18.2 Social Movements

William Little and Ron McGivern

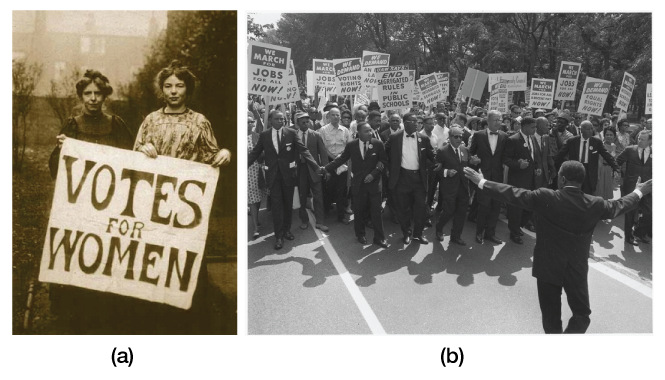

Social movements are purposeful, organized groups striving to work toward a common social goal. While most students learn about social movements in social studies classes, people tend to take for granted the fundamental changes in society they have produced: the rise of capitalism through the early modern bourgeois movements, the splintering of Christianity through the Protestant movements, the development of democracy through revolutionary social movements (the English, French and American revolutions), the development of fascism through white supremacist and nationalist movements, the recognition of gender equality through the Suffragette movements, the transformation of working conditions and provision of social and health security through workers movements, the end of slavery through the abolitionist movements, the extension of civil liberties to various racialized, ethnic and sexual minorities through civil rights movements, etc. Many of the fundamental aspects of modern society no longer appear to be in movement because of the success of social movements. Many other fundamental issues are still being contested. But from the anti-tobacco movement that has worked to outlaw smoking in public spaces, to the environmental movement that is replacing the fossil fuel economy with renewable resources, contemporary movements create social change on a global scale.

Levels of Social Movements

Movements happen at the level of towns, regions, nations and the world. The following examples of social movements range from local to global. No doubt students can think of others on all of these levels, especially since modern technology has provided a near-constant stream of information about the quest for social change around the world. Some movements capture a moment only to fade away, whereas others persist or refocus their activities and remain in the public eye.

Local

Winnipeg’s inner city is well known for its poor Aboriginal population, low levels of income and education, and concerns about drugs, gangs, and violence. Not surprisingly, it has been home to a number of social movements and grassroots community organizations over time (Silver, 2008). Currently, the Winnipeg Boldness Project is a social movement focused on providing investment in early childhood care in the Point Douglas community to try to break endemic cycles of poverty. Statistics show that 40% of Point Douglas children are not ready for school by age five and one in six are apprehended by child protection agencies. Through programs that support families and invest in early childhood development, children could be prepared for school and not be forced into the position of having to catch up to their peers (Roussin, Gill, and Young, 2014). The organization seeks to “create new conditions to dramatically transform the well-being of young children in Point Douglas” (Winnipeg Boldness Project, 2014).

Regional

At the other end of the political spectrum from the Winnipeg Boldness Project is the legacy of the numerous conservative and extreme right social movements of the 1980s and 1990s that advocated the independence of Western Canada from the rest of the country. The Western Canada Concept, Western Independence Party, Confederation of Regions Party, and Western Block were all registered political parties representing social movements of western alienation.

The federal government’s National Energy Program of 1980 was one of the key catalysts for this movement because it was seen as a way of securing cheap oil and gas resources for central Canada at the expense of Alberta. However, the seeds of western alienation developed much earlier in the century with the legitimate perception that Canadian federal politics was dominated by the interests of Quebec and Ontario. The independent farmer parties and the federal Progressive Party of the 1920s and 1930s were based on radical, socialist prairie farmer’s groups that initially united against federal tariff structures that hurt farmer’s livelihoods and hindered the marketing of agricultural products (Bell, 2002; 2007).

One of the more infamous leaders of the Western Canada Concept was Doug Christie who made a name for himself as the lawyer who defended the Holocaust-deniers Jim Keegstra and Ernst Zundel in well-publicized trials in the 1980s. Part of the program of the Western Canada Concept, aside from western independence, was to end non-European immigration to Canada and preserve Christian and European culture. In addition to these extreme-right concerns, however, were many elements of democratic reform and fiscal conservativism, such as mandatory balanced-budget legislation and provisions for referenda and recall legislation (Western Canada Concept, N.d.), which later became central to the federal Reform Party. The Reform Party was western based but did not seek western independence. Rather it sought to transform itself into a national political party eventually forming the Canadian Alliance Party with other conservative factions. The Canadian Alliance merged with the Progressive Conservative Party to form the Conservative Party of Canada in 2003, but the problem of regionalism and Western Canada representation remains a source of instability within the party.

