16.1 Media and Society

William Little and Ron McGivern

The Bias of Communication

Forms of communication and media have a powerful role in the way societies are structured. Oral cultures that pass stories and history down by way of mouth produce different societal structures than cultures which communicate through symbols and languages imprinted in stone or clay. Both types of culture differ from societies that communicate through writing on paper. The dominant media used to communicate in a society is profoundly linked to its material foundations of life, time, and space.

In his 1951 book, The Bias of Communication, the Canadian historian Harold Innis (1894–1952) argued that forms of communication bias societies towards two types of configurations: time-binding societies or space-binding societies. The bias of communication in this sense refers to how a form of communication orients the institutional framework of a society toward either the control of time or the control of space (Innis, 1951).

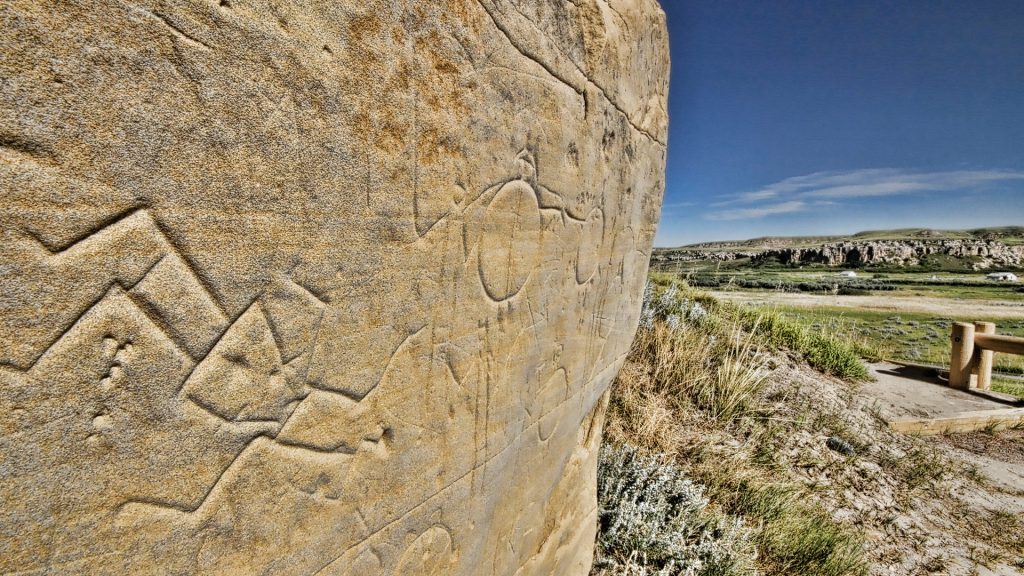

Time-biased media were forms of communication that sought to transcend or “bind” time. They were imprinted into durable materials like clay or stone which had long lifespans and were difficult to transport, such as Sumerian cuneiforms, Egyptian hieroglyphics, or Indigenous rock paintings (pictographs) and rock carvings (petroglyphs). Or they took the form of speech and story telling in oral culture, passing down ancestral memories, values, and traditional knowledges from generation to generation. In both cases, Innis argued, time-biased media bound the past in a continuous line to the present and future. In purely oral story telling cultures this encouraged dialogue and equality, but durable media (clay, stone, etc.) favoured hierarchical societies. The power of elite groups like the Egyptian or Babylonian priests, or the Catholic clergy of the Middle Ages, was based on their exclusive access to sacred knowledge. But both oral and durable media supported civilizations that were rooted in specific locales and based on historical continuity of local customs, rather than centralized civilizations that controlled large expanses of territory.

Space-biased media were forms of communication more suited to transmission over distances. They made it possible to transcend geographical boundaries to bind space. Historically they were printed on paper or papyrus, which were impermanent media but easily transportable, making them ideal for administrating large empires or conducting long distance trade. Innis (1950) argued for example that “the conquest of Egypt by Rome gave access to supplies of papyrus, which became the basis of a large administrative empire.” It gave the Romans and eventually modern colonial empires the ability to pass instructions along lengthy chains of communication. Writing, and later radio, television, and mass circulation newspapers, are ephemeral media that facilitate the transmission of practical administrative information (as opposed to sacred values and experiences) and the expansion of political and economic empires. They thereby supported less hierarchical, (in the sense that access to paper media was more widespread), but administratively centralized societies that extended over vast spaces.

