33 Monitoring, Screening and Evaluating

Chapter Objectives

In this chapter, you will be learning about:

- The Purpose of Monitoring, Screening and Evaluating Young Children.

- The Process of Monitoring.

- The Process of Screening and Evaluating.

- The Practice of Monitoring.

- The Practice of Screening and Evaluating.

- Public Policies on Including Children with Special Needs.

Introduction

It is essential that Early Childhood Educators be able to recognize typical from atypical development. With typical development, there are certain behavioural expectations and developmental milestones that children should master within certain age ranges. Any behaviour and development that falls outside of the standard norms would be considered a-typical. As early care providers, how do we know whether a child’s development is happening at a normal, excelled or delayed pace? How can we be certain that we are providing an optimal learning space for each child? As intentional teachers our goal is to accommodate all the varied skill levels and diverse needs of the children in our classrooms. Additionally, we must provide a safe, nurturing and culturally respectful environment that promotes inclusion so that all children can thrive. In this chapter we will examine the purpose, process and practice of monitoring, screening and evaluating young children. If we are to effectively support the children and families in our care, we must be able to identify a child’s capabilities and strengths early on, as well as recognize any developmental delays or developmental areas that may need additional support. Additionally, we must be aware of the resources and services that are available to support children and families.

The Purpose of Monitoring, Screening and Evaluating Young Children

Because many parents are not familiar with developmental milestones, they might not recognize that their child has a developmental delay or disability.

Developmental disability (DD) is a common type of disability, defined as an impairment in cognitive function that presents prior to adulthood and persists throughout a person’s life[1]. The number of individuals impacted by DD in Canada is large. Estimates of the percentage of children in Canada with DD have ranged from 6.5 to 8.3% and many people with DD experience lifelong limitations that impact their quality of life[2].[3]

What’s more concerning is that many children are not being identified as having a delay or disability until they are in elementary school. Subsequently, they will not receive the appropriate support and services they need early on to be successful at school. It has been well-documented, in both educational and medical professional literature, that developmental outcomes for young children with delays and disabilities can be greatly improved with early identification and intervention.[4] While some parents might be in denial and struggling with the uncertainty of having a child with special needs, some parents might not be aware that there are support services available for young children and they may not know how to advocate for their child. Thus, as early child educators we have an obligation to help families navigate through the process of monitoring, as well as provide information and resources if a screening or evaluation is necessary.

The Process of Monitoring

Who can monitor a child’s development? Parents, grandparents, early caregivers, providers and teachers can monitor the children in their care. One of the tasks of an intentional teacher is to gather baseline data within the first 60 days of a child starting their program. With each observation, teachers are listening to how a child speaks and if they can communicate effectively; they are watching to see how the child plays and interacts with their peers; and they are recording how the child processes information and problem solves. By monitoring a child closely, not only can we observe how a child grows and develops, we can track changes over time. More importantly, we can identify children who fall outside the parameters of what is considered normal or “typical” development.

When teachers monitor children, they are observing and documenting whether children are mastering “typical” developmental milestones in the physical, cognitive, language, emotional and social domains of development. In particular, teachers are tracking a child’s speech and language development, problem-solving skills, fine and gross motor skills, social skills and behaviours, so that they can be more responsive to each child’s individual needs. Even more so, teachers are trying to figure out what a child can do, and if there are any “red flags” or developmental areas that need further support. As early caregivers and teachers, we are not qualified to formally screen and evaluate children. We can however monitor children’s actions, ask questions that can guide our observations, track developmental milestones, and record our observations. With this vital information we can make more informed decisions on what is in the child’s best interest.

What is this Child Trying to Tell Me?

With 12-24 busy children in a classroom, there are bound to be occasional outbursts and challenging behaviours to contend with. In fact, a portion of a teacher’s day is typically spent guiding challenging behaviours. With all the numerous duties and responsibilities that a teacher performs daily, dealing with challenging behaviours can be taxing. When a child repeats a challenging behaviour, we might be bothered, frustrated, or even confused by their actions. We might find ourselves asking questions like:

- “Why does she keep pinching her classmate?”

- “Why does he put his snack in his hair?”

- “Why does he cry when it’s clean up time or when he has to put his shoes on?”

- “Why does she fidget so much during group time?”