The western alienation movements of the 1980s consolidated an amalgam of concerns recognizable in the 21st century as the white nationalist movement.

National

A prominent national social movement in recent years is Idle No More. A group of aboriginal women organized an event in Saskatchewan in November 2012 to protest the Conservative government’s C-45 omnibus bill. The contentious features of the bill that concerned aboriginal people were the government’s lack of consultation with them in provisions that changed the Indian Act, the Navigation Protection Act, and the Environmental Assessment Act. A month later Idle No More held a national day of action and Chief Theresa Spence of the Attawapiskat First Nation began a 43-day hunger strike on an island in the Ottawa River near Parliament Hill. The hunger strike galvanized national public attention on aboriginal issues, and numerous protest events such as flash mobs and temporary blockades were organized around the country.

One of Chief Spence’s demands was that a meeting be set up with the prime minister and the Governor General to discuss aboriginal issues. The inclusion of the Governor General — the Queen’s representative in Canada — proved to be the sticking point in arranging this meeting, but was central to Idle No More’s claims that aboriginal sovereignty and treaty negotiations were matters whose origins preceded the establishment of the Canadian state. Chief Spence ended her hunger strike with the signing of a 13-point declaration that demanded commitments from the government to review Bills C-45 and C-38, ensure aboriginal consultation on government legislation, initiate an inquiry into missing aboriginal women, and improve treaty negotiations, aboriginal housing, and education, among other commitments (CBC, 2013a; 2013b).

Comparisons between Idle No More and the recent Occupy Movement emphasized the diffuse, grassroots natures of the movements and their non-hierarchical structures. Idle No More emerged outside, and in some respects in opposition to, the Assembly of First Nations. It was more focused than the Occupy Movement in the sense that it developed in response to particular legislation (Bill C-45), but as it grew it became both broader in its concerns and more radical in its demands for aboriginal sovereignty and self-determination. It was also seen to have the same organizational problems as the Occupy movement in that the goals of the movement were left more or less open, the leadership remained decentralized, and no formal decision-making structures were established. Some members of the Idle No More movement were satisfied with the 13-point declaration, while others sought more radical solutions of self-determination outside the traditional pattern of negotiating with the federal government.

It is not clear that Idle No More, as a social movement, will move toward a more conventional social-movement structure or whether it will dissipate and be replaced by other aboriginal movements (CBC, 2013c; Gollom, 2013). Taiaiake Alfred’s post-mortem of the movement was that “the limits to Idle No More are clear, and many people are beginning to realize that the kind of movement we have been conducting under the banner of Idle No More is not sufficient in itself to decolonize this country or even to make meaningful change in the lives of people” (2013). Instead of the focus on demonstrations, media publicity and making representations to the federal government, which “has not responded or felt the need to address [the movement] in any way,” Alfred argues for a more direct approach. “Our focus should be on restoring our presence on the land and regenerating our true nationhood. These go hand in hand and one cannot be achieved without the other” (Alfred, 2013).

Global

Global social movements are networks of social movement actors who collaborate across state borders to address shared global concerns. Increasingly they become powerful forces in global governance, including impacting United Nations Climate Change Conferences, establishing Fair Trade initiatives, and working to resettle refugees and migrants.

Greta Thunberg’s one person school strike against government inaction on climate change spread first in Sweden and then around the world, inspiring a teenager-led global climate strike movement sometimes referred to as Fridays for Future. Twenty thousand students – from Canada to Japan – had skipped school to protest the lack of urgency by governments by December, 2018 (Carrington, 2018). As a spokesperson who presents the climate change issue from the perspective of youth’s stolen future, she presents a powerful social movement frame to castigate world leaders and impact global policy. World leaders have had “26 COPs [Conference of the Parties on climate change], they have had decades of blah, blah, blah – and where has that got us?” (Thunberg, cited in Kraemer, 2021).

Despite their successes in bringing forth change on controversial topics, global social movements are not always about volatile politicized issues. For example, the global movement called Slow Food focuses on how we eat as means of addressing contemporary quality-of-life issues. Slow Food, with the slogan “Good, Clean, Fair Food,” is a global grassroots movement claiming supporters in 150 countries. The movement links community and environmental issues back to the question of what is on our plates and where it came from. Founded in 1989 in response to the increasing existence of fast food in communities that used to treasure their culinary traditions, Slow Food works to raise awareness of food choices (Slow Food, 2011). With more than 100,000 members in 1,300 local chapters, Slow Food is a movement that crosses political, age, and regional lines.

