3.3. Culture as Innovation: Pop Culture, Subculture, Global Culture

In the introduction to this chapter, culture was defined as the source of the shared meanings through which people interpret and orient themselves to the world. While cultural practices are in some respects always a response to biological givens or to the structure of the socioeconomic formation, they are not determined by these factors. Culture is innovative. It expresses the human imagination in its capacity to go beyond what is given, to solve problems, to produce innovations — new objects, ideas, or ways of being introduced to culture for the first time. At the same time, people are born into cultures that pre-exist them and shape them. Languages, ways of thinking, ways of doing things, and artifacts are elements of culture people do not invent but inherit. They are ready-made forms of life that people fit themselves into. Culture can, therefore, also be restrictive, imposing ways of life, beliefs, and practices on people, and limiting the possibilities of what they can think and do. As Karl Marx (1852) said, “the tradition of all dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living.”

The next two sections of this chapter will examine aspects of culture which are innovative — high culture and popular culture, subcultures, and global culture — and aspects of culture which are restrictive — rationalization and consumerism.

High Culture and Popular Culture

Does a person prefer listening to opera or hip hop music? Do they like watching horse jumping or NASCAR? Do they read books of poetry or magazines about celebrities? In each of these choices, one type of entertainment is considered high culture and the other low culture. Sociologists use the term high culture to describe forms of cultural experience that are meant to cultivate and refine people’s sensibility: their ability to appreciate and respond to complex emotional, intellectual, or aesthetic influences. High cultural forms are characterized by formal complexity, eternal values, originality, and authenticity such as is provided by Beethoven’s string quartets, Picasso’s paintings, Sergei Diaghilev’s ballets, or James Joyce’s Ulysses. People often associate high culture with intellectualism, aesthetic taste, elitism, wealth, and prestige because it is not immediately accessible and requires cultivation or education to appreciate.

Pierre Bourdieu (1984) argues further that high culture is not only a symbol of cultural distinction, but a means of maintaining status and power distinctions through the transfer of cultural capital: the knowledge, skills, tastes, mannerisms, speaking style, posture, material possessions, credentials, etc. that a person acquires from their family and class background. Events considered high culture can be expensive and formal — attending a ballet, seeing a play, or listening to a live symphony performance — and the people who are in a position to appreciate these events are often those who have enjoyed the benefits of an enriched and exclusive educational background. Their sophistication is the product of an investment in cultural refinement that serves as the basis of status distinctions in society. Nevertheless, high culture itself is a product of focused and intensive cultural innovation and creativity.

The term popular culture refers to forms of cultural experience and attitude that circulate in mainstream society: cultural experiences that are well-liked by “the people.” Popular culture events might include folk music, hip hop, parades, hockey games, or rock concerts. Some popular culture originated in folk traditions like quilting, carnival festivities, fiddle music, spirit dancing, commedia dell’arte and religious festivals. Other pop culture is considered popular because it is commercialized and marketed to a wide audience. Rock and pop music — “pop” is short for “popular” — are part of modern popular culture that developed first with the publication of sheet music and then with recordings. In modern times, popular culture is often expressed and spread via commercial media such as radio, television, movies, the music industry, bestseller publishers, and corporate-run websites. Unlike high culture, popular culture is known and accessible to most people. One can expect to be able to share a discussion of favourite hockey teams with a new coworker, or comment on a current TV show when making small talk in the check-out line at the grocery store. But if you tried to launch into a deep discussion on the classical Greek play Antigone, few members of Canadian society today would be familiar with it.

Although high culture may be viewed as artistically superior to popular culture, the labels of high culture and popular culture vary over time and place. Shakespearean plays, considered pop culture when they were written, are now among Canadian society’s high culture. In the current “Second Golden Age of Television” (2000s to the present, the first Golden Age was in the 1950s and 1960s), television programming has gone from mass audience situation comedies, soap operas, and crime dramas to the development of “high-quality” series with increasingly sophisticated characters, narratives, and themes that require full attention and cultural capital to follow (e.g., The Sopranos, Breaking Bad, Game of Thrones, The Crown).

