2.4 Frameworks to Inform Your Entrepreneurial Path

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Identify common frameworks used to shape an entrepreneurial venture

- Compare how some frameworks better fit certain venture types

- Define an action plan and identify tools available for creating an action plan

- Describe some common types of entrepreneurs

In designing a venture that is sustainable or capable of being self-funded, it is helpful to use specific tools to manage information. One such tool is a framework—a structure or outlined process that can be used to accomplish entrepreneurial goals through problem solving, idea generation and validation, and brainstorming.

Selecting a Framework

You can choose any of several popular frameworks to help with the design and integration of your business experience and entrepreneurial thinking. The most widely used frameworks that have been developed as integrative tools to support entrepreneurial thinking include:

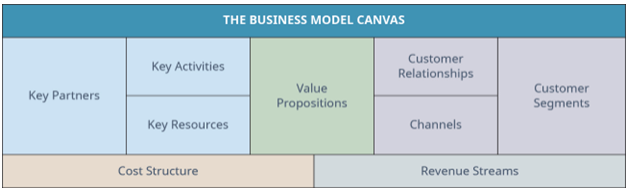

Business Model Canvas (BMC) offers a simple, one-page tool used to design an innovative business model that can be presented to key stakeholders (Figure 2.22). The business model canvas is discussed more fully in Business Model and Plan.

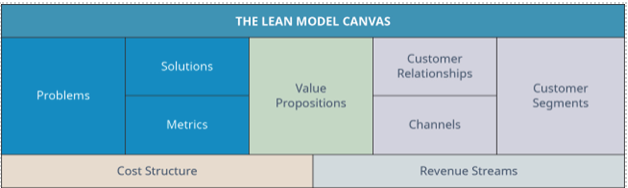

Lean Strategy Canvas is a spinoff of the BMC that introduces a potential customer feedback loop for continuous product or idea improvement to meet the market’s needs (Figure 2.23). The lean strategy canvas is discussed more fully in Launch for Growth to Success.

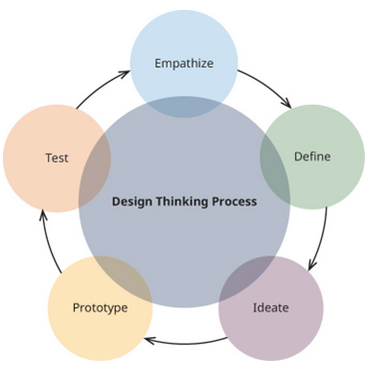

Design Thinking Process supports a systematic, logical approach for addressing and solving problems with multiple solutions (Figure 2.24). Design thinking was first applied in relation to STEM fields—science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. Due to the success of this process, design thinking has become popular in many other areas.

Design thinking approaches problem solving or the creation of a new venture from the perspective of the customer. For example, Amazon provides easy-to-open packages after observing the challenges customers had in opening the delivered products. Design thinking is covered in greater detail in Problem Solving and Need Recognition Techniques with applications to starting an entrepreneurial venture, product design, and improvements to existing products.

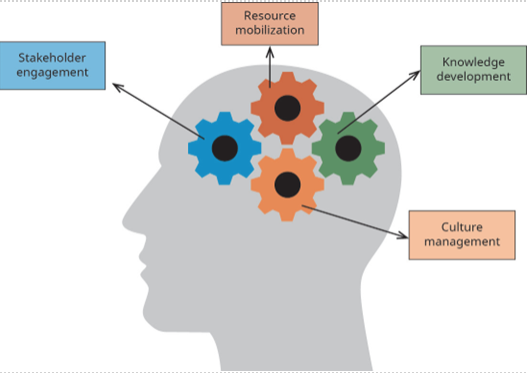

Four Lenses Strategic Framework is used for the development of social enterprises; assesses four strategic areas (stakeholder engagement, resource mobilization, knowledge development, and culture management) to address a social problem and provide sustainable social impact (Figure 2.25).