Types of Social Movements

Social movements occur on the local, regional, national and global stages; often on all four stages simultaneously. Are there other patterns or classifications that can help to understand them? Sociologist David Aberle (1966) addresses this question, developing categories that distinguish among social movements based on what they want to change and how much change they want. Reform movements seek to change something specific about the social structure. Examples include anti-nuclear groups, Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD), and the National Action Committee on the Status of Women (NAC). Revolutionary movements seek to completely change every aspect of society. These would include Cuban 26th of July Movement (under Fidel Castro), the 1960s counterculture movement, as well as Antifa (short for anti-fascism) and other anarchist collectives. Redemptive movements are “meaning seeking,” and their goal is to provoke inner change or spiritual growth in individuals. Organizations promoting these movements might include Alcoholics Anonymous, New Age, or Christian fundamentalist groups. Alternative movements are focused on self-improvement and limited, specific changes to individual beliefs and behaviour. These include groups like the Slow Food movement, Planned Parenthood, and barefoot jogging advocates. Resistance movements seek to prevent or undo change to the social structure. The Ku Klux Klan, white nationalist, anti-vaxxer and pro-life movements fall into this category.

Stages of Social Movements

Sociologists also study the life cycle of social movements — how they emerge, grow, and in some cases, die out. Blumer (1969) and Tilly (1978) outline a four-stage process. In the preliminary stage, people become aware of an issue and leaders emerge. This is followed by the coalescence stage when people join together and organize in order to publicize the issue and raise awareness. In the institutionalization stage, the movement no longer requires grassroots volunteerism: it is an established organization, typically peopled with a paid staff. When people fall away, adopt a new movement, the movement successfully brings about the change it sought, or people no longer take the issue seriously, the movement falls into the decline stage. Each social movement discussed earlier belongs in one of these four stages. Where do they belong on the list?

Making Connections: Sociology in the Real World

Social Media and Social Change: A Match Made in Heaven?

As mentioned earlier in this chapter, social media is a widely used mechanism in social movements. For example, Tarana Burke first used “Me Too” in 2006 on a major social media venue of the time (MySpace). The phrase later grew into a massive movement when people began using it on Twitter to drive empathy and support regarding experiences of sexual harassment or sexual assault. In a similar way, Black Lives Matter began as a social media message after George Zimmerman was acquitted in the shooting death of 17-year-old Trayvon Martin, and the phrase sparked a formal (though decentralized) social movement.

Social media has the potential to dramatically transform how people get involved in movements ranging from local school district decisions to presidential campaigns. As discussed above, movements go through several stages, and social media adds a dynamic to each of them. In the preliminary stage, people become aware of an issue, and leaders emerge. Compared to movements of 20 or 30 years ago, social media can accelerate this stage substantially. Issue awareness can spread at the speed of a click, with thousands of people across the globe becoming informed at the same time. In a similar vein, those who are savvy and engaged with social media may emerge as leaders, even if, for example, they are not great public speakers.

At the next stage, the coalescence stage, social media is also transformative. Coalescence is the point when people join together to publicize the issue and get organized. US President Obama’s 2008 campaign was a case study in organizing through social media. Using Twitter and other online tools, the campaign engaged volunteers who had typically not bothered with politics. Combined with comprehensive data tracking and the ability to micro-target, the campaign became a blueprint for others to build on. The US 2020 elections featured a level of data analysis and rapid response capabilities that, while echoing the Obama campaign’s early work, made the 2008 campaign look quaint. The campaigns and political analysts could measure the level of social media interaction following any campaign stop, debate, statement by the candidate, news mention, or any other event, and measure whether the tone or “sentiment” was positive or negative. Political polls are still important, but social media provides instant feedback and opportunities for campaigns to act, react, or—on a daily basis and in “real time”—ask for donations based on something that had occurred just hours earlier (Knowledge at Wharton, 2020).

Interestingly, social media can have interesting outcomes once a movement reaches the institutionalization stage. In some cases, a formal organization might exist alongside the hashtag or general sentiment, as is the case with Black Lives Matter. At any one time, BLM is essentially three things: a structured organization, an idea with deep and personal meaning for people, and a widely used phrase or hashtag. It is possible that users of the hashtag are not referring to the formal organization. It is even possible that people who hold a strong belief that Black lives matter do not agree with all of the organization’s principles or its leadership. In other cases, people may be very aligned with all three contexts of the phrase. Social media is still crucial to the social movement, but its interplay is both complex and evolving.

In a similar way, MeToo activists, including Tarana Burke herself, have sought to clarify the interweaving of different aspects of the movement. She told the Harvard Gazette in 2020:

I think we have to be careful about what we’re calling the movement. And I think one of the things I’ve learned in the last two years is that folks don’t really understand what a movement is or how it’s defined. The people using the hashtag on the internet were the impetus for Me Too being put into the public sphere. The media coverage of the viralness of Me Too and the people being accused are media coverage of a popular story that derived from the hashtag. The movement is the work that our organization and others like us are doing to both support survivors and move people to action (Walsh 2020).

