11.5. Race and Ethnicity in Canada

When colonists came to the New World, they found a land that did not need “discovering” since it was already occupied. While the first wave of immigrants came from Western Europe, eventually the bulk of people entering North America were from Northern Europe, then Eastern Europe, then Latin America and Asia. This does not include the forced immigration of African slaves. Most of these groups underwent a period of disenfranchisement in which they were relegated to the bottom of the social hierarchy before they managed (those who could) to achieve social mobility. Today, Canadian society is multicultural, in the sense of being socially and culturally diverse, although the extent to which multiculturalism, as a practice and belief in pluralism, is embraced varies. The many manifestations of diversity carry significant political repercussions as has been discussed throughout this chapter. The sections below describe how several groups became part of Canadian society, discuss each group’s history of intergroup relations, and assess each group’s status today.

Indigenous Canadians

The only non-immigrant ethnic group in Canada, Indigenous people were once the only human inhabitants of North America (numbering approximately 2.8 to 5.7 million north of Mexico (Koch et al., 2019)), but by 2011 they made up only 4.3% of the Canadian populace (Statistics Canada, 2013).

How and Why They Came

The earliest humans in Canada arrived millennia before European immigrants. Dates of the migration are debated with estimates ranging from between 130,000 and 12,000 BCE (Steeves, 2021). It is thought that people migrated to this new land from Asia in search of big game to hunt, which they found in huge herds of grazing herbivores in the Americas. Over the centuries and then the millennia, Indigenous cultures blossomed into an intricate web of hundreds of interconnected groups, each with its own customs, traditions, languages, and religions.

History of Intergroup Relations

Indigenous cultures prior to European settlement are referred to as pre-contact or pre-Columbian: that is, prior to the coming of Christopher Columbus in 1492. Mistakenly believing that he had landed in the East Indies, Columbus named the Indigenous people “Indians:” a name that has persisted for centuries despite it being a geographical misnomer used to homogenously label over 500 distinct groups who have their own languages and traditions.

The history of intergroup relations between European colonists and Indigenous peoples is a brutal one that most Canadians are familiar with. As discussed in the section on genocide, the effect of European settlement was to nearly destroy the Indigenous population. Although Indigenous people’s lack of immunity to European diseases caused the most deaths, overt mistreatment by Europeans was equally devastating.

The history of Indigenous relations with Europeans in Canada since the 16th century can be described in four stages (Patterson, 1972). In the first stage, the relationship was largely mutually beneficial and profitable as the Europeans relied on Indigenousgroups for knowledge, food, and supplies, whereas the Indigenous people traded for the products of European technologies. In the second stage, however, Indigenous people were increasingly drawn into the European-centred economy, coming to rely on fur trading for their livelihood rather than their own Indigenous economic activity. This resulted in diminishing autonomy and increasing subjugation economically, militarily, politically, and religiously. In the third stage, the reserve system was established, clearing the way for full-scale European colonization, resource exploitation, agriculture, and settlement. If Indigenous people tried to retain their stewardship of the land, Europeans fought them off with superior weapons. A key element of this issue is the Indigenous view of land and land ownership. Most First Nations cultures considered the Earth a living entity whose resources they stewarded. The concepts of private land ownership and exploitation did not exist in Indigenous societies. The last stage of the relationship developed after World War II, when Indigenous Canadians began to mobilize politically to challenge the conditions of oppression and forced assimilation they had been subjected to. In this stage, Indigenous people developed political organizations and turned to the courts to fight for treaty rights and self-government.

A key turning point in Indigenous-European relations was the Royal Proclamation of 1763 which established British rule over the former French colonies, but also established that lands would be set aside for First Nations people. It legally established that First Nations had sovereign rights to their territory. Although these were often disputed, challenged, or ignored by the arriving waves of colonists, land speculators, and subsequent government administrations, they became the basis of contemporary treaty rights and negotiations.

The Indian Act of 1876 was another turning point. The Act attempted to codify and formalize the provisions of the Royal Proclamation and all other accumulated acts of government with respect to First Nations along the lines of a paternalistic “civilizing policy.” The care of the Indigenous population was placed under the control of the federal government until they were assimilated into European culture. In effect, discrimination against Indigenous Canadians was institutionalized in a series of provisions intended to subjugate them and keep them from gaining any power. The belief was that a separate act to govern Indigenous peoples would no longer be necessary once they had integrated into society. As the deputy superintendent of Indian Affairs said in 1920, “Our objective is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic and there is no Indian question, and no Indian Department” (as cited in Leslie, 1978). Nevertheless the Indian Act became the most pervasive mechanism in Indigenous life, regulating and controlling everything from who could be defined as an Indian, to the reserve and band council system, to the types of Indigenous activities that would no longer be permitted (e.g., potlatch and ceremonial dancing).