The typical application of each framework is shown in Table 2.3. The process of selecting the most appropriate framework for your entrepreneurial interests might help you understand how to develop your idea. We recommend that you try all four frameworks before selecting one. Even though each framework is identified for a general class of venture, each one provides a different perspective for developing your venture.

Frameworks

| Framework | Description | Typical Use |

|---|---|---|

| Business Model Canvas | A one-page tool that maps out nine basic building blocks that are necessary for a successful business model | Helps prepare a sustainable business model |

| Lean Startup | Outlines a quick feedback loop through customer input | Used for fast-paced industries and quick idea validation |

| Design Thinking Process | Outlines a systematic, results-oriented process to address and solve problems | Used for the development of STEM fields with expansion into entrepreneurial ventures, products, and processes; applicable to all areas |

| Four Lenses Strategic Framework | A practitioner-driven model that considers four perspectives to support and develop a client-focused ecosystem | Used for the development of social ventures |

Applying the Framework through an Action Plan

At some point during your venture development process, it becomes critical to capture your thoughts and intentions in a meaningful and productive way. Creating a customized action plan—an organized, step-by-step outline or guide that pulls together the ideas, thoughts, and key steps necessary to help set the stage for entrepreneurial success—at an early stage will make the entrepreneurial process much smoother and potentially more successful in the long run. Applying an appropriate framework will provide you with a visible, tangible, strong foundation for your future venture. In completing the framework, you should identify gaps as well as ideas for further development, then add both to your action plan. Just as you can choose from several types of frameworks, you can apply any of a variety of action plans. This section introduces some widely used action-planning tools but is not exhaustive. These selected action plans are presented as a way to jumpstart your thinking for the venture creation process.

Action Plans

You may have heard stories about potential entrepreneurs who hesitated to start a venture, largely out of fear of creating a business plan. Historically, business plan creation has required significant amounts of time, resources, and research. Although business plans are still enormously valuable, some useful business-plan-like tools have emerged: These are essentially variations on the development, content, and structure of a traditional business plan or one of its components. One other concern about business plans is how entrepreneurs use them once they are completed. In many cases, when the venture is launched, the entrepreneurial team discovers that the business plan does not reflect the realities that the team faces. A wide range of variables can often negate the value of the business plan. The true benefit of completing the business plan is that it forces the entrepreneurial team to think through their decisions as reflected in the plan. Even if the venture and the business plan change, the process of creating the business plan encourages critical thinking and improved decisions. In real time, you will need to make changes to your business plan and your venture. Throughout the venture’s life span, you should continue your background research and projections to adapt the business plan.

Unlike with the business plan, the purpose of an action plan is to pull together the ideas, thoughts, and actions necessary to help you set the stage for entrepreneurial success. Consider what kind of action plan you need to prepare a holiday meal. We have a vision of the end result—friends and family gathered together to share a delicious, festive meal. We will need to select the right location for the holiday meal, identify the guests to invite, and create a financial budget for the related costs of the holiday meal. Then we would need to create our action plan—similar to a business plan—to identify what actions are necessary to support the event. In our action plan, we would include inviting guests to the event, drawing up a menu and a grocery list, designing a timeline to ensure that all the dishes of the holiday meal are completed in the correct sequence: We want all the food to be ready at the right time. Our action plan would also include the clean-up process and any after-dinner activities that we want at our event. As you can see, both the business plan and the action plan are necessary for success.

Once you select a framework and an action plan, you have the basic tools and information you need to outline the path of your venture. The framework offers a big picture of what you want to create and the resources required for that goal, whereas the action plan provides you with concrete actions for starting along your entrepreneurial path and, later, for supporting the business plan.

