20.3 The Environment and Society

The subfield of environmental sociology studies how humans interact with their environments. This field is closely related to human ecology, which focuses on the relationship between people and their built and natural environment. As extreme weather patterns and policy battles over climate change dominate the news, environmental sociology is garnering more attention as a source of solutions for how to address these issues.

Environmental sociologists emphasize two important dimensions of the relationship between society and the environment: (a) the impact of human activity and decision making and (b) the existence and consequences of environmental inequality and environmental racism.

The primary point of analysis has to do with the ways in which human activity transforms the natural environment and human interactions with other species. Two key concepts in environmental sociology are the concepts of carrying capacity, which refers to the maximum amount of life that can be sustained within an area given the limited amount of natural resources available, and the commons, which refers to the collective resources that humans share in common. These collective resources are typically shared natural resources like air, water, plant and animal life, or ecosystems that have remained outside of private ownership or processes of commodification and trade.

In an environmental context, the carrying capacity of different environments depends on the commons to the degree that the commons are necessary for sustaining life. When the commons are threatened through pollution or over-exploitation the carrying capacity of the environment is degraded. While both concepts can refer to a number of ecological variables from local grazing lands or to rivers, they can also be applied to the Earth as a whole. Climate change is a global issue in which the degradation of the global commons through ecologically unsustainable human activities threatens the earth’s carrying capacity as a whole. Practical research in the area of environmental sociology focuses therefore on identifying the threats human societies pose to the carrying capacity of ecosystems they are embedded in as well as modifications to human practices to make them more environmentally sustainable.

Making Connections: The Big Picture

The Tragedy of the Commons

The expression “the tragedy of the commons” was the title of an article written by Garrett Hardin in 1968, which described how a common pasture is ruined by overgrazing. In England, “the commons” referred to land that the community held in common. Hardin was not the first to notice the phenomenon. Back in the 1800s, Oxford economist William Forster Lloyd looked at the devastated public grazing commons and the unhealthy cattle subject to such limited grazing, and saw, in essence, that the carrying capacity of the commons had been exceeded. However, since no one held personal responsibility for the land (as it was open to all), no one was willing to make sacrifices to improve it.

This is a classical problem of the collective outcome of individual “rational” choices. If each user makes a rational choice by weighing their individual costs and benefits with respect to the use of common resources, the collective outcome ultimately undermines each user’s individual ability to benefit from the common resource. Their individual rational choices have an irrational collective outcome. Cattle grazers benefited from adding more cattle to their herd, but they did not have to take on the responsibility of the destroyed lands that were being damaged by overgrazing. There was an incentive for them to add more head of cattle, and no incentive for restraint.

Satellite photos of Africa taken in the 1970s showed this practice to dramatic effect. The images depicted a dark irregular area over 300 miles around. When seen from above, there was a large, fenced area, where plenty of grass was growing. Outside the fence, the ground was bare and devastated. The reason was simple: the fenced land was privately owned by informed farmers who carefully rotated their grazing animals and allowed the fields to lie fallow periodically. Outside the fence was land used by nomads. The nomads, like the herders in 1800s Oxford, increased their heads of cattle without planning for its impact on the greater good. The soil eroded, the plants died, then the cattle died, and, ultimately, some of the people died.

Hardin made an argument that the privatization of the commons would be the logical solution to overgrazing and similar issues of over-exploitation. Only an owner would be motivated to care properly for property and resources in which they were personally invested. Others argue that private ownership of property is the problem because resources are only seen as commodities to exploit for private profit. This is seen as an incentive for state regulation of the use of collective resources (Ostrom, 1990). In fact, closer examination of Hardin’s example of the common pastures of England reveal that the communities were able to manage their commons for centuries until the Enclosure Acts between 1750 and 1850, which forced peasants off the land (Cox, 1985). The locals were not stupid and were able to regulate themselves to ensure the viability of their common resource and their own survival. The examples of overgrazing the commons were the result of large landowners deliberately over-utilizing the common resource so that they would fail and then could be privatized.