Without taking the time to observe the potential causes and outcomes associated with the challenging behaviour, we may only be putting on band-aids to fix a problem, rather than trying to solve the problem. Without understanding the why, we cannot properly guide the child or support the whole-child’s development. As intentional teachers we are taught to observe, document, and analyze a child’s actions so we can better understand what the child is trying to “tell” us through their behaviour. Behaviour is a form of communication. Any challenging behaviour that occurs over and over, is happening for a reason. If you can find the “pattern” in the behaviour, you can figure out how to redirect or even stop the challenging behaviour.

Finding Patterns

To be most effective, it is vital that we record what we see and hear as accurately and objectively as possible. No matter which observation method, tool or technique is used (e.g. Event Sampling, Frequency Counts, Checklists or Technology), once we have gathered a considerable amount of data we will need to interpret and reflect on the observation evidence so that we can plan for the next step. Finding the patterns can be instrumental in planning curriculum, setting up the environment with appropriate materials, and creating social situations that are suitable for the child’s temperament.

Patterns and Play

If Wyatt is consistently observed going to the sandbox to play with dinosaurs during outside play:

- What does this tell you?

- What is the pattern?

- Is Wyatt interacting with other children?

- How is Wyatt using the dinosaurs?

- How can you use this information to support Wyatt during inside play?

Ideas for Wyatt

To create programming encourage the child to go into the art center, knowing that he likes dinosaurs, lay down some butcher paint on a table, put a variety of dinosaurs out on the table, and add some trays with various colors of paint.

To arrange the environment add books and pictures about dinosaurs, and materials that could be used in conjunction with dinosaurs.

To support social development: I noticed Wyatt played by himself on several observations. I may need to do some follow up observations to see if Wyatt is initiating conversations, taking turns, joining in play with others or playing alone.

As you can see these are just a few suggestions. What ideas did you come up with? As we monitor children in our class, we are gathering information so that we can create a space where each child’s individual personality, learning strengths, needs, and interests are all taken into account. Whether the child has a disability, delay or impairment or is developing at a typical pace, finding their unique pattern will help us provide suitable accommodations

What is a Red Flag?

If, while monitoring a child’s development, a “red flag” is identified, it is the teacher’s responsibility to inform the family, in a timely manner, about their child’s developmental progress. First, the teacher and family would arrange a meeting to discuss what has been observed and documented. At the meeting, the teacher and family would share their perspectives about the child’s behaviour, practices, mannerisms, routines and skill sets. There would be time to ask questions and clarify concerns, and a plan of action would be developed. It is likely that various adjustments to the environment would be suggested to meet the individual child’s needs, and ideas on how to tailor social interactions with peers would be discussed. With a plan in place, the teacher would continue to monitor the child. If after a few weeks there was no significant change or improvement, the teacher may then recommend that the child be formally screened and evaluated by a professional (e.g. a pediatrician, behavioural psychologist or a speech pathologist).

The Process of Screening and Evaluating

Who can screen and evaluate children? Doctors, pediatricians, speech pathologists, behaviourists, Screenings and evaluations are more formal than monitoring. Developmental screening takes a closer look at how a child is developing using brief tests. Your child will get a brief test, or you will complete a questionnaire about your child. The tools used for developmental and behavioural screening are formal questionnaires or checklists based on research that ask questions about a child’s development, including language, movement, thinking, behaviour, and emotions.

Developmental screenings are cost effective and can be used to assess a large number of children in a relatively short period of time. There are screenings to assess a child’s hearing and vision, and to detect notable developmental delays. Screenings can also address some common questions and concerns that teachers, and parents alike, may have regarding a child’s academic progress. For example, when a teacher wonders why a child is behaving in such a way, they will want to observe a child’s social interactions and document how often certain behaviours occur. Similarly, when a parent voices a concern that their child is not talking in complete sentences the way their older child did at that same age. The teacher will want to listen and record the child’s conversations and track their language development.

Developmental Delays – is the condition of a child being less developed mentally or physically than is normal for their age.

Developmental Disabilities[footnote]Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]. (n.d.). Facts About Developmental Disabilities. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/developmentaldisabilities/facts.html[/footnote] — developmental disabilities are a group of conditions due to an impairment in physical, learning, language, or behaviour areas. These conditions begin during the developmental period, may impact day-to-day functioning, and usually last throughout a person’s lifetime. Some noted disabilities include:

- ADHD

- Autism Spectrum Disorder

- Cerebral Palsy

- Hearing Loss

- Vision Impairment

- Learning Disability

- Intellectual Disability

Screening Young Children

To quickly capture a snapshot of a child’s overall development, early caregivers and teachers can select from several observation tools to observe and document a child’s play, learning, growth and development. Systematic and routine observations, made by knowledgeable and responsive teachers, ensure that children are receiving the quality care and support they deserve. Several observation tools and techniques can be used by teachers to screen a child’s development. Because each technique and tool provides limited observation data, it is suggested that teachers use a combination of tools and techniques to gather a full panoramic perspective of a child’s development. Here are some guidelines:

