7.2 Groups

Most of us feel comfortable using the word “group” without giving it much thought. But what does it mean to be part of a group? The concept of a group is central to much of how we think about society and human interaction. As Georg Simmel (1858–1915) put it, “[s]ociety exists where a number of individuals enter into interaction” (1908/1950). Society exists in and through groups. For Simmel, society did not exist otherwise. What fascinated him was the way in which people mutually attune to one another to create relatively enduring forms. In a group, individuals behave differently than they would if they were alone. They conform, they resist, they forge alliances, they cooperate, they betray, they organize, they defer gratification, they show respect, they expect obedience, they share, they manipulate, they riot, etc. At this meso-level of interaction, being in a group changes their behaviour and also their abilities. Emile Durkheim recognized that groups generate their own particular energy — collective effervescence — that gives group members confidence and powers of action they otherwise would not have. This is one of the founding insights of sociology: the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. The group has properties over and above the properties of its individual members. It has a reality sui generis, of its own kind. But how exactly does the whole come to be greater?

Defining a Group

How can the meaning of the term group be honed more precisely for sociological purposes? The term is an amorphous one and can refer to a wide variety of gatherings, from just two people (think about a “group project” in school when you partner with another student), to a club, a regular gathering of friends, a hockey team’s fans, or a collection of people who work together or share a hobby. In short, the term refers to any collection of at least two people who interact with some frequency and who share a sense that their identity is aligned with each other as a group.

Of course, every time people gather, they do not necessarily form a group. An audience assembled to watch a street performer is a one-time random gathering. Conservative-minded people who come together to vote in an election are not necessarily a group because the members do not necessarily interact with one another with any frequency. People who exist in the same place at the same time, but who do not interact or share a sense of identity — such as a bunch of people standing in line at Starbucks — are considered an aggregate, or a crowd. People who share similar characteristics (e.g., conservative-mindedness), but are not otherwise tied to one another in any way, are considered a category.

An example of a category would be Millennials, the term given to all children born from approximately 1980 to 2000. Why are Millennials a category and not a group? Because while some of them may share a sense of identity, many do not. They do not, as a whole, interact frequently with each other.

Interestingly, people within an aggregate or category can become a group. During disasters, people in a neighbourhood (an aggregate) who did not know each other might become friendly and depend on each other at the local shelter. After the disaster ends and the people go back to simply living near each other, the feeling of cohesiveness may last since they have all shared an experience. They might remain a group, practicing emergency readiness, coordinating supplies for the next emergency, or taking turns caring for neighbours who need extra help. Similarly, there may be many groups within a single category. Consider the social category of teachers, for example. Within this category, groups may exist like teachers’ unions, teachers who coordinate to coach after-school sports, or teachers who create book clubs together.

Types of Groups

Sociologist Charles Horton Cooley (1864–1929) suggested that groups can broadly be divided into two categories: primary groups and secondary groups (Cooley, 1909/1963). According to Cooley, primary groups play the most critical role in people’s lives. The primary group is usually fairly small and is made up of individuals who generally engage face-to-face in long-term, emotionally intimate ways. This group serves emotional needs: expressive functions rather than instrumental ones. The primary group is usually made up of significant others — those individuals who have the most impact on a person’s socialization or play a formative role in shaping the life of another. The best example of a primary group is the family.

Secondary groups are larger and more impersonal. They are usually task-focused and time-limited. These groups serve an instrumental function rather than an expressive one, meaning that their role is more goal- or task-oriented than emotional. A school class or office team can be an example of a secondary group. Neither primary nor secondary groups are bound by strict definitions or set limits. In fact, people can move from one group to another. A graduate seminar, for example, can start as a secondary group focused on learning course material, but as the students work together in the seminar, they may find common interests and strong ties that transform them into a primary group that meet outside of class or after the seminar has been completed.

Peter Marsden (1987) refers to one’s group of close social contacts as a core discussion group. These are individuals with whom you can discuss important personal matters or with whom you choose to spend your free time. Christakis and Fowler (2009) found that the average North American had four close, personal contacts. However, 12% of their sample had no close personal contacts of this sort, while 5% had more than eight close personal contacts. Half of the people listed in the core discussion group were characterized as friends, as might be expected, but the other half included family members, spouses, children, colleagues, and various professional consultants. Marsden’s original research from the 1980s showed that the size of the core discussion group decreases as one ages, there was no difference in size between men and women, and those with a post-secondary degree had core discussion groups almost twice the size of those who had not completed high school.

Making Connections: Case Study

Best Friends She’s Never Met

Writer Allison Levy worked alone. While she liked the freedom and flexibility of working from home, she sometimes missed having a community of coworkers, both for the practical purpose of brainstorming and the more social “water cooler” aspect. Levy did what many do in the internet age: she found a group of other writers online through a web forum. Over time, a group of approximately 20 writers, who all wrote for a similar audience, broke off from the larger forum and started a private invitation-only forum. While writers in general represent all genders, ages, and interests, it ended up being a collection of 20- and 30-something women who comprised the new forum — they all wrote fiction for children and young adults.