Mass Media

The development of modern mass media such as television, radio, newspapers, and books, has different implications for the structure of societies. The term media means that the communication is not direct, or face-to-face, but mediated through the intervention of an agency or sender that produces messages and distributes them though different technologies. The term mass means that the communication is received by many people. Mass media are forms of communication that pass from a centralized location to the masses. They are one of many forms of communication.

The mass media therefore have three characteristics. First, they tend to be one way and hierarchical, (i.e., messages go from the TV studio or newspaper publisher to the audience, but not back again). Second, their messages are undifferentiated; everyone in the audience receives the same message, program, or story regardless of their location, social background, or specific interests. Finally, they are media that address a mass: a large and disperse group, lacking self-awareness and self-identity, whose members are largely unknown to one another, and who are incapable of acting together in a concerted way to achieve objectives. The masses addressed by mass media are characterized by anonymity and passivity.

This lead 20th century critics, like Horkheimer and Adorno (2002/1947), to be concerned about mass media products — TV, Hollywood movies, pop music, pulp fiction, sensationalist newspapers, etc. — that were pitched to the lowest common denominator to have the widest commercial appeal. The commercial mass media produced standardized products like the TV sitcom or the three-chord pop song that could be consumed without thought or critical reflection. They distracted audiences from real problems and created a mass culture of conformity by integrating audiences into the commercial circuit of media production and consumption. As Lowenthal (1961) put it, culture industry products are characterized by “standardization, stereotype, conservativism, mendacity [and] manipulated consumer goods.” As a result, they affirmed the power structures of society and depoliticized the audience while providing them with easy to consume pleasures, wish-fulfillments, and diversions.

But others, like C. W. Mills (1956) argued that the mass media play an important function in democracy and modern citizenship. The mass media not only address a public, but construct it in crucial respects. They extend the reach of information in large populations where people do not have direct access to sources and provide facts and opinions necessary for rational debate. A healthy functioning democracy is predicated on the electorate making informed choices and this in turn rests on the quality of information that they receive (Mwengenmeir, 2014). In this regard, modern professional news media have been described as society’s fourth estate, a watchdog that monitors the government of society by exposing excesses and corruption, and holding those in power accountable. This role in creating a public or citizenry extends to other media of popular culture like film, fashion, celebrity, and popular music where people gain access to trends, images, ideas, values, and identities.

The debate centers on whether society is like a mass or a public. Whereas communication to a mass tends to be one way and top down, like a broadcast that delivers a message to potentially millions of separate listeners, in a public there is the expectation that people will engage with and respond to information. They can and will “answer back” (Mills, 1956). This is the foundation of Habermas’ concept of the public sphere, the open “space” of public debate and deliberation in democratic societies where public opinion can be formed (See Chapter 17, Government and Politics). As Habermas puts it, “a portion of the public sphere comes into being in every conversation in which private individuals assemble to form a public body” (Habermas, 1974). The mass media provide a common framework for people in large societies to recognize and debate common issues. Is this a form of manipulation, or is this the basis of public engagement and citizenship?

Information Society

Manuel Castells (2010/1996) describes an information society as one in which the sources of economic productivity and political power are based on new information technologies (e.g., micro-electronic computers, digital communications technologies, gene editing) and the generation, processing and transformation of information. Exchange of information has always been important but in an information society technological development and information itself become fundamental drivers of social processes, productivity, and profits.

Information society is the condition for the formation of global society as a unit operating in simultaneous real time (see Chapter 10. Global Society) and the realignment of social organization towards fluid and flexible network structures. Increasingly tasks are not accomplished through bureaucratic organization but through loose networks of actors: a “specific set of linkages [are] organized ad hoc for a specific project, and dissolve/reform after the task is completed” (Castells, 1997). It is supported by the development of digital media or computer mediated communication networks. “Digital” means that messages, images or pieces of information are translated into series of digits in a computer code, which can be transmitted instantaneously through global cable, wireless and satellite networks, and reconstituted as consumable, machine-readable media (social media, email, streams, gaming, 3D printing, word/image/sound processing, etc.). This also enables communications to be stored, processed, and manipulated by mathematical operations like algorithms, encryption, and artificial intelligence.