Sociologists have identified high-risk activism, such as the civil rights movement, as a “strong-tie” phenomenon, meaning that people are far more likely to stay engaged and not run home to safety if they have close friends who are also engaged. The people who dropped out of the movement—who went home after the danger became too great—did not display any less ideological commitment. But they lacked the strong-tie connection to other people who were staying. Social media had been considered “weak-tie” (McAdam and Paulson, 1993; Brown, 2011). People follow or friend people they have never met. Weak ties are important for contemporary networked social structure, but they seem to limit the level of risk people will take on their behalf. For some people, social media remains that way, but for others it can relate to or build stronger ties. For example, if people, who had for years known each other only through an online group, meet in person at an event, they may feel far more connected at that event and afterward than people who had never interacted before. Social media itself, even if people never meet, can bring people into primary group status, forming stronger ties.

Another way to consider the impact of social media on activism is through something that may or may not be emotional, has little implications regarding tie strength, and may be fleeting rather than permanent, but still be one of the largest considerations of any formal social movement: money. The 2022 “Trucker’s Convoy” that occupied Ottawa and several border crossing to protest COVID-19 public health mandates raised $10 million internationally in a matter of days through a GoFundMe campaign, even though it was not clear what the money would be used for or who was leading the movement. The money was eventually frozen and returned to donors when the criminal and harassing behaviours of the protests violated the terms of GoFundMe service. In general however, 55 per cent of people who engage with nonprofits through social media take some sort of action; and for 60 per cent of them (or 33 per cent of the total) that action is to give money to support the cause (Nonprofit Source 2020).

Theoretical Perspectives on Social Movements

Most theories of social movements are called collective action theories, indicating the purposeful nature of this form of collective behaviour. The following three theories are but a few of the many classic and modern theories developed by social scientists. Resource mobilization theory focuses on the practical, organizational strategies that social movements need to engage in to successfully mobilize support, compete with other social movements and opponents, and present political claims and grievances to the state. Framing theory focuses on the way social movements make appeals to potential supporters by framing or presenting their issues in a way that aligns with commonly held values, beliefs, and commonsense attitudes. New social movement theory focuses on the commonalities shared by many social movements that emerged from the 1960s onwards. These movements shifted focus from the materialist or economic struggles of the 19th and 20th century labour movements, for example, to shed light on new areas concerning the livability or quality of life: environmental integrity, peace and disarmament, holistic health, decolonization, reconciliation, recognition of diversity and opportunities for self-actualization (Habermas, 1981).

Resource Mobilization

Social movements will always be a part of society as long as there are aggrieved populations whose needs and interests are not being satisfied. However, grievances do not become social movements unless social movement actors are able to create viable organizations, mobilize resources and funds, and attract large-scale followings. As people will always weigh their options and make rational choices about which movements to follow, social movements necessarily form under finite competitive conditions: competition for attention, financing, commitment, personnel, organizational skills, etc. Not only will social movements compete for the public’s attention with many other concerns — from the basic (people’s jobs or their need to feed themselves) to the entertaining (video games, sports, or television) — but they also compete with each other. For any individual, it may be a simple matter to decide whether they want to spend their time and money on animal shelters, international disaster relief or fighting public health measures during a pandemic. The question is, however, which animal shelter, which disaster, or which “personal freedom” issue? To be successful, social movements must develop the organizational capacity to attract attention, mobilize resources (money, people, and skills) and compete with other organizations to reach their goals.

McCarthy and Zald (1977) conceptualize resource mobilization theory as a way to explain a movement’s success in terms of its ability to acquire resources and mobilize individuals to achieve goals and take advantage of political opportunities. Whatever the emotional or other substantive reasons people have for joining or creating social movements, in this approach social movements are conceptualized as rational, calculating, goal-oriented social institutions. How groups organize to mobilize resources is at the center of the analysis. Resources in this context include:

- Material Resources such as financing, property, office space, equipment, and supplies.

- Human Resources such as activists, volunteers, staff, as well as their experience, skills, and expertise.

- Social-Organizational Resources such as public infrastructure, digital infrastructure, social networks, and organizational structures.

- Moral Resources such as beliefs and values that movements can draw on and appeal to tin order to create legitimacy, solidarity, and sympathetic support for the movement’s goals.

- Cultural Resources such as collective understanding of the issues, social movement “know-how,” and organizational templates.

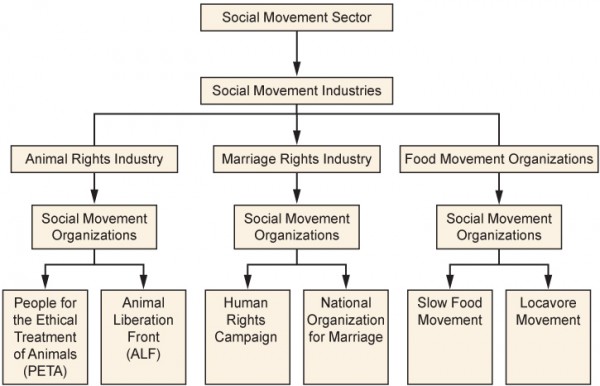

For example, People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) is a social movement organization (SMO) in competition for these five types of resource with Greenpeace and the Animal Liberation Front (ALF), two other social movement organizations engaged with animal rights.