At first, the writers’ forum was clearly a secondary group united by the members’ professions and work situations. As Levy explained, “On the internet, you can be present or absent as often as you want. No one is expecting you to show up.” It was a useful place to research information about different publishers, find out who had recently sold what, and track industry trends. But as time passed, Levy found it served a different purpose. Since the group shared other characteristics beyond their writing (such as age and gender), the online conversation naturally turned to matters such as childrearing, aging parents, health, and exercise. Levy found it was a sympathetic place to talk about any number of subjects, not just writing. Further, when people didn’t post for several days, others expressed concern, asking whether anyone had heard from the missing writers. It reached a point where most members would tell the group if they were traveling or needed to be offline for a while.The group continued to share. One member on the site who was going through a difficult family illness wrote, “I don’t know where I’d be without you women. It is so great to have a place to vent that I know isn’t hurting anyone.” Others shared similar sentiments.

On the other hand, Zygmunt Bauman (2004) discusses the way electronically mediated groups like this online web forum tend to be frail communities, “easy to enter and easy to abandon.” They do not substitute for the more tangible and solid “we feeling” of face to face forms of togetherness, which require commitment and risk. Virtual communities “create only an illusion of intimacy and a pretense of community. They are not valid substitutes for ‘getting your knees under the table, seeing people’s faces, and having real conversation.'” They are a version of what Bauman calls cloakroom communities, places where one can hang one’s identity like a cloak for the duration of the “show” — i.e., for the duration of one’s interest in the group’s focus and interactions — and then collect it again when it is time to move on.

So is this online writers’ forum a primary group? Most of these people have never met each other. They live in Hawaii, Australia, Minnesota, and across the world. They may never meet. Levy wrote recently to the group, saying, “Most of my ‘real-life’ friends and even my husband don’t really get the writing thing. I don’t know what I’d do without you.” Despite the distance and the lack of physical contact, the group clearly fills an expressive need. How are people’s needs for primary group intimacy altered in the age of electronic media?

In-Groups and Out-Groups

One of the ways that groups can be powerful is through inclusion, and its inverse, exclusion. Groups draw boundaries and how these boundaries are drawn is of interest to sociologists because they are purely social products.

In-groups and out-groups are subcategories of primary and secondary groups that help identify this dynamic. Primary groups consist of both in-groups and out-groups, as do secondary groups. The feeling that one belongs in an elite or select group is a heady one, while the feeling of not being allowed in, or of being in competition with a group, can be motivating in a different way. Sociologist William Sumner (1840–1910) developed the concepts of in-group and out-group to explain this phenomenon (Sumner, 1906/1959). In short, an in-group is the group that an individual feels they belong to, and believes it to be an integral part of who they are. The group provides identity to the individual. An out-group, conversely, is a group someone does not belong to, or possibly defines oneself against. Often there may be a feeling of distance, disdain or competition in relation to an out-group.

Sports teams, cliques, gangs and secret societies are examples of groups that have a tendency to organize themselves into in-groups and out-groups; people may belong to, or be an outsider to, any of these. Of interest here is that these types of group are formed on the basis of voluntary membership. People join them because they identify with, and want to be identified with, an exclusive group. They are not born into them, like families, so the group’s recognition of their membership is always to some degree unguaranteed, as is their commitment to remain in the group. Nevertheless, as a demonstration of commitment, their identity comes to be at stake in them. As the prestige of the in-group rises or falls, especially with respect to out-groups, so does the prestige of personal identity. Symbols that represent the group, (emblems, clothing, gestures, names, beliefs — i.e.,Durkheim’s “totems,” see Chapter 15. Religion), consolidate group solidarity and become a proxy of group identity itself. For the zealous insider, they are treated with great respect as almost sacred objects and defended vigorously from the disrespect of outsiders, and even from renegade insiders.

Why do in-group/out-group boundaries form? One explanation is that groups form boundaries when there is competition with other groups for scarce resources. Another is that they form to defend status, privileges and self-esteem of members by denigrating outsider groups. The Robber’s Cave Study in the 1950s provided interesting but ambiguous answers to this question (Sherif et al., 1961). In the formal published study, two groups of white, middle class, 11-year-old boys were sent to a summer camp, but kept separate for a week to bond. They named themselves the Eagles and the Rattlers, which they stenciled onto t-shirts and flags. Towards the end of the week they were able to catch glimpses of the other group but not directly interact. An antipathy began to develop in each group against the “outsiders” or “intruders.” The researchers, posing as camp counselors and staff, then introduced direct competition for scarce resources between the groups in the form of baseball games and other sports with a winner-takes-all prize of a trophy and pocket-knives. Conflict between the groups ensued with food fights, the Eagles burning the Rattlers’ flag, the Rattlers retaliating by ransacking the Eagles’ cabins, and a final fist fight, which the camp counselors intervened to prevent. In the third phase of the experiment, a common crisis was created in the form of a blocked water supply, which both groups were tasked with cooperating to resolve. The boys did manage to overcome their hostility to solve the problem but some enmity remained.