- Monitoring cannot capture the complete developmental range and capabilities of children, but can provide a general overview

- Monitoring can only indicate the possible presence of a developmental delay and cannot definitively identify the nature or extent of a disability

- Not all children with or at risk for delays can be identified

- Some children who are red-flagged may not have any actual delays or disabilities; they may be considered “exceptional” or “gifted”

- Children develop at different paces and may achieve milestones at various rates

Developmental Milestone Checklists and Charts

There are many factors that can influence a child’s development: genetics, gender, social interactions, personal experiences, temperaments and the environment. It is critical that educators understand what is “typical” before they can consider what is “atypical.” Developmental Milestones provide a clear guideline as to what children should be able to do at set age ranges. However, it is important to note that each child in your classroom develops at their own individualized pace, and they will reach certain milestones at various times within the age range.

Developmental Milestone Charts are essential when setting up your classroom environments. Once you know what skills children should be able to do at specific ages, you can then plan developmentally appropriate learning goals, and you can set up your classroom environment with age appropriate materials. Developmental Milestone Charts are also extremely useful to teachers and parents when guiding behaviours. In order to set realistic expectations for children, it is suggested that teachers and parents review all ages and stages of development to understand how milestones evolve. Not only do skills build upon each other, they lay a foundation for the next milestone that’s to come. Developmental Milestone Charts are usually organized into 4 Domains: Physical, Cognitive, Language, and Social-Emotional.

| Table 1: Gross Motor Milestones 2 Months to 2 Years – What Most Children Do[5] | |

| 2 months | Can hold head up and begins to push up when lying on tummy |

| Makes smoother movements with arms and legs | |

| 4 months | Holds head steady, unsupported |

| Pushes down on legs when feet are on a hard surface | |

| May be able to roll over from tummy to back | |

| Brings hands to mouth | |

| When lying on stomach, pushes up to elbows | |

| 6 months | Rolls over in both directions (front to back, back to front) |

| Begins to sit without support | |

| When standing, supports weight on legs and might bounce | |

| Rocks back and forth, sometimes crawling backward before moving forward | |

| 9 months | Stands, holding on |

| Can get into sitting position | |

| Sits without support | |

| Pulls to stand | |

| Crawls | |

| 1 year | Gets to a sitting position without help |

| Pulls up to stand, walks holding on to furniture (“cruising”) | |

| May take a few steps without holding on | |

| May stand alone | |

| 18 months | Walks alone |

| May walk up steps and run | |

| Pulls toys while walking | |

| Can help undress self | |

| 2 years | Stands on tiptoe |

| Kicks a ball | |

| Begins to run | |

| Climbs onto and down from furniture without help | |

| Walks up and down stairs holding on | |

| Throws ball overhand | |

| Table 2: Fine Motor Milestones 2 Months to 2 Years – What Most Children Do | |

| 2 months | Grasps reflexively |

| Does not reach for objects | |

| Holds hands in fist | |

| 4 months | Brings hands to mouth |

| Uses hands and eyes together, such as seeing a toy and reaching for it | |

| Follows moving things with eyes from side to side | |

| Can hold a toy with whole hand (palmar grasp) and shake it and swing at dangling toys | |

