, observations, and continuous teacher-child dialogue. The Reggio approach guides children’s ideas with provocations—not predetermined curricula. There is collaboration on many levels: parent participation, teacher discussions, and community.

Within the Reggio Emilia schools, great attention is given to the look and feel of the classroom. Environment is considered the “third teacher.” Teachers carefully organize space for small and large group projects and small intimate spaces for one, two, or three children. Documentation of children’s work, plants, and collections that children have made from former outings are displayed both at the children’s and adult’s eye level. Common space available to all children in the school includes dramatic play areas and worktables.

There is a center for gathering called the atelier (art studio) where children and children from different classrooms can come together. The intent of the atelier in these schools is to provide children with the opportunity to explore and connect with a variety of media and materials. The studios are designed to give children time, information, inspiration, and materials so that they can effectively express their understanding through the “inborn inheritance of our universal language, the language that speaks with the sounds of the lips and of the heart, the children’s learning with their actions, their signs, and their eyes: those “hundred languages” that we know to be universal. There is an atelierista (artist) to support this process and instruct children in arts.[6]

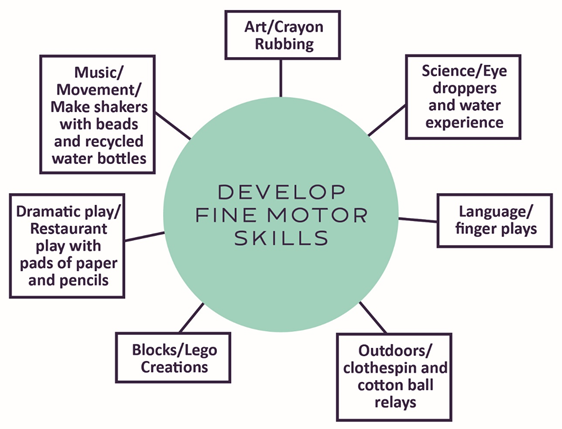

Webbing

The Reggio Emilia Approach is an emergent curriculum. One method that many Early Childhood Educators use when planning emergent curriculum is curriculum webbing based on observed skills or interests. This method uses brainstorming to create ideas and connections from children’s interests to enhance developmental skills. Webbing can look like a “Spider’s Web” or it can be organized in list format.

Webbing can be completed by:

- An individual teacher

- A team of teachers

- Teachers and Children

- Teachers, Children and Families

Webbing provides endless planning opportunities as extensions continue from observing the activities and following the skills and interests exhibited. As example demonstrates a web can begin from a skill to develop, but it can also be used in a Theme/Unit Approach such as transportation; friendships; animals, nature, etc.

Project Approach

The project approach is an in-depth exploration of a topic that may be child-or teacher-initiated and involve an individual, a group of children, or the whole class. A project may be short-term or long-term depending on the level of children’s interests. What differentiates the project approach from an inquiry one is that within the project approach there is an emphasis on the creation of a specific outcome that might take the form of a spoken report, a multimedia presentation, a poster, a demonstration or a display. The project approach provides opportunities for children to take agency of their own learning and represent this learning through the construction of personally meaningful artefacts. If utilized effectively, possible characteristics may include: active, agentic, collaborative, explicit, learner-focused, responsive, scaffolded, playful, language-rich and dialogic.[7]

In the project approach, adults and children investigate topics of discovery using six steps: Observation, Planning, Research, Exploration, Documentation, Evaluation.

- Observation: A teacher observes children engaging with each other or with materials and highlights ideas from the observations to further explore.

- Planning: Teachers talk with children about the observation and brainstorm ideas about the topic and what to explore

- Research: Teachers find resources related to the topic

- Explore: Children engage with experiences set around the topic to create hypotheses and make predictions and formulate questions

- Documentation: Teachers write notes, create charts and children draw observations and fill in charts as they explore topics/questions

- Evaluate: Teachers and children can reflect on the hypotheses originally developed and compare their experiences to predictions. Evaluation is key in determining skills enhanced and what worked or what didn’t work and why.

The benefits of a project approach are that young learners are directly involved in making decisions about the topic focus and research questions, the processes of investigation and in the selection of the culminating activities. When young learners take an active role in decision making, agency and engagement is promoted.

As young learners take ownership of their learning they, ‘feel increasingly competent and sense their own potential for learning so they develop feelings of confidence and self-esteem’ (Chard, 2001).[8]

Culturally Appropriate Approach[9]

The Cultural Appropriate Approach has evolved over the years and the practice of valuing children’s culture is imperative for children to feel a sense of belonging in ECE programs. Sensitivity to the variety of cultures within a community can create a welcoming atmosphere and teach children about differences and similarities among their peers. Consider meeting with families prior to starting the program to share about cultural beliefs, languages and or traditions. Classroom areas can reflect the cultures in many ways:

- Library Area: Select books that represent cultures in the classroom

- Dramatic Area: Ask families to donate empty boxes of foods they commonly use, bring costumes or clothes representative of culture

- Language: In writing center include a variety of language dictionaries;

- Science: Encourage families to come and share a traditional meal

Attribution

This chapter is copied from unit 4.1 in Introduction to Curriculum for Early Childhood Education by Jennifer Paris, Kristin Beeve, & Clint Springer shared under a CC BY license.

- Gordon, A. M. & Browne, K. W. (2001) Beginnings and Beyond, 8th edition. Wadsworth, Cengage Learning. (pg. 364) ↵

- The Creative Curriculum for Preschool, Fourth Edition by the U.S. Department of Education. Public domain. ↵

- Montessori education: a review of the evidence base by Chloë Marshall is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- On the Unique Place of Art in Waldorf Education by Gilad Goldshmidt is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Imagination, Waldorf, and critical literacies: Possibilities for transformative education in mainstream schools by Monica Shank is licensed under CC BY 2.0 ↵

- Reggio Emilia Theory and Application by One Community is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- Age Appropriate Pedagogies Project by Hanstweb is licensed under CC BY ↵

- Age Appropriate Pedagogies Project by Hanstweb is licensed under CC BY ↵

- Child Growth and Development by Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, and Dawn Rymond is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