The outcome of the experiment seems to support both explanations. Competition over scarce resources created an incentive to harden group boundaries, until a common problem emerged that demanded cooperation. This is the basis of realistic conflict theory, which predicts that in group/out group antagonism will develop if there is a competition for a resource in which only one group can be the winner (i.e.,a zero-sum game) and will not diminish unless superordinate goals requiring cooperation can be established (Sherif, 1966). On the other hand, the cooperative activity that ended the experiment also provided the face to face social mixing that diminished the low esteem the boys in each group held for each other. This diminished the need to defend status, self-esteem and identity against external threats. Interestingly an earlier attempt to set up the experiment failed because the first test subjects were allowed to mix before being broken into competitive groups. Despite the researchers going to lengths to introduce conflict, the boys remained cooperative and friendly, and even began to suspect the “camp counselors” of manipulating them (Perry, 2018).

While in-group affiliations can be neutral or even positive, such as the case of a team-sport competition, the concept of in-groups and out-groups can also explain some negative human behaviour, such as white supremacist movements including the Ku Klux Klan or Proud Boys, or the bullying of gay or lesbian students. By defining others as “not like us” and inferior, in-groups can end up practicing ethnocentrism, racism, sexism, ageism, and heterosexism — manners of judging others negatively based on their culture, race, sex, age, or sexuality. Some of the starkest outcomes of this behaviour results from scapegoating. As in the biblical story in Leviticus, where a goat is laden with the sins and impurities of the community and chased away into the wilderness to die, the dominant group will displace their unfocused aggression and violence onto a subordinate group (Girard, 1977). History reveals many examples of the scapegoating of a subordinate group. An example from the last century is the way that Adolf Hitler was able to use the Jewish people as scapegoats for Germany’s social and economic problems.

Making Connections: Social Policy and Debate

Bullying and Cyberbullying: How Technology Has Changed the Game

Most people know that the old rhyme “sticks and stones may break my bones, but words will never hurt me” is inaccurate. Words can hurt, and never is that more apparent than in instances of bullying. Bullying has always existed, often reaching extreme levels of cruelty in children and young adults. People at these stages of life are especially vulnerable to others’ opinions of them, and they’re deeply invested in their peer groups.

Today, technology has ushered in a new era of this dynamic. Cyberbullying is the use of interactive media by one person to torment another, and it is on the rise. Cyberbullying can mean sending threatening texts, harassing someone in a public forum (such as Facebook), hacking someone’s account and pretending to be that person, posting embarrassing images online, and so on.

A study by the Cyberbullying Research Center found that 20% of middle-school students admitted to “seriously thinking about committing suicide” as a result of online bullying (Hinduja and Patchin, 2010). Whereas bullying face-to-face requires willingness to interact with your victim, cyberbullying allows bullies to harass others from the privacy of their homes without witnessing the damage firsthand. This form of bullying is particularly dangerous because it is widely accessible and therefore easier to accomplish.

Cyberbullying, and bullying in general, made international headlines in 2012 when a 15-year-old girl, Amanda Todd, in Port Coquitlam, B.C., committed suicide after years of bullying by a cyber-stalker who lived in the Netherlands. A month before her suicide, she posted a YouTube video in which she recounted her story. It began in grade 7 when she had been lured to reveal her breasts in a webcam photo. A year later, when she refused to give an anonymous male “a show,” the picture was circulated to her friends, family, and contacts on Facebook. She was subsequently bullied by classmates and peers despite changing schools numerous times. Statistics Canada reported that 7% of internet users aged 18 and over have been cyberbullied, most commonly (73%) by receiving threatening or aggressive emails or text messages. Nine per cent of adults who had a child at home aged 8 to 17 reported that at least one of their children had been cyberbullied. Two per cent reported that their child had been lured or sexually solicited online (Perreault, 2011).

In the aftermath of Amanda Todd’s death, most provinces enacted strict guidelines and codes of conduct obliging schools to respond to cyberbullying and encouraging students to come forward to report victimization. In 2013, the federal government proposed Bill C-13 — the Protecting Canadians from Online Crime Act — which would make it illegal to share an intimate image of a person without that person’s consent. Critics, however, note that the anti-cyberbullying provision in the bill is only a minor measure among many others that expand police powers to surveil all internet activity. Will these measures change the behaviour of would-be cyberbullies? That remains to be seen. But hopefully communities can work to protect victims before they feel they must resort to extreme measures.

Reference Groups

A reference group is a group that people compare themselves to — it provides a standard of measurement and self-evaluation. The members of a reference group become role models. In Canadian society, peer groups are common reference groups. Children, teens, and adults pay attention to what their peers wear, what music they like, what they do with their free time — and they compare themselves to what they see.

But reference groups are also often made up of people one has never met: one’s generation, one’s fellow Canadians, one’s political party, one’s mountaineering community, etc. There is a strong “imaginary community” (Anderson, 1991) component in many of these broader reference groups because, although they can inspire loyalty and even intimacy, the chances of a person meeting more than a fraction of their members are minimal.

Most people have more than one reference group, so a junior highschool boy might look not only at his classmates but also at his older brother’s friends and see a different set of norms. He might study the lives of hip hop musicians and the street “scene” of distant cities that the music describes. He might observe the skills and work ethic of his favourite athletes for yet another set of behaviours. He might even be influenced by media images of “tough guy” masculinity, even if the tough guy character is largely based on an imaginary ideal.

