17.3 The De-Centring of the State: Terrorism, War, Empire, and Political Exceptionalism

In Dawn of the Planet of the Apes (2014), the post-apocalyptic narrative of brewing conflict between the apes — descendants of animal experimentation and genetic manipulation — and the remaining humans — survivors of a human-made ape virus pandemic — follows a familiar political story line of mistrust, enmity, and provocation between opposed camps during a time of crisis. The film may be seen as a science fiction allegory of any number of contemporary cycles of violence, including the 2014 Israeli-Palestinian conflict, which was concurrent with the film’s release. In the first part of the movie, the two communities co-exist in a kind of pre-political state, struggling in isolation from one another in an effort to survive. There is no real internal conflict or disagreement within them that would have to be settled politically. The communities have leaders, but leaders who are listened to only because of the respect accorded to them. However, when the two communities come into contact unexpectedly, a political dynamic begins to emerge in which the question becomes whether the two groups will be able to live in peace together or whether their history and memory of hatred and disrespect will lead them to conflict. It is a story which asks whether it is going to be the regulative moral codes that govern everyday social behaviour or the friend/enemy dynamics of politics and war that will win the day. The underlying theme is that when the normal rules that govern everyday behaviour are deemed no longer sufficient to conduct life, politics as an exception in its various forms emerges.

The concept of politics as exception has its roots in the origins of sovereignty (Agamben, 1998). It was articulated most clearly in the 1920s in the work of Carl Schmitt (1922) who later became juridical theorist aligned with the German Nazi regime in the 1930s. Schmitt argued that the authentic activity of politics — the sphere of “the political” — only becomes clear in moments of crisis when leaders are obliged to make a truly political decision, (for example, to go to war). This occurs when the normal rules that govern decision making, or the application of law appear to be no longer adequate or applicable to the situation confronting society. Specifically, a state of exception exists when the law or the constitution is temporarily suspended during a time of crisis so that the executive leader can claim emergency powers. Schmitt eventually applied this principle to justify the German National Socialist Party’s suspension of the Weimar constitution in 1933, as well as the Führerprinzip (principle of absolute leadership) that characterized the dictatorship of Adolf Hitler. Nevertheless, political exceptionalism is a reoccurring theme in politics and as situations of crisis have become increasingly normal in recent decades — the war on terror, failed states, the erosion of sovereign power under globalism, pandemics, climate change, etc. — it becomes necessary for sociologists to examine the role of politics under conditions of social crisis.

A subplot in Dawn of the Planet of the Apes involves the relationship between the leader of the apes, Caesar, and Koba, whose life as a victim of medical experimentation leads him to hate humans and challenge Caesar’s attempts to find reconciliation with them. Until the moment of contact, the apes are able govern themselves by a moral code and mutual agreement on decisions. It is an ideal, peaceful pre-political society. One central rule of the apes’ moral identity was that “ape does not kill ape,” unlike the humans whose society disintegrated into violent conflict following the global pandemic. However, when Koba’s betrayal of Caesar leads to a war with the humans that threatens the apes’ survival, Caesar is forced to make an impossible decision: break the moral code and kill Koba, or risk further betrayal and dissension that will undermine his ability to lead. Caesar’s solution is to kill Koba but only after making a crucial declaration that keeps the apes’ moral code intact: “Koba not ape!” He essentially declares that Koba’s transgression of the apes’ way of life was so egregious that he could no longer be considered an ape and therefore he can be killed. Koba was declared to be an Other, outside the protection of the law.

This is an example of political exceptionalism. In this case, Caesar suspends the law of the apes and dispenses with Koba in his first act of emergency power. Caesar decides who is and who is not an ape, and who is and who is not protected by ape law. The law is preserved, but it is revealed to be radically fluid and dependent on Caesar’s decision.

This possibility of the state of exception is built into the structure of the modern state. The modern state system, based on the concept of state sovereignty, came into existence after the Thirty Years War in Europe (1618–1648) as a solution to the problem of continual, generalized states of war. The principle of state sovereignty is that within states, peace is maintained by a single rule of law, while war (i.e., the absence of law) is expelled to the margins of society as a last resort in times of exception. The concept of “society” itself, as a peaceable space of normative interaction, depends on this expulsion of violent conflict to the borders of society (Walker, 1993). When society is threatened however, from without or within, the conditions of a temporary state of exception emerge. Constitutional governments often provide a formal mechanism for declaring a state of exception or emergency powers, like the Canadian Emergencies Act. Many observers of contemporary global conflict have noted, however, that what were once temporary states of exception — wars between states, wars within states, wars by non-state actors, and wars or crises resulting in the suspension of laws — have become increasingly permanent and normalized in recent years. The exception is increasingly becoming the norm (Agamben 2005; Hardt and Negri, 2004).