The communication system of information societies is not characterized by the hierarchical, one-way, undifferentiated messages of the mass media, but rather “targeted messages to specific segments of audience” (Castells, 1997). For example, advertising or suggested content can be catered to the specific history of an audience member’s browses, searches, “likes” and views. Whereas the mass media communicate from the one to the many, digital media can communicate one-to-one, one-to-many and many-to-many. They are interactive media, enabling dialogues through two-way or many-way messages.

A product of this is a medium of communication or a mediascape of virtuality. The framework for local and global interaction is digitally simulated reality. If virtuality is the quality of having the attributes of something without sharing its real or imagined physical form, it is nevertheless as real as physical reality in its consequences for the conduct of everyday social life. The emotions experienced and the hours spent playing a video game or responding to trolls on social media are as real as in other activities, even if the virtual stimulus is never actualized or tangible.

Castells sums up the effects of digital media on societies:

Media are extraordinarily diverse, and send targeted messages to specific segments of audiences and to specific moods of the audiences…. Instead of a global village we are moving towards mass production of customized cottages. While there is oligopolistic concentration of multimedia groups around the world, there is at the same time, market segmentation, and increasing interaction by and among the individuals that break up the uniformity of a mass audience. These processes induce the formation of what I call the culture of real virtuality. It is so, and not virtual reality, because when our symbolic environment is, by and large, structured in this inclusive, flexible, diversified hypertext, in which we navigate every day, the virtuality of this text is in fact our reality, the symbols from which we live and communicate (Castells, 1997).

At the same time, Castells notes that digital technology is not equally distributed around the world, nor within societies. This is the aspect of the digital divide, the uneven access to the new technologies along race, class, and geographic lines. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) defines the digital divide as “the gap between individuals, households, businesses and geographic areas at different socio-economic levels with regard to both their opportunities to access information and communication technology (ICTs) and to their use of the Internet for a wide variety of activities” (OECD, 2001). As with any technological development in human society, not everyone has equal access. Technology, in particular, often creates changes that lead to ever greater inequalities. In short, the gap gets wider faster leading to not only unequal access to the dominant forms of digital communication but also a knowledge gap, an ongoing and increasing gap in information for those who have less access to technology. This process of technological stratification has led to a complicated set of questions about how to ensure better access for all.

Making Connections: Big Picture

Bias of Communication: Timeless Time and the Spaces of Flows

To return to the bias of communication theme, Innis (1951) showed how media of communication affect the meaning of time and space and how these meanings manifest in social practice and the formation of societies. Castells (1997) argues that digital media create a different relationship to time and space than the other types of historical media: they are the source of “timeless time” and “spaces of flows.”

Although Castells notes that the effect of digital media does not spread evenly and leads to new types of social exclusion, the relationship to time in information societies has fundamentally altered as processes become instantaneous, while space is reorganized on a global basis through digitally mediated linkages between distant locales.

In the era of digital media, the biological time of human life and seasonal cycles, and the measured clock time of the industrial age and mass media scheduling, collapse into the instantaneous time of nanoseconds. Digital media create the experience of time as a perpetual present or “now.” The barriers of time — the length of time it takes to do something, for example — are continually eliminated as communication becomes instant and tasks can be done in a moment through computation and artificial intelligence. The 24-hour news cycle, microblogging feeds, and streaming television are examples of how people’s media consumption has shifted away from the “morning newspaper” and competition between TV shows in “prime time” to a situation where everything is available in the “now” all of the time.

In this regard, Castells (1997) argues that time becomes “timeless” to the degree that the ordinary sequencing of time — the division of past, present, and future, or the succession of things that define time — is eliminated. Like a film in which the scenes have been shot out of order and then reassembled into a sequence or story line in the editing studio, the time of everyday procedures and processes can also be reassembled through digital technologies. In the information society, all dominant processes are reorganized around timeless time: the accumulation of capital through instantaneous financial transactions, the blurring of the lifecycle through new reproductive techniques, the restructuring of work tasks and schedules through a global division of labour and production processes, and so on.