Some of the most impactful provisions of the Indian Act (and its subsequent amendments) were:

-

The prohibition against owning, acquiring, or “pre-empting” land

-

The dismantling of traditional institutions of Indigenous government and the banning of ceremonial practices

-

The imposition of the band council system, which was foreign to Indigenous tradition and powerless to make meaningful decisions without approval of the Department of Indian Affairs

-

Denial of the power to allocate funds and resources

-

The prohibition against hiring lawyers or seeking legal redress in pursuing land claims

-

The denial of the right to vote municipally (until 1948), provincially (until 1949), and federally (until 1960) (Mathias & Yabsley, 1991)

Indigenous Canadian culture was further eroded by the establishment of residential schools in the late 19th century, as described earlier in this chapter. These schools, run by both Christian missionaries and the Canadian government, also had the express purpose of “civilizing” Indigenous Canadian children and assimilating them into European society. The residential schools were located off-reserve to ensure that children were separated from their families and culture. Schools forced children to cut their hair, speak English or French, and practice Christianity. Education in the schools was substandard, and physical and sexual abuses were rampant for decades; only in 1996 did the last of the residential schools close. Prime Minister Stephen Harper delivered an apology on behalf of the Canadian government in 2008. Many of the problems that Indigenous Canadians face today result from almost a century of traumatizing mistreatment at these residential schools.

Current Status

The eradication of Indigenous Canadian culture continued until the 1960s, when First Nations began to mobilize politically and intensify their demands for Indigenous rights. The Liberal government’s White Paper of 1969 became a focus of Indigenous protest as it proposed to eliminate the Indian Act, the Department of Indian Affairs, and the concept of Indigenous rights altogether. First Nations people would be treated just like everyone else, as if the sovereign treaties and centuries of oppression had not occurred. Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau declared, “No society can be built on historical might-have-beens” (as cited in Weaver, 1981, p. 55). By the time of the repatriation of the Constitution in 1982, the government’s position had reversed and the status of Indians, Inuit, and Métis were recognized, as were existing Indigenous and treaty rights. The 1996 Nisga’a Treaty of the Nisga’a people of the Nass Valley in northern British Columbia is the first modern treaty in British Columbia. The comprehensive treaty provisions for the Nisga’a’s right to self-government and authority over lands and resources serve as a new model for First Nations–Crown relations in Canada.

However, First Nations people still suffer the effects of centuries of degradation. As noted earlier in the chapter, the income of Indigenous people in Canada is far lower than that of non-Indigenous people and rates of child poverty are much greater. Even though the last residential school closed in 1996, the problem of Indigenous education remains grave with 40% of all Indigenous people failing to complete high school. Long-term poverty, inadequate education, cultural dislocation, and high rates of unemployment contribute to Indigenous Canadian populations falling to the bottom of the economic spectrum. Indigenous Canadians also suffer disproportionately with poorer health outcomes and lower life expectancies than most groups in Canada.

The Québécois

Modern Canada was founded on the displacement of the Indigenous population by two colonizing nations: the French and the British. The French and the British were the two “charter groups” of Confederation and the British North America Act of 1867. The British North America Act (renamed the Constitution Act, 1867 in 1982) protected the linguistic, religious, and educational of the French and English in Quebec and Ontario, as well as the rest of the country. However, the French were both colonized by the English and, by 1867, were a numerically smaller group, leading to a relationship of inequality that has been a prominent issue throughout Canada’s history. Due to their linguistic and cultural isolation in English speaking North America, the Québécois —or “les habitants,” descendants of the original settlers from France — developed a unique ethnic identity, which became the basis of nationalist and sovereigntist aspirations during the Quiet Revolution of the 1960s.

How and Why They Came

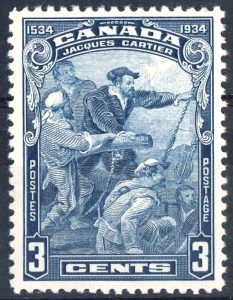

French colonists began to settle New France after Jacques Cartier’s exploration of the St. Lawrence River in 1534. Permanent French settlements were established in Port Royal, Acadia (now Nova Scotia) in 1605, and Quebec City in 1608. By the time of the British conquest of Acadia in 1710 and the defeat of Montcalm’s army in Quebec in 1760, there were approximately 60,000 French settlers. Most of the settlers could trace their origins to the northwest of France, particularly present-day Normandy. One estimate suggests that the Québécois descend from only 5,800 original immigrants from France who arrived between 1608 and 1760 (Marquis, 1923). The economy of New France was based on agriculture and the fur trade, but with the arrival of the British and especially the British Loyalists escaping the American Revolution in 1776, a pattern of British economic and financial domination emerged.

