5 Leadership and Your Emotions

Chad Flinn and Tim Carson

Learning Objectives

In this chapter, you will be introduced to the importance and influence of emotions, especially as they affect how people lead and how people work.

This chapter will help you:

- Identify the connection and relationship between leadership development and emotions.

- Catagorize emotional intelligence competencies.

- Discover how emotions affect attitudes and behaviours at work.

Leadership Development and Emotions

In the previous chapter, you were introduced to several characteristics and styles of leadership. Competencies are often used to describe those attributes which are most desirable for leaders in almost any industry or profession.

However, these styles should not be developed in isolation and at various times they are used in conjunction with other competencies. Over the past decade, there has been an upward trend in understanding the role, influence, and application of different intelligence. Most likely, you are familiar with the intelligence quotient (IQ). There are many more than this and some scholars would argue there are as many as nine different types of intelligences.

Some would argue there are as many as nine different types of intelligence. These range from visual, mathematical, linguistic, and kinesthetic. Although these are mostly related to how the individual relates to the external world, there is one which directly relates to the effectiveness of leadership development and application. Both as interpersonal (relationships between people) and intrapersonal (awareness of something within oneself). Emotional intelligence would be such an example.

Emotional intelligence (EQ) can be summarized as the ability to recognize and manage one’s own emotions as well as recognize and manage the emotions of others. Figure 1 is an example of a common matrix for emotional intelligence. The left side of the diagram pertains to becoming more self-aware while the right side would pertain to becoming other-aware. This diagram illustrates that before a leader can begin managing emotions, one must first become aware or recognize emotions.

This figure also illustrates that fundamentally, recognizing emotions either in yourself or in others, is only the first step in becoming an effective leader. The next task is to begin regulating how those emotions affect not only personal outcomes but the outcomes of initiatives within teams or organizations.

Recognizing your emotions is the ability to accurately assess your own emotions in the context of any situation and understand how those emotions inform your attitudes and actions. This would be described by some authors as becoming more self-aware.

Managing your emotions is what you do after you recognize how you are internally responding to your environment. Managing emotions includes active and passive responses. If you choose not to act on your emotions that is still an exercise in emotional management. Managing your emotions is also not about you burying them down inside yourself once you notice them. At the heart of managing your emotions is your ability to couple the practice of recognizing your emotions and directing your behaviour in a positive direction.

Recognizing emotions in others is the ability to accurately discern the emotions in other people and understand what is going on with them in their context. This would mean that perceiving what other people are thinking and feeling is vitally important. Even if you don’t think or feel the same way.

Managing the emotions of others is the final zone and often time the most difficult zone to navigate within. Yet it also yields the most results when working with others, whether that is in a team or across disciplines. Managing emotions in others are not so much about controlling others rather it is the ability to use your awareness of yourself and others to successfully manage your interactions.

Key Takeaways

Emotional Intelligence Competencies

The following list is not meant to be an exhaustive list of competencies you need in order to become an expert in the topic of emotional intelligence. Rather, they are provided as a means to highlight the skills needed to become a better leader. It is widely recognized that emotional intelligence plays a key role in leading others well. Indeed, gaining credibility, trust, and confidence one would do well to continually work on improving these competencies.

Self-Awareness

Knowing one’s strengths, weaknesses, motivators, values, and influence upon others. One who possesses a healthy self-awareness is usually self-confident, realistic, and seeks constructive criticism.

Self-Control

Recognizing, controlling and regulating disruptive impulses, moods, or thoughts. A self-controlled person has been shown to increase trust and integrity with others and is comfortable with some ambiguity and change.

Transparency

Transparency as a value is about being open, honest, visible, and accessible. When a leader is working to be transparent, the road to achieving initiatives and goals is paved with trust. Trust is the fundamental building blocks in any relationships. If a leader wants to see success in her constituents and within herself, then trust is the essential ingredient. Transparency assists in building that trust.

Adaptability

The ability to effectively react and respond in constructive ways to situations is known as adaptability. Some have defined adaptability as the leader’s capacity to regulate their emotional responses to new or uncertain circumstances. Being adaptive entails the leader to think, modify their behaviours, and regulate emotions when facing uncertain circumstances.

Empathy

Accurately recognizing and understanding other people’s emotional situations. Being considerate of other’s opinions when making decisions, those with empathy tend to attract, retain and develop others more successfully.

Influence

For leaders to have influence, in either a positive or negative direction, is to have an impact on their constituent’s thoughts, attitudes, choices, and behaviours. Although there is inherent power in influence, leaders should be cautious in exercising it as a control mechanism upon their constituents. Rather, influence is about noticing what motivates people’s commitments and using that knowledge to leverage positive results for constituents first.

Collaboration

Building rapport with individuals and/or teams to assist in helping them move forward to accomplish tasks or goals. A collaborator seeks to be persuasive and flexible, especially when working in teams. They seek opportunities for networking and building their expertise in leading change, especially through teams.