As with time, space is also altered through digital media. The concept of a space of flows captures the way in which dominant processes like market transactions, circulation of global media, the production of knowledge, technological processes, etc. operate through electronic networks and information systems that link distant locations, bypass boundaries, and establish a pattern of uninterrupted flows information exchange. The way the world was divided up into discrete, distinct geographical locations and independent institutional units is surpassed by digitally mediated linkages of circuits and continuous flows of information. This reconfigures the space of everyday life by removing the physical dimension of space. For example, people and things still share “real time,” in the sense of interacting at the same time. They just do not have to be physically together in the same location to do so because information can flow freely between them at a distance. Thus the “space of flows is the material organization of time-sharing social practices that work through flows” (Castells, 1997).

Both timeless time and the space of flows are unevenly distributed throughout the world, leading to some characteristic sources of conflict in the information society. This is an aspect of the digital divide in access to technology. Timeless time describes the dominant economic processes and the privileged social groups who benefit from them, while most people in the world are still subject to seasonal time, biological time, and clock time. Similarly, people still live in specific places, bounded by geographical, physical, and cultural borders. However, the logic of the space of flows dominates, structures, and shapes the space of these places. Shifts in global investment can suddenly make a local industry redundant or put the price of housing beyond the means of locals to afford. Electronic networks that allow people to be employed in a central business district while working from home or in suburban satellite offices can mean that poor urban neighbourhoods or entire regions and countries are bypassed and further impoverished.

Types of Media and Technology

Technology and the media are interwoven, and neither can be separated from contemporary society. From the time the printing press was created (and even before), technology has influenced how and where information is shared. Today, it is impossible to discuss media and the ways that societies communicate without addressing the fast-moving pace of technology. Thirty years ago, if a person wanted to share news of their baby’s birth or a job promotion, they phoned or wrote letters. They might tell a handful of people, but would not call up several hundred, including their old high school chemistry teacher, to let them know. Now, by posting their big news, the circle of communication is wider than ever.

Technology creates media. The comic book a parent bought their daughter at the drugstore is a form of media, as is the movie they streamed for family night, the app they used to order dinner online, the billboard they saw on the way to get that dinner, and the news feed they read while waiting to pick up your order. Without technology, modern media would not exist.

Media and technology have evolved hand in hand, from early print to modern publications, from radio to television to social media. New media emerge constantly, changing the media landscape people move through and the mediated ways in which they are connected with others.

Print Newspaper

Early forms of print media, found in ancient Rome, were hand-copied onto boards and carried around to keep the citizenry informed. With the invention of the printing press, the way that people shared ideas changed, as information could be mass produced and stored. For the first time, there was a way to spread knowledge and information more efficiently. Many credit this development as leading to the Renaissance, the Protestant Reformation and ultimately the formation of a unique public sphere during the Age of Enlightenment. This is not to say that newspapers of old were more trustworthy than the Weekly World News and National Enquirer are today. Sensationalism abounded, as did censorship that forbade any subjects that would incite the populace.

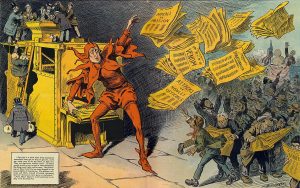

The invention of the telegraph, in the mid-1800s, changed print media almost as much as the printing press. Suddenly information could be transmitted in minutes. As the 19th century became the 20th, American publishers such as Hearst redefined the world of print media and wielded an enormous amount of power to socially construct national and world events. Of course, even as the Canadian media empires of Max Aitken (Lord Beaverbrook) and Roy Thomson or the U.S. empires of William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer were growing, print media also allowed for the dissemination of counter-cultural or revolutionary materials. Internationally, Vladimir Lenin’s Irksa (The Spark) newspaper was published in 1900 and played a role in Russia’s growing communist movement (World Association of Newspapers, 2004). Nevertheless, the flourishing working class press in Britain in the early 19th century was eliminated by the industrialization of the press and the rise of the new daily local newspaper, which required massive capital investments and profits to sustain new technology, machinery, and mass circulation (Herman and Chomsky, 2008).