History of Intergroup Relations

The establishment of British rule in Canada was accomplished by conquest; that is, the forcible subjugation of territory and people by military action. Port Royal was ceded to the British in the Treaty of Utrecht of 1713, and Quebec and Montreal in the Treaty of Paris of 1763. As noted earlier, after attempts at assimilating the French population, the conquest of Port Royal and Acadia led eventually to the Great Expulsion of 1755, in which a large portion of the Acadian French population was deported from Nova Scotia. However, from the time of the Treaty of Paris onward, the British recognized the need to accommodate the French in Canada to avoid the problem of pacifying a large and hostile population. The Quebec Act of 1774 granted religious and linguistic rights to the French, and the Constitution Act of 1791 divided the province of Canada into Upper and Lower Canada, each with the power of self-government. The division of Canada into two founding charter groups — French and English — was further established by Confederation. The British North America Act (Constitution Act) of 1867 protected the religious, educational, and linguistic rights of the French and English in Canada. In addition, civil law in Quebec continued to be based on the French Napoleonic Code of 1804: the Civil Code of Lower Canada (1866).

Despite the notion that the two-founding-nations of Canadian Confederation were equal, English-speaking Canadians in Montreal held the positions of power in the economy. English was the language of commerce in Quebec. The French-speaking population in Quebec were largely rural, agricultural, and dominated by the Catholic Church until the mid-20th century. Although the Québécois achieved status as a new middle class of lawyers, doctors, administrators, politicians, scientists, and intellectuals, they were effectively barred from the upper echelons of the class system. English and French tended to live in what Canadian author Hugh MacLennan famously called “two solitudes.” This ethnic stratification system began to be challenged during the period of the Quiet Revolution in Quebec in the 1960s when the control of the Catholic Church was challenged in the spheres of education, health, and welfare, and the long-standing politically reactionary Union Nationale government of Maurice Duplessis was defeated by Jean Lesage’s Liberals. In the process of modernizing the state to address the new conditions of industrialization, urbanization, and continental capitalism, the Quebec independence movement emerged alongside an increasingly militant labour movement.

To address the emerging crisis of Canadian unity, the federal government appointed the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism in 1963. True to its name, the commission tried to address the grievances of the Québécois solely as cultural and linguistic matters. The report of the commission emphasized ways in which the equality of the two founding peoples could be recognized and led to the Official Languages Act of 1969. The Act recognized French and English as the two official languages in Canada and mandated that federal government services and the judicial system would be conducted in both languages. However, when a small terrorist group — the Front de Libération du Québec (FLQ) — kidnapped a provincial government minister and a British diplomat in 1970, the response of the federal government was to implement the War Measures Act, suspending the rights of Canadians from coast to coast and arresting and detaining hundreds of individuals without legal due process. The notion of equal partnership between French and English Canada was proven to be questionable at best.

In 1976, the Parti Québécois was elected as an explicitly separatist political party. It failed to get sufficient votes to separate from Canada in the provincial referendum on sovereignty in 1980, but the move to repatriate the constitution from Great Britain without the consent of Quebec in 1982 fueled nationalist sentiment. Subsequent attempts to include Quebec as a voluntary signatory to the Constitution failed in 1987 (the Meech Lake Accord) and 1992 (the Charlottetown Accord). Many people in Quebec regarded these failures as rejection of Quebec by the English majority in other parts of the country. In 1995 a second referendum on Quebec sovereignty was a narrowly defeated by a vote of 50.5% to 49.5%. The history of intergroup relations between the French and English in Canada on the model of equal partnership has therefore proven to be a tenuous experiment in dual nationhood.

Current Status

A major component of the grievances between the French and English in Canada has been the social inequality of the French and English and the threat to Québécois linguistic and cultural survival. Income data from 1991 prior to the second referendum indicated that the income disparity between French and English Canadians both within and outside the province of Quebec had more or less disappeared, suggesting that the issues of intergroup relations had shifted to political, linguistic, and cultural alienation in Canada (Li, 1996).