How does this affect those who do not need to graze their cattle? Well, like the cows, people all need food, water, and clean air to survive. With the increasing consumption of resources in the West, increasing world population, and the ever-larger megalopolises with tens of millions of people, the limit of Earth’s carrying capacity or collective commons is called into question. Earth’s carrying capacity is itself the global commons. As in the tragedy of the commons Hardin described for the pasturelands of England, each economic and state actor in the world has an interest in maximizing its own economic benefit from exploiting the environment with little compelling incentive to conserve it in the global interest. Whether for cattle or humans, when too many take with too little thought to the rest of the population, the result is usually tragedy.

Climate Change and Society

This section adapted from Islam and Kieu (2021). CC BY-NC 4.0

Climate change refers to long-term shifts in temperatures due to human activity, particularly the release of greenhouse gases into the environment. It is a critical problem, spanning across societal boundaries and socioeconomic divisions. While the planet as a whole is on average warming––hence the term global warming––short-term variations of climate change can include both higher or lower temperatures and tendencies more extreme weather. There are increasingly more record-breaking weather phenomena, from “atmospheric rivers” of torrential rain causing flooding to “heat domes” causing periods of dangerously high temperatures and forest fires.

Due to the wide-ranging and deep-seated nature of its causes, researchers and policymakers face a massive task coordinating effective and developing policies to mitigate its impacts. While the scientific community has made good progress in developing an ecological imagination related to climate change, environmental sociology focuses on developing a sociological imagination to analyze these issues. “The application of a sociological imagination allows us to powerfully reframe four central questions in the current interdisciplinary conversation on climate change: why climate change is happening, how we are being impacted, why we have failed to successfully respond so far, and how we might be able to effectively do so” (Norgaard, 2018).

The comprehensive Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Report released in 2023 made 10 key findings on the causes and impacts of climate change (IPCC, 2023; Boehm and Schumer, 2023).

- Human-induced global warming of 1.1 degrees C has spurred changes to the Earth’s climate that are unprecedented in recent human history. These changes include glacial retreats unmatched in over 2,000 years, sea level rising faster than any previous century in 3,000 years, last decade warmer than any period for 125,000 years.Additional warming will increase the magnitude of these concerns.

- Climate impacts on people and ecosystems are more widespread and severe than expected, and future risks will escalate rapidly with every fraction of a degree of warming. About half the global population contend with severe water scarcity for at least a month per year and higher temperatures increase the spread of diseases such as malaria. Climate change has also slowed agricultural productivity improvements e.g., crop productivity growth in Africa has shrunk by a third since 1961. Since 2008 extreme floods and storms have forced over 20 million people from their homes every year. Even limiting global warming to 1.5oC does not guarantee safety, as at this level of warming, 950 million people will be subjected to water and heat stress.

- Adaptation measures can effectively build resilience, but more finance is needed to scale solutions. At least 170 countries are considering adaptation measures, but often progress from planning to implementation is slow. Building resilience measures are often small-scale, reactive and focused on near-term risks. This is often due to limited financing, especially in developing countries.

- Some climate impacts are already so severe they cannot be adapted to, leading to losses and damages. Globally, vulnerable people are struggling to adapt to climate impacts. In some cases, the limitations are ‘soft’ due to economic, political or social obstacles. In other cases, the adaptation limits are becoming ‘hard’ with climate change impacts becoming so frequent and severe that existing adaptation strategies cannot fully avoid losses and damages, e.g., rising sea temperatures affecting coral reef systems and associated livelihood and food security, and rising sea levels affecting habitation. Urgent action is needed to address the resulting losses and damages. COP27 saw some agreement to funding arrangements, but this needs to be actioned.

- Limiting global warming to 1.5oC this century requires deep global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions reductions before 2025. There is more than a 50% chance that 1.5oC global warming will be reached or passed by 2040. Without sufficient emissions reductions (43% by 2030, and 60% by 2035,relative to 2019 levels), global warming could reach 3.3oC to 5.7oC by 2100. Such global temperature levels last occurred over 3 million years ago. While there has been a reduction in the growth of emissions from the 2000s to the 2010s (2.1% growth falling to 1.3%), this is way below the reductions needed. Even if countries achieved their climate pledges the GHG emission reduction would be 7% by 2030, rather than the 43% needed.