| 6 months | Reaches with both arms |

| Brings things to mouth | |

| Begins to pass things from one hand to the other | |

| 9 months | Puts things in mouth |

| Moves things smoothly from one hand to the other | |

| Picks up things between thumb and index finger (pincer grip) | |

| 1 year | Reaches with one hand |

| Bangs two things together | |

| Puts things in a container, takes things out of a container | |

| Lets things go without help | |

| Pokes with index (pointer) finger | |

| 18 months | Scribbles on own |

| Can help undress herself | |

| Drinks from a cup | |

| Eats with a spoon with some accuracy | |

| Stacks 2-4 objects | |

| 2 years | Builds towers of 4 or more blocks |

| Might use one hand more than the other | |

| Makes copies of straight lines and circles | |

| Enjoys pouring and filling | |

| Unbuttons large buttons | |

| Unzips large zippers | |

| Drinks and feeds self with more accuracy | |

| Table 3: Cognitive Milestones 2 Months to 2 Years – What Most Children Do | |

| 2 months | Pays attention to faces |

| Begins to follow things with eyes and recognize people at a distance | |

| Begins to act bored (cries, fussy) if activity doesn’t change | |

| 4 months | Lets you know if she is happy or sad |

| Responds to affection | |

| Reaches for toy with one hand | |

| Uses hands and eyes together, such as seeing a toy and reaching for it | |

| Follows moving things with eyes from side to side | |

| Watches faces closely | |

| Recognizes familiar people and things at a distance | |

| 6 months | Looks around at things nearby |

| Brings things to mouth | |

| Shows curiosity about things and tries to get things that are out of reach | |

| Begins to pass things from one hand to the other | |

| 9 months | Watches the path of something as it falls |

| Looks for things he sees you hide | |

| Plays peek-a-boo | |

| Puts things in mouth | |

| Moves things smoothly from one hand to the other | |

| Picks up things like cereal o’s between thumb and index finger | |

| 1 year | Explores things in different ways, like shaking, banging, throwing |

| Finds hidden things easily | |

| Looks at the right picture or thing when it’s named | |

| Copies gestures | |

| Starts to use things correctly; for example, drinks from a cup, brushes hair | |

| Bangs two things together | |

| Puts things in a container, takes things out of a container | |

| Lets things go without help | |

| Pokes with index (pointer) finger | |

| Follows simple directions like “pick up the toy” | |

| 18 months | Knows what ordinary things are for; for example, telephone, brush, spoon |

| Points to get the attention of others | |

| Shows interest in a doll or stuffed animal by pretending to feed | |

| Points to one body part | |

| Scribbles on own | |

| Can follow 1-step verbal commands without any gestures; for example, sits when you say “sit down” | |

| 2 years | Finds things even when hidden under two or three covers |

| Begins to sort shapes and colors | |

| Completes sentences and rhymes in familiar books | |

| Plays simple make-believe games | |

| Builds towers of 4 or more blocks | |

| Might use one hand more than the other | |

| Follows two-step instructions such as “Pick up your shoes and put them in the closet.” | |

| Names items in a picture book such as a cat, bird, or dog | |

| Table 4: Language Milestones 2 Months to 2 Years – What Most Children Do | |

| 2 months | Coos, makes gurgling sounds |

| Turns head toward sounds | |

| 4 months | Begins to babble |

| Babbles with expression and copies sounds he hears | |

| Cries in different ways to show hunger, pain, or being tired | |

| 6 months | Responds to sounds by making sounds |

| Strings vowels together when babbling (“ah,” “eh,” “oh”) and likes taking turns with parent while making sounds | |

| Responds to own name | |

| Makes sounds to show joy and displeasure | |

| Begins to say consonant sounds (jabbering with “m,” “b”) | |

| 9 months | Understands “no” |

| Makes a lot of different sounds like “mamamama” and “bababababa” | |

| Copies sounds and gestures of others | |

| Uses fingers to point at things | |

| 1 year | Responds to simple spoken requests |

| Uses simple gestures, like shaking head “no” or waving “bye-bye” | |

| Makes sounds with changes in tone (sounds more like speech) | |

| Says “mama” and “dada” and exclamations like “uh-oh!” | |

| Tries to say words you say | |

| 18 months | Says several single words |

| Says and shakes head now | |

| Points to show others what is wanted | |

| 2 years | Points to things or pictures when they are named |

| Knows names of familiar people and body parts | |

| Says sentences with 2 to 4 words | |

| Follows simple instructions | |

| Repeats words overheard in conversation | |

| Points to things in a book | |

| Table 5: Social and Emotional Milestones 2 Months to 2 Years – What Most Children Do | |