Contemporary popular culture is frequently referred to as a postmodern culture. This is often presented in contrast to modern culture, or modernity. The term modernity refers to the culture associated with the rise of capitalism in which the world came to be experienced as a place of constant change and transformation, and culture as a sequence of new or contemporary “nows” in which the things of today are “modern” and those of yesterday old and no longer relevant (Sayer, 1991).

In the era of modern culture, or modernity, the distinction between high culture and popular culture framed the experience of culture in a more or less a clear way. One side of high culture in the 19th and 20th century was experimental and avant-garde, seeking new and original forms in literature, art, and music to authentically express the elusive, transient, ever-changing experiences of modern life. The other side of high culture was the tradition of conserving and passing down the highest and most refined expressions of human cultural possibility: the eternal values and noble sensibilities contained in the “great works” of culture. High culture had a civilizing mission to either capture and articulate new forms of experiencing the world, or to preserve, pass down and renew what was eternal in the tradition. In both forms, high culture appealed to a limited but sophisticated audience.

Popular culture, on the other hand, was simply the culture of the people; it was immediately accessible and easily digestible, either in the form of folk traditions or commercialized mass culture. It had no pretension to be more than entertainment and the site of momentary enthusiasms and fads — hit songs, bestsellers, popular film stars, fashion trends, house decor styles, dance crazes, etc.

In postmodern culture — the form of culture that comes after or ‘post’ modern culture — this distinction begins to break down, and it becomes more common to find various sorts of mash-ups of high and low: Serious literature combined with themes from zombie movies; pop music constructed from recycled samples of original hooks and melodies; symphony orchestras performing the soundtracks of cartoons; architecture that playfully borrows and blends historical styles instead of inventing new ones; etc. Rock music is now the subject of many high brow histories and academic analyses, just as the common objects of popular culture are transformed into symbols with depth of meaning as high art (e.g., Andy Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup Cans or Marvel Studios epics based on kid’s comic books of the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s). The dominant sensibility of postmodern popular culture is both playful and ironic, as if the blending and mixing of cultural sources, like in the television show The Simpsons, is one big in-joke based on references that only people ‘in the know’ will get. Postmodern culture has therefore been referred to as a “culture of quotations” (Jameson, 1985) in the sense that instead of searching for new, authentic forms, as in avant-garde modernism, or preserving and revering high cultural sensibilities, as in the classics, it recycles and remixes (i.e., quotes) elements of previous cultural production, often with a tongue in cheek ironic attitude.

Frederic Jameson (1985) argues that the mixing and blending of postmodern culture is not just a cultural trend or fashion, but reflects an underlying shift in the nature of culture itself. From a historical materialist perspective, if the culture of modernity was tied to the rise of industrial capitalism, the culture of postmodernity is tied to late capitalism. The culture of modernity was focused on the new, just as capitalism has to constantly innovate in the pursuit of markets and profitability. But the categories of high and low remained stable, just as the commodities of industrial capitalism remained concrete: resources, appliances, automobiles, etc. However, late capitalism is much less concrete. The commodities of late capitalism are frequently images, brands, services and knowledge rather than tangible industrial products. The dominant technologies are computer codes and instantaneous communication networks rather than railroads and industrial machinery. Flows of capital investment are globalized rather than centered in particular national economies and cultures. Jameson argues that under these circumstances it becomes increasingly difficult to “cognitively map” ones location in this complex global space, although this is what a culture is suppose to do.

The outcome is the emergence of a postmodern culture, which is seen to challenge modern culture in a number of key ways. The postmodern eclectic mix of elements from different times and places challenges the modernist concepts of authentic expression and progress. The idea that cultural creations can and should seek new and innovative ways to express the truths and deep meanings of life was linked to a belief in social progress. The playfulness and irony of postmodern culture seem to undermine the core values of modernity, especially the idea that cultural critique or innovations in architecture, art, and literature, etc. have an important role in, not just entertaining people, but improving the quality of social life. In postmodernity, nothing is to be taken very seriously, even people themselves. Moreover, in postmodernity everyone with access to a computer and some editing software is seen to be a cultural producer; everyone has a voice and with enough “likes” any voice can be important and influential. Access to knowledge does not require arduous and careful research but is simply a matter of crowd-sourcing. The modernist myth of the great creator or genius is rejected in favour of populism and a plurality of voices.