Emotions Affect Attitudes and Behaviors at Work[1]

Emotions shape an individual’s belief about the value of a job, a company, or a team. Emotions also affect behaviors at work. Research shows that individuals within your own inner circle are better able to recognize and understand your emotions (Elfenbein & Ambady, 2002).

So, what is the connection between emotions, attitudes, and behaviors at work? This connection may be explained using a theory named Affective Events Theory (AET). Researchers Howard Weiss and Russell Cropanzano studied the effect of six major kinds of emotions in the workplace: anger, fear, joy, love, sadness, and surprise (Weiss & Cropanzano, 1996). Their theory argues that specific events on the job cause different kinds of people to feel different emotions. These emotions, in turn, inspire actions that can benefit or impede others at work (Fisher, 2002).

Figure 7.11

According to Affective Events Theory, six emotions are affected by events at work.

For example, imagine that a coworker unexpectedly delivers your morning coffee to your desk. As a result of this pleasant, if unexpected experience, you may feel happy and surprised. If that coworker is your boss, you might feel proud as well. Studies have found that the positive feelings resulting from work experience may inspire you to do something you hadn’t planned to do before. For instance, you might volunteer to help a colleague on a project you weren’t planning to work on before. Your action would be an affect-driven behavior (Fisher, 2002). Alternatively, if you were unfairly reprimanded by your manager, the negative emotions you experience may cause you to withdraw from work or to act mean toward a coworker. Over time, these tiny moments of emotion on the job can influence a person’s job satisfaction. Although company perks and promotions can contribute to a person’s happiness at work, satisfaction is not simply a result of this kind of “outside-in” reward system. Job satisfaction in the AET model comes from the inside-in—from the combination of an individual’s personality, small emotional experiences at work over time, beliefs, and affect-driven behaviors.

Key Takeaways

Emotional Labor

Negative emotions are common among workers in service industries. Individuals who work in manufacturing rarely meet their customers face-to-face. If they’re in a bad mood, the customer would not know. Service jobs are just the opposite. Part of a service employee’s job is appearing a certain way in the eyes of the public. Individuals in service industries are professional helpers. As such, they are expected to be upbeat, friendly, and polite at all times, which can be exhausting to accomplish in the long run.

Humans are emotional creatures by nature. In the course of a day, we experience many emotions. Think about your day thus far. Can you identify times when you were happy to deal with other people and times that you wanted to be left alone? Now imagine trying to hide all the emotions you’ve felt today for 8 hours or more at work. That’s what cashiers, school teachers, massage therapists, fire fighters, and librarians, among other professionals, are asked to do. As individuals, they may be feeling sad, angry, or fearful, but at work, their job title trumps their individual identity. The result is a persona—a professional role that involves acting out feelings that may not be real as part of their job.

Emotional labor refers to the regulation of feelings and expressions for organizational purposes (Grandey, 2000). Three major levels of emotional labor have been identified (Hochschild, 1983).

- Surface acting requires an individual to exhibit physical signs, such as smiling, that reflect emotions customers want to experience. A children’s hairdresser cutting the hair of a crying toddler may smile and act sympathetic without actually feeling so. In this case, the person is engaged in surface acting.

- Deep acting takes surface acting one step further. This time, instead of faking an emotion that a customer may want to see, an employee will actively try to experience the emotion they are displaying. This genuine attempt at empathy helps align the emotions one is experiencing with the emotions one is displaying. The children’s hairdresser may empathize with the toddler by imagining how stressful it must be for one so little to be constrained in a chair and be in an unfamiliar environment, and the hairdresser may genuinely begin to feel sad for the child.

- Genuine acting occurs when individuals are asked to display emotions that are aligned with their own. If a job requires genuine acting, less emotional labor is required because the actions are consistent with true feelings.

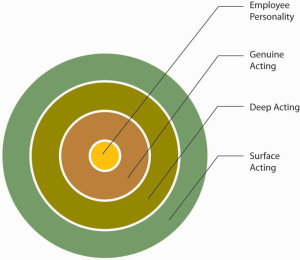

Figure 7.12

When it comes to acting, the closer to the middle of the circle that your actions are, the less emotional labor your job demands. The further away, the more emotional labor the job demands.

Research shows that surface acting is related to higher levels of stress and fewer felt positive emotions, while deep acting may lead to less stress (Beal et al., 2006; Grandey, 2003). Emotional labor is particularly common in-service industries that are also characterized by relatively low pay, which creates the added potentials for stress and feelings of being treated unfairly (Glomb, Kammeyer-Mueller, & Rotundo, 2004; Rupp & Sharmin, 2006). In a study of 285 hotel employees, researchers found that emotional labor was vital because so many employee- customer interactions involve individuals dealing with emotionally charged issues (Chu, 2002). Emotional labor- ers are required to display specific emotions as part of their jobs. Sometimes, these are emotions that the worker already feels. In that case, the strain of the emotional labor is minimal. For example, a funeral director is generally expected to display sympathy for a family’s loss, and in the case of a family member suffering an untimely death, this emotion may be genuine. But for people whose jobs require them to be professionally polite and cheerful, such as flight attendants, or to be serious and authoritative, such as police officers, the work of wearing one’s “game face” can have effects that outlast the working day. To combat this, taking breaks can help surface actors to cope more effectively (Beal, Green, & Weiss, 2008). In addition, researchers have found that greater autonomy is related to less strain for service workers in the United States as well as France (Grandey, Fisk, & Steiner, 2005).