Action plans can also result from using the tools listed in Table 2.4. These tools can help you visualize the process necessary to reach your end goal by clarifying the necessary actions. They are also tangible guidelines for innovating, exploring, and creating solutions to entrepreneurial problems or opportunities. You might also use your action plan to get “unstuck” during any challenging phase of the entrepreneurial process. One word of caution regarding these tools: You need to use them to get results. So be sure you are realistic about your interests, abilities, and availability when you create your plans. For example, wireframing is a technique for webpage design used early in the development process in which content, layout, and functionality are identified prior to the actual creation of the webpage. Coincidentally, this is another application of design thinking through the focus on the end user’s interaction with the website. As you can see from this example, searching for popular tools used within specific industries will provide you with support in building your framework. Table 2.4 provides a few examples of action planning tools that are used to delve into the specific topic.

| Tool | Description | Use |

|---|---|---|

| Vision or Dream Board | A visual tool to present the ideal situation that you are working towards achieving | Wireframing |

| Storyboard | A scene-by-scene visual of the activity process from start to finish | Downloading method (IDEO) |

| Mind map | A visual tool that assists with categorizing brainstorming types of ideas | Brainstorming |

| Hypothesis | A proposition or statement as a basis for further testing or investigating | Interviewing |

| Logic Map | Visual representation of relationships between various components or variables | Questionnaires |

The action plan support tools presented in Table 2.4 are a sample list of representative tools that are useful in motivating, inspiring, identifying, and clarifying needed actions. This list is not exhaustive; if you have something that works for you, then use it. Several apps are also available to help you capture ideas to create action plans, as shown in the Suggested Resources. The idea is to find and use a visual or tangible tool that inspires you to get focused, organized, and committed to taking the actions necessary to turn your entrepreneurial dream into a reality. Let’s say you know that you want to start a venture that helps people recover after some type of disaster. You could use one of these action plan support tools, such as a mind map, to help you brainstorm possible needs resulting from a disaster in a city (Figure 2.26). You can categorize the ideas to help people and animals, or to repair the city’s infrastructure. After completing the mind map, you would then consider which areas fit your interests, passions, and skills. From this point, you could identify the type of venture you want to create and the necessary actions to move forward with your idea. Using these types of tools assists in identifying actions that need to be addressed in your action plan.

Types of Entrepreneurs

Recall from The Entrepreneurial Perspective that for some people, the entrepreneurial pathway is clear cut and logical. For example, a career in a biomedical lab may involve research and clinical trials that lead to patent applications for a product to sell in the marketplace, leading to a new venture. Others experience the entrepreneurial pathway through nontraditional methods, as when an unexpected opportunity arises. As the global marketplace continues to evolve, new entrepreneurial opportunities will open for individuals who are open to opportunities that build on creativity and innovation.

Traditional entrepreneurs were perceived as individuals who did not fit in a typical organizational structure or as people who had the brains, creativity, imagination, and money to launch out on their own. However, this perception is changing with increasing support to reduce barriers to enable access to entrepreneurship for all demographic groups. According to a 2018 Capitol Hill discussion on women, minorities, and entrepreneurship, the current entrepreneurial demographics show that only 12 percent of US innovators are women and that US-born minorities accounted for 8 percent, with African Americans making up only one-half of 1 percent of this group.[1] According to a National Academies of Sciences report, as cited in the same Capitol Hill discussion, women- and minority-owned small businesses received less than 16 percent of all Small Business Innovation Research (SBIT) program awards. Even though women account for 51 percent of the US population and own 29 percent of businesses, they received only 6 percent of SBIT awards.

Also cited at the Capitol Hill briefing, a 2015 report by the US Department of Commerce showed that women-owned small businesses have a 21 percent lower rate of winning federal contracts. One result from this Capitol Hill briefing was the passage of the Promoting Women in Entrepreneurship Act to require the National Science Foundation to encourage entrepreneurial programs to recruit and support women in commercial activities rather than purely laboratory-based activities. Some of the challenges identified in this discussion for groups other than the traditional entrepreneurs described include life choices such as childbearing, access to funding, and lack of support and follow-through to support women and minorities in their interests related to potential entrepreneurial activities.