- The world must rapidly shift away from burning fossil fuels – the number one cause of the climate crisis. Strategies to avoid locking in these excess emissions include retiring existing fossil fuel infrastructure, cancelling new projects and retrofitting carbon capture and storage technologies to existing power plants., while at the same time scaling up renewable energy sources like wind and solar (now both generally cheaper than fossil fuels).

- The world needs urgent, system-wide transformations beyond fossil fuel reductions to secure a net-zero, climate-resilient future. While fossil fuels are the number one source of GHG emissions, deep cuts are needed across society to limit emissions. Power generation, buildings, industry, and transport account for nearly 80% of emissions, with agriculture, forestry, and land usage accounting for the balance. For example, the transport system requires planning to minimise the need for travel, building shared and public transport, increasing the supply and affordability of electric private and commercial vehicles and buses. This needs to be supported by widespread rapid-charging infrastructure and zero-carbon fuels for shipping and aviation. Policy measures can help drive necessary transitions such as subsidising zero-carbon technologies and taxing high-emission technologies, e.g., fossil fuel vehicles.

- Carbon removal is now essential to limit global temperature rise to 1.5oC. This could be by way of natural solutions such as sequestering and storing carbon in trees and soil, e.g., afforestation, as well as innovative technologies that pull CO2 from the air. An example of a technological solution is carbon mineralisation which uses reactive minerals in rocks to chemically bind with and store CO2 as a solid. All carbon removal has plusses and minuses. Reforestation, for example, is a relatively low-cost strategy offering benefits to communities, but may be subject to wildfires increasing the possibility of r further warming. It can also displace croplands, increasing risks to food security.

- Climate finance for both mitigation and adaptation must increase dramatically this decade.Public and private finance supporting fossil fuels far exceed funds directed towards climate mitigation and adaptation. While climate finance has increased 60% since 2014, it will need to increase between 3 and 6 times by 2030 to achieve mitigation alone. Funding needs to increase most for hard-pressed developing countries: sixfold for Southeast Asia and developing Pacific nations, fivefold for Africa and fourteenfold in the Middle East. This is needed by 2030 just to hold warming to 2oC. Finance for adaptation, and loss and damage, also needs to rise dramatically. Developing countries need US$127bn per year by 2030 and US$295bn per year by 2050. Current funding for adaptation falls well short of what is needed, being estimated as totalling less than US$50bn per year.

- Climate change and collective efforts to adapt to and mitigate it will exacerbate inequality unless a just transition is ensured. Households with income in the top 10%, largely in developed countries, emit around 45% of the world’s GHGs, while families in the bottom 50% of income emit up to 15%. Yet the effects of climate change most impact the poorer and more marginalised communities. Climate change mitigations can exacerbate inequality, e.g. retiring coal-fired power stations can displace workers; halting deforestation can heighten poverty and intensify food insecurity.

Summary of the 10 points from the IPCC Synthesis report has been adapted from O’Donnell (2023). CC BY-NC 4.0

Sociology and Climate Change

Climate change is therefore a sociological concern. The primary driver behind global climate change is socio-structural in nature. Its issues are embedded within institutions, cultural beliefs, values, and social practices. Dunlap and Brulle (2015) note that sociology brings two distinct and advantageous approaches to climate change research by examining its social dimensions. First, they contend sociology is equipped with the tools to examine and provide insight into the causes, consequences, and solutions attached to climate change. Efforts to ameliorate or adapt to its impacts require a deeper understanding of the social dynamics at different levels of analysis, from the global to the micro. Second, critical sociology provides a form of social critique by examining and questioning the dominant ideologies that reinforce current socioeconomic institutions and practices affecting the global environment. Showing how such hegemonic notions sustain particular interests provides insight into how dominant players are able to restrict policy options. Climate change cannot simply be rectified by technical fixes but must be addressed in concert with other influences on human behavior such as social, political, and economic structures.