Jean Francois Lyotard (1984) defines postmodern culture as “incredulity towards metanarratives” meaning that postmoderns no longer really believe in the big (i.e., meta) stories and social projects of modernity: progress towards universalization, rationalization, and systemization. Postmoderns are skeptical of the claims that scientific knowledge leads to progress, that political change creates human emancipation, that Truth sets people free.

Some argue pessimistically that the outcome of this erosion of authority and decline in consensus around core values is a thorough relativism of values in which no standard exists to judge one thing to be more significant than another. Everyone makes up their own little stories, each as valid as the next — as sociologists have observed with regard to conspiracy theories, or people “doing their own research” on the science of climate change or vaccines. The outcome of the postmodern condition is a culture without a consensus on common, shared standards of truth, value or even a shared reality.

Others argue optimistically that the outcome leads to pluralization, an emancipation from centralized institutions of authority, and a weakening of attachments to the dominant culture. It brings a loosening of social bonds and increased freedom. Postmodernism enables a necessary critique of the unexamined assumptions of power and authority in modern culture — the rhetoric of patriotism, “family values,” or “scientific progress” lampooned in The Simpsons, for example. Instead of the privileged truths of elites and authorities, postmodernity witnesses the emergence of a plurality of different voices that had been relegated to the margins. Culture moves away from homogeneous sameness and uniformity to heterogeneous diversity.

Subculture and Counterculture

A subculture is just as it sounds — a smaller cultural group within a larger parent culture. People of a subculture are part of the parent culture, but also share a specific identity within a smaller group that distinguishes them. Many subcultures exist within Canada. Within larger ethnic groups, who share the language, food, and customs of their heritage, are subcultures like Rastafarianism, Bhangra, or Chadō. Other subcultures are united by shared pastimes. For example, biker culture revolves around a dedication to motorcycles. Some subcultures are formed by members who possess traits or preferences that differ from the majority of a society’s population. The body modification community embraces aesthetic additions to the human body, such as tattoos, piercings, and certain forms of plastic surgery. But even as members of a subculture band together around a distinct identity, they still identify with and hold many things in common with their larger parent culture.

As Hall, Jefferson and Roberts (1975) point out with respect to bohemian subculture for example:

The bohemian sub-culture of the avant-garde which has arisen from time to time in the modern city, is both distinct from its ‘parent’ culture (the urban culture of the middle class intelligentsia) and yet also a part of it (sharing with it a modernising outlook, standards of education, a privileged position vis-a-vis productive labour, and so on).

Sociologists distinguish subcultures from countercultures, which are a type of subculture that explicitly reject the larger culture’s norms and values. In contrast to subcultures, which operate relatively smoothly within the larger society, countercultures actively defy larger society by developing their own set of rules and norms to live by, sometimes even creating alternative communities that operate outside of the greater society. Vegans who choose to not eat meat, fish or dairy products because they like the health benefits, cuisine or lifestyle of the vegan diet would be an example of a subculture. Although this dietary choice is distinct from the dominant culture, dietary health, pleasure in good food and making lifestyle choices are consistent with dominant cultural values. However, vegans who reject the industrial food system and the harvesting of animals for human consumption entirely have to take more radical steps to build a life which is consistant in itself and outside or counter to the dominant norms and structures of society.

The post-World War II period was characterized by a series of “spectacular” youth cultures — teddy boys, beatniks, mods, hippies, bikers, skinheads, Rastas, punks, new wavers, ravers, hip-hoppers, and hipsters — who in various ways sought to reject the values of their parents’ generation. For some, joining these groups was just for the music, clothing or style of life. But for others, the rejection of the dominant culture had more radical implications. The hippies, for example, were a subculture that became a counterculture, blending protest against the Vietnam War, industrial technology, and consumer culture with a back to the land movement, non-Western forms of spirituality, and the practice of voluntary simplicity. They “explored ‘alternative institutions’ to the central institutions of the dominant culture: new patterns of living, of family-life, of work or even ‘un-careers’” (Hall, Jefferson and Roberts, 1975). Counterculture, in this example, refers to the culture or way of life taken by a political and social protest movement.