Several phenomena of current political life allow sociologists to examine political exceptionalism: global terrorism, the contemporary nature of war, the re-emergence of Empire, and the routine use of states of exception.

Terrorism: War by Non-State Actors

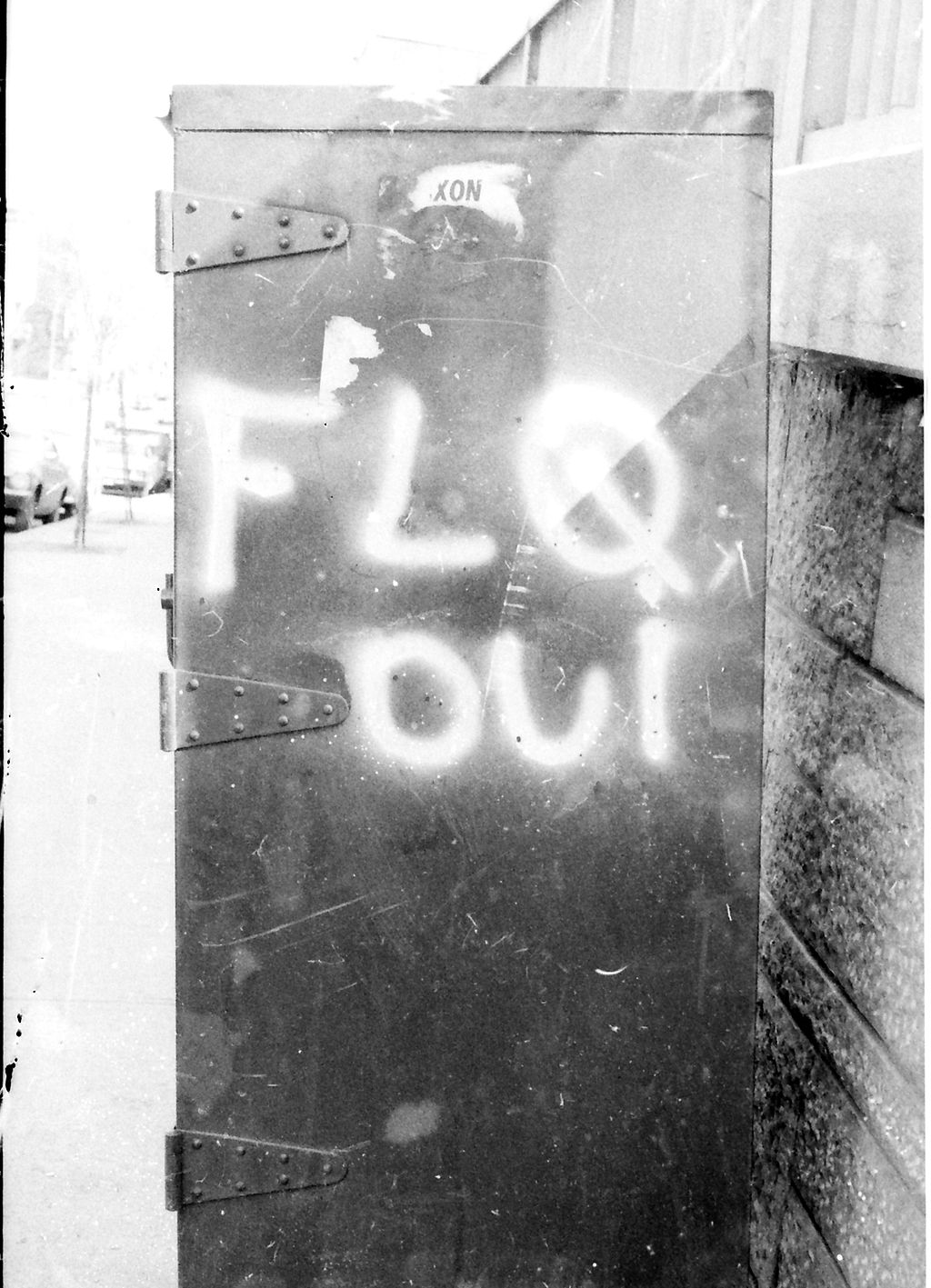

Since 9/11, the role of terrorism in restructuring national and international politics has become apparent. As defined earlier, terrorism is the use of violence on civilian populations and institutions to achieve political ends. Typically, this violence is a product of non-state actors seeking radical political change by resorting to means outside the normal political process. They unilaterally suspend the law when they challenge the state’s legitimate monopoly over the use of force in a territory. Al-Qaeda for example is an international organization that had its origin in American-funded efforts to organize an insurgency campaign against the Russian occupation of Afghanistan in the 1980s. Its attacks on civilian and military targets, including the American embassies in East Africa in 1998, the World Trade Center in 2001, and the bombings in Bali in 2002, are means to demand the end of Western influence in the Middle East and the establishment of fundamentalist Wahhabi Islamic caliphates. On a much smaller scale, in the 1960s the FLQ (Front de libération du Québec) resorted to bombing mailboxes, the Montreal Stock Exchange, and kidnapping political figures to press for the independence of Quebec.

Terrorism is an ambiguous term, however, because the definition of who or what constitutes a terrorist differs depending on who does the defining. There are three distinct phenomena that are defined as terrorism in contemporary usage: (a) the use of political violence as a means of political action by non-state actors against a legitimate government, (b) the use of political violence by governments themselves in contravention of national or international codes of human rights, and (c) the use of violence in war that contravenes established rules of engagement, including violence against civilian or non-military targets, i.e., war crimes (Hardt and Negri, 2004). Noam Chomsky argues, for example, that the United States government is the most significant terrorist organization in the world because of its support for illegal and irregular wars, its backing of authoritarian regimes that use illegitimate violence against their populations, and its history of destabilizing foreign governments and assassinating foreign political leaders (Chomsky, 2001; Chomsky and Herman, 1979).

War: Politics by Other Means

Even before there were modern nation-states, political conflicts arose among competing societies or factions of people. Vikings attacked continental European tribes in search of loot, and later, European explorers landed on foreign shores to claim the resources of Indigenous peoples. Conflicts also arose among competing groups within individual sovereign territories, as evidenced by the bloody English and American civil wars and the Riel Rebellion in Canada. Nearly all conflicts in the past and present, however, are spurred by basic desires: the drive to protect or gain territory and wealth, and the need to preserve liberty and autonomy. They are driven by an inside/outside dynamic that provides the underlying political content of war. War is defined as a form of organized group violence between politically distinct groups. Like the other forms of political exception, it involves the suspension of peacetime law and the implementation of emergency measures. As the 19th century military strategist Carl von Clausewitz (1832) said, war is the continuation of politics by other means.