Bill 101 or the Charter of the French Language was passed in 1977 in Quebec to protect the French language in Quebec. It defines French as the official language of Quebec, limits the use of English in commercial signs, and restricts who may enroll in English schools. Although it remains controversial, it appears to have been effective in preserving the French language. Linguistically, there were 8.1 million people who reported speaking French at home in 2016 compared to 7.9 million in 2006, although this represented a decline from 23.8% to 23.4% of the total population of Canada. (This is much lower than the 28 to 30% of population who claimed French origin in the first half of the 20th century, however). In Quebec, 75.1% of the population spoke only French at home in 2006 compared to 71.2% in 2016. This decline was paralleled by the decline in the proportion of the population who spoke only English at home in the rest of Canada from 77.1% to 72.2% between 2006 and 2016 (due to immigration). On the other hand, the number of people reporting that they were able to conduct conversation in both French and English increased by 420,495 to 6.2 million people between 2011 and 2016. Bilingualism was reported by 17.9% of the population, albeit largely in Quebec. In Quebec, 44.5% of people reported being able to conduct conversation in both English and French (Statistics Canada, 2012; Statistics Canada, 2017a; Statistics Canada, 2017b).

Black Canadians

As discussed in the section on race, the term “Black Canadian” is usually preferred to the term African Canadian. Many people with dark skin in Canada have roots in the Caribbean rather than being descendants of the African slaves from the United States. They see themselves ethnically as Caribbean Canadians. Further, actual immigrants from Africa may feel that they have more of a claim to the term “African Canadian” than those who are many generations removed from ancestors who originally came to this country. The commonality of Black Canadians is more a function of racism rather than origin.

How and Why They Came

The first Black Canadians were slaves brought to Canada by the French in the 17th century. It is reported that at least 6 of the 16 legislators in English Upper Canada also owned slaves (Mosher, 1998). The economic conditions in Canada were not conducive to slavery so the practice was not widespread. Nevertheless, it was not until 1834 that slavery was banned throughout the British Empire, including Canada. Canada became the terminus of the famous Underground Railroad, a secret network organized by American abolitionists to transport escaped slaves to freedom. Between the American Revolution in 1776 and the end of the American Civil War in 1865, Canada received approximately 60,000 runaway slaves and Black Empire Loyalists from the United States. It is estimated that 10% of the Empire Loyalists who came to Canada following the American Revolution were Black (Walker, 1980). Many Black Canadians returned to the United States after the Civil War, and by 1911 there were only about 17,000 left in Canada (Mosher, 1998).

After the change in immigration policy in the late 1960s, Blacks from the Caribbean and elsewhere began to immigrate to Canada in increasing numbers. Prior to 1971, Canadians of Black origin made up less than 1% of the population (Li, 1996). In the 2016 census, they made up 3.5% of the population and 15.6% of all visible minorities in the country. The Black population is highly urbanized, with 94.3% of Blacks lived in cities (compared to 71.2% of the whole population): 36.9% of Blacks lived in Toronto (down from 46.9% in 2001) and 22.6% in Montreal (making them the largest visible minority group in Montreal) (Statistics Canada, 2019a; 2019b). However Ottawa-Gatineau, Lethbridge and Moncton had the fastest growing Black populations between 1996 and 2016. It is interesting to note that among those who self-identified as Black in the 2016 census, 12% reported being both “White” and “Black.”

Blacks with origins in the Caribbean make up the largest proportion of Black Canadians with nearly 40% having Jamaican heritage and an additional 32% having heritage elsewhere in the Caribbean (Statistics Canada, 2007). Many Caribbean people come to Canada as part of the Canadian Seasonal Agricultural Workers Program or as domestic workers with temporary work permits, although the permanent Caribbean community in Canada has more or less the same higher education attainments and full-time employment rates as the rest of the population. Over time, the source of Black immigrants to Canada has shifted from the Caribbean to Africa. Before 1981 83.3% of Black immigrants were from the Caribbean, whereas 4.8% were from Africa. In 2016, 27.3% were from the Caribbean, whereas 65.1% were from Africa (Statistics Canada, 2019b). In particular, there has been an increase in immigration of Somalis from Africa as people fled conflict in the area. In the 2011 census, 4.4% of the Black population in Canada claimed Somali origin (Statistics Canada, 2013). Between 1988 and 1996, more than 55,000 Somali refugees arrived in Canada, representing the largest Black immigrant group ever to come to Canada in such a short time (Abdulle, 1999).