Cults, a word derived from cultus or the “care” owed to the observance of spiritual rituals, are also considered countercultural groups. They are usually informal, transient, religious groups or movements that deviate from orthodox beliefs and often, but not always, involve an intense emotional commitment to the group and allegiance to a charismatic leader. In pluralistic societies like Canada, they represent quasi-legitimate forms of social experimentation with alternate forms of religious practice, community, sexuality and gender relations, proselytizing, economic organization, healing, and therapy (Dawson and Thiessen, 2014). However, sometimes their challenge to conventional laws and norms is regarded as going too far by the dominant society. For example, the group Yearning for Zion (YFZ) in Eldorado, Texas existed outside the mainstream, and the limelight, until its leader was accused of statutory rape and underage marriage. The sect’s formal norms clashed too severely to be tolerated by U.S. law, and in 2008 authorities raided the compound, removing more than 200 women and children from the property (Oprah.com, 2009).

The degree to which countercultures reject the larger culture’s norms and values is questionable, however. In the analysis of spectacular, British working class youth subcultures like the teddy boys, mods, and skinheads, Phil Cohen (1972) noted that the style and the focal concerns of the groups could be seen as a “compromise solution between two contradictory needs: the need to create and express autonomy and difference from parents…and the need to maintain parental identifications” (as cited in Hebdige, 1979). In the 1960s and 70s, for example, skinheads shaved their heads, listened to ska music from Jamaica, participated in racist chants at soccer games, and wore highly polished Doctor Marten boots (“Doc Martens”) in a manner that deliberately alienated their working class parents while expressing their own adherence to blue collar working class imagery. At the same time, noted Cohen, their subcultural outfit was more or less a “caricature of the model worker” their parents aspired to, and their attitude simply exaggerated the proletarian, puritanical, and chauvinist traits of their parents’ generation. On one hand, the invention of skinhead culture was an innovative cultural creation that seemed to reject the dominant culture; on the other hand, it just exaggerated and reproduced the already existing contradictions of the skinheads’ class position and that of their parents.

Making Connections: Sociology in the Real World

The Evolution of North American Hipster Subculture

Skinny jeans, chunky glasses, ironic moustaches, retro-style single speed bicycles, and T-shirts with vintage logos — the hipster is a recognizable figure in contemporary North American culture. Predominantly based in metropolitan areas, hipsters seek to define themselves by a rejection of mainstream norms and fashion styles. As a subculture, hipsters spurn many values and beliefs of North American society, tending to prefer a bohemian lifestyle over one defined by the accumulation of power and wealth. At the same time they evince a concern that borders on a fetish with the pedigree of the music, styles, and objects that identify their focal concerns.

When did hipster subculture begin? While commonly viewed as a recent trend among middle-class youth, the history of the group stretches back to the early decades of the 1900s. In the 1940s, black American jazz music was on the rise in the United States. Musicians were known as hepcats and had a smooth, relaxed style that contrasted with more conservative and mainstream expressions of cultural taste. Norman Mailer (1923 – 2007), in his essay The White Negro: Superficial Reflections on the Hipster (1957), defined those who were “hep” or “hip” as largely white youth living by a black jazz-inspired code of resistance, while those who were “square” lived according to society’s rules and conventions.As hipster attitudes spread and young people were increasingly drawn to alternative music and fashion, attitudes and language derived from the culture of jazz were adopted. Unlike the vernacular of the day, hipster slang was purposefully ambiguous. When hipsters said, “It’s cool, man,” they meant not that everything was good, but that it was the way it was.