Other findings drawn from the Census Bureau data and reported by the Kauffman Foundation found that over 70 percent of Asian, Hispanic, and African American entrepreneurs relied on personal and family savings as their main source of startup capital. Women also face challenges in funding, receiving just 2.2 percent of venture capital funding in 2018.[2] A bill called the Support Startup Businesses Act, reintroduced in the US Senate in 2019, would address these challenges by increasing overall funding to help startups, creating more flexibility in funding, and expanding services for startups.[3] The panelists ended the Capitol Hill discussion by noting that “bro culture” has proliferated at the expense of women- and minority-based entrepreneurial ideas. Cultural barriers, including historical disenfranchisement of women, minorities, and immigrants, arise from biases, with one speaker noting that investors ask more difficult and probing questions of male entrepreneurs but pose more skeptical questions to women.

Today, opportunities have expanded for businesses and organizations that respond to current challenges, which may include trying to improve a negative situation or finding a need in a positive situation, with an increasing awareness of the benefits provided through entrepreneurial activities. As more global, cultural, and economic issues and opportunities arise, more individuals will explore entrepreneurship as a response to these challenges. For example, noting the challenges that women and minorities face in starting a new venture, Alan Donegan and his team train people on how to turn their entrepreneurial visions into a reality through his PopUp Business School. The point is that opportunities should be available to everyone, as long as we keep an open mind when considering how change contributes to new venture creation.

What Can You Do?

Barriers to Funding

Given this list of cultural factors and economic factors, what can you do to assist in solving the challenges related to biases? Consider how Alan Donegan’s responded to the need to educate people on how to start their own business. He created a company to address this need. You may also consider reading statistical information such as census data and news reports to identify unique target markets and potential needs that could result in a new venture.

The Kauffman Foundation reports these issues, summarized in Table 2.5.

Potential Barriers to Entrepreneurial Funding[4]

| Potential Barrier | Challenges |

|---|---|

| Geographical barriers | Close to 80 percent of about $21.1 billion in venture-capital funding in the first quarter of 2018 was disbursed in five regional clusters—San Francisco (North Bay Area), Silicon Valley (South Bay Area), New England, New York City metro, and LA/ Orange County—with slightly more than 44 percent in the North and South Bay Areas. |

| Gender bias | Women are substantially less likely to start businesses than men. In 1996, the rate of new entrepreneurs for women was 260 per 100,000 people, compared to 380 per 100,000 for men. In 2017, the rate of new entrepreneurs for women was 270 per 100,000, compared to 400 per 100,000 for men. This reflects new entrepreneurs, regardless of incorporation or employer status. |

| Racial and ethnic bias | The landscape of entrepreneurship in the United States is marked by significant differences across racial and ethnic groups. Minority-owned firms are found to face significant barriers to capital. For example, minority-owned firms are disproportionately denied when they need and apply for additional credit. One study compared sources of finance and found that new businesses owned by Black people start with almost three times less in terms of overall capital than new businesses owned by White people, and that this gap does not close as firms mature. |

| Lack of initial wealth | Low-income individuals without initial (pre-existing) wealth also face significant barriers to capital. Research on liquidity constraints showed that the top ninety-fifth percentile of wealthy individuals in the United States is more likely to start businesses than other income groups, and that personal and household wealth are important drivers of entry. Research at the neighborhood level found that in New York City, the richer third of neighborhoods had more than twice the rate of self-employment than the poorest third. A higher household net worth of a founder is linked to larger amounts of external funding received, even after accounting for human capital, venture characteristics, and demand for funds. |

| Shift in the banking industry | Large banks have become larger, while there are fewer small and medium-size banks. Larger banks survived the Great Recession with balance sheets restored, while small banks—the ones more likely to lend to entrepreneurs—were limited by both economic conditions and new regulatory barriers |

| Information asymmetry | The persistence of information asymmetry in capital markets between the supply of capital (investors) and the demand for capital (entrepreneurs) gives rise to barriers faced by entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurs face a larger challenge than established businesses in accessing capital because established businesses can leverage their longer track records and existing relationships. |

Questions

- What challenges do you face in these areas?