Environmental sociology can be applied in three areas to provide a framework for future research and policy: (a) examining the causes and impacts of climate change; (b) exploring equitable mitigation, adaptation and just transition strategies; (c) investigating the socio-political dynamics of environmental advocacy, social movement mobilization, public opinion and climate change denial.

Causes and Impacts of Climate Change

Climate change is affected by anthropogenic factors where increases in greenhouse gases (GHG) are largely produced by human activities. Pressures on the environment such as GHG emissions and various other environmental pressures can be simplistically traced back to two principal driving forces: population and consumption.

Two dominant types of sociological explanation of these processes include the treadmill of production theory (Schnaiberg, 1980; Buttel., 1994) and ecological modernization theory (Islam, 2013; Mol, 1995; Goldman, 2002). Proponents of the treadmill of production theory have argued that the capitalist system has prioritized economic growth over social inequality and environmental protection, whereas advocates of ecological modernization theory have asserted that as society modernizes, the ecological rationality underpinning the need to protect the environment from the strains of human development will present itself. The latter may seem to be supported by the reduction in environmental harm and GHG emissions in developed nations. However, deeper assessment has revealed that the more developed nations have been able to export the effects of their environmental problems to less developed nations, supporting the former.

Two Types of Sociological Explanation for Climate Change

Treadmill of Production Theory

- The carrying capacity of the planet is finite.

- Industrialism and development cause ecological and environmental damage.

- Rates of resource extraction is unsustainable.

Ecological Modernization Theory

- Modernization can evolve to find sustainable solutions.

- Possible to increase the productivity of resources.

- Societies will be able to develop while the environment remains viable for the future.

This highlights the global context of climate change responses: the enduring global division of labour in which the developed or “core” nations have historically engaged in unequal exchanges of labour and natural resources with the poorer “peripheral” nations. Dealing with climate change is caught up in the underlying power dynamics and self-interest inherent in international relations. Less developed nations have feared international restraints on their efforts to grow economically to meet their own needs, while the more powerful developed nations, which are responsible for 60% of GHG emissions, have refused to curtail their own emissions. Accordingly, the less developed nations have become less willing to make sacrifices on behalf of the environment (Roberts and Parks, 2006).

An examination of the macroeconomic forces that have driven global climate change would not be complete without recognizing that at a micro-level individuals and household consumption have been major contributors to carbon and GHG emissions. It has been easy to overlook the impacts of micro consumption behavior as being a causal influence on environmental strain when blame could so readily be placed on large industries. However, sociologists have widely agreed on the large effect of growing affluence on carbon emissions through the consumption of food, water, goods, and services, through either the direct or indirect use of energy (Dietz et al., 2009; EPA, 2019; Gardner et al., 2008). Consumption patterns have had direct and indirect impacts on climate change and create a perception of climate injustice, especially when they have been driven by the desire for social status, conspicuous consumption, and leisure that secure one’s position in society (Bell, 2004; Veblen, 1994).

Making Connections: Sociology in the Real World

Monster Trucks and Petro-Masculinity

be flooded with excess gas, producing thick plumes of black smoke (Dagget, 2018). (Image courtesy of Salvatore Arnone/Wikimedia Commons.) CC BY 3.0

Canada uses more energy per capita than almost any other country in the world (Natural Resources Canada, 2016). One of the factors contributing to this situation is the heavy dependence on gasoline-powered vehicles. The contribution of private vehicle ownership to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions is a significant example of the role of micro-level, household consumption on climate change.

This is a self-perpetuating system referred to as automobility, a term that covers the full breadth of actors, materials, technologies, policies and practices that make up and reinforce private vehicle usage (Sovacool and Axsen, 2018).