In the 20th century, nine million people were killed in World War I and another 61 million people were killed in World War II. The death tolls in these wars were of such magnitude that the wars were considered at the time to be unprecedented. World War I, or “the Great War,” was described as the war that would end all wars, yet the manner in which it was settled led directly to the conditions responsible for the declaration of World War II. In fact, the wars were not unprecedented. Since the establishment of the modern centralized state system in Europe, there have been six European wars involving alliances between multiple nation-states at approximately half-century intervals. Prior to World War I and World War II, there was the Thirty Years War (1618–1648), the War of Spanish Succession (1702–1713), the Seven Years War (1756–1763), and the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars (1792–1815) (Dyer, 2014). The difference in the two 20th century world wars is that advances in military technology and the strategy of total war (involving the targeting of civilian as well as military targets) led to a massive increase in casualties. The total dead in 20th century wars is estimated at 111 million, approximately two-thirds of the 175 million people killed in total in war in the thousand years between 1000 and 2000 CE (Tepperman, 2010).

War is typically understood as armed conflict that has been openly declared between or within states. However recent warfare, like Canada’s involvement in the NATO mission in Afghanistan (from 2001 to 2014), more typically takes the form of asymmetrical conflict between professional state armies and insurgent groups who rely on guerilla tactics (Hardt and Negri, 2004). Asymmetrical warfare is defined by the lack of symmetry between the sides of a violent military conflict. There is a significant imbalance of technical and military means between combatants, which has been referred to by American military strategists as full spectrum dominance. This shifts the nature of the conflict to insurgency and counter-insurgency tactics in which the dominant, professional armies aim their efforts of deterrence against both the military operations of their opponents and the potentially militarized population. Counter-insurgency strategies seek not only to defeat the enemy army militarily but to control it with social, political, ideological, and psychological weapons. The Canadian army’s “model village” clear, hold, and build strategy in Afghanistan is an example of this, combining conventional military action with humanitarian aid and social and infrastructure investment (Galloway, 2009). On the other side, the insurgent armies compensate for their military weakness with the unpredictable tactics of guerilla war in which maximum damage can be done with a minimum of weaponry (Hardt and Negri, 2004).