History of Intergroup Relations

Although slavery became in illegal in Canada in 1834, Blacks did not effectively enjoy equal rights in Canada. Blacks had the same legal status as Whites in Canada, but strongly held prejudices and informal practices of segregation lead to pervasive discrimination against the escaping slaves and Black Empire Loyalists in the 19th century. Blacks could vote and sit on juries, but these rights were frequently challenged by White citizens. As noted earlier in this chapter, Ontario (outside of Toronto) and Nova Scotia enacted laws to segregate schools along racial lines that remained in effect until 1965 in Ontario and 1983 in Nova Scotia (Black History Canada, 2014).

Blacks were also segregated into residential neighbourhoods in Toronto, Hamilton, and Windsor (Mosher 1998). In Halifax, the community of Africville was set aside for Blacks as early as 1749, although most accounts place its establishment to the arrival of Black Loyalists after the War of 1812. It was considered a slum by city councillors and was bulldozed between 1965 and 1970 without meaningful consultation with its residents.

Blacks were also restricted by the type of occupations they could pursue. The employment of Blacks through the first half of the 20th century was typically limited to being domestic workers or railroad porters. For example, the father of Oscar Peterson, the famous jazz pianist, was a Canadian Pacific railroad porter in Montreal, while his mother was employed as a domestic worker (Library and Archives Canada, 2001). Otherwise, for most of the 20th century, Black Canadians were mostly employed in low-pay service jobs or as unskilled labour.

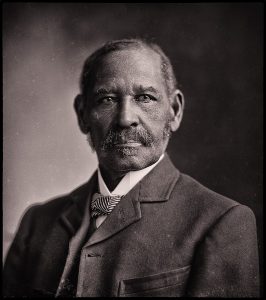

The story of a large group of Black immigrants who arrived in Victoria, British Columbia, from San Francisco in the 1850s, illustrates some of the ambiguities of the early Black experience in Canada. The Blacks were initially welcomed to the British colony by Governor Douglas, who assured them they would have full civic rights. Douglas and others were worried that the immigration of White Americans to Vancouver Island might lead to annexation by the United States and the arrival of several hundred Black immigrants would help to prevent that eventuality. There was also need for an industrious and reliable workforce and by 1858 the Black immigrants were fully employed. In 1859, an all-Black Victoria Pioneer Rifle Company was formed to fight in the “Pig War” dispute with the United States over the San Juan Islands. The de facto leader of the Black immigrant group, Mifflin Gibbs (1823-1915), was a successful shopkeeper and prominent member of the community. He won a seat on city council in the wealthiest ward of the city, James Bay, and acted as temporary mayor for a time. He was also the Salt Spring Island representative to the Yale Convention where British Columbia’s terms for joining Confederation were drawn up.

On the other hand, tensions and discrimination began to develop between the Black and White communities. Schools were integrated and only one church was segregated. However a dispute over Black voting led to a racist campaign by future premier Amor de Cosmos. Blacks began to be denied access to some saloons and desired seating in theatres. An incident in 1860 involving a brawl that began when two Blacks were denied their legitimate entry into Victoria’s Colonial Theatre generated newspaper accounts that blamed the Blacks for causing trouble. As influential as Gibbs was, he was denied tickets to the retirement banquet of Governor Douglas, who had originally been a great supporter of the Black immigrants. By the time Gibbs returned to the United States in 1870, the end of slavery after the U.S. Civil War had already led to many of the Black community leaving Victoria. Without Gibbs’s presence, the Black community declined even further and eventually disappeared (Ruttan, 2014).

Current Status

Although formalized discrimination against Black Canadians has been outlawed, in many respects equity does not yet exist. The 2016 census shows that Black males earned 66 cents for every dollar a White male worker earned in Canada, or $19,103 less on average per year. Black females earned 83 cents for every dollar a White female worker earned in Canada, or $6347 less on average per year. In 2016, 23.9% of Blacks lived in poverty (compared to 12.2% of non-racialized individuals) (Block, Galabuzi & Tranjan, 2019). In addition Blacks are subject to greater degrees of racial profiling than other groups. Racial profiling refers to the practice of selecting specific racial groups for greater levels of criminal justice surveillance. Despite police denials, Wortley and Tanner’s study confirms Black complaints in Toronto that they are more frequently stopped, questioned, and searched by the police for “driving while being Black” violations than other groups (2004).

Asian Canadians

Like many groups this section discusses, Asian Canadians represent a great diversity of cultures and backgrounds. The national and ethnic diversity of Asian Canadian immigration history is reflected in the variety of their experiences in joining Canadian society. Asian immigrants have come to Canada in waves, at different times, and for different reasons. The experience of a Japanese Canadian whose family has been in Canada for five generations will be drastically different from a Laotian Canadian who has only been in Canada for a few years. This section primarily discusses the experience of Chinese, Japanese, and South Asian immigrants.