Taken together, along with all other social movement organizations working on animals rights issues, these similar organizations constitute a social movement industry. In keeping with the economic analogy of resource mobilization, a social movement industry is similar to the many industrial categories of firms that compose an economy. Where resources are limited, there is competition between social movement organizations.

Whether we study revolutionary movements, broad or narrow social reform movements, or religious movements, we find a variety of SMOs or groups, linked to various segments of supporting constituencies (both institutional and individual), competing amongst themselves for resources and symbolic leadership, sharing facilities and resources at other times, developing stable and many times differentiated functions, occasionally merging into unified ad hoc coalitions, and occasionally engaging in all – out war against each other (Zald and McCarthy, 1987).

Multiple social movement industries in a society, though they may have widely different constituencies and goals, constitute a society’s social movement sector. Every social movement organization (a single social movement group) within the social movement sector is competing for the public’s attention, time, and resources. The chart in Figure 18.13 shows the relationship between these components.

Framing/Frame Analysis

The sudden emergence of social movements that have not had time to mobilize resources, or vice versa, the failure of well-funded groups to achieve effective collective action, calls into question the emphasis on resource mobilization as an adequate explanation for the formation of social movements. Over the past several decades, sociologists have developed the concept of frames to explain how individuals identify and understand social events and which norms they should follow in any given situation (Benford and Snow, 2000; Goffman, 1974; Snow et al., 1986).

Frames are ways in which experience is organized conceptually. They are “schemata of interpretation,” which allow individuals to make sense of situations, information, or experiences. As Goffman describes, “each primary framework allows its user to locate, perceive, identify, and label a seemingly infinite number of concrete occurrences defined in its terms” (Goffman, 1974).

Imagine a framed painting in an art gallery. The painting’s frame is what separates the artwork from the wall and makes it stand out. The frame says essentially, “Look at this, this is significant, this is art.” It draws the viewer’s attention to specific details and provides the viewer with a behaviour template about how to approach the painting, the attitude to take, the state of mind to be in to receive the painting’s meaning or message, etc. It frames a piece of experience, which the artist has depicted, and invites the viewer to see their own life and experience through it. Similarly, social movements must actively engage in realigning collective social frames so that the movements’ interests, ideas, values, and goals become congruent with those of potential members. The movements’ goals have to make sense to people to draw new recruits into their organizations.

Successful social movements use three kinds of frames (Snow and Benford, 1988) to further their goals. The first type, diagnostic framing, states the social movement problem in a clear, easily understood way. When applying diagnostic frames, there are no shades of grey: instead, there is the belief that what “they” do is wrong and this is how “we” will fix it. The anti-gay marriage movement is an example of diagnostic framing with its uncompromising insistence that marriage is only between a man and a woman. Any other concept of marriage is framed as sinful or immoral. Prognostic framing, the second type, offers a solution and states how it will be implemented. When looking at the issue of pollution as framed by the environmental movement, for example, prognostic frames could include direct legal sanctions like fines on polluters, enforcement of strict government regulations on polluting activities, or the imposition of carbon pricing or cap-and-trade mechanisms to make environmental damage more costly. There may be many competing prognostic frames even within social movements adhering to similar diagnostic frames. Finally, motivational framing is the call to action: what should an individual do once they agree with the diagnostic frame and believe in the prognostic frame? These frames are action-oriented. In the aboriginal justice movement, a call to action might encourage people to join a blockade on contested aboriginal treaty land or contact their local MP to express their viewpoint that aboriginal treaty rights be honoured.

With so many similar diagnostic frames, some groups find it best to join together to maximize their impact. When social movements link their goals to the goals of other social movements and merge into a single group, a frame alignment process (Snow et al., 1986) occurs — an ongoing and intentional means of recruiting a diversity of participants to the movement. For example, Carroll and Ratner (1996) argue that using a social justice frame makes it possible for a diverse group of social movements — union movements, environmental movements, aboriginal justice movements, gay rights movements, anti-poverty movements, etc. — to form effective coalitions even if their specific goals do not typically align.

This frame alignment process involves four aspects: bridging, amplification, extension, and transformation. Bridging describes a “bridge” that connects uninvolved individuals and unorganized or ineffective groups with social movements that, though structurally unconnected, nonetheless share similar interests or goals. These organizations join together creating a new, stronger social movement organization. What are some examples of different organizations with a similar goal that have banded together?