One of the outcomes of contemporary warfare has been the creation of a condition of global post-security in which, as Hardt and Negri put it, “lethal violence is present as a constant potentiality, ready always and everywhere to erupt” (Hardt and Negri, 2004). Partly as a reaction to this phenomenon and partly as a cause, sociologists can speak of the development of war systems, or the normalization of militarization. This is “the contradictory and tense social process in which civil society organizes itself for the production of violence” (Geyer, 1989). This process involves an intensification of the conceptual division between the outsides and insides of nation-states, the demonization of enemies who threaten “us” from the outside (or the inside), the normalization of military ways of thinking and military perspectives on policy, and the propagation of ideologies that romanticize, sanitize, and validate military violence as a solution to problems or as a way of life (Graham, 2011). As commentators have noted, Canada’s relationship to military action has shifted during the Afghan operation from its Lester Pearson era of peacekeeping to a more militant stance in line with the normalization of militarization (Dyer, 2014).

Empire

The breakdown of states due to warfare or internal civil conflict is one way in which the sovereign nation-state is undermined in times of exception. Another way in which the sovereignty of the state and rule of law has been undermined is through the creation of supra-state forces like global capitalism and international trade agreements that reduce or constrain the decision-making abilities of national governments. When these supranational forces become organized on a formal basis, sociologists can begin to speak about the re-emergence of empires as a type of political exception.

Empires have existed throughout human history, but arguably there is something unique about the formation of the contemporary global Empire. In general, an empire (1) refers to a geographically widespread organization of individual states, nations, and people that is ruled by a centralized government, like the Roman Empire of antiquity or the Austro-Hungarian Empire until WWI. However, some argue that the formation of a contemporary global order has seen the development of a new unbounded and centre-less type of empire. Empire (2) today refers to a supra‐national, global form of sovereignty whose territory is the entire globe and whose organization forms around the nodes of a network form of power (on networks, see Chapter 7. Groups and Organizations). These nodes include the dominant nation‐states, supranational institutions (the UN, IMF, GATT, WHO, G7, etc.), major capitalist corporations, and international Non-Governmental Organizations or NGOs (Medecins San Frontieres, Amnesty International, CUSO, Oxfam, etc.) (Hardt and Negri, 2000).

As a result of the formation of this type of global empire, war, for example, is increasingly not fought between independent sovereign nation-states but as a kind of global-scale police action in which several states — or “coalitions of the willing” — intervene on humanitarian or security grounds to suppress dissent or conflict in different parts of the globe. Key to this shift in the nature of the use of force is the way in which military action, traditionally understood as armed combat between sovereign states, is reconceptualized as police action, traditionally understood as the legitimate use of force within a sovereign state. As the borders between states erode, the entire globe is redefined as a single, vast, internal sovereign state to be managed and governed as a domestic problem.

Normalization of Exception

As noted above, a state of exception refers to a situation when the law or the constitution is temporarily suspended during a time of crisis so that the executive leader can claim emergency powers. During warfare for example, it is typical for governments to temporarily suspend the normal rule of law and institute martial law. However, when times of crisis become the norm, this modality of power is resorted to more frequently and more permanently both on a large scale and small scale. Perhaps the most famous example of normalized political exceptionalism was the suspension of the Weimar Constitution by the Nazis in Germany between 1933 and 1945. On the basis of Hitler’s Decree for the Protection of the People and the State, the personal liberties of Germans were “legally” suspended, making the concentration camps for political opponents, the confiscation of property, and the Holocaust, in some sense, lawful actions. Under Alfredo Stroessner’s regime in Paraguay in the 1960s and 1970s, this form of legal illegality was taken to the extreme. Citing the state of emergency created by the global Cold War struggle between communism and democracy, Stroessner suspended Paraguay’s constitutional protection of rights and freedoms permanently except for one day every four years when elections were held (Zizek 2002).

On a smaller scale, albeit with global implications, U.S. President George Bush’s 2001 military order that authorized the trial by military tribunal and indefinite detention of “unlawful combatants” and individuals suspected of being involved in terrorist activities enabled a similar suspension of constitutional and international laws. The U.S. detention centre at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, where individuals were tortured and held without trial or due process, is a legally authorized space that is nevertheless outside of the jurisdiction and protection of the law (Agamben 2005).