Canadians possess approximately 19 million light-duty vehicles, (cars, vans, and light-duty trucks). They typically drive over 300 billion kilometers per year. Consequently, the transportation sector accounts for 27% of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in Canada. Within that sector, light-duty vehicles, including cars, vans, and light-duty trucks, contribute to almost half of the total emissions. With nearly one vehicle for every two Canadians, Canada claims one of the highest car ownership rates globally.

One of the troubling trends in automobility is the growth in purchase of monster trucks. Ford’s launch of its four-door F-150 pickup truck in the late 1990s allowed families to replace sedans and minivans with vehicles that seemed to have more utility, but it started the trend towards larger, more aggressively styled trucks with 4 door cabs, massive front ends and smaller beds. The dominance of “light” trucks in Canada’s new vehicle sales has increased significantly, with these vehicles representing almost 75% of the total (Bubbers, 2019). Since 1990, the average weight of pickups has increased by 1,256 lbs or 32% (Davis and Boundy, 2020). In 2019, there were 25 models of vans, trucks and SUVs that weighed at least 5,500 pounds, approximately double the weight of a Honda Civic.

Despite the advancements in engine fuel efficiency, the overall emissions from light-duty trucks, including pickups, SUVs, and vans, have more than doubled in Canada since 1990. This increase is primarily due to the sheer increase in the number of light trucks on the roads.

There is a certain irrationality to buying monster trucks, especially given people’s awareness of climate change. The majority of truck owners live in cities where trucks are used for local commutes rather than hauling bales of hay, towing trailers or off-roading. Many consumers choose big trucks because they make them feel safer and less vulnerable on the road, which is ironic because pickups and SUVs account for about a quarter of all collisions with pedestrians and bikes, but nearly half of all the deaths (Edwards and Leonard, 2022).

But the size and styling of trucks is also part of North American truck culture in which trucks serve as important signifiers of race, class and gender identity. Dagget (2018) describes the formation of petro-masculinity as an exaggerated expression of masculinity tied to a backlash against climate change discourse. This manifests as a malicious pride in the burning of fossil fuels, the desire for ever larger and more “aggressive” trucks, climate denial, and even truck-centric “Freedom Convoy” style protests against measures to reduce emissions. In all of this, beleaguered masculine identity is the core component of reaction. It is a species of politicized hypermasculinity which “arises when agents of hegemonic masculinity feel threatened or undermined, thereby needing to inflate, exaggerate, or otherwise distort their traditional masculinity” (Agathangelou and Ling, 2004).

For much of the 20th and 21st centuries the privileges and affluence of the North American way of life was centred around intensive fossil fuel consumption and jobs (mostly white and male) reliant upon fossil fuel systems. While “the planet is telling us that there are limits to human freedom; there are freedoms and political choices we can no longer have” (Burke et al., 2016). Extracting and burning fuel has been a core component of white, male breadwinner/provider identity. As irrational as it may be, fossil fuels and monster trucks become potent symbols that represent autonomy, self-sufficiency, and a nostalgia for unconstrained male power. As Dagget (2018) says, “it is no coincidence that white, conservative American men — regardless of class — appear to be among the most vociferous climate deniers, as well as leading fossil fuel proponents in the West.”

The concept of petro-masculinity suggests that fossil fuel use is not driven simply by corporate interests and strategies of capital accumulation. The ecological modernization theory that renewable energy solutions will simply displace fossil fuels as cost, efficiency, and capacity improve neglects the way fossil fuel politics secure cultural meaning and political identities. Fossil fuel use is also driven by powerful forces of nostalgia, desire, anxiety, and beleagured masculine identity, which poses problems for finding consensus on post-carbon energy solutions.

When petro-masculinity is at stake, climate denial is thus best understood through desire, rather than as a failure of scientific communication or reason. In other words, an attachment to the righteousness of fossil fuel lifestyles, and to all the hierarchies that depend upon fossil fuel, produces a desire to not just deny, but to refuse climate change. Refusing climate change is distinct from ignoring climate change, which is effectively what many people who otherwise acknowledge its reality do…. It demands struggle. In the case of climate change, by refusing it, one also subscribes to an accelerated investment in petrocultures (Dagget, 2018).