Often, reference groups convey competing messages. For instance, on television and in movies, young adults often have wonderful apartments, cars, and lively social lives despite not holding a job. In music videos, young women might dance and sing in a sexually aggressive way that suggests experience beyond their years. At all ages, people use reference groups guide their behaviour and define social norms. Identifying reference groups can help sociologists understand the source of the social identities by examining who people aspire to or who they want to distance themselves from.

Making Connections: Sociology in the Real World

University: A World of In-Groups, Out-Groups, and Reference Groups

For a student entering university, the sociological study of groups takes on an immediate and practical meaning. After all, when someone arrives someplace new, they look around to see how well they fit in, or stand out, in the ways they want. This is a natural response to a reference group, and on a large campus, there can be many competing groups. Say a person is a strong athlete who wants to play intramural sports, but their favourite musicians are a local punk band. They may find themselves engaged with two very different reference groups.

These reference groups can also become a person’s in-groups or out-groups. For instance, different groups on campus solicit people to join. Are there students-union sponsored clubs at the school? Is there a Club Day when the student clubs set up tables and displays? The spelunking club, the Aikido club, the square dance club, the Conservative Party club, the Green Party club, the chess club, the jazz club, the kayak club, the tightrope walkers club, the peace and disarmament club, the French club, the young women in business club — enumerable clubs will try to convince students to join them.

While most clubs are pretty casual, along with a shared interest comes many subtle cues about what sorts of people will fit in and what sorts will not. While most campus groups refrain from insulting competing groups, there is a definite sense of an in-group versus an out-group. “Them?” a member might say, “They’re all right, but they are pretty geeky.” Or, “Only really straight people join that group.” This immediate categorization into in-groups and out-groups means that students must choose carefully, since whatever group they associate with will not just define their friends during their university years — it may also define types of people with whom they will not associate and never get a chance to meet.

Large Groups

It is difficult to define exactly when a small group becomes a large group. One step might be when there are too many people to join in a simultaneous discussion. Another might be when a group joins with other groups as part of a movement that unites them. These larger groups may share a geographic space, such as Occupy Montreal or the People’s Assembly of Victoria, or they might be spread out around the globe. The larger the group, the more attention it can garner, and the more pressure members can put toward whatever goal they wish to achieve. At the same time, the larger the group becomes, the more the risk grows for division and lack of cohesion.

Tepperman (2010) describes teams, bands and gangs as groups that occupy a space in between the small intimate primary group of the family or intimate friendship circle and larger more anonymous secondary groups. They do not command the “primary allegiance” of a primary group member, like family does, but they are more like a family than like larger, impersonal instrumental secondary groups (such as schools or workplaces). As such they offer an interesting window into the social structures that emerge when groups begin to get larger but are still without formal chains of command, rules, regulations, and permanent organizations. For instance, teams, bands and gangs have a clear idea of membership (who is in and who is out), a clear concept of their focal concerns, goals and activities, and a leadership structure, albeit informal. As Tepperman puts it: “Unlike small groups, TBGs (teams, bands and gangs) have a rudimentary political structure (i.e.,leaders and followers), a rudimentary legal system (i.e.,set procedures to resolve conflicts), a rudimentary economy (i.e.,a treasury and assets), and a rudimentary culture (i.e.,a shared historical memory of great events, heroes, and villains” (Tepperman, 2010). These are, however, informal and fluid structures.

As groups get larger, they get more systematized. A system or pattern is abstracted from the ongoing, casual forms of coordination of the group and imposed back onto it as an impersonal organizational structure. Going back to Simmel’s distinction between social forms and contents, one can think of three main social forms by which the content or activity of a group might be organized on a more impersonal and permanent basis: domination, cooperation, and competition. No matter what the organization is — a hockey franchise, a workplace, or a social movement — the choice of one form of organization over the others has consequences in terms of the loyalty of members and the efficiency and effectiveness of the group in achieving its goals. In the form of domination, power is concentrated in the hands of leaders while the power of subordinates is severely restricted or constrained. In extreme versions of domination, like slavery, loyalty and efficiency are low because fear of coercion is the only motivation. In the form of cooperation on the other hand, power is distributed relatively equally and loyalty and efficiency are high because the group is based on mutual trust and high levels of commitment. In the form of competition, power is distributed unequally but there is latitude for movement based on the outcome of competition for prestige or money. Loyalty and efficiency are relatively high but only as long as the pay-offs are high.

In a Star Trek episode from the 1960s, “Patterns of Force,” the crew of the Enterprise discover that a rogue historian has gone against the Prime Directive of non-interference with local societies and reorganized a planet’s culture on the basis of Nazi Germany. In order to address the planet’s condition of chaos, he appealed to the “efficiency” of Nazism only to unleash a systematic persecution of one native group by the other. The ensuing drama in the episode reveals that the historian mistook the form of domination for efficiency. As Mr. Spock puts it at the end of the episode, how could such a noted historian make the logical error of emulating the Nazis? Captain Kirk responds by saying that the failure was in putting too much power in the hands of a dictator, to which Dr. McCoy adds that power corrupts.