By the 1950s, another variation on the subculture was on the rise. The beat generation, a title coined by Quebecois-American writer Jack Kerouac (1922-1969), was defined as a generation that was nonconformist and anti-materialistic. Prominent in this movement were writers and poets who listened to jazz, studied Eastern religions, experimented with different states of experience, and embraced radical politics of personal liberation. They “bummed around,” hitchhiked the country, sought experience, and lived marginally. Even in the early stages of the development of the subculture there was a difference between the emphasis in beat and hipster styles:

. . . the hipster was . . . [a] typical lower-class dandy, dressed up like a pimp, affecting a very cool, cerebral tone — to distinguish him from the gross, impulsive types that surrounded him in the ghetto — and aspiring to the finer things in life, like very good “tea,” the finest of sounds — jazz or Afro-Cuban . . . [whereas] . . . the Beat was originally some earnest middle-class college boy like Kerouac, who was stifled by the cities and the culture he had inherited and who wanted to cut out for distant and exotic places, where he could live like the “people,” write, smoke and meditate (Goldman as cited in Hebdige, 1979)

While the beat was focused on inner experience, the hipster was focused on the external style.

By the end of the 1950s, the influence of jazz was winding down and many traits of hepcat culture were becoming mainstream. College students, questioning the relevance and vitality of the American dream in the face of post-war skepticism, clutched copies of Kerouac’s On the Road, dressed in berets, black turtlenecks, and black-rimmed glasses. Women wore black leotards and grew their hair long. The subculture became visible and was covered in Life magazine, Esquire, Playboy, and other mainstream media. Herb Caen (1916-1997), a San Francisco journalist, used the suffix from Sputnik 1, the Russian satellite that orbited Earth in 1957, to dub the movement’s followers as “beatniks.” They were subsequently lampooned as lazy layabouts in television shows like The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis (1959-1963) or dangerous, drug-abusing delinquents in movies like High School Confidential (1958).

As the beat generation faded, a new related movement began. It too focused on breaking social boundaries, but also advocated freedom of expression, philosophy, and love. It took its name from the generations before; in fact, some theorists claim that the beats themselves coined the term to describe their children. Over time, the “little hipsters” of the 1960s and 70s became known simply as hippies. Others note that hippie was a derogatory label invented by the mainstream press to discredit and stereotype the movement and its non-materialist aspirations.

Contemporary expressions of the hipster rose out of the hippie movement in the same way that hippies evolved from the beats and beats from hepcats. Although today’s hipster may not seem to have much in common with the jazz-inspired youth of the 1940s, or the long-haired, back-to-the-land movement of the 1960s, an emphasis on nonconformity persists. The sociologist Mark Greif set about investigating the hipster subculture of the United States and found that much of what tied the group together was not a specific set of fashion or music choices, nor a specific point of contention with the mainstream. What has emerged, rather, is an appropriation of consumer capitalism that seeks authenticity in and of itself. In his New York Times article “The Hipster in the Mirror” Greif wrote, “All hipsters play at being the inventors or first adopters of novelties: pride comes from knowing, and deciding, what’s cool in advance of the rest of the world” (2010). What tends to be cool is an ironic pastiche of borrowed styles or tastes that signify other identities or histories: alternative music (sometimes very obscure), used vintage clothing, organic and artisanal foods and products, single gear bikes, and countercultural values and lifestyles.

Young people are often drawn to oppose mainstream conventions. Much as the hepcats of the jazz era opposed common culture with carefully crafted appearances of coolness and relaxation, modern hipsters reject mainstream values with a purposeful apathy, while embracing their particular enthusiasms with what seems to others like excessive intensity and attention to detail. Ironic, cool to the point of non-caring, and intellectual, hipsters continue to embody a subculture while simultaneously impacting mainstream culture.

Global Culture

The integration of world markets, technological advances, global media communications, and international migration of the last decades have allowed for greater exchange between cultures through the processes of globalization and diffusion. As noted in Chapter 1. An Introduction to Sociology, globalization refers to the ways in which people no longer “live and act in the self-enclosed spaces of national states and their respective national societies” (Beck, 2000). Globalization is the process by which “a supraterritorial dimension of social relations” emerges and spreads (Scholte, 2000). The world is becoming one place, like a “global village,” as Canadian media theorist, Marshall McLuhan (1962) described. In this context, culture itself has become increasingly globalized. Life styles, activities, cuisines, clothing styles, cultural references, religions, music preferences, images, news reports and many other facets of contemporary cultural life are no longer pinned to the location where people live or grew up.

Globalization has been a process underway for 500 years but it has intensified over the last 30 years. Arjun Appadurai (1996) describes five dimensions of global cultural “flow” that have reshaped the landscape of culture in the 21st century.