Recently, policies to lower carbon emissions have pushed automakers to redesign their vehicles from fuel to battery power. As a result, monster trucks have also begun to be redesigned as full EV (Electric Vehicle) models. People can have their monster trucks with half the lifetime emissions of comparable gas-powered model (Vermes, 2023). However, it is not clear effect petrol-masculinity will have on their acceptance in the market place.

Equitable Mitigation and Environmental Racism

A second emphasis of environmental sociology is environmental inequality and the related concept of environmental racism. Environmental inequality (also called environmental injustice) refers to the fact that low-income and marginalized people are disproportionately likely to experience various environmental problems, while environmental racism refers to the greater likelihood that racialized people experience these problems (Walker, 2012). With regard to climate change, the analysis of environmental inequity proceeds from three underlying assumptions. First, social inequalities have driven overconsumption. Second, the impacts of climate change have been experienced unequally by the rich and poor, which may extend to future generations. Third, policies that have been designed to deal with climate change have had unequal consequences for the unrepresented and the poor (Harlan et al., 2016).

Harlan et al. (2016) argue that to attain a level of understanding on climate disruption, researchers and policymakers must be sensitive to the inequalities of wealth, power, and privilege. The notion of inequality has to be extended to the rich–poor dichotomy not only within but also between nations. Within nations, toxic and polluting industries have been located in the poorer districts, because properties in such locations have been considered less valuable (Roberts and Toffolon-Weiss, 2001). Almost all hazardous waste sites are located in or near neighborhoods and communities that are largely populated by low-income and racialized people. Likewise, between core and peripheral societies, ecologically unequal exchanges occur due to resource plundering and pollution from the side effects of transnational industrial operations (e.g., tailings ponds, oil spills, mercury poisoning, etc.) (Jorgenson et al., 2011; Pellow, 2009).

Adaptation to climate change requires mitigating its effects, such as the intensity and frequency of extreme weather, the consequences of temperature variations, or the impacts on food security, livelihoods, and human health. Some communities are more vulnerable than others, and in particular there are people who are socially isolated due to their limited ability to cope with environmental stressors. However, the response to vulnerability “includes not only how climate change contributes to vulnerability, but also how climate change policy and response measures may magnify the effects of many existing drivers of vulnerability” (Mearns and Norton, 2009). In the short term, the largest impact on the disadvantaged and vulnerable has resulted less from climate change and more from the adverse consequences of climate change policy such as decreased access to affordable energy for the poor.

As climate impacts have been experienced differently across populations, enhancing the adaptive capacities of the most afflicted should offer a way to rethink policy with justice as its focus. It is not effective to try to deal with environmental issues without addressing the problem of inequality. This matters for three principal reasons: (a) there has been inequality in suffering, with the poor and vulnerable populations suffering more; (b) the poorer and less developed nations have had less bargaining power than the richer and more developed nations; and (c) the lessons from the failures of the Kyoto Protocol and the Copenhagen Accord have shown that an effective climate agreement cannot be achieved without addressing global inequality (Islam, 2013; Roberts, 2009).

Social Movements and Change

Climate change is a deeply controversial subject, despite decades of scientific research and a high degree of scientific consensus that supports its existence. Out of a data set of 88125 climate-related papers published since 2012, Lynas et al (2021) found 99% consensus that contemporary climate change is human-caused. Why is climate change a controversy? Sociological studies have highlighted how social movements play a critical role in creating consensus on addressing climate change through citizen mobilization but given the contemporary political climate this can go either way.