With the invention and widespread use of television in the mid-20th century, newspaper circulation steadily dropped off, and in the 21st century with the advent of social media, circulation has dropped further as more people turn to internet news sites and other forms of digital media to stay informed. This shift away from newspapers as a source of information has profound effects on societies. When the news is given to a large diverse conglomerate of people, it must maintain some level of broad-based reporting and balance to appeal to them and keep them subscribing. As newspapers decline, news sources become more fractured, so that the audience can choose specifically what it wants to hear and what it wants to avoid. This creates the problem of silos and the spread of non-fact checked misinformation, which undermines the role of the public sphere in democratic decision making.

But the real challenge to print newspapers is that revenue sources are declining much faster than circulation is dropping. “Revenue from all sources, and inclusive of both “daily” and “community” papers, peaked between 2006 and 2008 at just a little over $4.8 billion. It has plunged ever since, except for … 2020 and 2021 … when a bottom of sorts seems to have been reached at $1.9 billion — forty per cent of what it was a decade-and-a-half earlier” (Winseck, 2022). Unable to compete with digital media, large and small newspapers are closing their doors across the country. Digital media has downloaded much of the costs of producing and distributing printed newspapers onto the consumer through personal technology purchases.

Television and Radio

Radio programming obviously preceded television, but both shaped people’s lives in a similar way. In both cases, information (and entertainment) could be enjoyed at home, with a kind of immediacy and community that newspapers could not offer. Prime Minister Mackenzie King broadcast the first network radio message out to the entire country in 1927 using telegraph and telephone lines to hook up the 57 private radio stations that were in operation at that time. He later used radio to promote economic cooperation in response to the international crisis of capitalism in the 1930s (McGivern, 1990).

Radio was the first “live” mass medium. People heard about the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor as it was happening. Hockey Night in Canada was first broadcast live in 1932. Even though people were in their own homes, media allowed them to share these moments in real time. Unlike newspapers, radio has unique qualities that have allowed it to survive the disruptions of the digital media era. As O’Reilly asserts, radio survives “because it is such a ‘personal’ medium. Radio is a voice in your ear. It is a highly personal activity.” He also points out that “radio is local. It broadcasts news and programming that is mostly local in nature. And through all the technological changes happening around radio, and in radio, be it AM moving to FM moving to satellite radio and internet radio, basic terrestrial radio survives into another day” (O’Reilly, 2014).

The introduction of Canadian television in the 1940s and 1950s has always reflected a struggle with the influence of U.S. television dominance, the language divide, and strong federal government intervention into the industry for political purposes. There were thousands of televisions in Canada receiving U.S. broadcasting a decade before the first two Canadian stations began broadcasting in 1952 (Filion, 1996). Public television, in contrast, offered an educational nonprofit alternative to the sensationalization of news spurred by the network competition for viewers and advertising dollars. Those sources — the CBC (Canadian Broadcasting Corporation), PBS (Public Broadcasting Service) in the United States, and the BBC (British Broadcasting Corporation) — which straddled the boundaries of public and private, garnered a worldwide reputation for quality programming and a global perspective. Al Jazeera, the publicly owned Arabic-language international news network of Qatar, has joined this group as a similar media force that broadcasts to people worldwide.

The impact of television on North American society is hard to overstate. By the late 1990s, 98% of homes had at least one television set. As of May 2022, TV reached around 85.3% of Canadians aged 2 and older every week (Stoll, 2022). All this television has a powerful socializing effect, with these forms of visual media providing reference groups while reinforcing social norms, values, and beliefs.

Film

The film industry took off in the 1930s, when colour and sound were first integrated into feature films. Unlike the private consumption of television from the home, film involves a directly communal experience: As people gathered in theatres to watch new releases, they would laugh, cry, and be scared together. Movies also act as time capsules or cultural touchstones for society. From tough-talking Clint Eastwood to the biopic of Facebook founder and Harvard dropout Mark Zuckerberg, movies illustrate society’s dreams, fears, and experiences. The film industry in Canada has struggled to maintain its identity while at the same time embracing the North American industry by actively competing for U.S. film production in Canada. Today, a considerable number of the recognized trades occupations requiring apprenticeship and training are in the film industry. While many North Americans consider Hollywood the epicentre of moviemaking, India’s Bollywood actually produces more films per year, speaking to the cultural aspirations and norms of Indian society.