- First is the increased movement or flow of people who bring their local cultures with them. He refers to this process as the creation of a new global ethnoscape: “tourists, immigrants, refugees, exiles, guest workers, and other moving groups and individuals constitute an essential feature of the world and appear to affect the politics of (and between) nations to a hitherto unprecedented degree.”

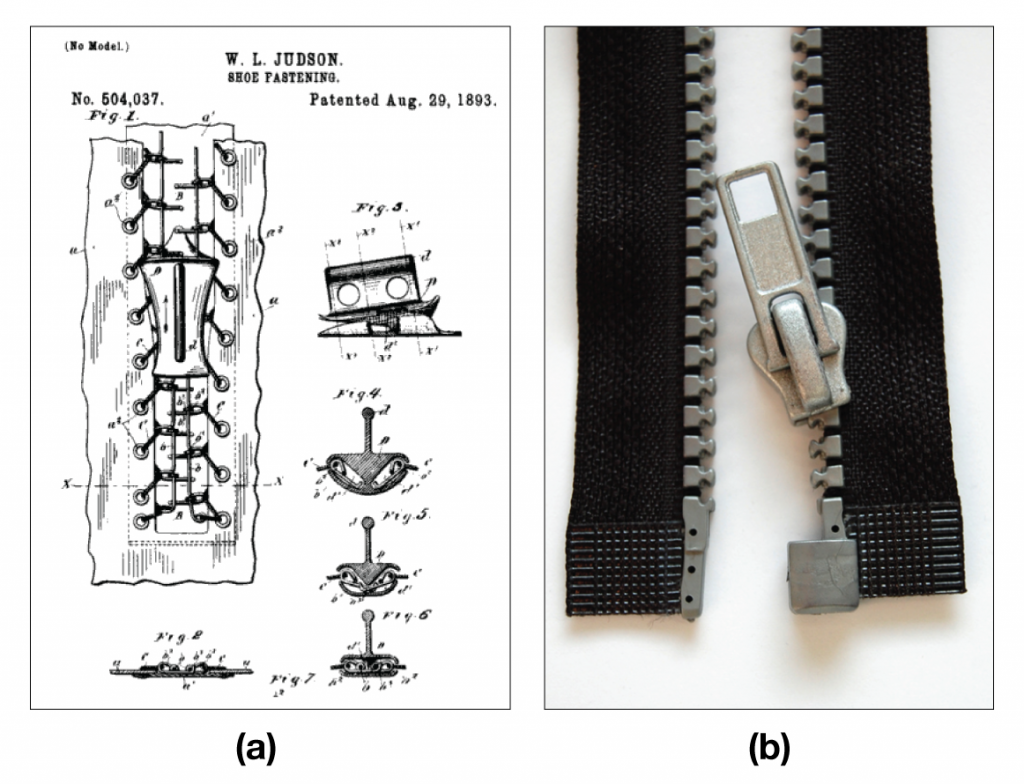

- Second is the spread of technologies across borders, from electric toothbrushes and automobile parts to smart phones and biotech, which creates a global technological configuration or technoscape. Among other things, the global spread of technologies requires an immense amount of global cooperation to define the 22,000 international standards that allow technical components to work together (Frost, 2018).

- Third is the creation of new financescapes. Beginning in the 1970s, Western governments began to deregulate social services while granting greater liberties to private businesses. As a result of this process of neoliberalization, world markets became dominated by unregulated, international flows of capital investment and new multinational networks of corporations. A global economy emerged to surpass nationally-based economies.

- Finally Appadurai describes the new mediascapes and ideoscapes that emerge as people consume media content and political or religious discourses from different locations through global film and TV distribution, social media platforms like Google, Facebook and Twitter, and other electronic means of news and personal communication. These create “large and complex repertoires of images, narratives, and ethnoscapes to viewers throughout the world, in which the world of commodities and the world of news and politics are profoundly mixed” (Appadurai, 1996). The world shares a common information (and disinformation) space.