Climate change has been a major political issue across the globe and environmental movements to address climate change at the international and national levels have been seen as a critical component of social change (Cagnigla, 2015). Environmental social movements have been effective in changing policy through three actions: policy advocacy, policy research, and opening space for political reforms (IPCC, 2018). Movements have changed the social landscape in a basic way by framing grievances in a resonating manner: providing definitions of problems, directing blame and responsibility, and examining the options for solving the problems raised. The contrast between the pioneering findings from Gallup’s 1992 Health of the Planet Survey, which examined concerns over the environment across richer and poorer nations (Dunlap et al., 1993), and the World Values Survey, which examined individual-level postmaterialist/ materialist values (Dorsch, 2014) against recent polls (such as Gallup, 2010; World Value Survey, 2021; Kvaløy et al., 2012) has shown indications of an increasing trend toward greater awareness and understanding of climate change. This understanding has included greater concerns over climate change and general support for policies that have addressed the associated problems.

On the other hand, counter-movements against measures to address climate change like carbon pricing and regulating polluters have their roots in the anthropocentric view of the natural world: the idea that the natural world was created for human use. It is no coincidence that mobilization against climate change has emerged to deny the existence of the underpinning problems associated with it. Conservative movements and those with industrial neoliberal agendas have largely been blocking climate change policymaking. One key strategy is to manufacture uncertainty about climate science and undermine scientific reports by highlighting the inadequacy of evidence and contesting methodologies and analyses (Michels et al., 2005; Oreskes et al., 2010). Dunlap and McCright (2015) describe the idea of contrarian scientists who have the explicit goal of generating uncertainty by exploiting the complexities of scientific investigation. The challenges from contrarian scientists have had two aims: (1) to undermine the validity and legitimacy of climate change and (2) to attack the authority and integrity of individuals or other groups of scientists.

Recent environmental sociology has called for a new ecological paradigm (Catton and Dunlap, 1978; 1980). It developed as a shift away from the “human exemptionalism paradigm” (HEP) and the notion of a neoliberal growth imperative, both of which assumed that human societies have the ability to transcend biophysical limits and have the capacity for ever-increasing economic expansion. The association between economic growth and human development has been unsustainable over the long run. The new ecological paradigm considers society’s embeddedness in nature. Kais and Islam (2018) note that the role of environmental sociology is to direct attention and sensitize policymakers to the biophysical impacts and limits of human development.

Taken as whole, the complex problem of climate change cannot be understood and addressed without uncovering its deep nexus with the socio-political issues in our societies. Herein lies the critical and crucial contributions of sociology and other social science disciplines.

Making Connections: Social Policy and Debate

Deep Ecology and the Concept of Appropriate Technology

Of the various environmentalist movements that emerged from the 1960s on, deep ecology is the movement that wrestled most directly with the idea that the natural word is not simply a resource to be exploited by human beings. In deep ecology, the eco-system and members of the natural world are not resources to be used because “all beings have intrinsic value” (Drengson, 1983). All beings are equally important members of a biospheric community (Naess, 1995). From the deep ecology perspective, living with nature requires a thorough political reorientation of human societies based on a whole ecosystem approach to re-evaluating and redesigning human activity.

In the development of the environmental movement, deep ecologists made a distinction between “shallow,” reformist ecology and a more radical “deep” ecology (Drengson, 1983). Shallow ecology is based on the idea of sustainable, but nevertheless anthropocentric or human-oriented, use of natural resources. Efforts to reduce carbon pollution, maintain habitat diversity, preserve wilderness, address pollution and air quality and so on are still focused on sustaining the survival, priorities and needs of humans. Deep ecology is based on a non-anthropocentric, “eco-spheric egalitarianism” in which all members of the eco-system have equal and intrinsic value. As Naess and Sessions (1995 [1984]) put it, “the well-being and flourishing of human and nonhuman Life on Earth have value in themselves (synonyms: intrinsic value, inherent value). These values are independent of the usefulness of the nonhuman world for human purposes.”

This raises the central practical question of environmental movements: how can humans live in harmony with nature? The poet and deep ecologist Gary Snyder (1990) conceptualizes the practice of ecological harmony as a practice of re-inhabitation: relearning what it means to live in a place or deepening the experience and awareness of one’s home place. This means first of all to recognize that wherever one lives, one’s habitat is defined by an ecosystem and its natural parameters. A bioregion is defined as a geographical area that is determined not by political or administrative boundaries but by ecological systems, such as a watershed, a river estuary, a coastal environment, a mountain range or plain. For Snyder, this leads to specific way of life or ethic of bioregional stewardship — “find your place on the planet, dig in, and take responsibility from there” (Snyder, 1995).