Key Takeaways

You’ll experience discomfort or stress unless you find a way to alleviate the dissonance. You can reduce the personal conflict by changing your behavior (trying harder to act polite), changing your belief (maybe it’s OK to be a little less polite sometimes), or by adding a new fact that changes the importance of the previous facts (such as you will otherwise be laid off the next day). Although acting positive can make a person feel positive, emotional labor that involves a large degree of emotional or cognitive dissonance can be grueling, sometimes leading to negative health effects (Zapf, 2006).

References

Beal, D. J., Green, S. G., & Weiss, H. (2008). Making the break count: An episodic examination of recovery activities, emotional experiences, and positive affective displays. Academy of Management Journal, 51, 131–146.

Beal, D. J., Trougakos, J. P., Weiss, H. M., & Green, S. G. (2006). Episodic processes in emotional labor: Perceptions of affective delivery and regulation strategies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 1053–1065.

Bradberry, T., Greaves, J. (2009). Emotional Intelligence 2.0. San Diego: TalentSmart

Carmeli, A. (2003). The relationship between emotional intelligence and work attitudes, behaviors and outcomes. Journal of Managerial Psychology,18(3), 788-813.

Chu, K. (2002). The effects of emotional labor on employee work outcomes. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University.

Collie, R.J, & Martin, A.J. (2016). Adaptability: An important capacity for effective teachers. Educational Practice and Theory, 38(1), 27-39

Covey, Stephen M. R. and Merrill Rebecca R. 2006. The Speed of Trust: The One Thing That Changes Everything. New York, NY: Free Press

Elfenbein, H. A., & Ambady, N. (2002). Is there an in-group advantage in emotion recognition? Psychological Bulletin, 128, 243–249.

Fisher, C. D. (2002). Real-time affect at work: A neglected phenomenon in organizational behaviour. Australian Journal of Management, 27, 1–10.

Glomb, T. M., Kammeyer-Mueller, J. D., & Rotundo, M. (2004). Emotional labor demands and compensating wage differentials. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89, 700–714.

Grandey, A. (2000). Emotional regulations in the workplace: A new way to conceptualize emotional labor. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5, 95–110.

Grandey, A. A. (2003). When “the show must go on”: Surface acting and deep acting as determinants of emotional exhaustion and peer-rated service delivery. Academy of Management Journal, 46, 86–96.

Grandey, A. A., Fisk, G. M., & Steiner, D. D. (2005). Must “service with a smile” be stressful? The moderating role of personal control for American and French employees. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 893-904

Goleman, D., Boyatzis, R., McKee, A. (2013). Primal Leadership: unleashing the power of emotional intelligence. Boston: Harvard Business Review Press

Goleman, D. (2015). What makes a leader? In HBR’s 10 must reads, On emotional intelligence (pp. 1-21). Boston: Harvard Business Review Press.

Harms, P.D., Crede, M. (2010). Emotional intelligence and transformational and transactional leadership: a meta-analysis. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 17(1), 5-17.

Lee, R. T., & Ashforth, B. E. (1996). A meta-analytic examination of the correlates of three dimensions of job burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81, 123-133

Lewandowski, C. A. (2003, December 1). Organizational factors contributing to worker frustration: The precursor to burnout. Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare, 30, 175-185

Maslach, C. (1982). Burnout: The cost of caring. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall

Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1981). The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Occupational Behavior, 2, 99-113

Mills, L.B., (2009). A meta-analysis of the relationship between emotional intelligence and effective leadership. Journal of Curriculum and Instruction 3(2), 22-38.

Rupp, D. E., & Sharmin, S. (2006). When customers lash out: The effects of customer interactional injustice on emotional labor and the mediating role of discrete emotions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 971-978

Yukl, G. (2013). Leadership in organizations (8th ed.). Boston: Pearson.

Weiss, H. M., & Cropanzano, R. (1996). Affective events theory: A theoretical discussion of the structure, causes and consequences of affective experiences at work. Research in Organizational Behavior, 18, 1-74

Zapf, D. (2006). On the positive and negative effects of emotion work in organizations. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 15, 1-28

[1] Organizational Behaviour – UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA LIBRARIES PUBLISHING EDITION, 2017. THIS EDITION ADAPTED FROM A WORK ORIGINALLY PRODUCED IN 2010 BY A PUBLISHER WHO HAS REQUESTED THAT IT NOT RECEIVE ATTRIBUTION.