Digital Media

Digital media encompass all forms of computer mediated interaction and information exchange. This usually takes place on online platforms, where one-to-one, one-to-many and many-to-many forms of mediated communication prevail. These include browsers, search engines, online shopping, social networking sites, blogs, podcasts, wikis, and virtual worlds. The list grows almost daily.

On one hand, digital media tend to break down the hierarchical structure of the mass media and level the playing field in terms of who is producing and receiving messages (i.e., creating, publishing, distributing, and accessing information) (Lievrouw and Livingstone, 2006). Digital media also offer alternative forums to groups unable to gain access to traditional political platforms, such as the groups associated with the Arab Spring protests or conspiracy theorists (van de Donk et al., 2004). On the other hand, new media are dominated by a handful of media platforms like Google, Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, and TikTok, which generate profits through selling targeted advertising space based on surveillance of users. There is also no guarantee of the accuracy of the information offered. In fact, the instantaneous communication of digital media coupled with lack of oversight and anonymity of sources means that people must be more careful than ever to ensure their news and information is coming from accurate sources.

Making Connections: Sociological Research

Just “Friend” Me: Students and Social Networking

The phenomenon known as Facebook was designed specifically for students. Whereas earlier generations wrote notes in each other’s printed yearbooks at the end of the academic year, modern technology, smart phones and the internet ushered in dynamic new ways for people to interact socially. Instead of having to meet up on campus, students could post, text, and video chat from their dorm rooms or off campus rentals. Instead of a study group gathering weekly in the library, online collaborative software and chat rooms help learners connect virtually. The availability and immediacy of computer technology has forever changed the ways students engage with each other.

Now, after several social networks have vied for primacy, a few have established their place in the market, and some have attracted niche audiences. While Facebook launched the social networking trend geared toward teens and young adults, today it is often seen as the older generation’s social media. In Canada, over 80% of Facebook users were older than aged 25 in 2022 (Dixon, 2023), whereas 43% of TikTok users were between 18 and 30 (Ceci, 2022a). The dominant social networks in Canada are Facebook (79% of social media users), YouTube (68%), Instagram (54%), TikTok (32%), and Twitter (31%) (Kunst, 2023).

These new modes of social interaction have also spawned questionable consequences, such as cyberbullying and what some call FAD, or Facebook addiction disorder (Andreassen et al., 2012). In an international study of smartphone users aged 18 to 30, 60% say they are “compulsive” about checking their smartphones and 42% admit to feeling “anxious” when disconnected; 75% check their smartphones in bed; more than 33% check them in the bathroom and 46% email and check social media while eating (Cisco, 2012). Similarly, Canadians reported spending 4.22 hours per day engaging with mobile apps in 2021 and 45% said they could not live without their smart phone (Ceci, 2022b). The most popular online activities via mobile device for Canadians were social media (42% of users), email (40%) and instant messaging (29%).

An International Data Corporation (IDC, 2012) study of 7,446 smartphone users aged 18 to 44 in the United States in 2012 found that:

- Half of the U.S. population have smartphones and of those 70% use Facebook. Using Facebook is the third most common smartphone activity, behind email (78%) and web browsing (73%).

- 61% of smartphone users check Facebook every day.

- 62% of smartphone users check their device first thing on waking up in the morning, and 79% check within 15 minutes. Among 18- to 24-year-olds the figures are 74% and 89%, respectively.

- Smartphone users check Facebook approximately 14 times a day.

- 84% of the time using smartphones is spent on texting, emailing, and using social media like Facebook, whereas only 16% of the time is spent on phone calls. People spend an average of 132 minutes a day on their smart phones including 33 minutes on Facebook.

- People use Facebook throughout the day, even in places where they are not supposed to: 46% use Facebook while doing errands and shopping; 47% when they are eating out; 48% while working out; 46% in meetings or class; and 50% while at the movies.

The study noted that the dominant feeling the survey group reported was “a sense of feeling connected” (IDC, 2012). Yet, in the international study cited above, two-thirds of 18- to 30-year-old smartphone users said they spend more time with friends online than they do in person.