These processes of cultural globalization can be summed up by the term diffusion, which refers to the spread of material and non-material culture. Middle-class North Americans can fly overseas and return with a new appreciation of Thai noodles or Italian gelato. Access to television and the internet has brought the lifestyles and values portrayed in Hollywood sitcoms and “reality” TV series into homes around the globe. Twitter feeds from public demonstrations in one nation have encouraged political protesters in other countries. When this kind of diffusion occurs, material objects and ideas from one culture are introduced into another creating new and complex landscapes of cultural diversity.

Diaspora and Hybridity

One aspect of this complex landscape of cultural diversity is the creation of diasporas. The increasing flows of global migrants, temporary foreign workers, and political or economic refugees create globalized and displaced local communities as people from around the world spread out into global diasporas: the communities that emerge through resettlement of a people from their original homeland to new locations. As Arjun Appadurai (1996) suggests, “More people than ever before seem to imagine routinely the possibility that they or their children will live and work in places other than where they were born: this is the wellspring of the increased rates of migration at every level of social, national, and global life.” This likelihood of movement, whether actual or imagined, changes the cultural coordinates of how people see themselves in the world.

All migrants, refugees, temporary foreign workers, or travelers bring their beliefs, attitudes, languages, cuisines, music, religious practices, and other elements of local ways of life with them when they move, and they encounter new ones in the places where they arrive. What would appear to be different in the contemporary era of global migration is the way in which electronic media make it possible for migrants and travelers to keep in touch daily with not only friends and family, but also favourite TV shows, current events, sports, music, and other elements of culture from home. In the same way, electronic media give migrants access to the culture of their new homes just as they allow local residents to imagine future homes elsewhere in the world. In the era of globalization, the experience of culture is increasingly disembedded from location. The ways people imagine themselves and define their individual attachments, interests, and aspirations criss-cross and intertwine the divisions between cultures formerly established by the territorial boundaries of societies.

Hybridity in cultures is one of the consequences of the increased global flows of capital, people, culture, and entertainment. Hybrid cultures refer to new forms of culture that arise from cross-cultural exchange, especially in the aftermath of the colonial era. On one hand, there are blendings of different cultural elements that had at one time been distinct and locally based: fusion cuisines, mixed martial arts, and New Age shamanism. On the other hand, there are processes of Indigenization and appropriation in which local cultures adopt and redefine foreign cultural forms. The classic examples are the cargo cults of Melanesia in which isolated Indigenous peoples “re-purposed” Western goods (cargo) within their own ritualistic practices in order to make sense of Westerners’ material wealth. Other examples include Arjun Appadurai’s (1996) discussion of how the colonial Victorian game of cricket has been taken over and absorbed as a national passion into the culture of the Indian subcontinent. Similarly, Chinese “duplitecture” reconstructs famous European and North American buildings, or in the case of Hallstatt, Austria, entire villages, in Chinese housing developments (Bosker, 2013). As cultural diasporas or emigrant communities begin to introduce their cultural traditions to new homelands and absorb the cultural traditions they find there, opportunities for new and unpredictable forms of hybrid culture emerge.

Making Connections: Big Picture

Is There a Canadian Identity?

The 2014 purchase of the Canadian coffee and donut chain Tim Hortons by 3G Capital, the American-Brazilian consortium that owns Burger King, raised questions about Canadian identity that never seem far from the surface in discussions of Canadian culture. For example, an article by Joe Friesen (2014) in The Globe and Mail emphasized the potential loss to Canadian culture by the sale to foreign owners of a successful Canadian-owned business that is also a kind of Canadian institution. Tim Hortons’s self-promotion has always emphasized its Canadianness: from its original ownership partner, Tim Horton (1930-1974), who was a Toronto Maple Leafs defenceman, to being a kind of “anti-Starbucks,” the place where “ordinary Canadians” go. Friesen’s article reads a number of Canadian characteristics into the brand image of Tim Hortons. For example, the personality of Tim Horton himself is equated with Canadianness of the chain: “He wasn’t a flashy player, but he was strong and reliable, traits in keeping with Canadian narratives of solidity and self-effacement” (Friesen).

How do we understand Canadian culture and Canadian identity in this example? Earlier in the chapter, we described culture as a product of the socioeconomic formation. Therefore, if we ask the question of whether a specific Canadian culture or Canadian identity exists, we would begin by listing a set of distinctive Canadian cultural characteristics and then attempt to explain their distinctiveness in terms of the way the Canadian socioeconomic formation developed.