In fact, as historians point out, Nazi Germany was startlingly inefficient, if only because all major decisions were filtered through Hitler himself who was notoriously unpredictable, hard to get the attention of, and lacked any form of personal routine (Kershaw, 1998). The hierarchy operated on the basis of a culture of fear in which subordinates felt unable to offer criticism or factual feedback to superiors, even when decision making was poor. The irony of the Star Trek episode is of course that the Starship Enterprise itself is organized on the formal basis of hierarchical domination. It is only the leadership style that differs.

Group Leadership

Often, larger groups require some kind of leadership. In small, primary groups, leadership tends to be informal as noted above. Most families do not take a vote on who will rule the group, nor do most groups of friends. This is not to say that de facto leaders do not emerge, but formal leadership is rare.

In a series of small group studies at Harvard in the 1950s, Robert Bales (1970) studied the group processes that emerged around solving problems in training groups (referred to as T-groups). No matter what the specific tasks were, he discovered that in all the successful groups — i.e., in the groups that were able to see their tasks through to the end without breaking up — three types of informal leader emerged: a task leader, an emotional leader, and a joker. The task leader was the person who stepped up to organize the group to solve the problem by setting goals and distributing tasks. The emotional leader was the person who helped the group resolve disagreements and frustrations when strong feelings emerged. The joker made fun and fooled around but also had the knack for releasing group tension by making jokes. These leadership roles emerged spontaneously in the small groups without planning or awareness that they were needed. They appear to simply be properties of task-oriented, face-to-face groups.

Making Connections: Case Study

Women Leaders and the Glass Ceiling

Elizabeth May, former leader of the Green Party, was voted best parliamentarian of the year in 2012, hardest-working parliamentarian in 2013 and most-knowlwdgeable parliamentarian in 2020. She stands out among the party leaders as both the only female and the only leader focused on changing leadership style. Among her proposals for changing leadership are reducing centralization and hierarchical control of party leaders, allowing MPs to vote freely, decreasing narrow political partisanship, engaging in cross-partisan collaboration, and restoring respect and decorum to House of Commons debates. The focus on a collaborative, non-conflictual approach to politics is a component of her expressive leadership style, typically associated with female leadership qualities.

However, as a female leader Elizabeth May is obliged to walk a tight line that does not generally apply to male politicians. According to political analysts, women candidates face a paradox: they must be as tough as their male opponents on issues, such as foreign or economic policy, or risk appearing weak (Weeks, 2011). However, the stereotypical expectation of women as expressive leaders is still prevalent. Consider that Hillary Clinton’s popularity surged in her 2008 campaign for the U.S. Democratic presidential nomination after she cried on the campaign trail. It was enough for the New York Times to publish an editorial, “Can Hillary Cry Her Way Back to the White House?” (Dowd, 2008). Harsh, but her approval ratings soared afterwards. In fact, many compared it to how politically likable she was in the aftermath of President Clinton’s Monica Lewinsky scandal. During the 2016 presidential campaign, Hillary Clinton’s “trustworthiness” issues, which came under scrutiny through vague but concerted partisan accusations about her private emails, were compounded by gender issues in which women leaders are required to be “likeable” in ways that men are not, “honest” according to standards that men are not expected to meet, and “able to look and sound presidential” while also being authentically “real women.” For Clinton, “appearing too stern and not smiling enough on the campaign trail” was criticized as a character flaw, whereas it was not for Bernie Saunders or Donald Trump (Dittmar, 2016).

In the case of Elizabeth May, going back as far as the 2008 election leaders debate, many pundits believed that she won by being firm in her criticism of government policy, and being both intelligent and clear in her statements. She was able to articulate the rationale behind a national carbon tax to reduce greenhouse gases, whereas then Liberal leader Stéphane Dion seemed to struggle to explain his “Green Shift” policy. “We tax the pollution, and we take the taxes off families,” she said (Foot, 2008). The idea of winning debates and defeating opponents in a hostile environment is regarded as a masculine virtue. At the same time, May is subject to criticisms that have to do with her femininity, in a way that male politicians are not subject to similar criticisms about their masculinity. Media tycoon Conrad Black called her “a frumpy, noisy, ill-favoured, half-deranged windbag” to which, May quipped, “He’s right on one point: I certainly am frumpy. I don’t have anything like Barbara Amiel’s [Black’s well-known journalist wife] sense of style. But on the whole, I figure being attacked by Conrad Black is in its own way an accolade in this country” (Allemang, 2009).

Despite the cleverness of May’s retort, the pitfalls of her situation as a female leader reflect broader issues women confront in assuming leadership roles. Whereas women have been closing the gap with men in terms of workforce participation and educational attainment over the last decades, their average income has remained at approximately 70% of men’s, and their representation in leadership roles (legislators, senior officials, and managers) has remained at 50% of men’s (i.e., men are twice as likely as women to attain leadership roles in these professions than women). In terms of the representation of women in Parliament, cabinet, and political leadership, the figures are much lower at 15% (despite the fact that several provinces have had women as premiers) (McInturff, 2013).

One concept for describing the situation facing women’s access to leadership positions is the glass ceiling. Whereas most of the explicit barriers to women’s achievement have been removed through legislative action, norms of gender equality, and affirmative action policies, women often get stuck at the level of middle management. There is a glass ceiling or invisible barrier that prevents them from achieving positions of leadership (Tannen, 1994). This is also reflected in gender inequality in income over time. Early in their careers men’s and women’s incomes are more or less equal but at mid-career, the gap increases significantly (McInturff, 2013).