Canada’s most famous incident of peacetime state of exception was Pierre Trudeau’s use of the War Measures Act in 1970 during the October Crisis. The War Measures Act was used to suspend civil liberties and mobilize the military in response to a state of “apprehended insurrection” following the FLQ’s kidnapping of Quebec politician Pierre Laporte and British diplomat James Cross. During the period of the War Measures Act, 3,000 homes were searched, and 497 individuals were arrested without due process, including several people in Vancouver who were found distributing the FLQ’s manifesto. Only sixty-two people were ever charged with offences, and the FLQ cells responsible for the kidnappings did not number more than a handful of individuals (Clément 2008). Although this incident is the most famous example of political exceptionalism in Canada, there are a number of pieces of legislation and processes that involve the mechanism of localized suspension of the law, notably the use of Ministerial Security Certificates under the 2001 Anti-Terrorism Act, which enables the indefinite detention of suspected terrorists; the Public Works Protection Act, which was used to detain protesters at the Toronto G20 Summit in 2010; and the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (2002), which enables the routine confinement and detention of stateless refugees and “boat people” arriving in Canada.

Not all political exception results from political violence. Natural disasters and contagious epidemics or pandemics have also resulted in declarations of emergency and the implementation of emergency measures. In the case of disease outbreaks, historically many states have laws that enabled them to evoke extraordinary powers to order quarantines, detain the sick, and seize assets as required. In Canada, the global COVID-19 pandemic, declared in March 2020, resulted in several provinces declaring a state of emergency for limited periods of time. Rather than total quarantine, what this entailed in practice was a series of temporary measures including requiring infected persons or travelers arriving from other countries to self-isolate, closing schools and places of indoor gathering (restaurants, bars, gyms, arenas, etc.), requiring masks for places of indoor gathering, requiring vaccines for certain categories of employment and entry to places of indoor gathering, as well as restrictions on non-necessary travel and contact with people outside one’s immediate social bubble (Lawson et al., 2022).

The federal government also enacted the Emergency Act in 2022 to grant police extra powers to seize assets and remove anti-mask and anti-vaccine activists from their occupation of Ottawa and several blockades of U.S./Canada border crossings. Although the powers granted under public order emergencies like this are limited compared to the former War Measures Act (see text box below), it serves as an interesting example of the normalization of exception after a period of prolonged public health emergency. With the role of disinformation and conspiracy theories, the state and the protesters did not appear to share a common factual basis to engage in political dialogue. To the degree that democratic discourse becomes fragmented in this way, it is probable that evidence-based decision making and the norm of the ideal speech situation discussed earlier in the chapter will be ineffective, making the declaration of political exceptions and use of emergency measures more likely over time.

Making Connections: Big Picture

What are the Powers of the Federal Emergencies Act?

The Emergencies Act is the law that grants the federal government emergency powers in times of crisis. It replaced the War Measures Act that the Pierre Trudeau government used during the October Crisis of 1970. Before it can be evoked, the federal government is required to consult with provinces and territories.

The act defines a national emergency as “an urgent and critical situation of a temporary nature” that:

- Seriously endangers the lives, health or safety of Canadians and is of such proportions or nature as to exceed the capacity or authority of a province to deal with it; or

- Seriously threatens the ability of the Government of Canada to preserve the sovereignty, security, and territorial integrity of Canada (Government of Canada, 1985).

It gives special powers to the Prime Minister or Cabinet to respond to (1) public welfare emergencies like natural disasters and disease outbreaks, (2) public order emergencies like threats to the security of Canada, (3) international emergencies involving threat of violence and (4) war.

In a public-order emergency, like the occupation of Ottawa and border crossings in 2022, the federal cabinet is authorized to give five types of orders:

- The ability to regulate or prohibit public assembly that may reasonably be expected to lead to a breach of the peace, travel, or the use of property.

- The ability to designate and secure protected places.

- The ability to assume the control, restoration and maintenance of public utilities and services.

- The ability to authorize or direct the provision of essential services or the provision of reasonable compensation.

- The ability to impose on summary conviction a fine not exceeding $500 or imprisonment not exceeding six years; or on indictment a fine not exceeding $5,000 or imprisonment not exceeding five years (Government of Canada, 1985).

Media Attributions

- Figure 17.19 Dawn of the Planet of the Apes by Global Panorama, via Flickr, is used under CC BY SA 2.0 licence.

- Figure 17.20 Valiant Shield – B2 Stealth bomber from Missouri leads ariel formation, by Jordon R. Beesley, US Navy, via Wikimedia Commons, is in the public domain.

- Figure 17.21 “FLQ oui” (FLQ yes) by Harryzilber, via Wikimedia Commons, used under a CC BY SA 3.0 licence.

- Figure 17.22 Freedom Convoy 2022, Ottawa, Canada (February 12, 2022) by Maksim Sokolov (Maxergon), via Wikimedia Commons, is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 licence.