In the amplification model, organizations seek to expand their core ideas to gain a wider, more universal appeal. By expanding their ideas to include a broader range, they can mobilize more people for their cause. For example, the Slow Food movement extends its arguments in support of local food to encompass reduced energy consumption and reduced pollution, plus reduced obesity from eating more healthfully, and other benefits.

In extension, social movements agree to mutually promote each other, even when the two social movement organization’s goals do not necessarily relate to each other’s immediate goals. This often occurs when organizations are sympathetic to each others’ causes, even if they are not directly aligned, such as women’s equal rights and the civil rights movement.

Transformation involves a complete revision of goals. Once a movement has succeeded, it risks losing relevance. If it wants to remain active, the movement has to change with the transformation or risk becoming obsolete. For instance, when the women’s suffrage movement gained women the right to vote, they turned their attention to equal rights and campaigning to elect women. In short, it is an evolution to the existing diagnostic or prognostic frames generally involving a total conversion of movement.

New Social Movement Theory

New social movement theory emerged in the 1970s to explain the proliferation of new movements that focused on quality of life issues and were difficult to analyze using traditional social movement theories (Melucci, 1989; Habermas, 1981). Rather than being based on the grievances of particular groups striving to influence political outcomes or redistribute material resources, new social movements (NSMs) like the peace and disarmament, environmental, and 2nd/3rd wave feminist movements focus on goals of autonomy, identity, self-realization, and quality-of-life: who people are, how people live. As the German Green Party slogan of the 1980s suggests — “We are neither right nor left, but ahead” — the appeal of the new social movements also tends to cut across traditional class, party politics, and socioeconomic affiliations to contest aspects of everyday life traditionally seen as outside politics. Moreover, the movements themselves are more flexible, diverse, shifting, and informal in participation and membership than the older social movements, often preferring to adopt nonhierarchical modes of organization and unconventional means of political engagement (such as direct action).

Melucci (1994) argues that the commonality that designates these diverse social movements as “new” is the way in which they respond to systematic encroachments on the lifeworld, the shared inter-subjective meanings and common understandings that form the backdrop of daily existence and communication. The dimensions of existence that were formally considered private (e.g., the body, sexuality, interpersonal affective relations), subjective (e.g., desire, motivation, and cognitive or emotional processes), or collective commons (e.g., nature, urban spaces, language, information, and communicational resources) are increasingly subject to social control, manipulation, commodification, and administration. However, as Melucci (1994) argues,

These are precisely the areas where individuals and groups lay claim to their autonomy, where they conduct their search for identity…and construct the meaning of what they are and what they do (Melucci, 1994).

Foucault (1994) summarizes the common features of the new social movements:

- They are transversal movements, not limited to one country or to a particular political or economic form of government

- They target the direct experience of the exercise of power. For example, alternative health movements do not criticize the medical profession because it makes profit from people’s illnesses, but because of the ways it directly exercises power over people’s bodies and health.

- They are therefore focused on immediate issues, criticizing types of power exercised directly on individuals rather than distant or mediated sources of power like the state or the capitalist class, and seek immediate and practical solutions rather than complete liberation or revolutionary transformation at a later date.

- They are struggles about the status of the individual in society: the right to be different and to pursue self-actualization; the rejection of disciplinary practices that separate, isolate, mould and institutionalize individuals.

- They challenge the use of expert knowledge and science in the exercise of power.

- They focus on the question: Who are we? They assert a right to self-identify and reject scientific or administrative definitions that determine who one is.

As Foucault puts it, the new social movements are movements that are principally concerned with the various means by which individuals are directly subjected to power today. “There are two meanings of the word “subject”: subject to someone else by control and dependence, and tied to his own identity by a conscience or self-knowledge” (Foucault, 1994). In other words, people form new social movements to address distinct concerns in the areas of gender, health, the administration of life, etc., because of the various ways in which modern power relations undermine their sense of autonomy and attempt to regulate their personal life and subjectivity. They are not easily categorized into the “right” and “left” categories that have characterized the political spectrum since the democratic revolutions of the 18th century.

Summary: Functionalist, Critical, and Interpretive Perspectives on Social Movements

What do ISIS, Antifa, old growth logging protests, People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA), the anti-globalization movement, and white nationalists have in common? Not much, one might think. But although they may be left-wing or right-wing, radical or conservative, highly organized or very diffused, they are all examples of social movements that create change in society.