Tannen argues that this barrier exists in part because of the different work styles of men and women, in particular conversational-style differences. Whereas men are very aggressive in their conversational style and their self-promotion, women are typically consensus builders who seek to avoid appearing bossy and arrogant. As a linguistic strategy of office politics, it is common for men to say “I” and claim personal credit in situations where women would be more likely to use “we” and emphasize teamwork. As it is men who are often in the positions to make promotion decisions, they interpret women’s style of communication “as showing indecisiveness, inability to assume authority, and even incompetence” (Tannen, 1994).

Because of the inherent qualities in women’s expressive leadership, which in many cases is more effective, their skills, merits, and achievements go unrecognized. In terms of political leadership, one political analyst said bluntly, “women don’t succeed in politics — or other professions — unless they act like men. The standard for running for national office remains distinctly male” (Weeks, 2011).

In formal secondary groups, leadership is usually more overt. There are often clearly outlined roles and responsibilities, with a chain of command to follow. Some secondary groups, like the army, have highly structured and clearly understood chains of command, and many lives depend on those. After all, it is argued, how well could soldiers function in a battle if they had no idea whom to listen to or if different people were calling out orders? Other secondary groups, like a workplace or a classroom, also have formal leaders, but the styles and functions of leadership can vary significantly.

In structural functionalist analysis, the leadership function refers to the role of the leader in determining how an organization determines what its goals are and how it will attain them. An instrumental leader is one who is goal-oriented and largely concerned with accomplishing set tasks. An army general or a Fortune 500 CEO would be an instrumental leader. In contrast, expressive leaders are more concerned with promoting emotional strength and health, and ensuring that people feel supported. Social and religious leaders — rabbis, priests, imams, and directors of youth homes and social service programs — are often perceived as expressive leaders. There is a longstanding stereotype that men are more instrumental leaders and women are more expressive leaders. Although gender roles have changed, even today, many women and men who exhibit the opposite-gender manner can be seen as deviants and can encounter resistance. Former U.S. Secretary of State and presidential candidate Hillary Clinton provides an example of how society reacts to a high-profile woman who is an instrumental leader. Despite the stereotype, Boatwright and Forrest (2000) have found that both men and women prefer leaders who use a combination of expressive and instrumental leadership.

In addition to these leadership functions, there are three different leadership styles. Democratic leaders encourage group participation in all decision making. The group is essentially inclusive and cooperative. These leaders work hard to build consensus before choosing a course of action and moving forward. This type of leader is particularly common, for example, in a club where the members vote on which activities or projects to pursue. These leaders can be well-liked, but there is often a challenge that the work will proceed slowly since consensus building is time-consuming. A further risk is that group members might pick sides and entrench themselves into opposing factions rather than reaching a solution. Except perhaps during times of crisis, democratic styles of leadership are most effective because they allow the best ideas of the group to come forth and create the conditions for group members to “buy in” to the chosen strategies.

In contrast, a laissez-faire leader (French for “let it/them do” or “let it be”) is hands-off, allowing group members to self-manage and make their own decisions. An example of this kind of leader might be an art teacher who opens the art cupboard, leaves materials on the shelves, and tells students to help themselves and make some art. While this style can work well under conditions of mutual trust, with highly motivated, well trained, mature participants who have clear goals and guidelines, it risks group dissolution and a lack of progress.

As the name suggests, authoritarian leaders issue orders, assigns tasks and demand compliance from subordinates. These leaders are clear instrumental leaders with a strong focus on meeting goals. Often, entrepreneurs fall into this mould, like Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg. Not surprisingly, this type of leader risks alienating the workers. There are times of crisis, however, when this style of leadership can be begrudgingly accepted.

Conformity and Groupthink

People generally like to fit in to some degree. Likewise, when they want to stand out, they want to choose how they stand out and for what reasons. For example, a woman who loves cutting-edge fashion and wants to dress in thought-provoking new styles likely wants to be noticed within a framework of high fashion. She would not want people to think she was too out of touch with reality to find sensible clothes. Conformity is the extent to which an individual complies with group norms or expectations. As noted above, people use reference groups to assess and understand how they should act, dress, and behave. Not surprisingly, young people are particularly aware of who conforms and who does not. A high school boy whose mother makes him wear ironed, button-down shirts might protest that he will look stupid — that everyone else wears T-shirts. Another high school boy might like wearing those shirts ironically as a way of standing out. Recall Georg Simmel’s analysis of the contradictory dynamics of fashion (see Chapter 3. Culture): it represents both the need to conform and the need to stand out. How much does a person enjoy being noticed? Do they consciously prefer to conform to group norms so as not to be singled out?