How and Why They Came

The first Asian immigrants to come to Canada in the mid-19th century were Chinese. These immigrants were primarily men whose intention was to work for several years in order to earn incomes to support their families in China. Their first destination was the Fraser Canyon for the gold rush in 1858. Many of these Chinese came north from California. By 1860, British Columbia had an estimated population of 7,000 Chinese (out of a total population of approximately 51,000). The second major wave of Chinese immigration arrived in the 1880s for the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway when contractors recruited thousands of workers from Taiwan and Guangdong Province in China. Chinese labourers were paid approximately a third of what White, Black, and Indigenous workers were paid. Even so, they were used to complete the most difficult sections of track through the rugged Fraser Valley Canyon, living under squalid and dangerous conditions; 600 Chinese workers died during the construction of the rail line. Chinese men also engaged in other manual labour like mining, laundry, cooking, canning, and agricultural work. The work was gruelling and underpaid, but like many pioneering immigrants they persevered (Chan, 2013).

Japanese immigration began in 1887 with the arrival of the first Japanese settler, Manzo Nagano. The Issei (first wave of Japanese immigrants) were, like the first Chinese immigrants, mostly men. They came from fishing and farming backgrounds in the southern Japanese islands of Kyushu and Honshu. They settled in Japantowns in Victoria and Vancouver, as well as in the Fraser Valley and small towns along the Pacific coast where they worked mostly in fishing, farming, and logging. Like the Chinese settlers, they were paid much less than workers from European backgrounds and were usually hired for menial labour or heavy agricultural work. With restrictions imposed on the immigration of Japanese men after 1907, most of the early Japanese immigrants after 1907 were women, either the wives of Japanese immigrants or women betrothed to be married. By 1914, there were about 10,000 Japanese in Canada (Sunahara & Oikawa, 2011).

South Asians refer to a diverse group of people with different ethnic backgrounds in India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka. The first South Asians in Canada were Sikhs whose origins were in the Punjab region of India. The first group of Sikhs arrived in Vancouver in 1904 from Hong Kong, attracted by stories of high wages from British Indian troops who had traveled through Canada the previous year (Buchignani, 2010). They were encouraged by Hong Kong–based agents of the Canadian Pacific Railway who had seen travel on their passenger liners plummet with the head tax imposed on Chinese immigration. Most of the first Sikhs in Canada arrived via Hong Kong or Malaysia, where the British had typically employed them as policemen, watchmen, and caretakers. They were originally from rural areas of Punjab and mortgaged their properties for passage with the prospect of sending money home. Many arrived in Canada unable to speak English but eventually found employment in mills, factories, the railway, and Okanagan orchards (Johnston, 1989). By 1908 there were over 5,000 South Asians in British Columbia, 90% of them Sikh. Many of them settled in Abbotsford (Buchignani, 2010).

History of Intergroup Relations

Asian Canadians were subject to particularly harsh racism in British Columbia and elsewhere in Canada in the 19th and 20th centuries. Based on orientalist stereotypes, they were not considered “suitable” for Canadian citizenship. The 1902 Royal Commission on Chinese and Japanese Immigration declared that the Japanese and Chinese were “unfit for full citizenship. They are so nearly allied to a servile class that they are obnoxious to a free community and dangerous to the state” (CBC, 2001). The right of Asians to vote, own property, and seek employment, as well as their ability to immigrate and integrate into Canadian society were therefore severely restricted. The right to vote federally and provincially was denied to Chinese Canadians in 1874, Japanese Canadians in 1895, and South Asians in 1907. This disenfranchisement also prevented these groups from having access to political office, jury duty, professions like law, civil service jobs, underground mining jobs, and labour on public works because these all required being on provincial voters lists. Voting rights were only returned to Chinese and South Asian Canadians in 1947 and to Japanese Canadians in 1949, whereas immigration restrictions were not removed until the 1960s.