Seymour Martin Lipset (1990) famously described several characteristics that distinguished Canadians from Americans:

- Canadians are less self-reliant and more dependent on state programs than Americans to provide for everyday needs of citizens.

- Canadians are more “elitist” than Americans in the sense that they are more respectful and deferential towards authorities.

- Canadians are less individualistic and more collectivistic than Americans, especially in instances where personal liberties conflict with the collective good.

- Overall, Canadians are more conservative than Americans, and less likely to embrace a belief in progress or a forward looking, liberal outlook on political or economic issues.

Lipset’s explanation for these differences is that while both Canada and the United States retain elements from their British colonial experiences, like their language and legal systems, their founding historical events were opposite: the United States was created through violent revolution against British rule (1775-1783); whereas, Canada’s origins were counter revolutionary. Canada was settled in part by United Empire Loyalists who fled America to remain loyal to Britain, and it did not become an independent nation state until it was created by an act of the British Parliament (the British North America Act of 1867). While Lipset’s analysis is disputed, especially by those who do not see American and Canadian cultural differences as being so great (Baer et al., 1990), the logic of his analysis is to see the cultural difference between the nations as a variable dependent on their different socioeconomic formations. (Note: The idea that Canada — with its influential socialist tradition responsible for Canada’s universal health care, welfare and employment insurance, strong union movement, culture of collective responsibility, etc. — is more conservative than the United States may strike the reader as strange. Lipset’s assessment is based on uniquely American cultural definitions of conservatism and liberalism.)

In this analysis, the national characteristics that Friesen argues are embodied by Tim Hortons — modesty, unpretentiousness, politeness, respect, etc. — would be seen as qualities that emerged as a result of a uniquely Canadian historical socioeconomic development. However, how well do they actually represent Canadian culture? As we saw earlier in the chapter, one prominent aspect of contemporary Canadian cultural identity is the idea of multiculturalism. The impact of globalization on Canada has been an increased cultural diversity (see Chapter 11. Race and Ethnicity). The 2011 census noted that visible minorities made up 19.1% of the Canadian population, or almost one out of every five Canadians. In Toronto and Vancouver, almost half the population are visible minorities. In a certain way, the existence of diverse cultures in Canada undermines the notion that a unified Canadian identity exists. Canada would appear to be a fragmented nation of hyphenated identities — British-Canadians, French-Canadians, Chinese-Canadians, South Asian-Canadians, Caribbean-Canadians, Indigenous-Canadians, etc. — each with its unique cultural traditions, languages, and viewpoints. In what way are we still able to speak about a Canadian identity except insofar as it is defined by multiculturalism — essentially, many identities?

Media Attributions

- Figure 3.26 Cover of Astounding Stories magazine, June 1936: The Shadow out of Time by Howard V. Brown, via Wikimedia Commons, is in the public domain.

- Figure 3.27 Celebration Town Hall in the Walt Disney town of Celebration, Florida by trevor.patt via Flickr, is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 licence.

- Figure 3.28 Colonna Infame Skinhead by Flavia, April 2010, via Flickr, is used under a CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 licence.

- Figure 3.29 I FINALLY GOT A BIKE! by Lorena Cupcake via Flickr, is used under a CC BY 2.0 licence.

- Figure 3.30 [Portrait of Bill (Buddy) De Arango, Terry Gibbs, and Harry Biss, Club Troubadour, New York, N.Y., between 1946 and 1948] by William P. Gottlieb/Ira and Leonore S. Gershwin Fund Collection, Music Division, Library of Congress, is in the public domain.

- Figure 3.31 Beatnik paper doll by Sarah, via Flickr, is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 licence.

- Figure 3.32 Photo (a) Judson improved shoe fastening 1893 by U.S. Patent Office, via Wikimedia Commons; Photo (b) Reißverschluss offen [zipper open] by Rabensteiner via Wikimedia Commons; both in the public domain.

- Figure 3.33 Always a Line at Tim Horton’s by Caribb, via Flickr, is used under a CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 licence.