All these social networks demonstrate emerging ways that people interact, whether positive or negative. Sociologists ask whether there might be long-term effects of replacing face-to-face interaction with social media. In an interview on the Conan O’Brian Show that ironically circulated widely through social media, the comedian Louis CK described the use of smartphones as “toxic.” They do not allow for children who use them to build skills of empathy, because children do not interact face-to-face or see the effects their comments have on others. Moreover, he argues, they do not allow people to be alone with their feelings. “The thing is, you need to build an ability to just be yourself and not be doing something. That’s what the phones are taking away” (NewsComAu, 2013). This is still an open question. How do social media like Facebook and TikTok and communication technologies like smartphones change the way we communicate? How could this question be studied?

Media Attributions

- Figure 16.3 Writing-on-Stone/Áísínai’pi new World Heritage Site by the Government of Alberta, via Flickr, is used under a CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 licence.

- Figure 16.4 A newspaper printing press by Newspaper Club, via Flickr, is used under a CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 licence.

- Figure 16.5 Manuel Castells in La Paz Bolivia by is used under a licence.

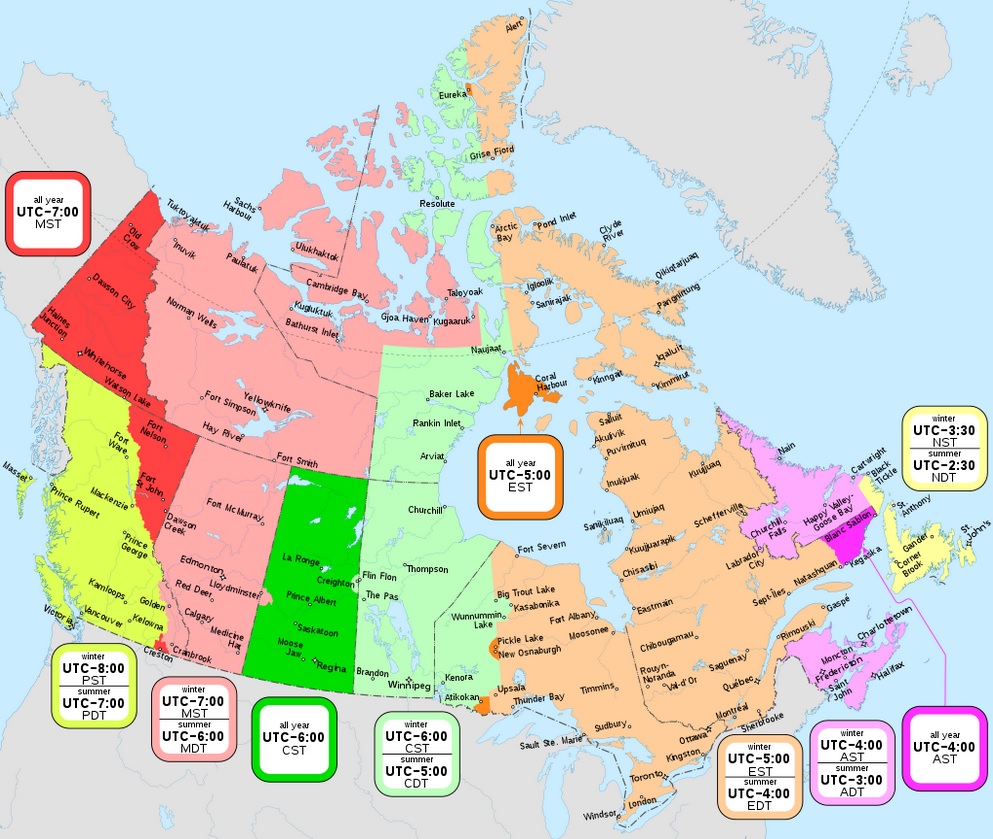

- Figure 16.6 Time zone map of Canada by MapGrid, via Wikimedia Commons, is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 licence.

- Figure 16.7 The Yellow Press, 1910 by L.M. Glackens from the Library of Congress’s Prints and Photographs division, digital ID ppmsca.27675, via Wikimedia Commons, is in the public domain.

- Figure 16.8 Facebook by Gustavo da Cunha Pimenta, via Flickr, is used under a CC BY-SA 2.0 licence.