Consider the effect of the 2010 Enbridge oil spill on the Kalamazoo River in Michigan. This disaster exemplifies how an aging pipeline infrastructure, coupled with inadequate pipeline technology, combined with anti-oil sentiment in social movements and social institutions, led to changes in oil pipeline policies. Subsequently, in an effort to support the cleanup of the Kalamazoo River and to prevent similar disasters, changes to pipeline safety and spill response occurred. From Aboriginal movements that challenge the use of traditional territories as conduits for petroleum products, to environmental movements who protest further pipeline and fossil fuel development in a period of climate change, to municipal governments who respond to residents concerned with the local risks of oil spills, organizations develop and shift to meet the changing needs of the society. Just as with the Kalamazoo River oil spill and the 10 year project to dredge and rehabilitate the river, social movements have, throughout history, influenced societal shifts. Sociology looks at these moments through the lenses of three major perspectives.

The structural functionalist perspective looks at society as a social system, focusing on the way that all aspects of society have functions that are integral to the continued health and viability of the whole. A functionalist might focus on why social movements develop, why they continue to exist, and what social purposes they serve. On one hand, social movements emerge when there is a dysfunction in the relationship between components of the social system. The union movement developed in the 19th century when the organization of the economy persistently failed to distribute wealth and resources in a manner that provided adequate sustenance for workers and their families. On the other hand, when studying social movements themselves, functionalists observe that movements must change their goals as initial aims are met or they risk dissolution. To function, they must adapt. Several organizations associated with the anti-polio movement folded after the creation of an effective vaccine that made the disease virtually disappear. In the absence of strong advocates of vaccines, segments of the population forgot about the dangers of infectious diseases. Yet, contemporary organizers of the anti-vaccine and anti-masking movement achieved their greatest organizational success with the “Freedom Convoy” in early 2022, just weeks before governments removed public health measures due to declining public health risks. They achieved success at the moment they were no longer relevant. How do social movement organizations adapt and keep their movements alive when their issues are no longer top of mind?

Critical sociology focuses on the creation and reproduction of inequality and power relations in society. Someone applying the critical perspective would likely be interested in how social movements are generated as responses to systematic inequality or marginalization. They would see social change as unavoidable because unresolved conflict is built in to society’s structures. Conflict drives social change. For example, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) was founded in the United States in 1908. Partly created in response to the horrific lynchings occurring in the southern United States, the organization fought to secure the constitutional rights guaranteed in the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments, which established an end to slavery, equal protection under the law, and universal male suffrage (NAACP, 2011). While those formal legal goals have been achieved, the organization remains active today advocating for changes in policy and law because inequalities in civil rights and discriminatory practices have not disappeared. Its efforts can be supplemented by emergent social movements like Black Lives Matter, which are better positioned to channel outrage in response to events like Trayvon Martin and George Floyd’s murders. Whereas the conflict over racial discrimination endures through time because it remains unresolved, it can become more urgent and focused at times, opening a space for social movement innovations.

The interpretive perspective studies how the meanings and frames of social movements evolve. This includes the day-to-day processes and interactions of social movements, the meanings individuals attach to involvement in such movements, and the individual experience of social change. A symbolic interactionist studying social movements might address the emergence of social movement norms and tactics as well as the formation of individual motivations in concert with others. For example, social movements might be generated through a collective experience of deprivation or discontent embedded in the power relations of society, but how does deprivation get framed in a way that motivates people to take risks to confront power structures? On the other hand, people might actually join social movements for a variety of reasons that have nothing to do with the cause. They might want to feel part of something important, or they might know someone in the movement they want to support, or they might just feel an affinity with the subculture of rebellion. Students might ask themselves whether they have ever been motivated to show up for a rally or sign a petition because their friends invited them? Would they have been as likely to get involved otherwise?

Making Connections: Sociology in the Real World

The Rise of White Nationalism

Contemporary white nationalism is a complex social movement that emerged in the 1980s but has become especially prominent in the 21st century across Europe and North America. From overtly racial attacks and hate speech, to counter-protesting Antifa and the Black Lives Matter movements, to loose coalitions with anti-vaxxers and anti-taxation movements to defend “freedom,” white nationalism is firmly part of 21st century society’s social movement sector. It resembles historical white supremacist, reactionary, fascist and populist movements but also diverges from them significantly.

In Wendy Brown’s (2019) analysis, white nationalism represents a new formation of subjectivity and politics that has to be understood in the context of contemporary populist politics, neoliberal economic restructuring, aggrieved white privilege and culture. She describes it as a “curious combination of libertarianism, moralism, authoritarianism, nationalism, hatred of the state, Christian conservatism, and racism;” curious because many of these ideas seem to contradict one another. She identifies three key elements that define what is new and unique about contemporary white nationalism: the economic context globalization, the neoliberal framing of threats to personal liberty and the unprecedented public social disinhibition and aggression of the movement.