- What steps might you take to help mediate those challenges?

As the traditional view of entrepreneurship evolves, different types of entrepreneurship are emerging and are worth noting as you contemplate your entrepreneurial journey. The types presented here are among the most common today, each with its own unique opportunities and challenges.

- College Entrepreneur: As the cost of higher education continues to rise, more college students are seeking ways to reduce reliance on tuition loans by launching a venture. The college entrepreneur might launch an enterprise while attending or after graduating from college. Entrepreneurship courses might require a student to create and launch a venture as part of the curriculum, and this can turn into an actual earnings opportunity.

- Corporate Intrapreneur: If you work for a progressive company that seeks innovative solutions for growth and opportunities, you can become an intrapreneur by organizing the necessary resources to pursue a venture of organizational interest.

- Franchise Entrepreneur: Since a franchise grants a license to an entrepreneur to trade under the franchise’s name, a franchise entrepreneur gains a head start in an industry by launching the franchise.

- Immigrant Entrepreneur: With increasing global unrest, more immigrants are traveling to new countries. In the United States, ethnic communities of immigrants welcome their compatriots and assist them in becoming independent through entrepreneurship. These communities pool together the necessary resources to support the new immigrant until the business is self-sustaining.

- Internet Entrepreneur: As access to technology and its related platforms increases, so do opportunities for Internet-based businesses. Internet entrepreneurs utilize social media platforms, smartphones and tablets, applications (apps), and any other form of accessible technology as their product or venture. The critical structure for these ventures is the inclusion of an e-commerce or online payment processing capability.

- Woman or Minority Entrepreneur: Women have a unique perspective and potential to capitalize on new or already existing niches in many entrepreneurial fields. Many cultural groups, such as Haitians, Cubans, or Jamaicans, also have unique marketplace skills and demands.

- Part-time Entrepreneur: In response to economic downturns, underemployment, and unemployment, more individuals are supplementing income through part-time activities, casually referred to as “side hustles.” These individuals may launch businesses through multilevel marketing firms, such as Avon, Mary Kay, Stella & Dot, and others. This category may also include self-employed freelancers. Examples include writers, graphic designers, artists, web developers, and massage therapists.

- Social Entrepreneur: Some entrepreneurs are driven to offer innovative solutions to existing and emerging social problems, such as poverty, hunger, human trafficking, and environmental degradation. Most social enterprises are structured as nonprofit entities. However, increased interest in for-profit entities that marry business and social goals has given rise to a subcategory has emerged known as a B-corp (see Business Structures Options: Legal, Tax, and Risk Issues), or benefits corporation. The B-corp designation is a voluntary certification that is managed by the nonprofit group B Lab to ensure that corporations adhere to specific guidelines, rules, and accountability.

- Information Technology & Innovation Foundation. “Promoting diversity in entrepreneurship.” 2018. https://itif.org/events/2018/03/07/promoting-diversity-entrepreneurship ↵

- Emma Hinchliffe. “Funding for Female Founders Stalled at 2.2% of VC Dollars in 2018. Fortune. January 28, 2019. https://fortune.com/2019/01/28/funding-female-founders-2018/ ↵

- Jason Rittenberg. “Startup Act Reintroduced Innovation Support.” State Science & Technology Institute (SSTI). January 31, 2019. https://ssti.org/blog/startup-act-reintroduced-would-expand-federal-innovation-support ↵

- Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation. Access to Capital for Entrepreneurs: Removing Barriers. April 2019. https://www.kauffman.org/-/media/kauffman_org/entrepreneurship-landing-page/capital-access/capitalreport_042519.pdf ↵