Another outcome of deep ecology has been to propose a set of principles of environmental design and appropriate technology. As discussed throughout this chapter, many of the most serious problems confronting life in the 21st century are the products of capitalist accumulation practices and industrial scientific-technological developments that are in principle indifferent to the ecological systems in which they are embedded. As technology practices have an impact on everyday life, society, and on the ecosystem, an appropriate technology is defined as one that is especially suited and fit to its ecological and social context (Drengson, 1995). Criteria of appropriateness include technologies that are:

- Ecologically sound

- Equitable and sustainable

- Decentralized/human scaled

- Developed to solve genuine problems of human need

- Designed to facilitate the progress of human and other species’ development: increasing the quality of life and possibilities of self-realization (Drengson, 1995).

Gary Snyder sums up the problem of ecological harmonization through the relation to “the wild” or wilderness in modern civilization. “Thoreau says ‘give me a wildness no civilization can endure.’ That’s clearly not difficult to find. It is harder to imagine a civilization that wildness can endure, yet this is just what we must try to do” (Snyder, 1990).

Media Attributions

- Figure 20.24 NEkenyaFB27 by Colin Crowley, via Flickr, is used under a CC BY 2.0 licence.

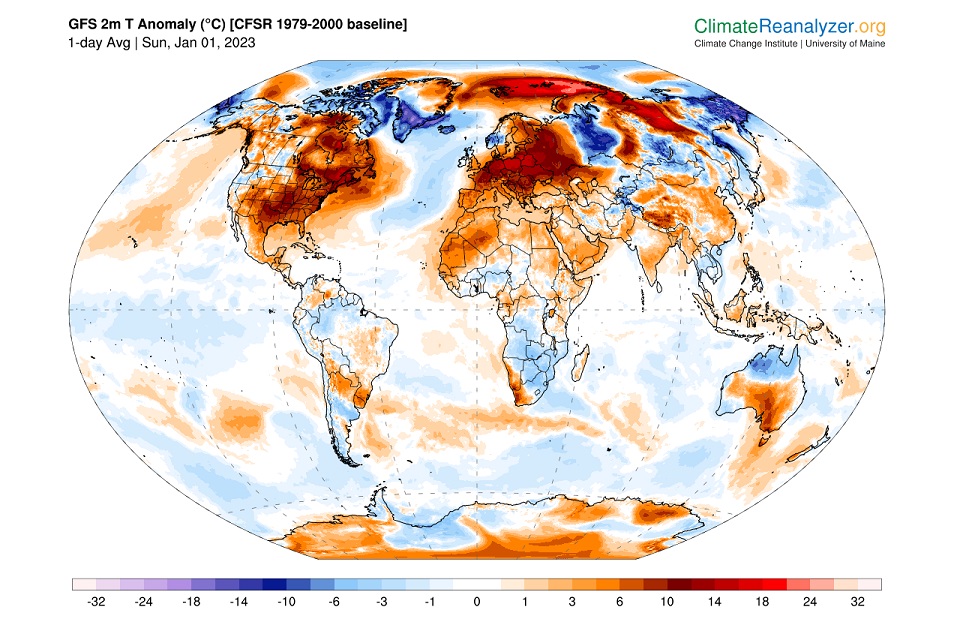

- Figure 20.25 GFS Tm T Temperature Anomaly (Jan 1, 2023) from ClimateReanalyzer.org is used under a CC BY-NC 4.0 licence.

- Figure 20.26 F-450 coal rolling Monster by Salvatore Arnone, via Wikimedia Commons, is used under a CC BY 3.0 licence.

- Figure 20.27 Picture of Dryden Mill by Shane Trist, via Wikimedia Commons, is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 licence.

- Figure 20.28 Alan Drengson. Image used with permission.