The economic context of the rise of white nationalism is the global neoliberal restructuring of economic life. Neoliberalism emphasizes the use of “free market” mechanisms to regulate society (see Chapter 4. Society and Modern Life, Chapter 10. Global Society , and Chapter 17. Government and Politics). The unrestricted global flows of capital investment and disinvestment produce economic and political inequalities and instability: the dismantling of Fordist era livable incomes, job security, retirement provisions, and publicly funded education, services, and other social goods. The wealth inequality of neoliberal privatization has “more deeply penetrated into everyday life than at any time since feudalism” (Brown, 2019). Especially hard hit in North America have been the manufacturing industries, which had provided well paying, often unionized jobs, for a largely male labour force with limited education. The uneven effects of neoliberal restructuring provide a source of hardship, uncertainty, discontent and grievance, especially among white workers who perceive racialized Others as either “stealing” jobs by working for low wages or unfairly “getting ahead” through preferential hiring and affirmative action programs.

The second element is the diagnostic framing of neoliberalism: the libertarian idea that personal freedom and liberty are threatened by the state or by historically marginalized groups demanding justice and equality. This leads to the prognostic framing or solution that “the personal protected sphere must be extended” (Brown, 2019). Neoliberal theorists like Friedrich Hayek (1899-1992) and Milton Friedman (1912-2006) argue that both markets and religious or moral traditions were spontaneously generated sources of social order. Both were components of a private personal sphere of activity that should be protected from external interference, public policy and even democratic decision making. So while freedom, as the unregulated personal licence of the individual, seems to contradict submission to customary prejudices and traditional authorities (moral, religious, familial, etc.), in neoliberalism both are components of the sphere of private life that need to be extended and protected. Authoritianism and freedom can thereby be reconciled. In white nationalism, the nation itself becomes an extended personal sphere — a “Chez Nous” as French National Front leader Marie Le Pen calls it — that needs to be defended, even by authoritarian means, against threatening outsiders or those within who do not belong.

This framing appeals especially to the segment of the population who have enjoyed white privilege (see Chapter 11. Race and Ethnicity) because they regard their everyday personal freedoms as normal and any perceived challenge to them is threatening, as opposed to minorities and subordinated populations who have historically not had access to freedom, or routinely see their freedoms arbitrarily suspended or denied.

This leads to the third element of white nationalism in Brown’s analysis, which is the affective or emotional tone of the movement; its celebration of disinformation, its amoral and uncivil conduct, and its disinhibition and aggression. The underlying emotion of the movement is the feeling of resentment, “suffering experienced as wrongful victimization” (Brown, 2019). The source what she calls the movement’s “politics of resentment” stems from a feeling of powerlessness amongst formally dominant segments of the population. “This politics of ressentiment emerges from the historically dominant as they feel that dominance ebbing—as whiteness, especially, but also masculinity provides limited protection against the displacements and losses that forty years of neoliberalism have yielded for the working and middle classes” (Brown, 2019). The uninhibited rage directed against something relatively trivial like taking a vaccine shot or wearing a mask during a pandemic makes sense as an act of “taking a stand” simply to feel having power over something when world affirmation or world building are unavailable.

Image Descriptions

Figure 18.13 long description: The social movement sector is made of various social movement industries. Social movement industries are made up of related social movement organisations. To show the relationship:

1. People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) and the Animal LIberation Front (ALF) are social movement organizations within the Animal Rights Industry.

2. The Humans Rights Campaign and the National Organization for Marriage are social movement organizations within the Marriage Rights Industry.

3. The Slow Food Movement and the Locavore Movement are social movement organizations within the Food Movement organizations. [Return to Figure 18.13]

Media Attributions

- Figure 18.9 Flag of western Canada by Harley King, via Wikimedia Commons, is used under a CC BY SA 3.0 licence.

- Figure 18.10 #IdleNoMore by AK Rockefeller, via Flickr, is used under a CC BY SA 2.0 licence.

- Figure 18.11 Greta Thunberg, outside the Swedish parliament by Anders Hellberg, via Wikimedia Commons, is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 licence.

- Figure 18.12 Black Lives Matter – We Won’t Be Silenced – London’s Oxford Circus – 8 July 2016 by Alisdare Hickson, via Flickr, is used under a CC BY-NC 2.0 licence.

- Figure 18.13 Figure 1. The connotation of green sports in the new era 2021 by Liying Zhang, 2021, is used under a CC BY 3.0 licence.

- Figure 18.14 (a) Annie Kenney and Christabel Pankhurst by unknown author, via Wikimedia Commons; and (b) March on washington Aug 28 1963 by unknown photographer, U.S. Information Agency. Press and Publications Service. (ca. 1953 – ca. 1978), National Archives Collection, are in the public domain.

- Figure 18.15 Freedom Convoy 2022, Ottawa, Canada (February 12, 2022) by Maksim Sokolov, via Wikimedia Commons, is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 licence.

- Figure 18.16 Aryan Guard in Kensington by Thivierr, via Wikimedia Commons, is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 licence.