| 2 months | Begins to smile at people |

| Can briefly calm self (may bring hands to mouth and suck on hand) | |

| Tries to look at parent | |

| 4 months | Smiles spontaneously, especially at people |

| Likes to play with people and might cry when playing stops | |

| Copies some movements and facial expressions, like smiling or frowning | |

| 6 months | Knows familiar faces and begins to know if someone is a stranger |

| Likes to play with others, especially parents | |

| Responds to other people’s emotions and often seems happy | |

| Likes to look at self in a mirror | |

| 9 months | May be afraid of strangers |

| May be clingy with familiar adults | |

| Has favorite toys | |

| 1 year | Is shy or nervous with strangers |

| Cries when mom or dad leaves | |

| Has favourite things and people | |

| Shows fear in some situations | |

| Hands you a book when she wants to hear a story | |

| Repeats sounds or actions to get attention | |

| Puts out arm or leg to help with dressing | |

| Plays games such as “peek-a-boo” and “pat-a-cake” | |

| 18 months | Likes to hand things to others as play |

| May have temper tantrums | |

| May be afraid of strangers | |

| Shows affection to familiar people | |

| Plays simple pretend, such as feeding a doll | |

| May cling to caregivers in new situations | |

| Points to show others something interesting | |

| Explores alone but with parent close by | |

| 2 years | Copies others, especially adults and older children |

| Gets excited when with other children | |

| Shows more and more independence | |

| Shows defiant behaviour (doing what he has been told not to) | |

| Plays mainly beside other children, but is beginning to include other children, such as in chase games | |

| Table 6: Gross Motor Milestones 3 Years to 5 Years – What Most Children Do | |

| 3 years | Climbs well |

| Runs easily | |

| Pedals a tricycle (3-wheel bike) | |

| Walks up and down stairs, one foot on each step | |

| 4 years | Hops and stands on one foot up to 2 seconds |

| Catches a bounced ball most of the time | |

| 5 years | Stands on one foot for 10 seconds or longer |

| Hops; may be able to skip | |

| Can do a somersault | |

| Can use the toilet on own | |

| Swings and climbs | |

| Table 7: Fine Motor Milestones 3 Years to 5 Years – What Most Children Do | |

| 3 years | Copies a circle with pencil or crayon |

| Turns book pages one at a time | |

| Builds towers of more than 6 blocks | |

| Screws and unscrews jar lids or turns door handle | |

| 4 years | Pours, cuts with supervision, and mashes own food |

| Draws a person with 2 to 4 body parts | |

| Uses scissors | |

| Starts to copy some capital letters | |

| 5 years | Can draw a person with at least 6 body parts |

| Can print some letters or numbers | |

| Copies a triangle and other geometric shapes | |

| Uses a fork and spoon and sometimes a table knife | |

| Table 8: Cognitive Milestones 3 Years to 5 Years – What Most Children Do | |

| 3 years | Can work toys with buttons, levers, and moving parts |

| Plays make-believe with dolls, animals, and people | |

| Does puzzles with 3 or 4 pieces | |

| Understands what “two” means | |

| 4 years | Names some colors and some numbers |

| Understands the idea of counting | |

| Starts to understand time | |

| Remembers parts of a story | |

| Understands the idea of “same” and “different” | |

| Plays board or card games | |

| Tells you what he thinks is going to happen next in a book | |

| 5 years | Counts 10 or more things |

| Knows about things used every day, like money and food | |

| Table 9: Language Milestones 3 Years to 5 Years – What Most Children Do | |

| 3 years | Follows instructions with 2 or 3 steps |

| Can name most familiar things | |

| Understands words like “in,” “on,” and “under” | |

| Says first name, age, and sex | |

| Names a friend | |

| Says words like “I,” “me,” “we,” and “you” and some plurals (cars, dogs, cats) | |

| Talks well enough for strangers to understand most of the time | |

| Carries on a conversation using 2 to 3 sentences | |

| 4 years | Knows some basic rules of grammar, such as correctly using “he” and “she” |

| Sings a song or says a poem from memory such as the “Itsy Bitsy Spider” or the “Wheels on the Bus” | |

| Tells stories | |

| Can say first and last name | |

| 5 years | Speaks very clearly |

| Tells a simple story using full sentences | |

| Uses future tense; for example, “Grandma will be here.” | |

| Says name and address | |

| Table 10: Social and Emotional Milestones 3 Years to 5 Years – What Most Children Do | |

| 3 years | Copies adults and friends |

| Shows affection for friends without prompting | |

| Takes turns in games | |

| Shows concern for a crying friend | |

| Dresses and undresses self | |

| Understands the idea of “mine” and “his” or “hers” | |

| Shows a wide range of emotions | |

| Separates easily from mom and dad | |

| May get upset with major changes in routine | |

| 4 years | Enjoys doing new things |

| Is more and more creative with make-believe play | |

| Would rather play with other children than by self | |

| Cooperates with other children | |

| Plays “mom” or “dad” | |

| Often can’t tell what’s real and what’s make-believe | |

| Talks about what she likes and what she is interested in | |

| 5 years | Wants to please friends |

| Wants to be like friends | |

| More likely to agree with rules | |

| Likes to sing, dance, and act | |

| Is aware of gender | |

| Can tell what’s real and what’s make-believe | |

| Shows more independence | |

| Is sometimes demanding and sometimes very cooperative | |

Time Sampling or Frequency Counts

When a teacher wants to know how often or how infrequent a behaviour is occurring, they will use a Frequency Count to track a child’s behaviour during a specific timeframe. This technique can help teachers track a child’s social interactions, play preferences, temperamental traits, aggressive behaviours, and activity interests.