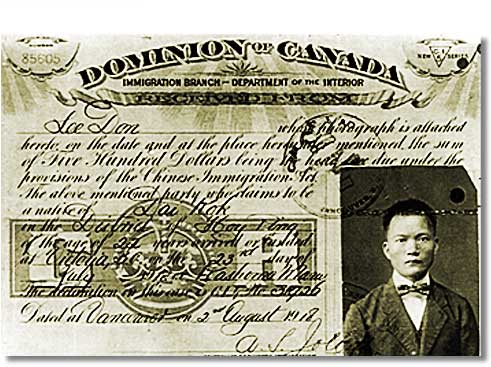

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the immigration of Chinese workers to Canada, especially during the final stages of the building of Canadian Pacific Railway, led to increasing numbers of single Chinese men in the country who sought to bring their wives to join them. After the railway was completed, the imposition of “head taxes” of $50 in 1885 and $500 in 1903 were attempts to restrict Chinese immigration. As the Chinese workers were typically paid much lower wages than workers of European origin, various Asian exclusion leagues developed to press for further restrictions on Asian immigration. This led to riots in Vancouver in 1907 and eventually in 1923 to a complete ban on Chinese immigration.

For similar reasons, the immigration of Japanese men was restricted to 400 a year after 1907, and further reduced to 150 individuals a year after 1928. Their success in the fishing industry led the federal fisheries department to arbitrarily reduce Japanese trolling licences by one-third in 1922. They, like the Chinese, were also subject to “yellow peril” hysteria. When the Japanese, many veterans of the Russo-Japanese war of 1905, successfully defended their community against White supremacist mobs in the 1907 anti-Asian riots in Vancouver, they were accused of smuggling a secret army into Canada (Sunahara & Oikawa, 2011). An even uglier action was the establishment of Japanese internment camps of World War II, discussed earlier as an illustration of expulsion.

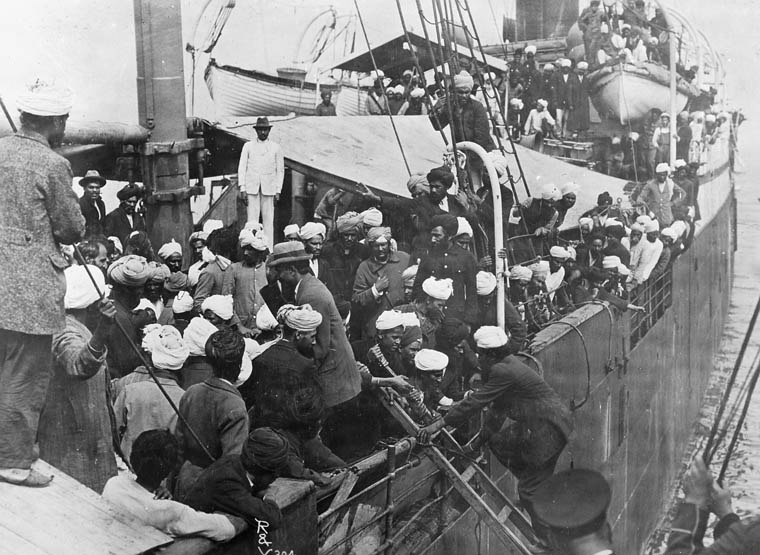

Of the three groups, South Asians were the most recent to arrive. However, by 1908 the large number of arrivals also led to the imposition of immigration restrictions. As the South Asians were British subjects, the restrictions took a more devious form, however. Immigrants from South Asia were obliged to possess at least $200 on arrival (very challenging considering that in British India they might be able to earn 10 to 20 cents a day), and they had to arrive in Canada by continuous passage from India. The government then put pressure on steamship companies not to sell direct through-passage tickets from Indian ports. The famous incident of the freighter Komagata Maru in 1914 was a direct consequence of this restriction. The ship, carrying 376 South Asian immigrants, many of whom had boarded in Hong Kong, was prevented from docking and kept in isolation in Vancouver harbour for two months until forced to return to Asia. Only 20 of the 376 passengers were allowed to stay in Canada (Johnston, 1989).

Current Status

Asian Canadians certainly have been subject to their share of racial prejudice, despite their seemingly positive stereotype today as the model minority. The model minority stereotype is applied to a minority group that is seen as reaching significant educational, professional, and socioeconomic levels without challenging the existing establishment. In the 2006 census, those identifying as Japanese earned 120% of the income of White Canadians, Chinese 88.6%, and South Asians 83.3% (Block & Galabuzi, 2011).

This stereotype is typically applied to Asian groups in Canada, and it can result in unrealistic expectations, putting a stigma on members of this group that do not meet the expectations. Stereotyping all Asians as smart, industrious, and capable can also lead to a lack of much-needed government assistance and to educational and professional discrimination. Some critics speak of a “bamboo ceiling” when it comes to Asians reaching the highest echelons of corporate success. It has been difficult for Asian Canadians to overcome the stereotypes that they are passive, lack communication skills, are “techies,” or not “real” Canadians.