A number of famous experiments in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s tested the propensity of individuals to conform to authority. Stanley Milgram conducted experiments in the 1960s to determine how structures of authority rendered individuals obedient (Milgram, 1963). This was shortly after the Adolf Eichmann war crime trial in which Eichmann claimed that he was just a bureaucrat following orders when he helped to organize the Holocaust. As Hannah Arendt asked in her analysis of the trial, how were Nazis like Eichmann able “to overcome . . . the animal pity by which all normal men are affected in the presence of physical suffering”? (Arendt, 1964)

Milgram had experimental subjects administer, what they were led to believe were electric shocks to a subject when the subject gave a wrong answer to a question. Each time a wrong answer was given, the experimental subject was told to increase the intensity of the shock. The experimental subjects were told that the experiment was supposed to test the relationship between punishment and learning, but the individual receiving the shocks was an actor. As the experimental subjects increased the amount of voltage, the actor began to show distress, eventually begging to be released. When the subjects became reluctant to administer more shocks, Milgram (wearing a white lab coat to underline his authority as a scientist) assured them that the actor would be fine and that the results of the experiment would be compromised if the subject did not continue. Seventy-one per cent of the experimental subjects were willing to continue administering shocks, even beyond 285 volts, despite the actor crying out in pain, and the voltage dial labelled with warnings like “Danger: Severe shock.”

Milgram interpreted the results of the experiment as a demonstration of ordinary people’s willingness to conform to figures of authority (Milgram, 1974). Actions that may be unthinkable for people on their own can be conducted without hesitation when carried out under orders. It was not the personality traits of the subjects (a desire to be cruel, moral weakness or a conformist personality structure) but qualities of the social situation that produced the alarmingly inhuman propensity to conform to authority. In particular he noted:

-

The further away the test subject was from the victim, physically and psychically, the easier it was to be cruel.

-

The effect of physical and psychical distance from the victim was enhanced when the test subject was physically and psychically closer to the authority figure, i.e.,when the test subject and the authority figure began to form an in-group separate from the victim.

-

Sequential action (in this case, incrementally increasing the voltage of the shocks) was a main “binding factor” that locked the test subject into continuing to conform to authority. “[I]f the subject decides that giving the next shock is not permissible, then, since it is (in every case) only slightly more intense than the last one, what was the justification for administering the last shock he just gave?” (Milgram, 1974). Test subjects could not stop administering the shocks at any point without having to revisit and reject the sequence of their previous decision-making.

-

The test subjects assumed an agentic state: a condition, the opposite of autonomy, in which they see themselves as carrying out another person’s wishes or passing responsibility for the acts to another. It is easier to ignore personal responsibility for actions when an individual is just an intermediate link in a chain of actions far removed from the final consequences of the action.

-

As long as there was only a single source of undivided authority, test subjects complied with the experiment. When more than one authority figure was introduced, and they were instructed to disagree about the command, compliance of the test subjects disappeared.

Similarly, Zimbardo’s Stanford Prison experiment (see Chapter 2. Sociological Research) showed that within days of beginning the simulated prison experiment, the random sample of university students, carefully screened to exclude traits of psychological abnormality, proved themselves capable of conforming to the roles of prison guards and prisoners to an extreme degree (Haney, Banks, and Zimbardo, 1973). Even though the conditions were highly artificial, within days the guards took the initiative to expand their powers to humiliate the prisoners and the prisoners responded with acts of greater submissiveness and humiliation. Unlike Milgram’s experiment in which test subjects carried out commands from an authority, Zimbardo and his colleagues simply established the scenario by dividing test subjects into roles and defining a pattern of interaction. Responsibility for the degradation could not be passed to an external authority in a lab coat because authority for each intensification of abuse was generated by the subjects themselves.

What explained the transformation of ordinary, well adjusted university students into agents of escalating and disturbingly inhumane acts of humiliation and violence? It would appear that the social nature of the group situation itself, especially the existence of a polarized division between authorities and subordinates, enabled individuals to assume a role they otherwise would never consider. It is in situations where one group is given total, exclusive and unrestricted power over another group that acts of appalling inhumanity become possible.

Making Connections: Sociological Research

Groupthink: Conforming to Group Expectations

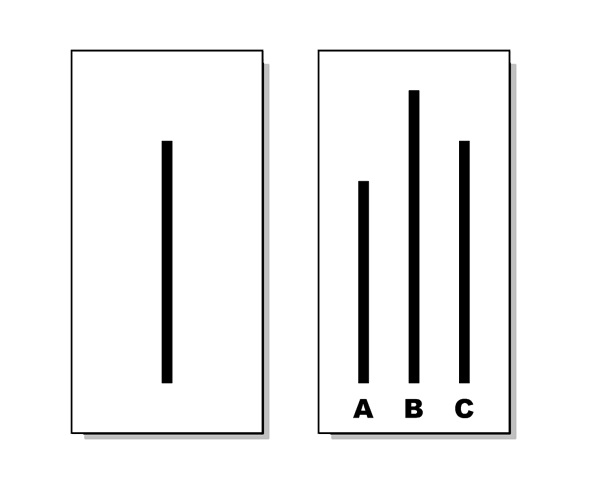

Psychologist Solomon Asch (1907–1996) conducted experiments that illustrated how great the pressure to conform is, specifically within a small group (1956). In 1951, he sat a small group of eight people around a table. Only one of the people sitting there was the true experimental subject; the rest were actors or associates of the experimenter. However, the subject was led to believe that the others were subjects brought in for an experiment in visual judgments. The group was shown two cards, the first card with a single vertical line, and the second card with three vertical lines differing in length. The experimenter polled the group, asking each participant, one at a time, which line on the second card matched up with the line on the first card.