Checklists

When a teacher wants to look at a child’s overall development, checklists can be a very useful tool to determine the presence or absence of a particular skill, milestone or behaviour. Teachers will observe children during play times, circle times and centers, and will check-off the skills and behaviours as they are observed. Checklists help to determine which developmental skills have been mastered, which skills are emerging, and which skills have yet to be learned.

Technology

Teachers can use video recorders, cameras and tape recorders to record children while they are actively playing. This is an ideal method for capturing authentic quotes and work samples. Information gathered by way of technology can also be used with other screening tools and techniques as supporting evidence. (Note: it is important to be aware of center policies and procedures regarding proper consent before photographing or taping a child).

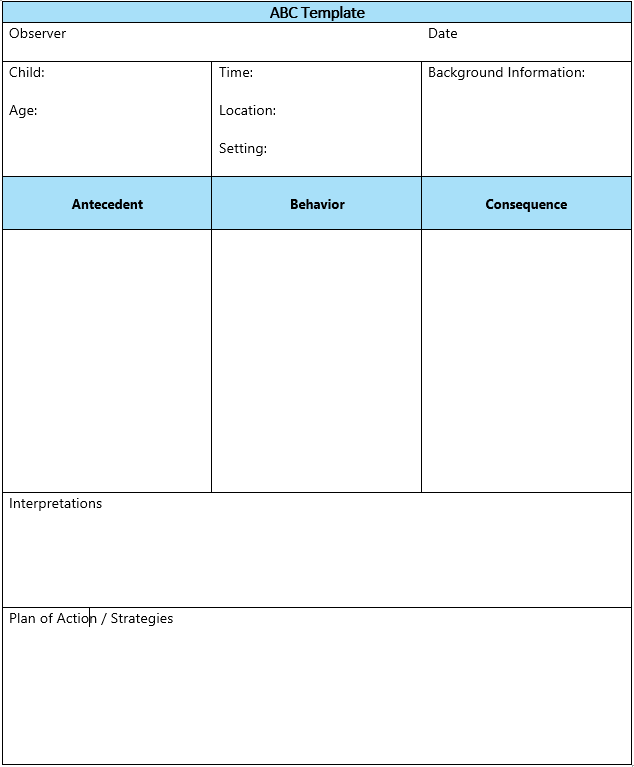

Event Sampling and the ABC Technique

When an incident occurs, we may wonder what triggered that behaviour. The Event Sampling or ABC technique helps us to identify the social interactions and environmental situations that may cause children to react in certain ways. If we are to reinforce someone’s positive behaviour, or change someone’s negative behaviour, we must first try to understand what might be causing that particular behaviour. With an ABC Analysis, the observer is looking for and tracking a specific behaviour. More than the behaviour itself, the observer wants to understand what is causing the behaviour – this is antecedent. The antecedent happens before the behaviour. It is believed that if the observer can find the “triggers” that might be leading up to or causing the challenging behaviour, then potential strategies can be planned to alter, redirect or end the challenging behaviour. In addition to uncovering the antecedent, what happens after the behaviour is just as important, this is the “consequence.” How a child is treated after the incident or challenging behaviour can create a positive or negative reinforcement pattern. In short, the ABC technique tells a brief story of what is happening before, during, and after a noted behaviour.

The ABC observation method requires some training and practice. The observer must practice being neutral and free of bias, judgement and assumption in order to collect and record objective evidence and to portray an accurate picture. Although it may be uncomfortable to admit, certain behaviours can frustrate a teacher. If the teacher observes a child while feeling frustrated or annoyed, this can possibly taint the observation data. It is important to record just the facts. And to review the whole situation before making any premature assumptions.

Collecting your data

If you have a concern about a child’s behaviour or if you have noticed a time when a child’s behaviour has been rather disruptive, you will schedule a planned observation. For this type of observation, you can either video record the child in classroom environment, or you can take observation notes using a Running Record or Anecdotal Record technique. To find a consistent pattern, it is best to tape or write down your observations for several days to find a true and consistent pattern. To document your observations, include the child’s name, date, time, setting, and context. Observe and write down everything you see and hear before, during and after the noted behaviour.