The COVID-19 pandemic that began in 2020 has also been an event of renewed racism and xenophobia directed towards the Chinese and Asian community. Because of early reports that the pandemic began in a “wet market” in Wuhan, China, where wild animals were sold, the Chinese community has been blamed for the pandemic. US President Donald Trump referred to COVID-19 as the “Chinese virus,” for example, and many of the old “yellow peril” narratives have been revived. “Asians continue to be viewed as foreigners whose cultural values and practices are not only incompatible with the North American way of life, but also threats to the health and well-being of Canadian people” (Lou et al., 2021). Lou et al.’s (2021) survey of 874 Chinese Canadians, revealed that between 57% and 61% of respondents reported being treated with disrespect due to their ethnic background and between 35% and 40% reported being personally threatened or intimidated. Hate crimes against Chinese Canadians reported to the Vancouver police department increased by 717% in 2020 compared to 2019. As one of the survey participants described:

Walking on the streets and getting called an idiot by a lady. Hostile stares when walking on the streets, even with a mask on. Discriminatory remarks at work (e.g., during a PPE training, the instructor tells me to re-tie my ponytail into a bun to put a cap on, but adds “that’s how Chinese girls spread the virus”).

The COVID-19 pandemic has therefore been described as a dual pandemic: one based on the virus, which already disproportionately affects ethnic minorities’ health and employment, the other based on racism.

Media Attributions

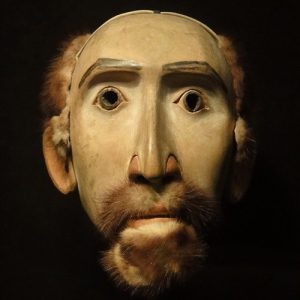

- Figure 11.22 First Nations CEF Soldiers by Canada. Dept. of the Interior from Library and Archives Canada /PA-041366/ MIKAN ID number 3192219, via Wikimedia Commons, is in the public domain.

- Figure 11.23 “White man mask by BC coastal natives in 1700s – at the BC Royal Museum in Victoria” by John Koetsier (Username: johnkoetsier), via Flickr, is used under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 licence.

- Figure 11.24 Jacques Cartier 1934 issue-3c by George Arthur Gundersen (1910-1975) [Picture engraved by Bruce Hay], via Wikimedia Commons, is in the public domain. [Copyright on the engraving owned by the British American Bank Note Company]

- Figure 11.25 St-Jean!042 by Francistremblay 18, via Wikimedia Commons is released into the public domain.

- Figure 11.26 Sleeping car porter in 1950s from the Canadian Railroad Historical Association (CRHA) Archives and Documentation Centre /Exporail, Canadian Pacific Railway Company Fonds is used with permission.

- Figure 11.27 Mifflin Wistar Gibbs by Charles Milton Bell Studios, C.M. Bell Studio Collection from Library of Congress /LC-DIG-bellcm-12837 (digital file from original), via Wikimedia Commons, is in the public domain.

- Figure 11.28 Chinese Head Tax Receipt by unknown source, via Wikimedia Commons, is in the public domain.

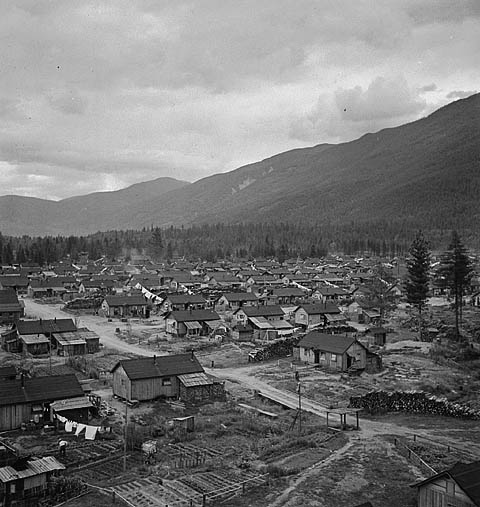

- Figure 11.29 Japanese internment camp in British Columbia, by Jack Long from Library and Archives Canada, reproduction number PA-142853 and MIKAN ID number 3623175, via Wikimedia commons, is in the public domain.

- Figure 11.30 Komogata Maru LAC a034014 1914 by from Library and Archives Canada, PA-034014, via Wikimedia Commons, is in the public domain.

- Figure 11.31 Dots by Susan Jane Golding, via OpenVerse, is used under a CC BY 2.0 licence.