However, this was not really a test of visual judgment. Rather, it was Asch’s study on the pressures of conformity. He was curious to see what the effect of multiple wrong answers would be on the subject, who presumably was able to tell which lines matched. In order to test this, Asch had each planted respondent answer in a specific way. The subject was seated in such a way that he had to hear almost everyone else’s answers before it was his turn. Sometimes the non-subject members would unanimously choose an answer that was clearly wrong.

So what was the conclusion? Asch found that 37 out of 50 test subjects responded with an “obviously erroneous” answer at least once. When faced by a unanimous wrong answer from the rest of the group, the subject conformed to a mean of four of the staged answers. Asch revised the study and repeated it, wherein the subject still heard the staged wrong answers, but was allowed to write down his answer rather than speak it aloud. In this version, the number of examples of conformity — giving an incorrect answer so as not to contradict the group — fell by two-thirds. He also found that group size had an impact on how much pressure the subject felt to conform. The tendency to conform was greatest in groups of 3 to 5 people.

The results showed that speaking up when only one other person gave an erroneous answer was far more common than when five or six people defended the incorrect position. Finally, Asch discovered that people were far more likely to give the correct answer in the face of near-unanimous consent if they had a single ally. If even one person in the group also dissented, the subject conformed only a quarter as often. Clearly, it was easier to be a minority of two than a minority of one.

Asch concluded that there are two main causes for conformity: people want to be liked by the group or they believe the group is better informed than they are. He found his study results disturbing. To him, they revealed that intelligent, well-educated people would, with very little coaxing, go along with an untruth. This phenomenon is known as groupthink, the tendency to conform to the attitudes and beliefs of the group despite individual misgivings. He believed this result highlighted real problems with the education system and values in North American society (Asch, 1956).

One might think that one would answer Asch’s tests honestly and accurately, despite having to go against the opinion of the other subjects. But as sociologists like Asch, Milgram and Zimbardo have demonstrated, what people do under conditions of social pressure is determined by the situation. One does not necessarily know in advance how one would respond under conditions of duress.

Media Attributions

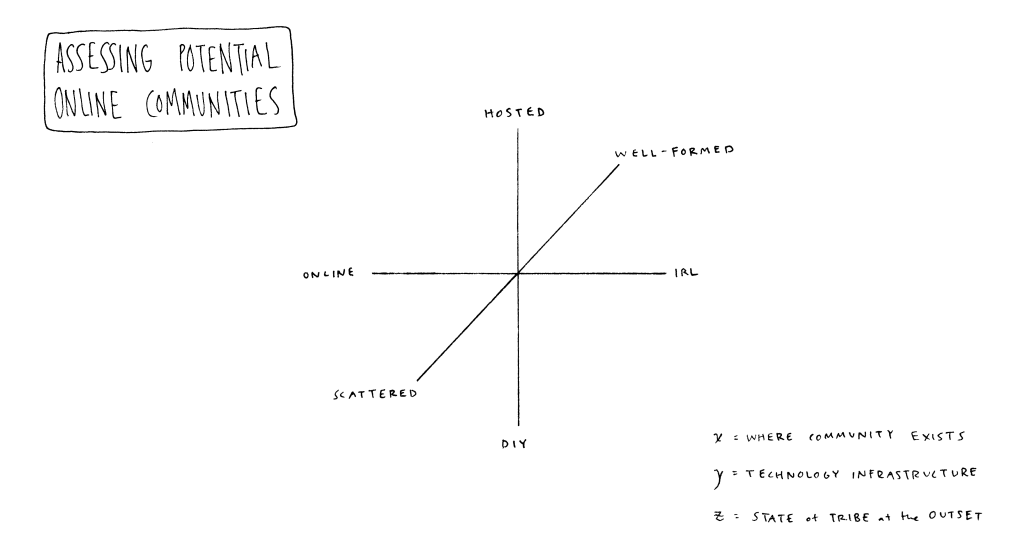

- Figure 7.7 Construction and engineering students visit the Folsom spillway job site by Michael J. Nevins/ U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, via Flickr, is in the public domain.

- Figure 7.8 Assessing Potential Online Communities by 10ch/ Beck Tench, via Flickr, is used a CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 licence.

- Figure 7.9 Mother Picks Up her Daughter’s Phone by Karolina Grabowska is is used under the Pexels site licence.

- Figure 7.10 Hayley Wickenheiser celebrates her first CIS goal with her teammates by Canada Hky is used under CC BY SA 3.0 licence.

- Figure 7.11 IMG_0022_20130224 “Aikido” by Kesara Rathnayake, via Flickr, is used under a CC BY-SA 2.0 licence.

- Figure 7.12 From the Nazi episode by Bryan Alexander is used under a CC BY 2.0 licence.

- Figure 7.13 Elizabeth May on CBC Radio One – Calgary, by Visible Hand, via Flickr, is used under a CC BY 2.0 licence.

- Figure 7.14 the hillary nutcracker by istolethetv is used under CC BY 2.0 licence.

- Figure 7.15 File:Asch experiment.png by Nyenyec, via Wikimedia Commons, is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 licence.