Organizing your data

Divide a piece of paper into 3 sections: A – for Antecedent; B – for Behaviour; and C – for Consequence. Using your observation notes you will organize the information you collected into the proper sections. As you record the observation evidence, remember to report just the facts as objectively as possible. Afterwards, you will interpret the information and look for patterns. For example, did you find any “triggers” before the behaviour occurred? What kind of “reinforcement” did the child receive after the behaviour? What are some possible strategies you can try to minimize or redirect the challenging behaviour? Do you need to make environmental changes? Are their social interactions that need to be further monitored? With challenging behaviours, there is not a quick fix or an easy answer. You must follow through and continue to observe the child to see if your strategies are working.

The ABC Method

(A) Antecedent: Right before an incident or challenging behaviour occurs, something is going on to lead up to or prompt the actual incident or behaviour.

For example, one day during lunch Susie spills her milk (this behaviour has happened several times before). Rather than focusing solely on the incident itself (Susie spilling the milk), look to see what was going on before the incident. More specifically, look to see if Susie was in a hurry to finish her snack so she could go outside and play? Was Susie being silly? Which hand was Susie using – is this her dominant hand? Is the milk pitcher too big for Susie to manipulate?

(B) Behaviour: This refers to the measurable or observable actions.

In this case, it is Susie spilling the milk.

(C) Consequence: The consequence is what happens directly after the behaviour.

For example, right after Susie spilt the milk, did you yell at her or display an unhappy or disgusted look? Did Susie cry? Did Susie attempt to clean up the milk? Did another child try to help Susie?

Antecedent Behavior Consequence: ABC Charts & Model by Teachings in Education[6]

The Practice of Screening and Evaluating

Beyond monitoring, once a child has been “red-flagged” they will need to be assessed by a professional who will use a formal diagnostic tool to evaluate the child’s development. Families can request that a formal screening be conducted at the local elementary school if their child is 3 to 5 years old. Depending upon the nature of the red flag, there are a battery of tools that can be used to evaluate a child’s development. Here are some guidelines:

- Screenings are designed to be brief (30 minutes or less)

- A more comprehensive assessment and formal evaluation must be conducted by a professional in order to confirm or disconfirm any red flags that were raised during the initial monitoring or screening process

- Families must be treated with dignity, sensitivity and compassion while their child is going through the screening process

- Use a screening tool from a reputable publishing company

Screening Instruments and Evaluation Tests

The instruments listed below are merely a sample of some of the developmental and academic screening tests that are widely used.

- Ages and Stages Questionnaires (ASQ®-3), Brookes Publishing Company

- Battelle Developmental Inventory Screening Test (BDI-3®), Riverside Publishing

- Developmental Indicators for Assessment of Learning (DIAL-4), Pearson Assessments

- Dynamic Indicators of Basic Early Literacy Skills (DIBELS®), University of Oregon Center on Teaching and Learning

- Early Screening Inventory-Revised (ESI-R), Pearson Assessments (includes separate scoring for preschool and kindergarten)[7]

Reliability and Validity Defined

Reliability means that the scores on the tool will be stable regardless of when the tool is administered, where it is administered, and who is administering it. Reliability answers the question: Is the tool producing consistent information across different circumstances? Reliability provides assurance that comparable information will be obtained from the tool across different situations.

Validity means that the scores on the tool accurately capture what the tool is meant to capture in terms of content. Validity answers the question: Is the tool assessing what it is supposed to assess?

Children with Special Needs

Throughout the past 40 years there have been some significant changes in public policy and social attitudes towards integrating children with special needs and learning disabilities into typical classroom settings. Stigmas from the past have dissipated and more inclusive practices are in place.

Early childhood inclusion embodies the values, policies, and practices that support the right of every infant and young child and his or her family, regardless of ability, to participate in a broad range of activities and contexts as full members of families, communities, and society. The desired results of inclusive experiences for children with and without disabilities and their families include a sense of belonging and membership, positive social relationships and friendships, and development and learning to reach their full potential. The defining features of inclusion that can be used to identify high quality early childhood programs and services are access, participation, and supports.[8]

When early caregivers and preschool teachers practice monitoring as part of their regular routines, they demonstrate accountability and responsive caregiving. Nearly 65% of children are identified as having a special need, disability, delay or impairment, and will require some special services or intervention. As early educators our role is twofold:

- Provide an environment where children feel safe, secure and cared for

- Help children develop coping skills to decrease stress and promote learning and development

Individualized Education Plans

Some children may need more individualized support and might benefit from specialized services or individual accommodations. The child care team plans appropriately accommodations, modifications and makes recommendations that will help the child meet their developmental goals.

While everyone on the team has a role, the teacher’s role is to integrate approaches that can best support the child while in class. For example, if the plan notes that the child needs support with language development, the teacher would consider finding someone in class who could provide peer to peer scaffolding. The teacher would want to find someone who has strong language skills, and who is cooperative and kind to others. She would then partner the two children up throughout the day so that the typical child could model ideal language skills. The teacher would also provide regular updates to parents, continue observing and monitoring the child’s development, and would provide access to alternative resources and materials as much as possible.

Creating Inclusive Learning Environments

To ensure that all children feel safe, secure and nurtured, teachers must strive to create a climate of cooperation, mutual respect and tolerance. To support healthy development, teachers must offer multiple opportunities for children to absorb learning experiences, as well as process information, at their own pace. While one child may be comfortable with simple verbal instructions to complete a particular task, another child may benefit from a more direct approach such as watching another child or adult complete the requested task first. Teachers who are devoted to observing their children are motivated to provide experiences that children will enjoy and be challenged by. The classroom is not a stagnant environment – it is ever-changing. In order to maintain a high-quality classroom setting, it is essential to utilize your daily observations of children and the environment to monitor the experiences and interactions to ensure there is a good fit.[9]

Conclusion

Monitoring, screening and evaluating children is both necessary and takes time and practice. Rather than waiting until there is a major concern, intentional teachers should conduct observations on a regular basis to closely monitor each child’s development. By watching children, we can find patterns. Once we understand the patterns, we can better understand why children do what they do, and ideally, we can create an inclusive learning environment that meets the needs of all our children. Understanding that over half of the children in your classroom may potentially have some special need, disability, delay or impairment is crucial. Recognizing that unless we observe regularly, we won’t be able to refer families in a timely manner to get the support services and professional help that they need is essential. Research tells us that children who receive early intervention are more likely to master age-appropriate developmental milestones, have increased academic readiness and are more apt to socialize with their peers. It is important to remember that everyone in the classroom, including teachers, assistants and directors and supervisors, should be involved with monitoring a child’s development. As you continue to read this text, you will discover how observations are essential in planning effective curriculum, documenting children’s learning, assessing development and communicating with families.[10]

Resources to Explore

Developmental Screening: Developmental Monitoring. by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC].

Image Credits

Spiske M. (2017, January 19). Unsplash. https://unsplash.com/photos/OO89_95aUC0

Chapter Attribution

Adapted from Chapter 10: The Purpose, Process and Practice of Monitoring, Screening and Evaluating by Gina Peterson and Emily Elam in Infant & Toddler Development published by Northeast Wisconsin Technical College under a CC BY License.

- Government of Ontario 2016 ↵

- Arim et al. 2017; Lamsal et al. 2018; Zwicker et al. 2017 ↵

- Berrigan, P., Scott, C.W.M. & Zwicker, J.D. Employment, Education, and Income for Canadians with Developmental Disability: Analysis from the 2017 Canadian Survey on Disability. J Autism Dev Disord 53, 580–592 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04603-3 ↵

- Squires, J., Nickel, R., & Eisert, D. (1996). Early detection of developmental problems: Strategies for monitoring young children in the practice setting. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 17(6), 410-427. ↵

- Development Milestones charts copied from: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]. (n.d.). CDC’s Developmental Milestones. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/actearly/milestones/index.html ↵

- Teachings in Education. (2017, September 25). Antecedent Behavior Consequence: ABC Charts & Model. YouTube [Video]. https://youtu.be/UVKb_BXEp5U ↵

- Washington State Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction. (2008). A Guide to Assessment in Early Childhood: Infancy to Age Eight. http://www.k12.wa.us/EarlyLearning/pubdocs/assessment_print.pdf ↵

- Division for Early Childhood (DEC) and the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC). (April 2009). Early Childhood Inclusion. https://www.naeyc.org/sites/default/files/globally-shared/downloads/PDFs/resources/position-statements/ps_inclusion_dec_naeyc_ec.pdf. ↵

- Morin, A. (2020). Least Restrictive Environment (LRE): What You Need to Know. https://www.understood.org/en/school-learning/special-services/special-education-basics/least-restrictive-environment-lre-what-you-need-to-know ↵

- The Early Learning Institute. (2018). Top 5 Benefits of Early Intervention. https://www.telipa.org/top-5-benefits-early-intervention/ ↵